Abstract

Gunshot injuries are getting more frequently reported while the civilian (nongovernmental) armament increases in the world. A 42-year-old male patient presented to emergency room of Istanbul Medipol University Hospital due to a low-velocity gunshot injury. We detected one entry point on the posterior aspect of the thigh, just superior to the popliteal groove. No exit wound was detected on his physical examination. There was swelling around the knee and range of motion was limited due to pain and swelling. Neurological and vascular examinations were intact. Following the initial assessment, the vascular examination was confirmed by doppler ultrasonography of the related extremity. There were no signs of compartment syndrome in the preoperative physical examination. A bullet was detected in the knee joint on the initial X-rays. Immediately after releasing the tourniquet, swelling of the anterolateral compartment of the leg and pulse deficiency was detected on foot in the dorsalis pedis artery. Although the arthroscopic removal of intra-articular bullets following gunshot injuries seems to have low morbidity rates, it should always be considered that the articular capsule may have been ruptured and the fluids used during the operation may leak into surrounding tissues and result in compartment syndrome.

Gunshot injuries are more frequently reported as the civilian (nongovernmental) armaments increase throughout the world.1) According to data obtained by the Small Arms Survey 2007 at the Graduate Institute in Geneva, Turkey is the 53rd country with a rate of 12.5 privately owned guns per 100 citizens.

Damage from a bullet depends on its ballistic features such as caliber, shape, and velocity. Since a temporary cavity is created by the bullet as it passes through soft tissue, unexpected neurovascular injuries and contamination may occur. Missile penetration to the knee joint without neurovascular damage or a comminuted fracture is very rare. Arthroscopic irrigation and debridement of the joint is the definitive treatment for this entity.1) Even with the excellent results of arthroscopic treatment of low-velocity gunshot wounds involving the knee joint, there may be some complications related to the injury properties and surgical technique. In this case presentation we aimed to highlight an important complication of arthroscopic removal of a bullet in the knee. We would like to report a case of leg compartment syndrome, after arthroscopic removal of a bullet in the knee joint with a noncomminuted medial femoral condyle fracture and intact neurovascular structures.

A 42-year-old male patient presented to our emergency room of Istanbul Medipol University Hospital with a low-velocity gunshot injury. We detected one entry point on the posterior aspect of the thigh, just superior to the popliteal groove. No exit wound was detected on physical examination. There was swelling around the knee and range of motion was limited due to pain and swelling. Neurological and vascular examinations revealed intact. Following the initial assessment, the vascular examination was confirmed by Doppler ultrasonography of the related extremity. There were no signs of compartment syndrome in the preoperative physical examination. A bullet was detected in the knee joint on the initial X-rays (Fig. 1). Intravenous antibiotics including cefazolin and ornidazole were started following the initial assessment.

Preoperative computed tomography (CT) scans revealed an undeformed bullet just superior to the intercondylar eminence of the tibia in coronal plane and inferior to the patella in sagittal plane (Fig. 2). A knee arthroscopy was planned and performed under general anesthesia, 4 hours after the patient's admittance. Using standard anteromedial and anterolateral arthroscopic portals, the anterior cruciate ligament, and medial and lateral menisci were found to be intact. A non-displaced flap-like osteochondral defect, approximately 1 cm × 1 cm in size, was detected on the medial femoral condyle. A midline, 1 cm long mini-incision was performed through the patellar tendon as the Swedish portal is called.2) This extra portal allows direct access to the intercondylar notch and insertion of a large-sized grasper (Fig. 3). The bullet was removed using this portal. The knee joint was debrided and irrigated with 3,000 mL of saline solution. Immediately after releasing the tourniquet, swelling of the anterolateral compartment of the leg and pulse deficiency was detected in the dorsalis pedis artery on the foot. Thus, we performed an anterior and lateral compartment release through a single lateral incision fasciotomy.

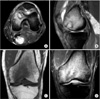

Active knee flexion exercises up to 90° were started on the first postoperative day. However, weight bearing was not allowed on the surgical side due to the chondral lesion. On the third day after surgery, the incision of fasciotomy was primarily closed. No signs of infection were detected at follow-up visits. CT and magnetic resonance ımaging was performed in the 6th postoperative week in order to evaluate the bone and chondral healing (Fig. 4). Complete union was detected at the fracture line, and the chondral lesion seemed to be healed without an additional intervention.

In the present case, we preferred immediate arthroscopic debridement and removal of the bullet rather than an open surgical approach, because of the loose appearance of the intra-articular projectile and the absence of a comminuted fracture needing repair. Although arthroscopic removal seemed to be less morbid than an open surgical approach, we encountered compartment syndrome of the leg immediately after the tourniquet release.

