Discussion

We classified our participants into young children (aged 5–11 years) and an older population (≥12 years) based on vision development and frequency of vision-screening examinations at specific ages. Children tended to regularly use eye care services as part of health-screening programs for infants and children that are funded under the NHI Act, as well as a vision-screening program that was introduced by the School Health Act in South Korea. Specifically, infants and children undergo health screenings that include examinations for normal healthy growth; these include growth and development assessments and infant care consultations that reinforce health education. Before the age of 6 years, children may undergo up to seven screening examinations, i.e., at 4, 9, 18, 30, 42, 54, and 66 months. Under the School Health Act, first and fourth graders in elementary school, first year middle schoolers, and high school students are eligible for school-based vision-screening examinations at designated clinics; the examinations include tests for visual acuity, color vision, and common ocular diseases such as conjunctivitis, epiblepharon, and strabismus. In addition, school health staff check children's visual acuity in the second, third, fifth, and sixth grades of elementary school, so that all grades in elementary school, the first year in middle school, and high school students are assessed regularly. Moreover, school health staff recommend that students undergo a more thorough examination if visual acuity in either eye is less than 20 / 30.

Eye care service at ophthalmology clinics can be distinguished from pediatric clinics and optician shops or any other screening eye care services. Uncorrected visual acuity within the normal range does not guarantee that the eye is free of ophthalmologic disorders, and visual acuity cannot be fully corrected in those with amblyopia or other eye disorders. The Korean Ophthalmological Society suggests that everyone between 3 to 4 years of age should go through ophthalmologic examinations even if they do not have symptomatic ophthalmologic problems. Therefore, we also analyzed factors associated with children visiting ophthalmologists.

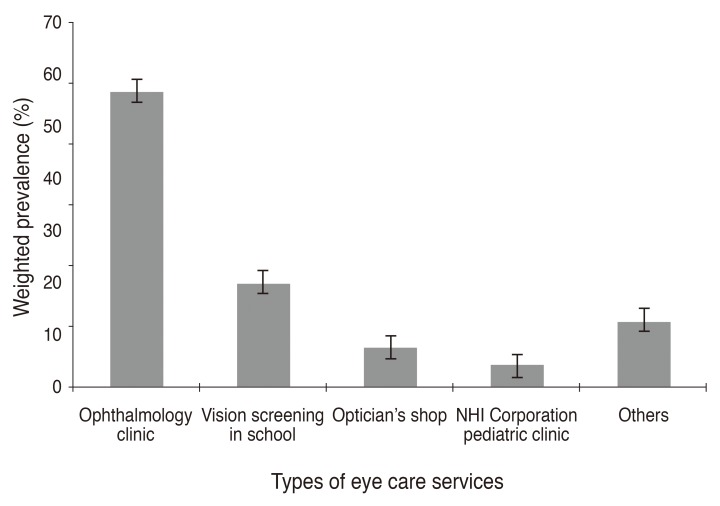

The estimated prevalence of eye care service utilization in young children during the previous year was 61.1% (95% CI, 58.1%–64.1%), which is higher than in the United States and Taiwan, where the annual rate of eye care service use was 57.4% and 43.5%, respectively, in children with ocular disease and 49.3% and 22.5% in children without ocular disease [

1322]. These differences between countries may exist because U.S. citizens do not have compulsory NHI. South Korea has a nationwide universal health system, the NHI Corporation, which is a single insurer that provides health insurance for most citizens living in the country. The NHI covers the majority of citizens, while the NBLS covers the poor and other specified groups. All South Korean citizens are compulsorily beneficiaries of either the NHI or NBLS. People who receive coverage pay a certain portion of their healthcare costs as a co-payment; this portion is determined differently depending on whether the individual is using inpatient or outpatient services, as well as the type and level of the healthcare institution. People who want coverage of services that the NHI system does not cover can get additional PHI.

