Abstract

Purpose

The incidence of thyroid cancer is relatively high, especially in young women, and postoperative scarring after thyroidectomy is an important problem for both patients and clinicians. Currently, there is no available product that can be used for wound protection during thyroid surgery. We used the EASY-EYE_C, a new silicone-based wound protector.

Methods

We conducted a double-blind randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy of the EASY-EYE_C with surgical scars. We studied 66 patients who underwent conventional total thyroidectomy or hemithyroidectomy performed by a single surgeon from August 2015 to June 2016. At 6-week follow-up, a single blinded physician observed the wounds to make clinical assessments using the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS), the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS), and a modified Stony Brook Scar Evaluation Scale (SBSES).

Results

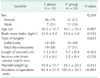

There were no significant differences by sex, age, type of surgery, body mass index, length of wound, incision site (from sternal notch), or thyroid weight, but the duration of operation was significantly shorter in the experimental group (E group). The e-group also had better POSAS scores than the control group (C group), with means of 43.2 (standard deviation [SD], ±15.9) versus 68.3 (SD, ±21.5), respectively (P < 0.05). The modified SBSES and VSS scores were similar to those from the POSAS.

Thyroid cancer prognosis is very good, and the frequency of complications after surgery is very low. Therefore, the cosmetic aspects of the surgery scar are now being emphasized [1]; a large number of thyroid cancer patients are very interested in the cosmetic aspects of their scars [2], partly because thyroid cancer has a relatively high incidence in young women and partly because a conventional thyroid surgery scar is highly visible. Therefore, in order to improve the aesthetics of these scars, minimally invasive thyroid surgery, including robot-assisted and endoscopic surgery, has been attempted and continues to develop [3456]. A recent study reports that it is possible to reduce the incision size during surgery to minimize the size of the scar and found high patient satisfaction with the cosmetic effects [7]. However, small incisions could be damaged by excessive traction force or high temperatures from the energy delivery device because of the narrower surgical field. Thus, the risk of postoperative edema, burn, and scarring is increased [8]. When a surgical assistant enforces traction with the retractor to increase visibility in the surgical field, applying excessive force to the incision site could cause inflammation of the skin due to edema or blood circulation disorders, which could cause the postsurgical scarring.

A wound protector made of silicone has already been demonstrated to significantly prevent the drying of the surgical wound and to reduce the incidence of infection [9], and it has been widely used during endoscopic (laparoscopic, thoracoscopic) surgery. However, there is no available product that can be used during thyroid surgery. To address this lack, one study introduced covering the wound site with surgical gloves to protect the incision, and another used a drain made of silicone as a wound protector [1011]. However, these methods are not widely used because of discomfort in use or the question of cosmetic effects. For this study, we used the EASY-EYE_C, a new silicone-based wound protector, to keep the wound from drying out and to protect against contamination from the tumor cells of the extracted organ as well as to add a self-retaining retraction function. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of the EASY-EYE_C in protecting wounds from excessive traction, infection, and injuries from high temperatures and ultimately to improve the cosmetic aspects of the wounds. To objectively evaluate the scars, we used the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS), Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS), and modified Stony Brook Scar Evaluation Scale (SBSES), which were recently used in a number of papers [121314].

We conducted this study as a double-blind randomized trial with an allocation ratio of 1:1. Informed consent was obtained from patients on the day before surgery. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, The Sungkyunkwan University of Korea, on August 20, 2015 (approval number: KBSMC 2015-07-011-002).

We investigated a consecutive series of patients who underwent conventional total thyroidectomy or hemithyroidectomy performed by a single surgeon from August 2015 to June 2016. The exclusion criteria were previous surgery in the neck, known allergies to chemical products, history of hypertrophic scars or keloids, or poor Korean language skill, which would have prevented patients from clearly understanding and responding to the questions on the POSAS.

