Abstract

Background

We believe that instances of neuroticism and common psychiatric disorders are higher in adults with acne vulgaris than the normal population.

Objective

Instances of acne in adults have been increasing in frequency in recent years. The aim of this study was to investigate personality traits and common psychiatric conditions in patients with adult acne vulgaris.

Methods

Patients who visited the dermatology outpatient clinic at Bozok University Medical School with a complaint of acne and who volunteered for this study were included. The Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (SCL 90-R) Global Symptom Index (GSI), somatization, depression, and anxiety subscales and the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire-Revised Short Form (EPQ-RSF) were administered to 40 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria before treatment. The results were compared with those of a control group.

Results

Of the 40 patients included in this study, 34 were female and 6 were male. The GSI and the somatization, depression, and anxiety subscales of the SCL 90-R were evaluated. Patients with adult acne had statistically significant higher scores than the control group on all of these subscales. In addition, patients with adult acne had statistically significantly higher scores on the neuroticism subscale of the EPQ-RSF.

Conclusion

Our results show that common psychiatric conditions are frequent in adult patients with acne. More importantly, neurotic personality characteristics are observed more frequently in these patients. These findings suggest that acne in adults is a disorder that has both medical and psychosomatic characteristics and requires a multi-disciplinary approach.

Acne vulgaris, which is one of the most prevalent skin disorders, is frequently seen in adolescents, but it also affects the adult population to some extent. The prevalence of acne is between 30%~85% in adolescents and young adults1. Acne is an inflammatory disease of pilosebaceus follicles on the skin of both the face and trunk2,3. Androgens may be necessary for its pathogenesis3. Acne is most frequently seen on the face as a chronic condition, and it may cause scarring of the skin and psychological disorders4. The mean age of patients with acne seen in dermatology departments during the last decade has increased from 20.5 years to 26.5 years. This may reflect an increase in the prevalence of acne in adults or an increased awareness of the disease and contemporary effective treatments5. The data on the prevalence of acne in adults is scarce6. The number of patients over 25 years of age treated for acne is increasing, and the majority of these patients are female. The prevalence of acne in adults is 3% in men5 and 11%~12% in women5,7. Acne in adults is traditionally defined as the presence of acne over age 258. There are two types of adult acne: persistent and late-onset. Acne persisting beyond 25 years of age is defined as persistent adult acne. Acne first occurring after 25 years of age is defined as late-onset adult acne. Both types are more prevalent in females9.

It has been reported that psychosomatic findings are more frequent in patients with acne and that the risk of suicide is also higher in these patients10. More severe acne has been associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression11. In addition, many patients with acne have problems with their self-image and inter-personal relationships. These persons generally experience social anxiety12 and, as a result, depression and suicidal thoughts may occur13. In this study, we investigated the incidence of both common psychiatric clinical disorders and personality characteristics in these patients.

All volunteers participating in this study were informed according to the Helsinki Declaration. Approval of the institutional ethics committee was obtained from the Bozok University Medical School Ethics Committee on Non-Interventional Clinical Investigations (IRB No. 2013/148).

The study sample consisted of 40 patients (34 women and 6 men) who visited the dermatology outpatient clinic at the Bozok University Medical School hospital between March 2013 and July 2013 and were diagnosed as having adult acne. The patients were 25~41 years in age (mean, 28.87±4.73 years). The control group consisted of 40 healthy volunteers without a known clinical disease (17 men and 23 women). The mean age of control group was 31.87±8.01 years, and the age range was 19~55 years. Exclusion criteria included the presence of comorbidities; neurological, psychiatric, and medical diseases; alcohol and/or substance abuse; and use of medications (e.g., retinoids) that may cause psychiatric diseases.

This form was developed by the authors and was used to obtain demographic data such as age, gender, educational status, and marital status.

This scale is a psychiatric screening tool that measures the level of psychiatric symptoms and negative stress reactions the person experienced and uses a self-evaluation scale. It is used in patient populations older than 17 years and who have graduated from high school. It does not have a time limitation (i.e., patients may take as long as they need to complete it), and it consists of 90 items that are assessed on a 5-point Likert scale. Each item is evaluated according the following scale: 0="None," 1="Very Little," 2="Moderate," 3="Much," and 4="Very Much." Three separate total scores may be calculated: The Global Symptom Index (GSI) is the general mean score. An increase in GSI reflects the discomfort felt by the person that is caused by the psychiatric symptoms and is the best index of this measure. It is rated with 0~4 points. The cut-off score of this psychiatric screening scale is frequently recommended as 1.0 point. There are also 9 separate subscales that assess psychiatric-disorder symptoms of 1) somatization, 2) obsessive-compulsive symptoms, 3) interpersonal sensitivity, 4) depression, 5) anxiety, 6) enmity, 7) phobic anxiety, 8) paranoid ideation, and 9) psychoticism (the checklist also includes additional subscales). Items on the subscales are also scored between 0~4 points. The Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (SCL 90-R) was developed by Derogatis (1977)14. The validity and reliability of the Turkish translation of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire-Revised Short Form was shown by Dağ15.

The Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ) is a self-assessment scale measuring the neuroticism, extraversion, and psychoticism dimensions of personality according to the personality concept developed by Eysenck. It measures the personality profiles of various psychiatric-patient groups and healthy individuals. It consists of a total of 24 items distributed across 4 subscales containing 6 items each. These are the neuroticism, extraversion, psychoticism, and lie subscales. The participant is required to respond "yes" or "no" quickly to each question. Responses of "yes" are scored as "1," and responses of "no" are scored as "0;" each subscale is rated between 0~6 points. No cut-off value was calculated, but this may be utilized in comparison studies.

The patient and control groups' demographic and clinical data were recorded on demographic data forms developed by the authors. The diagnosis of adult acne was reached by an academic dermatologist. The SCL 90-R and EPQ-Revised Short Form (RSF) were administered to every participant who fulfilled the study's inclusion criteria.

The statistical analysis was completed using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were presented as means and standard deviations. The SCL 90-R and EPQ-RSF variables for the patient and control groups were compared with the Mann-Whitney U test. Spearman correlation analysis was used to assess the relation between variables. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

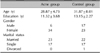

The patients' acne was located on the face for 22 patients, on the back for 6 patients, and scattered across the face, neck, back, and chest for 12 patients. Twenty-two patients had had acne since adolescence, and acne occurred after adolescence for 18 patients. The patient and control groups were similar in terms of demographic data. The mean ages of patient and control groups were 28.87±4.73 years and 31.87±8.01 years, respectively. Educational status (in years) was 11.32±3.68 for the patient group and 13.15±2.27 for the control group. Twenty-three of the patients were married and 17 were bachelors, whereas 22 members of the control group were married, 17 were bachelors, and 1 was divorced (Table 1).

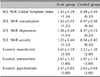

The scores from the SCL 90-R and EPQ-RSF for the patient and control groups are presented as medians and standard deviations in Table 2. The SCL 90-R GSI (Z=-6.87, p<0.001), somatization (Z=-6.43, p<0.001), depression (Z=-7.00, p<0.001), and anxiety scores (Z=-7.02, p<0.001) were significantly higher in patients with adult acne than the control group, as was the EPQ-RSF neuroticism subscale score (Z=-4.14, p<0.001). There were no significant differences between adult acne patients and the control group in terms of the extraversion (Z=-1.10, p=0.269) and psychoticism (Z=-0.41, p=0.681) EPQ-RSF subscale scores of (Table 3).

A very strong positive correlation was detected between the following SCL 90-R subscales: GSI, somatization, depression, and anxiety. In addition, there was a moderately strong positive correlation between scores on those subscales and the EPQ-RSF neuroticism subscale score in both the patient and control groups.

The primary aim of this study was to investigate common psychiatric conditions and personality characteristics in adult patients with acne. The patient and control groups were evaluated using the SCL 90-R and EPQ-RSF. This study included adult acne patients who has not previously received psychiatric treatment and had not manifested symptoms of psychiatric disorders.

Only the SCL 90-R GSI, somatization, depression and anxiety subscales were used in this study. The SCL 90-R GSI subscale scores were significantly higher in adult patients with acne than in the comparison group. This shows that psychiatric conditions are generally more frequent in adult patients with acne. The other SCL 90-R subscale scores (i.e., somatization, depression, and anxiety) were also significantly higher in adult acne patients than the comparison group. Our results are consistent with those of previous studies. Yazici et al.18 investigated anxiety, depression, and quality of life in 61 patients with acne. They used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and found significantly higher scores for both anxiety and depression. Halvorsen et al.19 investigated the association between acne severity and suicidal ideation, mental health problems, and social functioning in a study of 3,775 adolescents aged 18~19 years. Of these patients, 14% had severe acne. Approximately 1 in every 4 adolescents reported suicidal thoughts. Suicidal ideation was reported 2 times more often in females with acne than those without acne, and this likelihood increased to 3 times more often for male patients. Mental health problems were reported in a quarter of adolescents with severe acne. Although these studies are consistent with our results, we investigated adult patients with acne. Significant acne leads to psychological damage that consists of emotional distress and social anxiety, which may cause suicidal ideation20,21. Social phobia was found in 45.7% of 140 patients in another study22. In a study from New Zealand by Purvis et al.23, 64.3% of 9,567 students aged 12~18 years gave an appropriate response, 14% reported having an "acne problem," 1,294 (14.1%) reported having clinically significant symptoms of depression, and 432 (4.8%) reported anxiety symptoms. There was a positive correlation between the presence of depressive symptoms and acne severity. In another study, anxiety levels were higher in patients with acne, and there was a correlation between anxiety level and acne severity24. In a study investigating the rate body dysmorphic disorder in patients with acne, the risk increased by two times in patients given systemic isotretinoin25.