An open procedure for removal of intra-articular bullet fragments has disadvantages such as increased blood loss, surgical site problems and prolonged recovery time.3) However, arthroscopical removal of lead projectiles in the knee reduces the postoperative complications like synovitis, arthropathy or systemic lead toxicity by debridement and lavage of the joint with minimal surgical morbidity. 4) Additionally, intra-articular soft tissue injuries, especially including meniscal tears and free debris, would be safely and effectively treated by arthroscopic management simultaneously.5) In our patient, a small nondetached chondral lesion was observed in the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle. This lesion was healed in 6 weeks time without any further intervention.

Bullet fragments embedded in muscle or bone will frequently be encapsulated by a fibrous, avascular scar tissue, while fragments in a joint will be in subject to chemical degradation by hyaluronic acid and the pH of the synovial fluid.67) Thus, lead projectiles in joints are not considered to be physiologically inert and have to be removed when encountered.8) In addition, dissolution of the bullet by synovial fluid may yield to synovitis, lead arthropathy and increased levels of lead in the circulation. 579) Either the direct mechanical effect of the intra-articular projectile, or the destructive chemical interactions between bullet-synovial fluid and articular cartilage makes the lead fragment removal necessary.56) An immediate arthroscopic intervention was preferred in our patient, because of the mechanical joint motion restriction effect and direct contact of the bullet with the synovial fluid.

Arthroscopy is a relatively simple and less invasive procedure in the management of intra-articular knee problems. Although very rare, arthroscopic procedures may be complicated by instrument breakage or intra-articular damage,10) which would primarily result from the surgical practice of the surgeon. However, the most devastating complications are those related to neurovascular injuries and compartment syndrome. In the literature, the infrequent cases of compartment syndrome after arthroscopical interventions were mostly related to the use of mechanical infusion systems. In our patient, even though we used a manual Y-pump system, the extravasation of the fluid was associated with damage to the anterolateral knee capsule produced by the bullet at the end of its pathway. There were some reported cases of compartment syndrome caused by rupture of a Baker's cyst and a cadaveric study where extravasation was demonstrated by rupture of the knee capsule from overflow of the irrigation fluid. The rare incidence of this complication, makes it difficult to reach a consensus. In contrast to some authors who recommend waiting for spontaneous resorption of the fluid, we prefer an immediate single incision fasciotomy of the related compartment. Compartment pressure measurement is a useful diagnostic method for detecting compartment syndrome. However, in a patient like the one in our case under general anesthesia, a distended and pulseless leg following an arthroscopical intervention and a history of gunshot injury raises considerable suspicion of a compartment syndrome. That's why we preferred a minimally invasive fasciotomy and releasing of the compartment rather than compartment pressure measurement.

Although, the arthroscopic removal of intra-articular bullets in gunshot injuries seems to have low morbidity rates, there is always the possibility that the articular capsule may rupture causing the fluids used during the operation to leak into surrounding tissues resulting in compartment syndrome. In these patients, mini open surgery or dry arthroscopy may be better options.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Localization of the bullet on preoperative anteroposterior (A) and sagittal (B) oblique radiographs.

References

1. Dicpinigaitis PA, Koval KJ, Tejwani NC, Egol KA. Gunshot wounds to the extremities. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2006; 64(3-4):139–155.

2. Mulhollan JS. Swedish arthroscopic system. Orthop Clin North Am. 1982; 13(2):349–362.

3. Gupta RK, Aggarwal V. Late arthroscopic retrieval of a bullet from hip joint. Indian J Orthop. 2009; 43(4):416–419.

4. Diaz-Martin AA, Guerrero-Moyano N, Salinas-Sanchez P, Guerado-Parra E. Arthroscopic removal of an intraarticular projectile from the knee. Acta Ortop Mex. 2011; 25(4):223–226.

5. Tornetta P 3rd, Hui RC. Intraarticular findings after gunshot wounds through the knee. J Orthop Trauma. 1997; 11(6):422–424.

6. Rehman MA, Umer M, Sepah YJ, Wajid MA. Bullet-induced synovitis as a cause of secondary osteoarthritis of the hip joint: a case report and review of literature. J Med Case Rep. 2007; 1:171.

7. McQuirter JL, Rothenberg SJ, Dinkins GA, Kondrashov V, Manalo M, Todd AC. Change in blood lead concentration up to 1 year after a gunshot wound with a retained bullet. Am J Epidemiol. 2004; 159(7):683–692.

8. Sclafani SJ, Vuletin JC, Twersky J. Lead arthropathy: arthritis caused by retained intra-articular bullets. Radiology. 1985; 156(2):299–302.

9. Peh WC, Reinus WR. Lead arthropathy: a cause of delayed onset lead poisoning. Skeletal Radiol. 1995; 24(5):357–360.

10. Pierzchała A, Kusz D, Widuchowski J. Complication of arthroscopy of the knee. Wiad Lek. 2003; 56(9-10):460–467.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download