INTRODUCTION

Surgical resection for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has been a beneficial treatment option for long-term survival. Early HCC has been the preferred candidate for resection, because the 5-year disease-free survival rate is approximately 50%. Although small HCC (<2 cm) has shown diverse outcomes in terms of clinicopathologic features after surgical resection, it is considered to have a good prognosis [

12].

However, surgical resection is not always mandatory for HCC. HCC typically develops in multiple locations, and can appear in combination with liver cirrhosis and other comorbidities. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is a novel local treatment for preserving the hepatic parenchyma and preventing liver failure after surgical resection [

3]. RFA exhibits similar outcomes to those of surgical resection in terms of overall and disease-free survival, especially for very-early-stage HCC by the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer classification [

45]. In addition, compared to surgical resection, RFA is associated with a shorter hospital stay and a lower complication rate [

6]. However, when the HCC is located in a subcapsular lesion, it is likely to rupture during ablation, while when it is adjacent to organs and vessels, RFA can damage these organs. Although there are many techniques to facilitate successful percutaneous RFA, the risk of organ injury and tumor seeding still exists.

The purpose of this study was to examine the clinical outcomes of laparoscopic RFA in patients with single, small (≤3 cm), primary or recurrent HCC that was unsuitable for percutaneous RFA. We also analyzed the local tumor progression rate after the laparoscopic procedure.

Go to :

