Abstract

We present the case of young female patient presenting with acute onset abdominal pain. Abdominopelvic CT revealed herniation through the foramen of Winslow. The patient was transferred to our hospital and underwent laparoscopic exploration. Though spontaneous reduction was detected, segmental resection of the impacted small bowel was inevitable due to ischemic change. Our case suggests that reducing the time until surgery is very important to lower the probability of bowel resection in case of small bowel herniation through the foramen of Winslow.

The foramen of Winslow is the normal window between the greater and lesser peritoneal cavities. The anterior, posterior, superior and inferior boundaries of this foramen include the hepatoduodenal ligament, inferior vena cava, caudate lobe of the liver, and duodenum, respectively [1].

Since the first report of foramen of Winslow hernias by Blandin in 1834, there have been fewer than 200 reported cases [2]. Usually surgical management is mandatory; however, in some cases spontaneous reduction occurred resulting in avoidance of bowel resection. Here, we report a case of spontaneous reduction of small bowel herniation through the foramen of Winslow; however, bowel resection was inevitable.

A 32-year-old female with no previous operation history, presented to the Emergency Department with acutely developed epigastric and right upper quadrant pain with a 5-hour duration. The patient was transferred from a local clinic for proper management of bowel herniation. The abdominal pain was associated with nausea and vomiting. The character of abdominal pain was continuously sharp and squeezing.

Physical examination showed direct tenderness without guarding or peritoneal irritation. Bowel sounds were normal with no bowel distention. Laboratory examination was unremarkable except leukocytosis (16,000/µL).

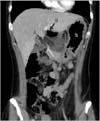

Abdominal CT performed in a local hospital had revealed a small bowel herniation through the foramen of Winslow (Fig. 1). The patient underwent an urgent exploratory laparoscopy using one 12-mm umbilical port and two 5-mm working ports in the left lateral and right lateral abdominal walls. After pneumoperitoneam was established, we traced the small bowel from the terminal ileum to the Treitz ligament. There was a moderate amount of hemorrhagic fluid in the intraperitoneal cavity. The previously indicated small bowel herniation site by the abdominal CT was not detected. However, severe congestion consisting of about 30 cm of the small bowel was noted in the mid jejunum, suspected to be the impacted lesion. Injured segments of small bowel were extracted through a mini laparotomy made using the extended umbilical port. Segmental resection of the small bowel with side to side anastomosis was performed. After a hemovac was inserted in the perihepatic space, the abdominal wall was closed, and the operation was completed.

No complications occurred during the postoperative period. The patient started on a clear liquid diet on postoperative day 4, and was discharged on postoperative day 6. Mucosal ischemic change with submucosal edema was shown on pathologic findings of the resected small bowel. At the first follow-up, the patient reported no complication.

Herniation through the foramen of Winslow is a rare event and accounts for 8% of all internal hernias [3]. The clinical presentation is usually non-specific, and the spectrum of symptoms ranges from upper abdominal pain to signs and symptoms of acute bowel obstruction such as nausea and vomiting [123456789].

The most common viscus of the foramen of Winslow herniation is the small bowel (36%) followed by the cecum and right colon (30%) and the transverse colon (7%) [10]. The exact cause is not well understood but several factors are known as predisposing factors. These factors include anatomical abnormalities, such as enlarged foramen of Winslow, long small bowel mesentery, incomplete adhesion of the bowel to the posterior abdominal wall causing increased bowel mobility, and acquired factors that increase intra-abdominal pressure [14]. Mostly through radiologic study, the causative viscus can be preoperatively identified. In our case, CT scan revealed a small bowel herniation through the foramen of Winslow.

Operative management is the treatment of choice for such hernias. Most reports describe reduction via gentle traction or by opening the lesser sac [7]. Needle decompression can be performed as a useful method to facilitate gentle reduction [1]. However, when the bowel is nonviable, bowel resection should be performed. It is controversial whether or not to close the foramen of Winslow. Due to possible complications such as portal vein thrombosis and damage to the portal vein, hepatic artery, or bile ducts, most cases did not execute primary repair [79]. There is debate on the usefulness of this preventive management since lack of evidence on recurrent herniation [137]. We did not perform primary repair of the foramen of Winslow for fear of injury to the vital hepatobiliary structure. Moreover, it was practically very difficult to determine the anatomy of the foramen of Winslow using a laparoscopic approach.

Historically laparotomy has been the initial choice of surgery for hernia. However, laparoscopic surgery is being used and is a general tendency [1]. The laparoscopic approach has been shown to be safe and feasible (Table 1). Additionally, some authors have insisted that management using laparoscopy decreases the risk of complication [1]. In our case, we started with a laparoscopic approach. At the beginning of the operation, the herniated small bowel was already spontaneously reduced. However, due to severe ischemic change and low motility of the small bowel, segmental resection of the impacted small bowel was inevitable. We assume that if we could have reduced the ischemic time after the herniation event without transfer from a local clinic to our hospital, small bowel resection could have been avoided.

In our case spontaneous reduction occurred presumably due to the muscle relaxing effects of the anesthesia. Because spontaneous reduction can occur in small bowel herniation through the foramen of Winslow, our case suggests that reducing the time until surgery is very important to lower the probability of bowel resection.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Harnsberger CR, McLemore EC, Broderick RC, Fuchs HF, Yu PT, Berducci M, et al. Foramen of Winslow hernia: a minimally invasive approach. Surg Endosc. 2015; 29:2385–2388.

2. Ferguson RA, Paget C, Ferrara J. Selective nonoperative management of foramen of Winslow hernias. Am Surg. 2015; 81:E141–E142.

3. Patel V, Newton R, Wakely S, Rajaratnam K, Ramesh S. Caecal herniation through the foramen of Winslow: a rare cause of bowel obstruction. Updates Surg. 2013; 65:241–244.

4. Daher R, Montana L, Abdul lah J, d'Alessandro A, Chouillard E. Laparoscopic management of foramen of Winslow incarcerated hernia. Surg Case Rep. 2016; 2:9.

5. Garg S, Flumeri-Perez G, Perveen S, DeNoto G. Laparoscopic repair of foramen of Winslow hernia. Int J Angiol. 2016; 25:64–67.

6. May A, Cazeneuve N, Bourbao-Tournois C. Acute small bowel obstruction due to internal herniation through the Foramen of Winslow: CT diagnosis and laparoscopic treatment. J Visc Surg. 2013; 150:349–351.

7. Powell-Brett SF, Royle JT, Stone T, Clarke RG. Caecum herniation through the Foramen of Winslow. J Surg Case Rep. 2012; 12. 11. 2012(12):DOI: 10.1093/jscr/rjs016.

8. Puig CA, Lillegard JB, Fisher JE, Schiller HJ. Hernia of cecum and ascending colon through the foramen of Winslow. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013; 4:879–881.

9. Sikiminywa-Kambale P, Anaye A, Roulet D, Pezzetta E. Internal hernia through the foramen of Winslow: a diagnosis to consider in moderate epigastric pain. J Surg Case Rep. 2014; 06. 25. 2014(6):DOI: 10.1093/jscr/rju065.

10. Erskine JM. Hernia through the foramen of Winslow. A case report of the cecum incarcerated in the lesser omental cavity. Am J Surg. 1967; 114:941–947.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download