The same surgeon performed each operation through open cervical incisions between 4.5 and 6 cm (mean ± standard deviation [SD], 5.2 ± 0.34) long. The skin was incised with a scalpel (15 blades) down to the subcutaneous tissue and then with electrocautery until the subplatysmal plan, where the skin flaps were dissected up to the cricoid superiorly and the sternal notch inferiorly, with careful hemostasis. Then, the surgeon applied the EASY-EYE_C in the experimental group (E group) until the thyroidectomy was complete but not in the control group (C group) (Fig. 1). The surgeon performed each thyroidectomy in the usual way using retractors and monopolar and ultrasonic electrocautery and removing the EASY-EYE_C after each surgical specimen was extracted. The surgeon achieved meticulous hemostasis before approximating and closing the skin layers; after he reapproximated the strap muscles of the neck and closed the deep subcutaneous layer with an interrupted absorbable suture, he used an intradermal continuous suture with 5-0 maxon on the skin. After each operation, the patients received a standard postoperative protocol and analgesic regime.

This EASY-EYE_C device consists of a silicone-based protector that covers the skin at the incision site and a plastic part that covers the entire protector. On the plastic cover, there are eight parts that can be hooked in eight directions and 2 types of hooks, all of which can be adjusted depending on the surgeon's needs during the surgery; once the hook is applied, the surgeon can expand the wound from 3 to 8 cm and adjust the width by 2 mm (Fig. 2).

At 6-week follow-up, a single blinded physician observed the wounds to make objective clinical assessments in person. The primary end point was the appearance of the wound at the sixth postoperative week as determined by the POSAS score [15]; the POSAS was initially developed for burn scars, but it has been used and validated for multiple types of wounds [161718]. It is composed of two subscales, the Observer Scale (OSAS) and the Patient Scale (PSAS). The OSAS score comprises seven domains, all graded on a 10-point scale, with 1 indicating normal skin and 10 indicating the worst scar imaginable; a summary score of 7 indicates normal skin, with 70 being the worst possible scar result. After scoring the domains, the observer then rates the overall scar appearance on a visual analogue scale that corresponds to a 10-point scale. The PSAS has seven domains, all graded by the patient on a 10-point scale; 1 indicates the best or most normal result, and 10 indicates the worst or most disfiguring result. A summary score of 7 corresponds to normal skin, and 70 is the worst scar imaginable to the patient (Table 1). The OSAS was completed by a single observer who was trained in the use of the instrument on a series of patients before the start of the study, and the patients completed the PSAS during the same follow-up visit (Fig. 3).

We assessed secondary outcomes including the VSS summary score and the modified SBSBE score along with the primary end point. The VSS (also known as the Burn Scar Index) was created in 1990 and is the most widely used rating scale for scars [19]. Four physical characteristics are scored: height, pliability, vascularity, and pigmentation, and each variable consists of ranked subscales that are summed to obtain a total score ranging from 0 to 13, with 0 representing normal skin (Table 2).

The modified SBSES includes width (0, scar widening prominent and >2 mm; 1, scar widening present and ≤ 2 mm; 2, no scar widening), height (0, prominent scar elevation; 1, scar elevation present; 2, no scar elevation), color (redness) (0, scar prominently redder than the surrounding; 1, scar redder than the surrounding; 2, scar of the same color as or lighter than the surrounding skin), and visibility of the incision line (0, prominent incision line; 1, incision line present; 2, incision line absent) (Table 3).

We determined the sample size considering the expected OSAS scores, which were our primary end point for this study. Based on previous literature, for means of 13.3 (SD, ±4.4) in the E group and 10.2 (SD, ±3.8) in the C group, a power of 80%, and an expected confidence interval (CI) of 95% (corresponding to P < 0.05), the computed sample size consisted of 2 groups of 30 patients each. After we added 10% to account for the risk of dropouts, we enrolled a total of 33 patients in each group.

We analyzed the data using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 24.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA): we compared the mean scores for each group with the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Student t-test for continuous variables. We also tested for correlations using Pearson correlation coefficient

During the study period, 66 patients underwent thyroidectomy, and all agreed to be enrolled in the study. There were no significant differences by sex, age, type of surgery, body mass index (BMI), length of wound, incision site (from the sternal notch), or thyroid weight, but operation duration was significantly shorter in the E group; these findings are summarized in Table 4. Of the 33 patients in the E group, 2 had benign follicular adenoma, 2 had nodular hyperplasia, 2 had Grave disease, and 27 had papillary carcinoma. Of the 33 patients in the C group, 1 had benign follicular adenoma, 3 had Grave disease, and 29 had papillary carcinoma. No recurrent laryngeal nerve injury or wound infection was noted in either group.