METHODS

Patient selection

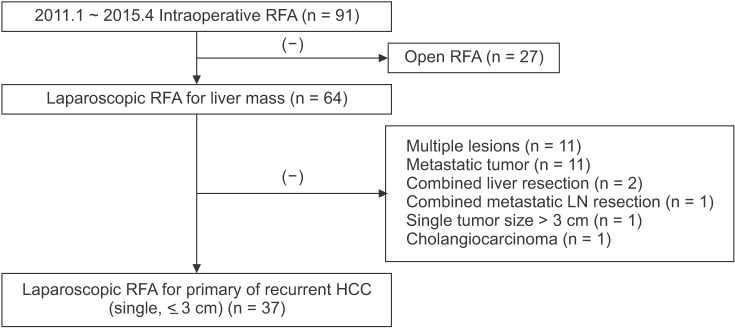

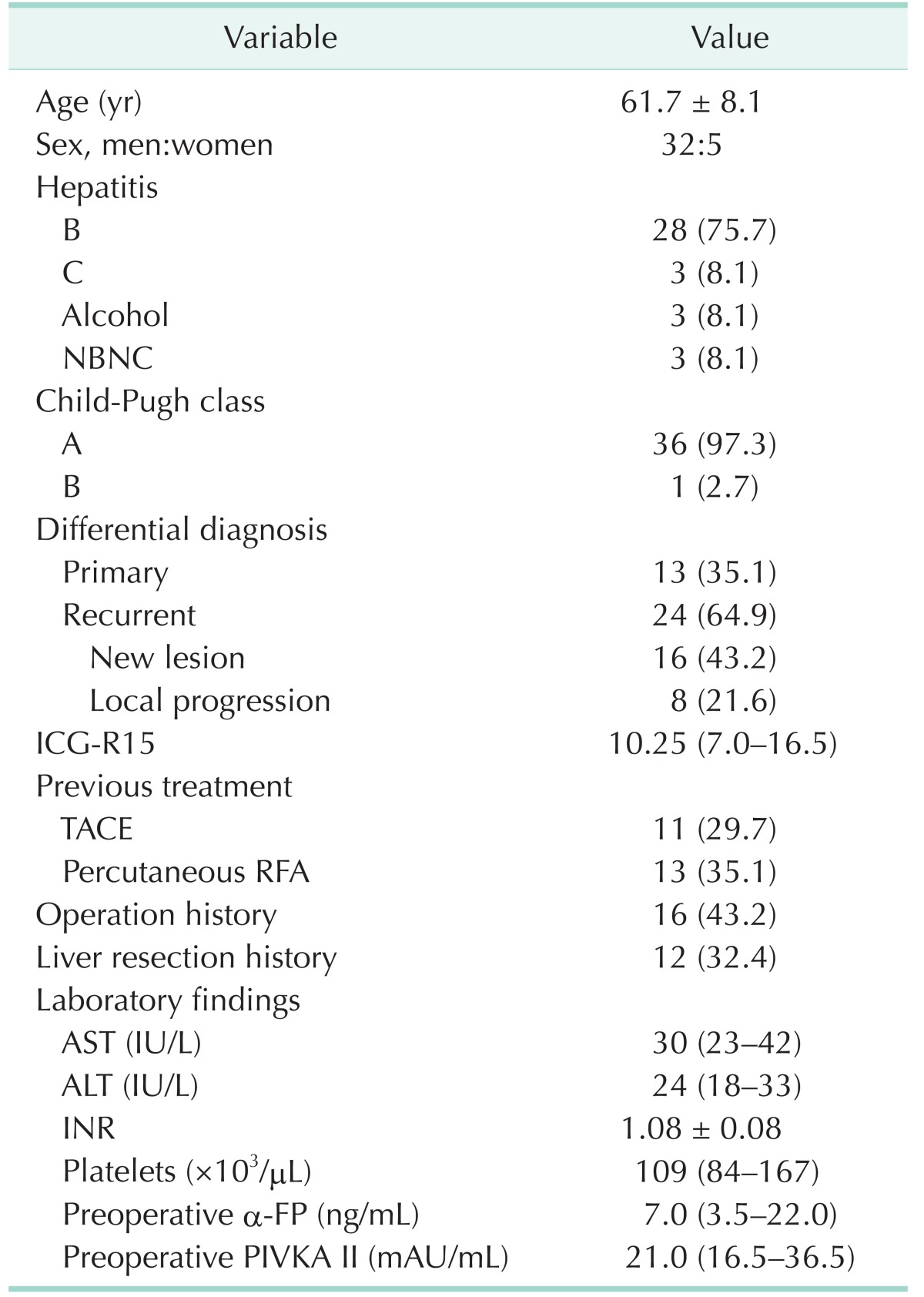

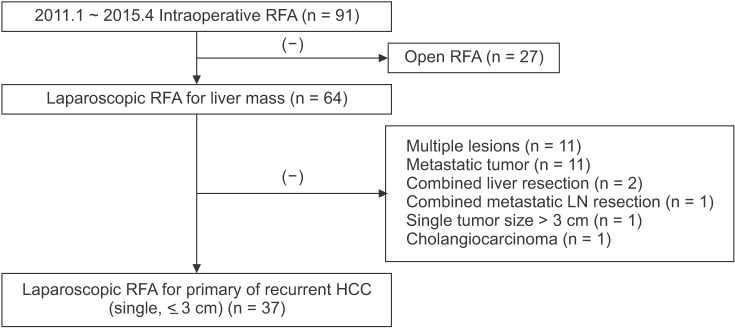

This was a single-center descriptive study that was based on a retrospective analysis of RFA for HCC via open or laparoscopic surgery. Between January 2011 and April 2015, a total of 91 patients with HCC underwent a RFA procedure at Samsung Medical Center. If a patient had a resectable Child-Pugh class A tumor, surgical resection was recommended as first-line treatment and local treatment as an alternative option. RFA was only performed if the patient expressed a preference for less invasive treatment. This retrospective study protocol was approved by our Institutional Review Board and waived the requirement for informed consent.