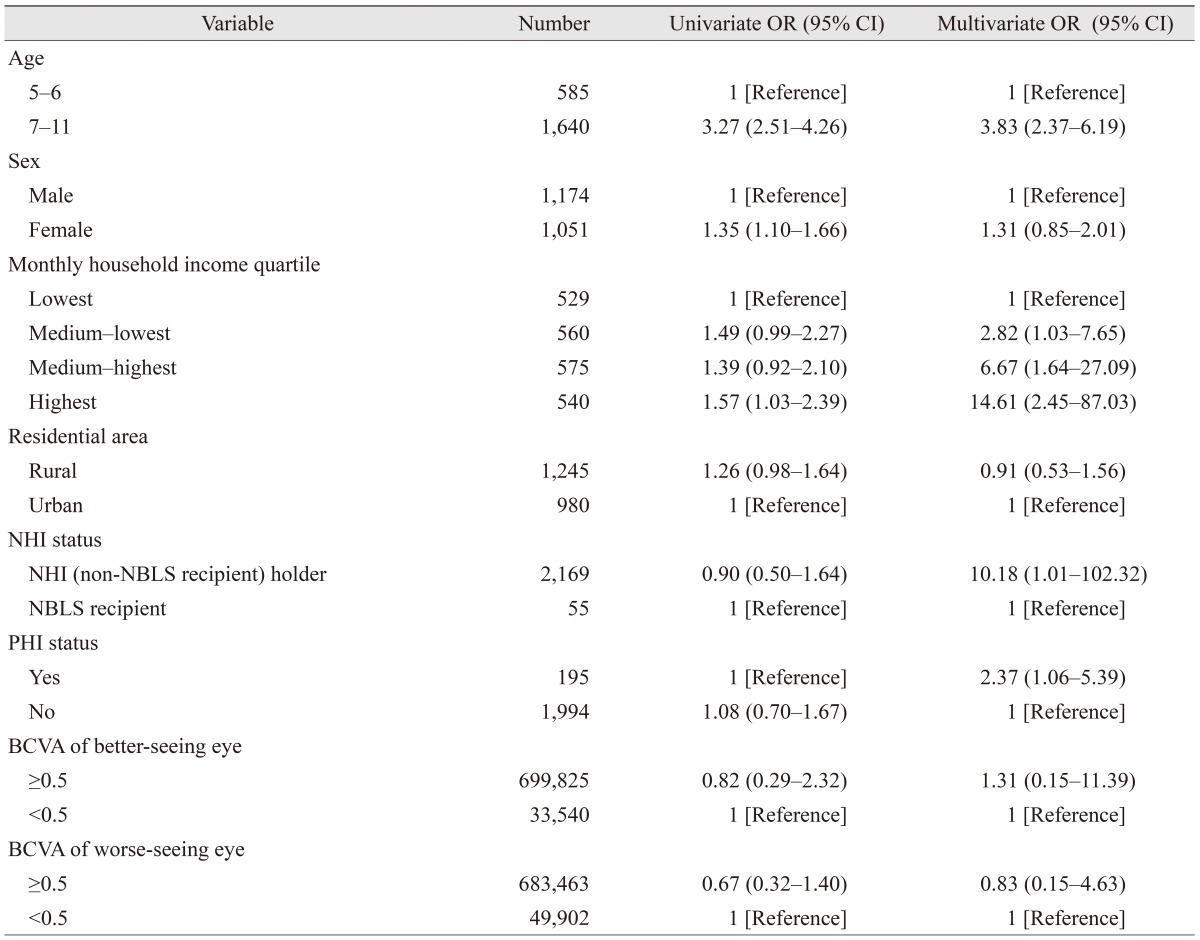

Recent research has indicated that screening leads to improved visual outcomes due to consequent early treatment in children aged 18 months to 5 years; however, in this study, the prevalence of eye care service utilization in children aged 5 to 6 years (39.4%; 95% CI, 34.0%–45.1%) was significantly lower than in those aged 7 to 11 years (68.0%; 95% CI, 64.7%–71.2%). This discrepancy by age group may have occurred because children aged 7 to 11 years can complain about the loss of vision or visual symptom compared with younger children (aged 5–6 years). However, our data indicate no association between visual acuity and the use of eye care services in young children; this discrepancy may have occurred because the school vision-screening program is compulsory, whereas the health-screening programs for children aged 5 to 6 years are not mandatory. Our results suggest that many South Koreans do not follow the recommendations to visit an eye care professional every 1 to 2 years, especially for younger children [

23]. Su et al. [

24] reported that lack of parental awareness is an important barrier to children receiving vision screening, and Williams et al. [

25] reported that family unawareness of the need for care is a major obstacle to ophthalmologic care in at-risk pediatric populations. A nationwide intervention program aimed at increasing awareness of the importance of eye care in children aged 5 to 6 years should be implemented.