For POSAS scores, those in the E group were more favorable, with a mean of 43.2 (SD, ±15.9) compared with 68.3 (SD, ±21.5) in the C group, and this difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05); Fig. 4 shows the distribution of scores for the different items. By mean observer and patient assessment, the E group showed significantly better outcomes in most of the scale subdomains. Separately, the mean differences in the modified SBSES subdomain scores between the E group and the C group were significant for all four subdomains: width (P = 0.013; 95% CI, –0.65 to –0.08), height (P = 0.011; 95% CI, –0.80 to –1.11), color (P = 0.007; 95% CI, –078 to –0.13), and incision line (P = 0.012; 95% CI, –0.64 to –0.08). The E group also showed significantly better VSS scores; only the pigmentation subdomain was not significant: pigmentation (P = 0.314; 95% CI, –0.21 to 0.63), vascularity (P = 0.023; 95% CI, 0.05 to 0.73), pliability (P < 0.001; 95% CI, 0.33 to 1.12), and height (P = 0.016; 95% CI, 0.07 to 0.66). Summary scores for the VSS, SBSES, and POSAS are presented in Table 5.

Within this subgroup of 66 patients, we observed no correlations between the POSAS, VSS, and SBSES scores and patient age, sex, type of surgery, BMI, length of wound, incision site, or thyroid weight. The only variable that showed significant correlation with the VSS and SBSES scores was duration of operation (P < 0.001) (Table 6).

When considering a cervical incision, the aesthetic outcome is highly significant because the wound is almost permanently on view, and this aspect becomes even more important if we consider that young women constitute a large proportion of patients affected by thyroid disease. In recent years, surgeons have become increasingly interested in obtaining optimal aesthetic outcomes.

Many surgical methods have been attempted for increasing cosmetic satisfaction. Some surgeons have attempted using robots or endoscopes to place the incision site in an invisible position in the axillary or periareolar area rather than the neck [3456]. Others have attempted to reduce the incision length, but this does not necessarily lead to improved patient satisfaction with the aesthetic outcomes [78]. One study compared the aesthetic appearance of cervical incisions closed with tissue glue (octyl-cyanoacrylate) versus subcuticular absorbable sutures and found that the subcuticular sutures provided better aesthetic outcomes with small cervical incisions in the early phase after thyroid surgery [12].

A wound protector made of silicone has already been demonstrated to significantly prevent surgical wound drying and to reduce the incidence of infection [9]. It has been widely used during endoscopic (laparoscopic, thoracoscopic) surgery, but there are currently no available products that can be used during thyroid surgery.

In this study, we used the EASY-EYE_C, a new silicone-based wound protector to improve the cosmetic effects of surgical wound. All scores for evaluating outcomes were higher in the E group than in the C group; we used the POSAS, VSS, and modified SBSES, which have been used in many recent studies, to assess the wounds [121314].

The POSAS is a recent and promising scar assessment tool that incorporates both observer and patient ratings (Table 1). It consists of 2 distinct scales: the OSAS and the PSAS. The POSAS was recently validated for application with linear postsurgical scars [2021]. The 2 studies found that both the OSAS and the PSAS had good internal consistency (Cronbach alpha, 0.74–0.90), and the authors also found also a significant correlation (convergent validity) between the VSS and OSAS (all P-values < 0.001) scores. The PSAS stiffness score correlated well with the VSS pliability item (P = 0.02), but there were no other significant correlations between the PSAS and the VSS [20].

Although VSS has predominantly been used mainly in the evaluation of burn scars, it was recently validated to access surgical wound and showed comparable results. In 2 cohorts of women who presented linear scars from breast cancer surgery, the results for the VSS showed acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach alpha, 0.71–0.79) but poor to moderate interrater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient, 0.03–0.64) [2022]. However, one of those demonstaded that VSS did not show clinically useful information on the patient's symptoms or perspective [20]. To overcome this problem, Nedelec et al. [23] added 2 visual analogue scales (0–10 points) regarding to itching and pain.