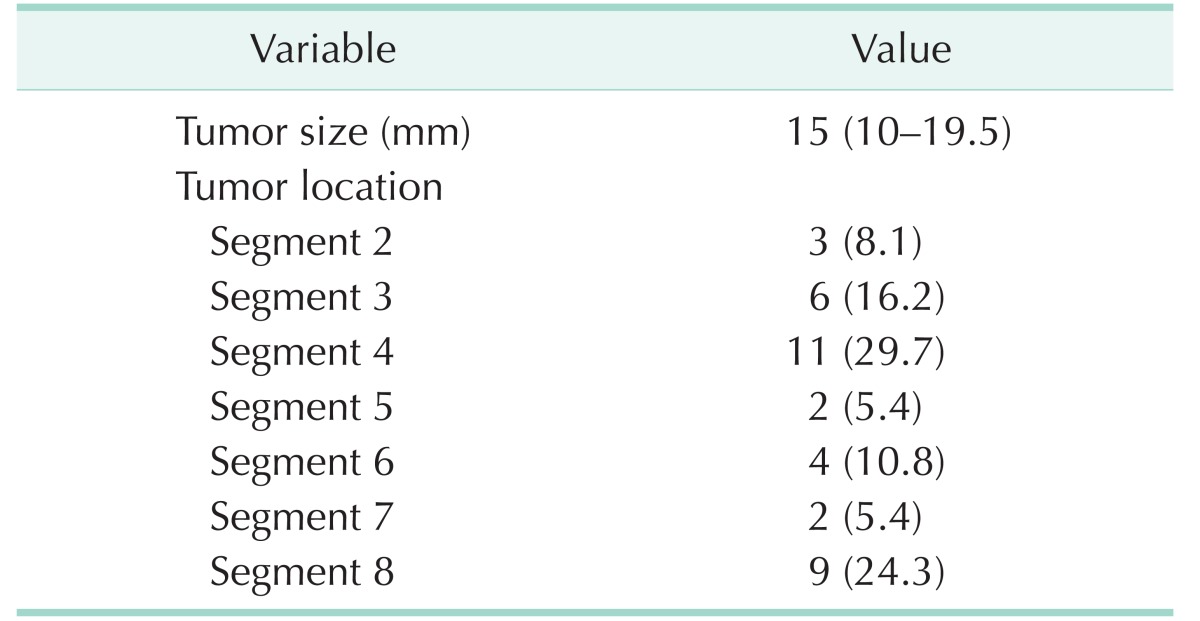

RFA was performed via open surgery in 27 patients, whereas a laparoscopic approach was used in 64. Of these, 37 patients who had a single and small (≤3 cm) HCC were included in this study. Preoperative planning ultrasonography (US) established that they were not eligible for percutaneous RFA for the following reasons: (1) poor sonic window to delineate the tumor because of the depth and location of the tumor (n = 21, 56.8%); (2) adjacent organs close to the tumor, such as the diaphragm, heart, gallbladder, stomach, and colon (n = 7, 18.9%); or (3) adjacent major vessels, such as inferior vena cava, portal vein, hepatic vein, and collaterals (n = 9, 24.8%). Cases with multiple HCC lesions were excluded because of the difficulty of assessing the technical success of laparoscopic RFA for individual tumors (

Fig. 1).

| Fig. 1Flowchart of the study population. Patients undergoing radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for single, small (≤3 cm), and primary or recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). LN, lymph node.

|

Laparoscopic RFA procedure

All patients underwent scheduled surgery under general anesthesia. A 12-mm laparoscopy trocar was placed in a subumbilical incision and two 5-mm trocars were inserted in the subcostal area bilaterally to handle the liver. After the dissection of ligaments around the liver and adhesive tissue, another 12-mm trocar was placed in the upper middle quadrant of the abdomen for the US probe (Aloka Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Once the target tumor was considered to be exposed, intraoperative US was performed so the lesion could be confirmed by the surgeon and radiologist. The tumor size and the distance between the abdominal wall and index tumor were then measured to determine the puncture site. A radiologist inserted the electrode percutaneously to the correct position in the index tumor. RFA was conducted using internally cooled electrode systems with generators (Cool-tip RF System, Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA; or VIVA RFA System, STARmed, Goyang, Korea) by 1 of 2 radiologists with sufficient experience in RFA. The 15-G or 17-G electrode and the single- (Proteus RF Electrode, STARmed) or multiple-separable-electrode (Octopus electrode, STARmed) were deployed by a radiologist. It was difficult to achieve a sufficient ablation margin when there was a poor sonic window due to echogenic bubbles after initial ablation with a single electrode. The multiple separable electrodes were applied using overlapping ablation techniques to overcome such shortcomings. Ablative treatment consisted of one or more cycles on the tumor lesion to accomplish complete ablation. The RFA energy was transmitted for 6–12 min per ablation. On completion of the procedure, we cauterized the tract during electrode removal to prevent postoperative bleeding.

Follow-up

For evaluation of postoperative outcomes and complications, all patients underwent CT after the procedure on the operative day. The ablation margin secured was at least 5 mm. If a residual lesion was detected on CT, additional RFA was attempted via a laparoscopic or percutaneous approach on the following day. For therapeutic efficacy, technical success was defined as complete ablation of the index tumor on follow-up imaging after the procedure. Once complete ablation was achieved, the primary effectiveness rate was evaluated 1 month after initial discharge, and tumor markers such as serum α-FP and protein induced by vitamin K absence/antagonism II were also measured. The follow-up policy was described in a previous study [

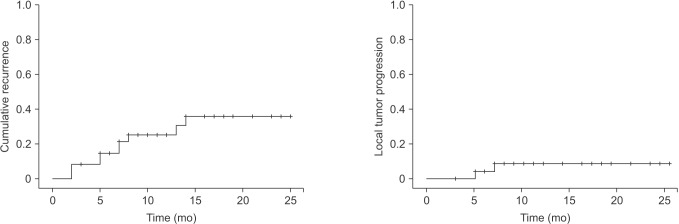

27]. Local tumor progression was defined as the appearance of enhanced tumor around the ablation zone on follow-up CT. New lesions, as represented by intrahepatic metastases, were defined as newly developed tumors away from the ablation zone on CT.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed for all variables. Categorical variables are shown as frequencies/percentages. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data and median (interquartile range) for nonnormally distributed data. Overall survival curves and cumulative recurrence curves were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS ver. 18.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

