Abstract

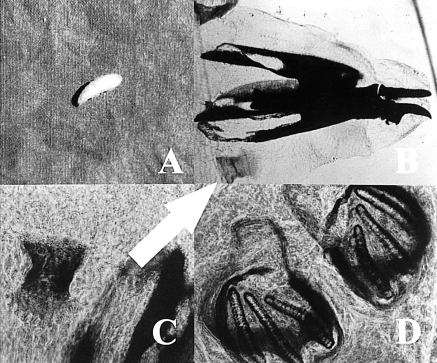

We present a case of oral myiasis in a 15-year-old boy with tuberculosis meningitis. The diagnosis was based on the visual presence of wriggling larvae about 1 cm in size and on the microscopic features of the maggots, especially those relating to stigmatic structures. The larvae were identified as third-stage larvae of Sarcophaga sp.

Go to :

Myiasis is the infestation of humans and vertebrate animals with dipterous larvae, which feed on the host's dead or living tissues, liquid body substances, or ingested food. Maggots can infest any organ or tissue accessible to fly oviposition; most cases probably occur with a female fly landing on a human host and depositing either eggs or larvae. The larvae penetrate the tissue, thus causing problems depending on the body site.1 Flies have been known to cause disease in humans in three ways: they may bite (common horsefly), live on decaying matter (maggots), or burrow into the skin (furuncular myiasis).2

Flies of the order Diptera are responsible for myiasis, the commonly implicated genera being Sarcophaga and Chlorysoma.3,4

Myiasis can be classified, depending on the condition of the involved tissue, into: accidental myiasis when larvae ingested along with food produce infection, semi-specific myiasis where the larvae are laid on necrotic tissue in wounds, and obligatory myiasis in which larvae affect undamaged skin.5 Based on the anatomic sites, affected myiasis is subdivided into cutaneous myiasis, myiasis of external orifices (aural, ocular, nasal, oral, vaginal and anal), and myiasis of internal organs (intestinal and urinary).6

Oral myiasis had been reported mainly in developing countries such as in Asia3,4,7 and very rarely in developed Western countries.8 Cases of oral myiasis have been reported in epileptic patients with lacerated lips following a seizure, in children with incompetent lips and thumb sucking habits,9 in patients with advanced periodontal disease,10 at tooth extraction sites,11 in a fungating carcinoma of buccal mucosa6 and in a patient with tetanus who had his mouth propped open to maintain his airway.12

We present a case of oral myiasis in a 15-year-old boy with tuberculosis meningitis.

Go to :

A 15-year-old boy presented in August, 2002 to Erciyes University Medical Faculty because of loss of conscious with a one month history of fever and nausea and a 5 kg weight loss. No signs or symptoms of meningeal involvement were noted. He fell down due to dizziness, lost conscious, and was admitted to the emergency service of our hospital. He was intubated and bounded to a mechanical ventilator.

Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) obtained from lumbar punctures revealed increased protein concentrations, and the results of CSF cultures were positive for M. tuberculosis. Treatment with isoniazid (300 mg daily), rifampicin (600 mg daily), streptomycin (1000 mg daily), and pyrazinamide (1500 mg daily) was started at that time.

Three maggots were discovered in the aspiration material of the oral cavity on the 27th day of hospitalization (Fig. 1-A). Examination of his oral cavity revealed poor oral hygiene. The right mandibular lymph nodes were enlarged and tender. An erythematous gingival lesion on the right side of the mandibula was found. The orifice of the lesion was treated with ether solution and one more larva leaving the lesion was collected. After complete removal of the larva, the lesion was irrigated with warm saline solution. Larvae were sent to the Veterinary Faculty of Selcuk University in 70% alcohol solution and were identified as third stage larvae of Sarcophaga sp. according to their stigmatic and cephalo-skeleton structures (Fig. 1-B, C, D).

Poor oral hygiene and a lack of awareness were considered to be the predisposing factors for larval infestation in this patient. The patient died from cardio-pulmonary arrest on the 30th day of hospitalization.

Go to :

Myiasis of the oral cavity is usually caused by flies of the order Diptera.3,4 The larvae of Diptera normally develop in decaying tissues. However, there have been reports of infestation of healthy tissue.9 Hypersalivation is suggested to be a predisposing factor.13

Factors favouring primary oral infection include halitosis, poor oral hygiene and non-closure of the mouth, as in lip incompetence and mouth breathing. 14 However, oral myiasis has also been reported in a healthy individual with acceptable oral hygiene. Oral myiasis has occurred as a nosocomial infection in immobile, injured and severely ill individuals and also as a superimposed infection in a fractured mandible.15-17 Our patient was also a severely ill and intubated patient who was bounded to the mechanical ventilator with poor oral hygiene; conditions, which combined to predispose him to oral myiasis.

In the presence of favourable conditions, the female fly deposits its eggs. After hatching, the larvae develop in the warm, moist environment, burrow into oral tissues, obtain nutrition and grow larger.18

The oral features of infection may be a painful erythematous swelling that pulsates due to movement of larvae and that may open with indurated margins present on the surface, through which the larvae may be seen.6 The larvae can also be induced to exit the lesion by application of ether solution.18 In some cases biopsy may be necessary to detect parasite sections in the submucosa.19

In our country, there have been several case reports of oral myiasis, including debilitated patients and healthy individuals.20,21 Recently reported is a gingival myiasis case report in a patient with bad oral hygiene.20 The larvae in this study were identified as Calliphoridae. Erol, et al.21 also reported a case of oral myiasis caused by larvae of Hypoderma bovis. Ciftcioglu, et al.22 reported a case of orotracheal myiasis in an 80-year-old man in coma for one week in the intensive care unit of Baskent University Hospital, Ankara, Turkey. They repeatedly recovered a number of Wohlfahrtia magnifica larvae from the mouth and from the patient's intubation tube. The patient in Ciftcioglu's study was an unconscious patient in the intensive care unit and was similar to our patient. These two cases highlight the risk of myiasis in the unconscious, debilitated patient.