One of the most important features of our study is that none of the patients were given systemic treatment. As is well known, there are many studies showing that isotretinoin treatment induces symptoms of depression26,27. Another important aspect of our study is that our results indicate a significant increase in neuroticism, which is a primary personality trait of adult patients with acne vulgaris. Neuroticism is the most important sole predictor of common psychiatric conditions. Moreover, it also plays an important role in patients with other diagnoses that have a strong association with psychological distresses, such as low subjective well-being and physical health problems28.

In conclusion, this study shows that both common psychiatric conditions and the "neurotic" personality trait occur with considerably in high rates in patients with adult acne. This study shows that adult patients with acne are experiencing a highly psychosomatic disease. In addition, to our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate these variables in adult patients with acne.

Figures and Tables

References

3. Shaw JC. Acne: effect of hormones on pathogenesis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002; 3:571–578.

4. Dréno B. Assessing quality of life in patients with acne vulgaris: implications for treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006; 7:99–106.

5. Goulden V, Stables GI, Cunliffe WJ. Prevalence of facial acne in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999; 41:577–580.

6. Cunliffe WJ, Gould DJ. Prevalence of facial acne vulgaris in late adolescence and in adults. Br Med J. 1979; 1:1109–1110.

7. White GM. Recent findings in the epidemiologic evidence, classification, and subtypes of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998; 39:S34–S37.

8. Goulden V, Clark SM, Cunliffe WJ. Post-adolescent acne: a review of clinical features. Br J Dermatol. 1997; 136:66–70.

9. Williams C, Layton AM. Persistent acne in women : implications for the patient and for therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006; 7:281–290.

10. Lasek RJ, Chren MM. Acne vulgaris and the quality of life of adult dermatology patients. Arch Dermatol. 1998; 134:454–458.

11. Lowe JG. The stigma of acne. Br J Hosp Med. 1993; 49:809–812.

12. Magin P, Adams J, Heading G, Pond D, Smith W. The causes of acne: a qualitative study of patient perceptions of acne causation and their implications for acne care. Dermatol Nurs. 2006; 18:344–349.

13. Fried RG, Wechsler A. Psychological problems in the acne patient. Dermatol Ther. 2006; 19:237–240.

14. Derogatis LR. SCL-90: administration, scoring & procedures manual for the R(evised) version. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins Univ., School of Medicine, Clinical Psychometrics Unit;1977.

15. Dağ İ. Belirti Tarama Listesi (SCL-90-R)' nin üniversite öğrencileri için güvenilirliği ve geçerliliği. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 1991; 2:5–12.

16. Francis LJ, Brown LB, Philipchalk R. The development of an abbreviated form of the revised Eysenck personality questionnaire (EPQR-A): Its use among students in England, Canada, the U.S.A. and Australia. Pers Individ Dif. 1992; 13:443–449.

17. Karanci AN, Dirik G, Yorulmaz O. Reliability and validity studies of Turkish translation of Eysenck Personality Questionnaire Revised-Abbreviated. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2007; 18:254–261.

18. Yazici K, Baz K, Yazici AE, Köktürk A, Tot S, Demirseren D, et al. Disease-specific quality of life is associated with anxiety and depression in patients with acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004; 18:435–439.

19. Halvorsen JA, Stern RS, Dalgard F, Thoresen M, Bjertness E, Lien L. Suicidal ideation, mental health problems, and social impairment are increased in adolescents with acne: a population-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2011; 131:363–370.

20. Magin P, Adams J, Heading G, Pond D, Smith W. Psychological sequelae of acne vulgaris: results of a qualitative study. Can Fam Physician. 2006; 52:978–979.

21. Sundström A, Alfredsson L, Sjölin-Forsberg G, Gerdén B, Bergman U, Jokinen J. Association of suicide attempts with acne and treatment with isotretinoin: retrospective Swedish cohort study. BMJ. 2010; 341:c5812.

22. Bez Y, Yesilova Y, Kaya MC, Sir A. High social phobia frequency and related disability in patients with acne vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol. 2011; 21:756–760.

23. Purvis D, Robinson E, Merry S, Watson P. Acne, anxiety, depression and suicide in teenagers: a cross-sectional survey of New Zealand secondary school students. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006; 42:793–796.

24. Wu SF, Kinder BN, Trunnell TN, Fulton JE. Role of anxiety and anger in acne patients: a relationship with the severity of the disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988; 18:325–333.

25. Bowe WP, Leyden JJ, Crerand CE, Sarwer DB, Margolis DJ. Body dysmorphic disorder symptoms among patients with acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007; 57:222–230.

26. Goodfield MJ, Cox NH, Bowser A, McMillan JC, Millard LG, Simpson NB, et al. Advice on the safe introduction and continued use of isotretinoin in acne in the U.K. 2010. Br J Dermatol. 2010; 162:1172–1179.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download