Abstract

This report presents a rare example of a bilateral congenital anophthalmos and an agenesis of the optic pathways. The MR imaging studies revealed that the eyeballs, optic nerves, optic chiasm, optic tracts and optic radiation were absent. The chromosomal examination was normal. Mild mental retardation was also observed. Apart from the rarity of the anophthalmos and the total absence of the optic pathways, no etiologic reason for this pathology could be detected, which makes this case more significant.

A maldevelopment of forebrain structures is known to be a result of insults occurring during the first few weeks of gestation. Anophthalmos, which is an absence of the eye, is an example of this maldevelopment that can also be found with associated intracranial anomalies, namely the absences of the optic nerves, optic chiasm, optic tracts, optic radiations and anomalous corpus callosum. The insults that cause this maldevelopment can be summarized as trauma,1 congenital infections,2 heredity3-5 and several syndromes.2,5 Here we present a case of congenital anophthalmos and agenesis of the optic pathways with no convincing etiologic reason.

The patient is a 24-year old female who had bilateral congenital anophthalmos. Her family has three girls and the patient is the oldest. She was born after an uneventful pregnancy. Her parents were healthy and showed no consanguinity.

The ophthalmologic examination after birth showed an absence of the eyeballs. She was accepted as an isolated congenital anophthalmos case. Since then, she has had no radiological examinations, especially a CT or an MRI procedure, which would have allowed the pathologies to be observed within the brain.

The family history was unremarkable. The chromosomal examination was normal. The other two sisters of the family were completely normal.

In the current ophthalmologic examination after 24 years, the patient had hypoplastic orbits and well formed but rudimentary eyelids and brows. She had a bilateral anophthalmos.

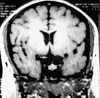

MR imaging studies revealed that the eye bulbs were absent and replaced by residual soft tissue (5 mm in diameter) which was isointense with muscle in the T1-weighted sequences (Fig. 1 and 2). The extraocular muscles were inserted to the residual bulb and were medially displaced (Fig. 1). The optic nerves, the optic chiasm, the optic tracts and the optic radiations were all absent (Fig. 1-4). The lateral ventricles were enlarged on both sides (Fig. 2). The corpus callosum was present and was slightly diminished in size (Fig. 3).

The patient also had mild mental retardation.

Eye development is first evident at the beginning of the fourth week.6 The optic grooves appear in the neural folds at the cranial end of the embryo. As the neural folds fuse to form the forebrain, the optic grooves evaginate to form the optic vesicles, which project from the wall of the forebrain into the adjacent mesenchyme. As the optic vesicles grow, their distal ends expand and their connections with the forebrain constrict to form optic stalks, which are the precursors of the optic nerves. The optic nerve is formed by more than a million nerve fibers that grow into the brain proceeding centrally to decussate through the primitive chiasmal commissura. A deficiency in the proper formation of the connections between the globes and the optic pathways results in hypoplasia or an absence of related white matter tracts.4

An interruption of embryogenesis within the first few weeks of gestation is the main cause of the primary form of congenital anophthalmos, which encompasses the aplasia of the eyeballs and the absence of the optic pathway. Various factors have been reported to be the cause of this extremely rare anomaly. Among those trauma,1 congenital infections,2 heredity,3,7 and several syndromes2,4,5 have been reported. Anomalous corpus callosum,2,8 neurocutaneous disorders (incontinentia pigmenti) and, particularly in unilateral ones, some craniofacial syndromes may accompany the congenital anophthalmos. However, a case of a total absence of the optic pathways was also reported without any accompanying pathology.9

Diagnostic amniocentesis has been reported to be a factor responsible for the congenital anophthalmos without the absence of optic pathways.1 In our case, there is no possibility that the anophthalmos resulted from a diagnostic amniocentesis.

Congenital infections, such as toxoplasmosis and rubella, may be a factor in congenital anophthalmos.2,10 However, there was no history of such infections in our case.

Heredity has been showed to be a cause of anophthalmos.1,3,7 Most anophthalmos cases are sporadic and probably have a multifactorial etiology. Nevertheless, some authors have reported an autosomal or X-linked recessive inheritance. Brunquell, et al. reported a case of an X-linked anophthalmos.3 The patient was a 27-year-old man with severe developmental defects and accompanying pathologies such as seizures, small head, clubbed feet, and locomotor deficiencies. He also had a maternal male cousin with unilateral anophthalmos and contralateral microphthalmia. On the other hand, Sensi et al. reported a family with congenital anophthalmos with a dominant pattern of inheritance.7 Two children of the family were affected with anophthalmos, of whom only one was bilateral. That case differed from the others by an absence of accompanying anomalies as mental retardation, congenital malformations and other ocular anomalies. Our case did not have any congenital malformations except for mild mental retardation but had a total absence of the optic pathway. In addition, the family history showed that there was no other member with anophthalmos.