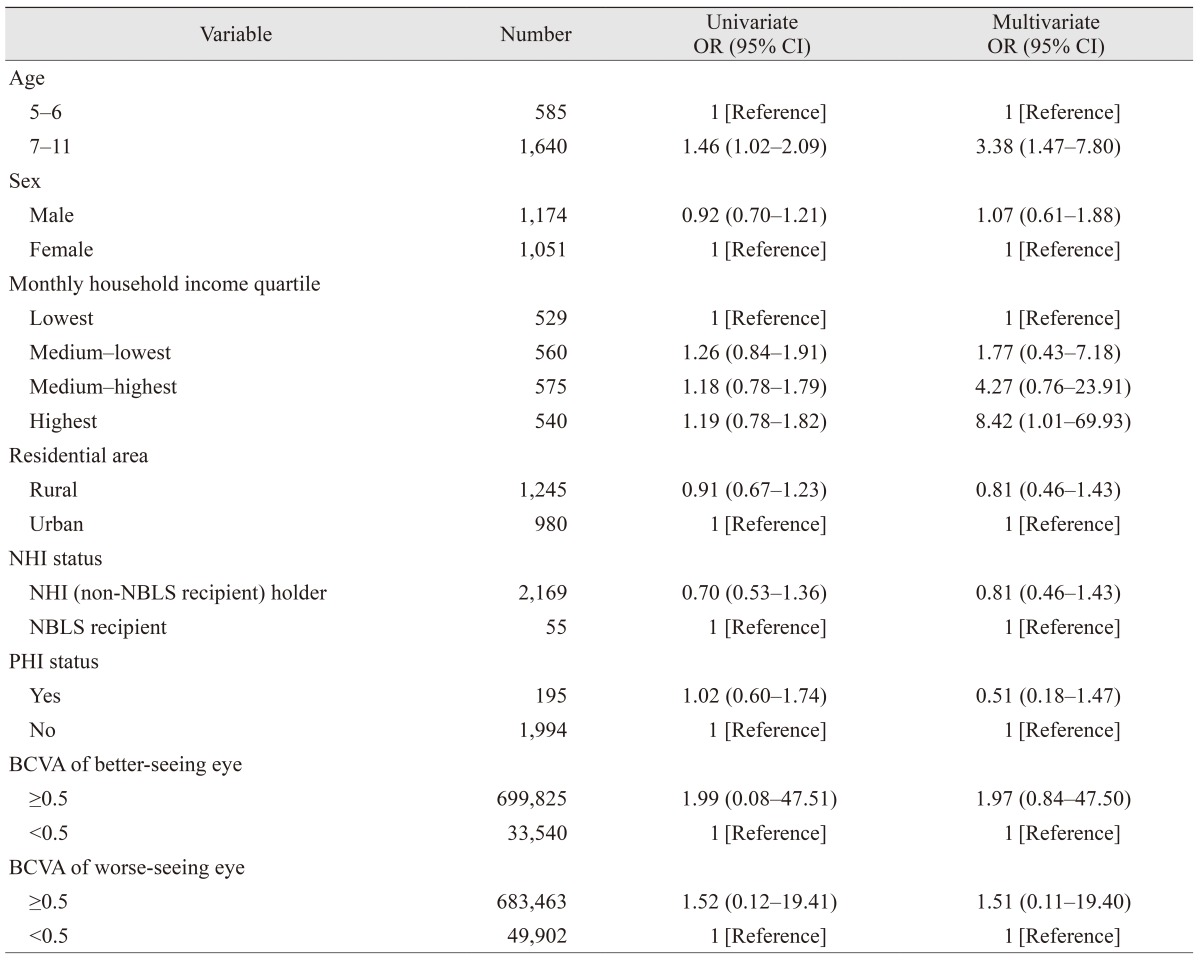

Coupled with the rapid increase in the number of health facilities in recent decades, the public health financing policy has improved access to healthcare facilities in South Korea [

26]; however, there are significant economic and insurance factors associated with eye care utilization by young children. An individual NHI holder is about 10 times more likely to have had eye care in the previous year, and those having PHI are about twice as likely to have sought eye care for young children in the past year. However, no difference in receiving eye care at ophthalmology clinic was revealed by NHI status or PHI status. Moreover, the younger children in the highest monthly household income group were more likely to have had eye care at an ophthalmology clinic in the previous year. This indicates that having national and/or PHI could lead to increased screening, but not to increased ophthalmology clinic visits. A patient might visit an ophthalmology clinic only if they were recommended for further evaluation for abnormal results in screening; additionally economic barriers might prevent care at an ophthalmology clinic, regardless of health insurance status. Since eye care for children is initiated by their caregivers, an intervention program and insurance policy should be put in place to ensure that children receive the eye care they need at the appropriate times, regardless of family income status.