In Korea, there have also been case reports about internal, oral and aural myiasis.22-24 The first reported case of internal myiasis was caused by the genus Lucilia belonging to the family Calliphoridae in 1996.23 Joo and Kim24 reported a case of nosocomial submandibular myiasis caused by Lucilia sericata. The first aural myiasis case in Korea caused by Lucilia sericata was reported in 1999 by Cho, et al.25

The diagnosis of myiasis at an early stage can prevent involvement of deeper tissues.18 This is especially important in patients with undiagnosed oral lesions, as in the case reported here. Moreover, the lack of regular oral care in these patients may cause the lesions to go unnoticed until extensive tissue involvement occurs. Precautions should also be taken in patients with habits such as mouth breathing, which may provide an ideal opportunity for the flies to lay eggs unnoticed by the patient.26

Management should be directed towards elimination of all the larvae, and this can be achieved by treating the lesion with irritating solutions such as ether.18 We accentuate the need for a careful oral examination to identify less common diseases, especially in intubated unconscious patients.

Go to :

References

1. Garcia SL, Bruckner AD. Medically Important Arthropods in Diagnostic Medical Parasitology. American society for microbiology. 1997. 3rd eds. Washington, D.C.: ASM press;p. 523–563.

2. Panu F, Gabras G, Contini C, Onnis D. Human auricular myiasis caused by Wohlfahrtia magnifica (Schiner) (Diptera :Sarcophagidae): First cases found in Sardinia. J Laryngol Otol. 2000; 114:450–453. PMID: 10962679.

3. Erfan F. Myiasis in man and animals in the old world. A Text Book for Physicians. Veterinarians and Zoologists. 1965. London: Butterworth and Co. Ltd.;p. 109.

4. Shah HA, Dayal PK. Dental myiasis. J Oral Med. 1984; 39:210–211. PMID: 6594460.

5. Gutierrez Y. Diagnostic pathology of parasitic infections with clinical correlations. 1990. Philadelphia and London: Lea and Febiger;p. 489–496.

6. Praphu SR, Praetorius F, Senagupta SK. Praphu SR, Wilson DF, Daftary DK, Johnson NW, editors. Myiasis. Oral diseases in the tropics. 1992. Oxford: Oxford University Press;p. 302.

7. Lim ST. Oral myiasis: a review. Singapore Dent J. 1974; 13:33–34. PMID: 4531736.

8. Konstantinidis AB, Zamanis D. Gingival myiasis. J Oral Med. 1987; 42:243–245.

9. Bhoyar SC, Mishra YC. Oral myiasis caused by diptera in epileptic patient. J Indian Dent Assoc. 1986; 58:535–536. PMID: 3473133.

11. Bozzo L, Lima IA. Oral myiasis caused by Sarcophagidae in an extraction wound. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992; 74:733–735. PMID: 1488228.

12. Grennan S. A case of oral myiasis. Br Dent J. 1946; 80:2–4.

13. Rawlins SC, Barnett DB. Internal human myiasis. West Indian Med J. 1983; 32:184–186. PMID: 6636724.

14. Novelli MR, Haddock A, Eveson JW. Orofacial myiasis. Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 1993; 31:36–37.

15. Minar J, Herold J, Eliskova J. Nosocomial myiasis in Central Europe. Epidemiol Mikrobiol Imunol. 1995; 44:81–83. PMID: 7670806.

16. Daniel M, Sramova H, Zalabska E. Lucilla Sericata (Diptera: Calliphoridae) causing hospital-acquired myiasis of a traumatic wound. J Hosp Infect. 1994; 28:149–152. PMID: 7844348.

17. Lata J, Kapila BK, Aggarwal P. Oral myiasis: a case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996; 25:455–456. PMID: 8986549.

18. Felices RR, Ogbureke KUE. Oral myiasis: report of a case and review of management. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996; 54:219–220. PMID: 8604075.

19. Gunbay S, Bıçakçı N. A case report of myiasis gingival. J Periodontol. 1995; 66:892–895. PMID: 8537873.

20. Gursel M, Aldemir OS, Ozgur Z, Ataoglu T. A rare case of gingival myiasis caused by diptera (Calliphoridae). J Clin Periodontol. 2002; 29:777–780. PMID: 12390576.

21. Erol B, Unlu G, Balci K, Tanrikulu R. Oral myiasis caused by hypoderma bovis larvae in a child: a case report. J Oral Sci. 2000; 42:247–249. PMID: 11269384.

22. Ciftcioglu N, Altintas K, Haberal M. A case of human orotracheal myiasis caused by Wohlfahrtia magnifica. Parasitol Res. 1997; 83:34–36. PMID: 9000230.

23. Chung PR, Jung Y, Kim KS, Cho SK, Jeong S, Ree HI. A human case of internal myiasis in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 1996; 34:151–154. PMID: 8925248.

24. Joo CY, Kim JB. Nosocomial submandibular infections with dipterous fly larvae. Korean J Parasitol. 2001; 39:255–260. PMID: 11590916.

25. Cho JH, Kim HB, Cho CS, Huh S, Ree HI. An aural myiasis case in a 54-year-old male farmer in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 1999; 37:51–53. PMID: 10188384.

26. Bhatt AP, Jayakrishnan A. Oral myiasis: a case report. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2000; 10:67–70. PMID: 11310129.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download