Anophthalmos may accompany several syndromes.2,4,5 Marcus, et al.4 reported an anophthalmos case with focal dermal hypoplasia. Although the primary feature of this disorder is an undeveloped dermal connective tissue, additional congenital defects of the eye, skeleton and soft tissues are common. None of the features of our case is related to any of these symptoms.

Albernaz, et al. reported the most similar case to ours.2 In their article, they demonstrated 8 children with congenital anophthalmos of whom only 3 had bilateral anophthalmos. Among those three, two had a thinner corpus callosum and the third one had none. Our case differs from the case reported by Albernaz in that she had a normal corpus callosum.

Scott, et al. reported a similar case of congenital microphthalmos and aplasia of the optic nerves, chiasm and tracts in an otherwise healthy subject.9 No etiologic factor was given in this article. The difference in our case was that the patient has an anophthalmos instead of microphthalmos.

An individual developmental anomaly of the orbits, optic nerves and chiasm may be encountered in otherwise healthy subjects. In a recent article, Pearce described a case of the aplasia of the optic chiasm with a unifocal polymicrogyria.11 Patients with polymicrogyria have also epilepsy, mental development delays and focal neurological symptoms. The MR images of our case did not detect any polymicrogyria. No epilepsy and focal neurological symptoms were encountered either. Only mild mental retardation was found in our case.

None of the above-mentioned factors (trauma, heredity, congenital infections, syndromes, neurocutaneous disorders), which could explain the total absence of visual pathways, was identified in our case. The present case is not only a congenital bilateral anophthalmos case but also has a total absence of the optic pathway without any etiologic factors. In contrast to previous reports, there are no accompanying anomalies except for the mild mental retardation.

Figures and Tables

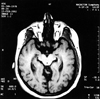

Fig. 1

Axial T1-weighted MR image shows bilateral fibrotic eye bulbs in both orbits (arrow). The rudimental medial and lateral recti are medially displaced (arrow head). Minimal enlargement of the lateral ventricles but no hypotense signal changes of the optic radiation can be observed.

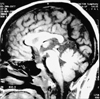

Fig. 2

Inversion recovery sequence shows the enlarged ventricles and an absence of the optic radiations (arrow).

References

1. BenEzra D, Sela M, Peer J. Bilateral anophthalmia and unilateral microphthalmia in two siblings. Ophthalmologica. 1989. 198:140–144.

2. Albernaz SA, Castillo M, Hudgins PA, Mukherji SK. Imaging findings in patients with clinical anophthalmos. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997. 18:112–113.

3. Brunquell PJ, Papale JH, Horton JC, Williams RS, Zgrabik MJ, Albert DM, et al. Sex-linked hereditary bilateral anophthalmos. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984. 102:108–113.

4. Marcus DM, Shore JW, Albert DM. Anophthalmia in the focal dermal hypoplasia syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990. 108:96–100.

5. Sener RN. Cranial MR imaging findings in Waardenburg syndrome: anophthalmia, and hypothalamic hamartoma. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 1998. 22:409–411.

6. Moore KL, Persaud TVN. The developing human. 1998. 6th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company.

7. Sensi A, Incorvaia C, Sebastiani A, Calzolari E. Clinical anophthalmos in a family. Clin Genet. 1987. 32:156–159.

8. Daxecker F, Felber S. Magnetic resonance imaging features of congenital anophthalmia. Ophthalmologica. 1993. 206:139–142.

9. Scott IU, Warman R, Altman N. Bilateral aplasia of the optic nerves, chiasm, and tracts in an otherwise healthy infant. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997. 124:409–410.

10. Waheed K, Jan W, Calver DM. Aplasia of the optic chiasm and tracts with unifocal polymicrogyria in an otherwise healthy infant. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2002. 39:187–189.

11. Pearce WG, Nigam S, Rootman J. Primary anophthalmos. Histological and genetic features. Can J Ophthalmol. 1974. 9:141–145.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download