The modified SBSES is a relatively new scar evaluation scale that correlates well with the cosmetic visual analogue scale [14]. Kim et al. [14] made slight modifications to the SBSES by using category scores from 0 to 2 to enhance sensitivity. Because thyroidectomy scars have buried sutures, the category “hatch marks or suture marks” was changed to “incision line.”

In this study, operation duration was significantly shorter in the E group than in the C group, possibly because with the EASY-EYE_C hooks, the surgeon did not need to use the retractor or change the retractor position along the operating field as frequently. In addition, the protector covers the skin and strap muscle, which prevents the bleeding that occurs here from flowing into the surgical field; as a result, the surgeon has a good field of view during surgery and less time is spent wiping away blood. In addition, the EASY-EYE_C could be applied within 1e to 2 minutes including the time to hook it to the surgical site, and the hook positions usually did not have to be changed more than 2 times.

The wound healing process consists of the inflammatory (immediate to 2 to 5 days), proliferative (2 days to 3 weeks), and remodeling (3 weeks to 2 years) phases [24], and therefore, 2 years after an operation, the end of the remodeling phase, is considered appropriate for evaluating the final states of wounds. However, in this study, we assessed the scars 6 weeks after each operation. The reason is that a longer follow-up period might have increased the possibility of deviation from the study; more than half of the patients during that period receive treatment such as laser treatments to reduce scars of their wounds, which could have been a confounding variable in the study.

In this study, we did not exclude any of the enrolled patients because there were no contraindications to applying the EASY-EYE_C during any of the surgeries. Moreover, there were no dropouts; every patient who underwent thyroid surgery anyway visited the hospital 6 weeks after discharge for checking the thyroid function and prescribe medication.

This study has some limitations. The first relates to the fact we interrupted the trial at the checkpoint of interim analysis. Although the differences in OSAS scores were significant, for those differences, the computed power of the assessed sample was 80%, which limited the number of patients and thus possibly hid any differences in PSAS scores. Second, our follow-up was limited to 6 weeks, but it is known that the appearance of scars tends to improve with time [25]. A final limitation is that each patient was assessed by only 1 observer, and thus the objectivity of each assessment might have been lower than if we had used multiple observers.

In conclusion, many surgical methods have been attempted to increase the cosmetic satisfaction with thyroidectomy scars, including using robots and endoscopes. However, conventional thyroidectomy is standard in most patients and will continue to be for a number of reasons; it is standard with advanced thyroid cancer patients, many hospitals cannot afford expensive equipment such as robots and endoscopes, and few surgeons have the necessary advanced skills.

In this study, all outcome scores in the E group were superior to those in the C group, and operation time was significantly reduced. Therefore, the EASY-EYE_C may be a useful option for improving the cosmetic effects following conventional thyroid surgery.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 3

Six-week postoperative wound of patients using ‘EASY-EYE_ C’ (A) and not using ‘EASY-EYE_C’ (B).

Fig. 4

The mean difference in the total scores of OSAS, PSAS and POSAS (A) in the each score of 14 subdomains (B). Subdomain scores between experimental group (E group) and control group (C group) were significant for all 14 subdomains. POSAS, Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale; OSAS, Observer Scar Assessment Scale; PSAS, Patient Scar Assessment Scale.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by funding from the Ildong Pharmaceutical Company, Korea. The authors would like to thank KY LEE for giving advice about the evaluation of the wound scar.

References

1. Economopoulos KP, Petralias A, Linos E, Linos D. Psychometric evaluation of Patient Scar Assessment Questionnaire following thyroid and parathyroid surgery. Thyroid. 2012; 22:145–150.

2. Bokor T, Kiffner E, Kotrikova B, Billmann F. Cosmesis and body image after minimally invasive or open thyroid surgery. World J Surg. 2012; 36:1279–1285.

3. Katz L, Abdel Khalek M, Crawford B, Kandil E. Robotic-assisted transaxillary parathyroidectomy of an atypical adenoma. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2012; 21:201–205.

4. Alvarado R, McMullen T, Sidhu SB, Delbridge LW, Sywak MS. Minimally invasive thyroid surgery for single nodules: an evidence-based review of the lateral miniincision technique. World J Surg. 2008; 32:1341–1348.

5. Terris DJ, Seybt MW. Classification system for minimally invasive thyroid surgery. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2008; 70:287–291.