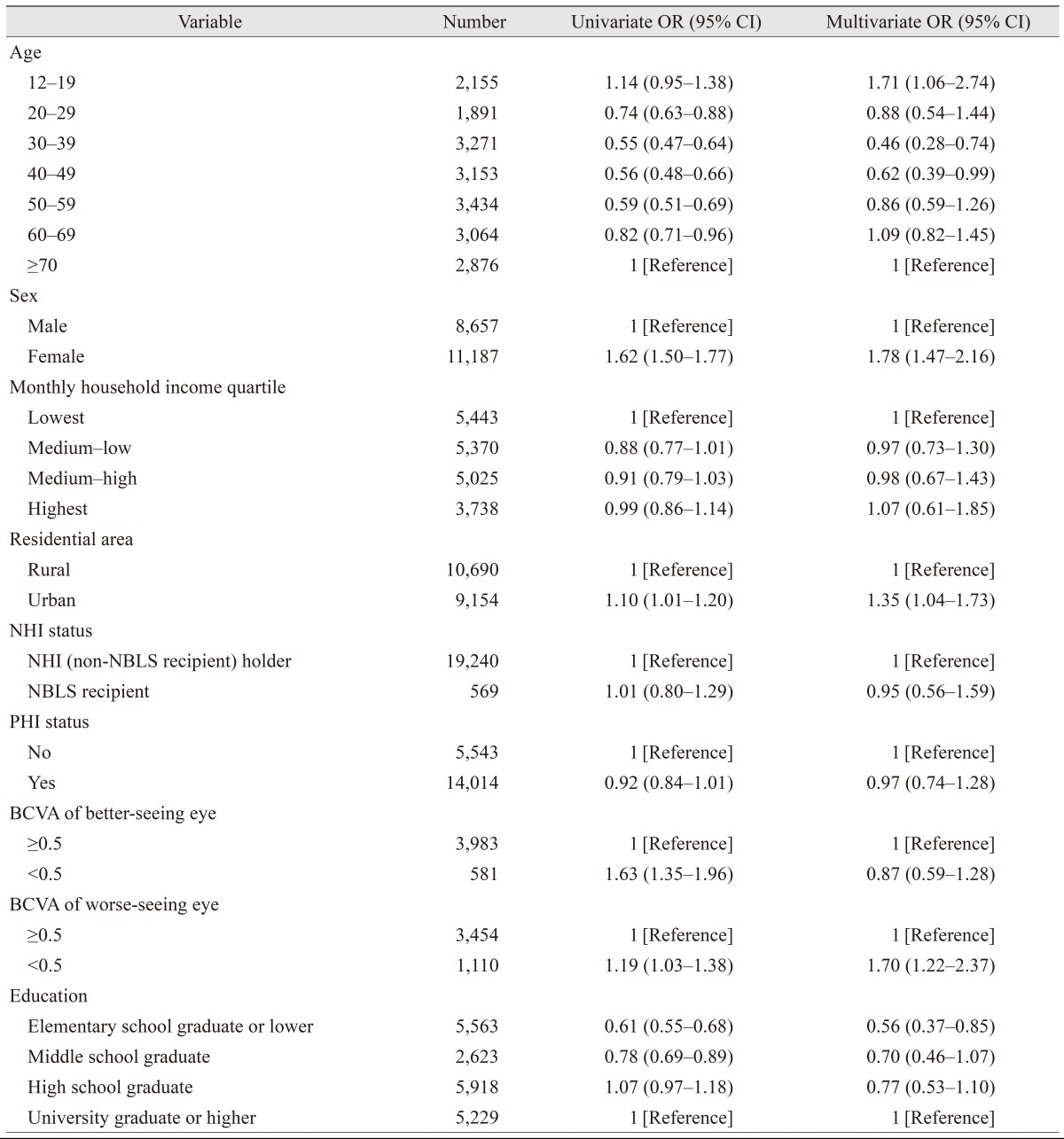

In this study, women in the older population were more likely to have attended eye care services than men; this corroborates with reports from other countries [