Go to :

DISCUSSION

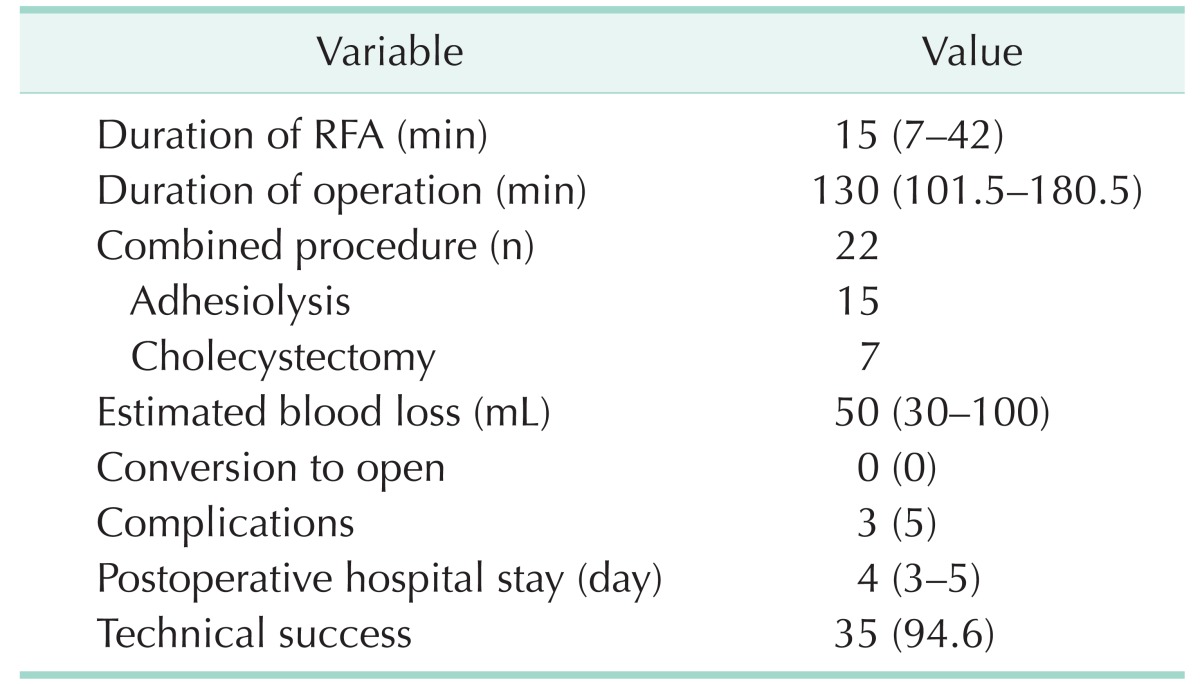

In this study, we showed that laparoscopic RFA of single, small (≤3 cm), recurrent or primary HCC has a low rate of perioperative morbidity (5%) and no associated mortality. The 2-year local tumor progression rate and intrahepatic distant recurrence rate were 7.3% and 30%, respectively. The postoperative hospital stay after RFA was short (3.6 ± 1.3 days) in our study compared with that reported in another study [

8]. This result may be attributed to the low rate of morbidities and mild complications, such as Clavien-Dindo class I. Although 2 cases had technical failure, there was no case of incomplete ablation at the 1-month follow-up evaluation.

Herbold et al. [

8] evaluated the outcomes of laparoscopic RFA for HCC in 34 consecutive patients from 2002 to 2008. They performed laparoscopic RFA instead of percutaneous RFA when the tumor was located within 1 cm of the liver capsule or in the dome of the liver. Laparoscopic RFA was also indicated when the size of the tumor to be treated was larger than 25 mm. The mean tumor size was 32.1 mm. During a mean follow-up period of 36.9 months, the local tumor recurrence rate was 61.8%. The investigators found no perioperative mortality within 30 days and no surgical complications, except for 1 patient with a transitory decrease in liver function and ascites.

Birsen et al. [

9] analyzed the 90-day morbidity and mortality of 910 patients who underwent a total of 1,207 laparoscopic RFA procedures for 2,890 malignant liver tumors between 1996 and 2012. In this large study, they found that laparoscopic RFA was associated with a complication rate of 4% (n = 50) and a mortality of 0.4% (n = 5). A total of 5 patients needed laparotomy because of postoperative bleeding from the liver (n = 4) or mesentery (n = 1). In all cases of bleeding from the liver, the target lesions were located in the right posterior section. Since these tumors required the longest needle insertion tract, there was a greater likelihood of injuring vessels.