6. Kang SW, Jeong JJ, Yun JS, Sung TY, Lee SC, Lee YS, et al. Gasless endoscopic thyroidectomy using trans-axillary approach; surgical outcome of 581 patients. Endocr J. 2009; 56:361–369.

7. O'Connell DA, Diamond C, Seikaly H, Harris JR. Objective and subjective scar aesthetics in minimal access vs conventional access parathyroidectomy and thyroidectomy surgical procedures: a paired cohort study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008; 134:85–93.

8. Toll EC, Loizou P, Davis CR, Porter GC, Pothier DD. Scars and satisfaction: do smaller scars improve patient-reported outcome? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012; 269:309–313.

9. Edwards JP, Ho AL, Tee MC, Dixon E, Ball CG. Wound protectors reduce surgical site infection: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Surg. 2012; 256:53–59.

10. Lira RB, de Carvalho GB, Vartanian JG, Kowalski LP. Protecting the skin during thyroidectomy. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2014; 41:68–71.

11. Lee YS, Kim BW, Chang HS, Park CS. Use of a silicone penrose drain to protect incised skin edges during thyroid surgery. Surg Innov. 2013; 20:NP1–NP2.

12. Consorti F, Mancuso R, Piccolo A, Pretore E, Antonaci A. Quality of scar after total thyroidectomy: a single blinded randomized trial comparing octyl-cyanoacrylate and subcuticular absorbable suture. ISRN Surg. 2013; 2013:270953.

13. Vercelli S, Ferriero G, Sartorio F, Stissi V, Franchignoni F. How to assess postsurgical scars: a review of outcome measures. Disabil Rehabil. 2009; 31:2055–2063.

14. Kim YS, Lee HJ, Cho SH, Lee JD, Kim HS. Early postoperative treatment of thyroidectomy scars using botulinum toxin: a split-scar, double-blind randomized controlled trial. Wound Repair Regen. 2014; 22:605–612.

15. Draaijers LJ, Tempelman FR, Botman YA, Tuinebreijer WE, Middelkoop E, Kreis RW, et al. The patient and observer scar assessment scale: a reliable and feasible tool for scar evaluation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004; 113:1960–1965.

16. Simcock JW, Armitage J, Dixon L, MacFarlane K, Robertson GM, Frizelle FA. Skin closure after laparotomy with staples or sutures: a study of the mature scar. ANZ J Surg. 2014; 84:656–659.

17. Huppelschoten AG, van Ginderen JC, van den Broek KC, Bouwma AE, Oosterbaan HP. Different ways of subcutaneous tissue and skin closure at cesarean section: a randomized clinical trial on the long-term cosmetic outcome. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013; 92:916–924.

18. Maher SF, Dorko L, Saliga S. Linear scar reduction using silicone gel sheets in individuals with normal healing. J Wound Care. 2012; 21:602604–606. 608–609.

19. Sullivan T, Smith J, Kermode J, McIver E, Courtemanche DJ. Rating the burn scar. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1990; 11:256–260.

20. Truong PT, Lee JC, Soer B, Gaul CA, Olivotto IA. Reliability and validity testing of the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale in evaluating linear scars after breast cancer surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007; 119:487–494.

21. van de Kar AL, Corion LU, Smeulders MJ, Draaijers LJ, van der Horst CM, van Zuijlen PP. Reliable and feasible evaluation of linear scars by the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005; 116:514–522.

22. Truong PT, Abnousi F, Yong CM, Hayashi A, Runkel JA, Phillips T, et al. Standardized assessment of breast cancer surgical scars integrating the Vancouver Scar Scale, Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire, and patients' perspectives. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005; 116:1291–1299.

23. Nedelec B, Shankowsky HA, Tredget EE. Rating the resolving hypertrophic scar: comparison of the Vancouver Scar Scale and scar volume. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2000; 21:205–212.

24. Jablonka EM, Sherris DA, Gassner HG. Botulinum toxin to minimize facial scarring. Facial Plast Surg. 2012; 28:525–535.

25. Lombardi CP, Bracaglia R, Revelli L, Insalaco C, Pennestri F, Bellantone R, et al. Aesthetic result of thyroidectomy: evaluation of different kinds of skin suture. Ann Ital Chir. 2011; 82:449–455.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download