27282930]. For example, Lee et al. [

27] reported that women in the United States use eye care services more often than men, and this is consistent with the Beaver Dam Eye Study [

31]. In contrast, Nirmalan et al. [

32] and Emamian et al. [

33] reported that men were more likely to have received eye care services in hospitals in rural India and Northern Iran. Furthermore, a sex difference in the prevalence of visual impairment has been noted in both high-income and low-income countries [

34353637]. The main cause of this disparity is that, in low-income countries, women use eye care services much less frequently [

38]. Park et al. [

18] reported in another study that used the KNHANES Phase V survey that the prevalence of low vision and blindness was generally higher among women than men in South Korea. In the present study, the odds of eye care service utilization was higher in women than man even after adjusting the vision by BCVA ≥20 / 40 or <20 / 40 in the better-seeing eye and also in the worse-seeing eye. Additional research is required to determine whether the more frequent use of eye care services among women can be explained by their higher prevalence of low vision and blindness.

This study found that South Korea individuals in the older population with higher education levels tended to use eye care services more often than those with lower education; this is consistent with other reports [

394041]. Parental educational level is also important, because it affects not only personal use of eye care services, but also children's access to care. Several studies have shown that children with eye diseases whose parents have a lower level of education receive a lower level of eye care [

272839]. Furthermore, numerous studies have shown that the quality of physician-patient communication is lower among the less educated than among more educated patients [

27].

In our study, the aforementioned economic and insurance factors were not related to the use of eye care services in the older age population. This suggests that, in contrast with some other reports, financial constraints were not significant barriers to eye care in older individuals in our population because most are covered by the NHI system. In contrast with our study, several studies have shown that eye care is less common among uninsured adults [

27284243]. Specifically, Lee et al. [

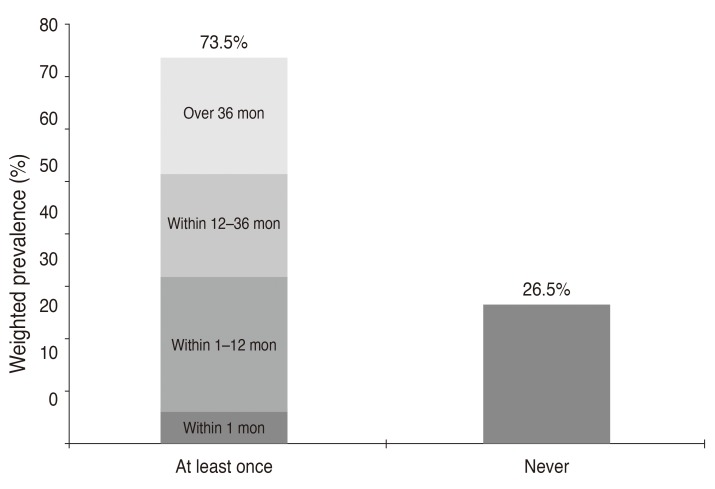

27] reported that adults who had experienced an interruption in their health insurance coverage in the previous 12 months were less likely to have reported visiting an ocular healthcare provider than those who were consistently insured. They estimated that 3.8% (7.8 million) of community-dwelling adults in the United States reported an insurance-coverage gap in the past 12 months. They also found that adults with concurrent private and public healthcare coverage were generally more likely to have reported an ocular healthcare visit in the preceding 12 months than were adults who had private insurance only, even after adjusting for sex, level of visual impairment, and education. These differences between countries may exist because U.S. citizens do not have compulsory NHI. Together, these results indicate that, while economic and insurance factors were not related to the use of eye care services in the older population of South Korea, men, rural residents, and those with better visual acuity in the worse-seeing eye were less likely to have had an eye examination during their lifetime. One possible explanation for this is that the older population may encourage their children to receive eye care, because of their economic status, but they may not have time or accessibility for their own eye care; in addition, accessing facilities may be difficult in terms of time and geographic distance, and these individuals may not prioritize eye care in the absence of serious vision impairment. Therefore, different intervention programs or campaigns are needed and should be customized for specific age groups. Education or campaigns to emphasize the importance of regular eye check-up are needed for the older South Korean population rather than encouraging them to buy PHI.