Other studies related to RFA have reported a morbidity ranging between 0% and 34.7%, and mortality between 0% and 5.2%, regardless of approach [

1011].

Our results regarding morbidity and mortality are similar to those of the above-mentioned studies. However, all cases with postoperative morbidity improved spontaneously without any treatment. Furthermore, none of the patients developed postoperative bleeding or mortality. Cauterization of the needle tract during withdrawal could prevent postoperative parenchymal bleeding, especially in cases involving the right posterior section.

The procedure-related complications are mainly visceral damage, intraperitoneal bleeding, and tumor seeding. Kasugai et al. [

12] showed that small vessel adhesion around the liver due to previous open surgery is a risk factor for bleeding during procedures. Yeung et al. [

13] reported a case of delayed colonic perforation diagnosed on the eighth day after RFA. They suggested percutaneous RFA for lesions, especially those within 1 cm of the colonic wall, and for patients with a history of abdominal surgery. A laparoscopic or open approach has also been suggested, because the colon can safely be mobilized away from the target lesion. Kang et al. [

14] assessed factors affecting the technical failure of percutaneous RFA using artificial ascites in 113 patients with or without a history of previous HCC treatment. There was some risk of injury to the adjacent organ with conventional percutaneous RFA. Consequently, they tried to create artificial ascites around the target lesion via catheter to avoid thermal damage from the RFA. The technical success rate for the formation of artificial ascites was 84.1%. However, this rate decreased to 55.8% in patients with previous hepatic resection. The multivariate study showed that a history of hepatic resection was a significant independent predictive factor affecting the technical failure of artificial ascites formation. In our study, of the 16 patients (43.2%) with a prior history of abdominal operation, 12 (32.4%) had a history of liver resection. However, in spite of this history, 11 of these patients underwent a technically successful laparoscopic ablation, despite adhesions in the operative field. The laparoscopic RFA approach can substitute for the artificial ascites of percutaneous RFA and enable sufficient mobilization and dissection around the liver to achieve accurate ablation of the target lesion without injury to adjacent organs and vessels.

Laparoscopic US is useful for RFA. Asahina et al. [

15] suggested that mandatory use of laparoscopic US could prevent thermal damage to intrahepatic vessels and bile ducts. Furthermore, effective tumor ablation without a “heat sink” effect could be possible. In our practice, intraoperative US played a pivotal role in determining the width and depth of the tumor and the most satisfactory placement of needles around the target lesion. All procedures should begin with an appropriate arrangement of electrodes along the contour of the lesion, without direct puncture of a tumor. Efficient overlapping ablation can then be performed safely, without rupture and dissemination of the tumor. Consequently, laparoscopic US can render accurate ablation of a target lesion possible and lead to a higher rate of technical success, which reached 94.6% in our practice.

The portal and hepatic veins are main routes for the dissemination of HCC. The tumor can invade the portal branches and spread tumor emboli over the neighboring branches of the same segment [

16]. Local tumor progression after RFA may be caused by insufficient ablation of the primary tumor or the presence of tumor venous dissemination in the adjacent regions of the liver. Considering tumor dissemination, surgical resection is fundamental treatment for HCC. Accordingly, RFA must be alternative treatment to patient not suitable for resection.

The benefits of minimally invasive surgery made laparoscopic approach applicable to RFA. Topal et al. [

17] indicated that laparoscopic RFA (n = 61), compared with open RFA (n = 12), was associated with lower intraoperative blood loss, shorter duration of operation, fewer postoperative complications, and shorter postoperative hospital stay in subgroup analysis that included small tumor (≤3 cm) cases after exclusion of cases with simultaneous and/or hepatic resection. In consideration of technical aspect, open RFA may be treatment option to the cirrhotic patient with larger tumor (>3 cm).

In this study, there were some limitations. First, it was not a prospective study. There was also a selection bias related to baseline liver disease, previous treatment, and liver function. Second, our study could not show that the comparison of laparoscopic RFA with open RFA because of small cases. This study was focused on the description of laparoscopic RFA. More data from multiple centers and with long-term follow-up after laparoscopic RFA will be needed to validate this approach.

In conclusion, as described above, our practice of laparoscopic RFA for single, small (≤3 cm), and primary or recurrent HCC was associated with a low rate of complications and mortality. Furthermore, a similarly low rate of tumor recurrence has been shown in other studies. Laparoscopic US can facilitate safe and efficient laparoscopic RFA in spite of adhesions. Consequently, laparoscopic RFA is appropriate for certain HCC cases in which percutaneous RFA is not indicated.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download