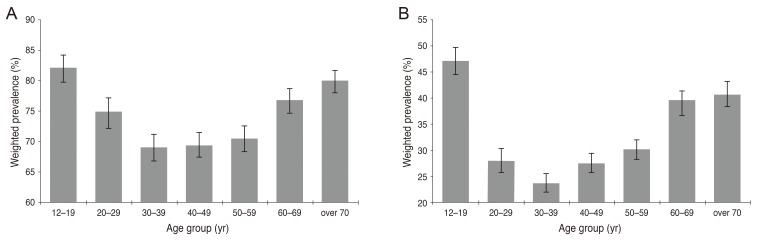

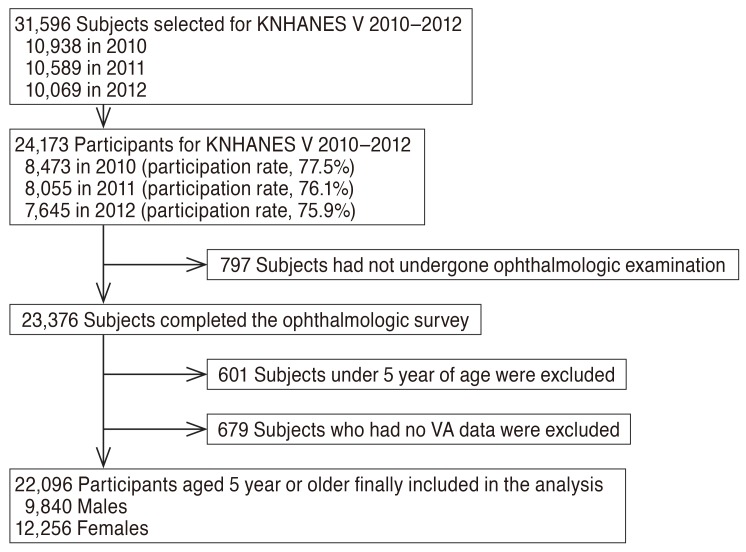

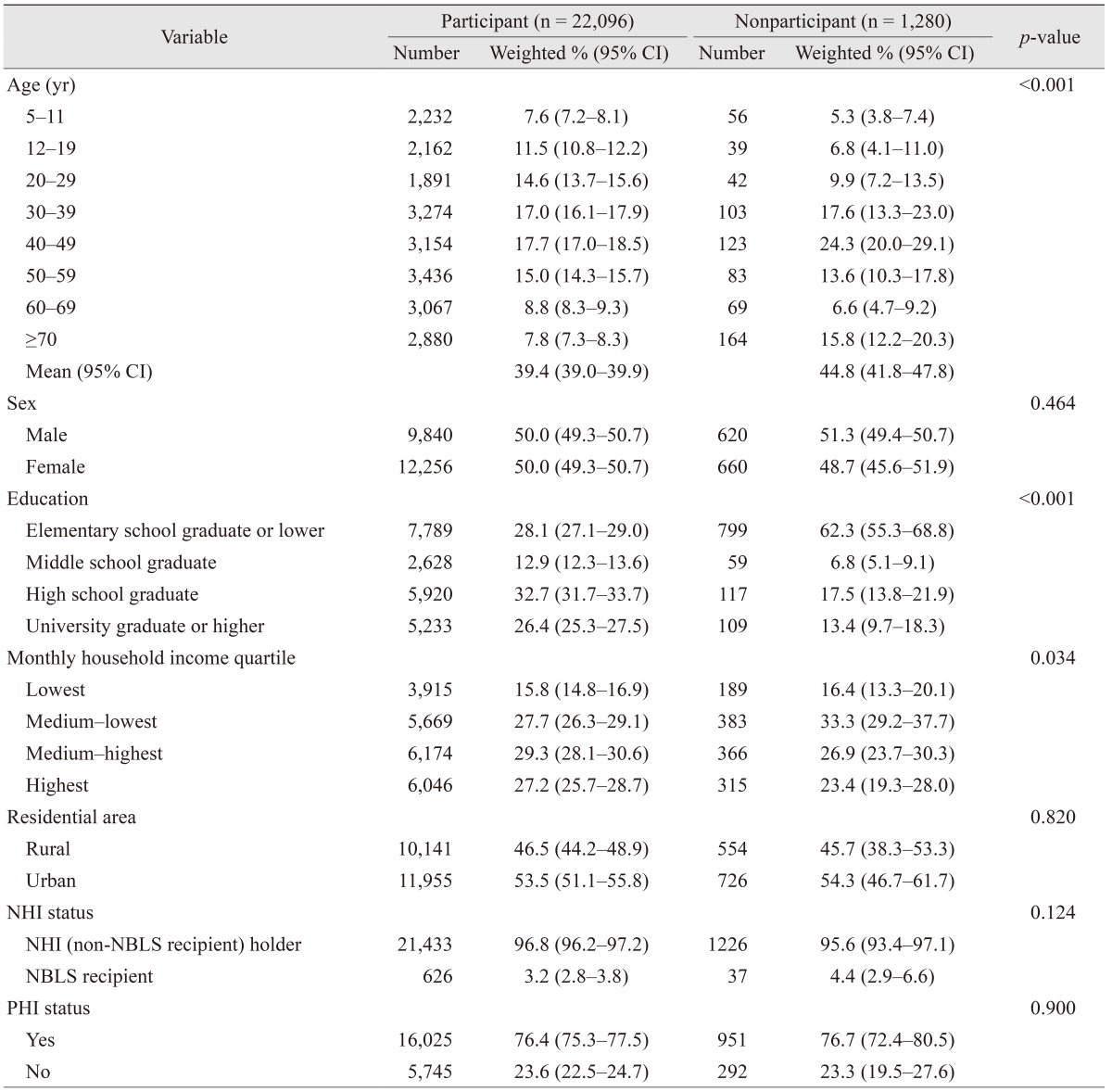

There were several limitations to our study. First, the non-response rate in the KNHANES ranged from 24.1% to 22.5% between 2010 and 2012, and non-response to the survey introduced a bias. Researchers conducting the KNHANES must devise and implement methods for reducing this bias during the KNHANES data analysis. Similarly, our data may have some degree of recall bias, and the correlations identified in this cross-sectional study do not necessarily ensure causal relationships. Second, comparison of our study participants and nonparticipants revealed significant differences: nonparticipants were more likely to be older and less educated than participants. These differences in age and education between participants and non-participants in our study may have led to an underestimation of eye care services utilization. Our results show that the elderly population (aged ≥70 years) tended to use eye care services more than younger age groups (OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.28–0.74 for age 30–39 years; OR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.39–0.99 for age 40–49 years), whereas the least educated group (elementary school or lower) tended to use eye care services less than the more highly educated population (OR, 0.56). Third, we did not compare individuals diagnosed with a specific eye condition, e.g., diabetic retinopathy or glaucoma, to those without eye disease. Individuals with diabetic retinopathy or glaucoma may be more likely to have used eye care services, because these conditions necessitate regular check-ups. To assess eye health, we analyzed the BCVA values in the better-seeing and the worse-seeing eye; however, glaucoma patients with peripheral visual field defects and central vision sparring may have good BCVA. Additional research is needed to assess whether specific eye conditions are related to the use of eye care services.

Despite the above limitations, one notable strength of this study was the large sample size (n = 22,096), which is representative of the general South Korean population in all age groups older than 5 years. Furthermore, the validity of our results was controlled; we used a standardized protocol, and our examiners were periodically trained by acting staff members of the Epidemiologic Survey Committee of the Korean Ophthalmological Society. Our findings could be used to promote the use of eye care in South Korea and to identify specific sub-groups that should receive additional education about care resources.

In conclusion, in South Korea, there are sociodemographic disparities that correlate with the use of eye care services. Our current study has demonstrated that there are significant differences in socioeconomic factors of household income, NHI status, and PHI status in children aged 5 to 11 years. Females, who are generally considered to have a more flexible work schedule, may have more time to use eye care services, as well as people who living in urban areas, where they can easily access eye care service. People that have difficulty with daily activity with a BCVA less than 20 / 40 in the worse-seeing eye are more likely to use eye care services during their lifetime; however, people with low education levels and those ≥12 years of age are not likely to use eye care service during their lifetime. Awareness must be increased to address these disparities, and targeted intervention programs must be established to increase access to eye care services. The findings of this population-based study will provide useful information for policy makers and program planners to promote the use of eye care services in South Korea.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download