Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to compare clinical outcomes for single-incision laparoscopic appendectomy (SILA) and conventional laparoscopic appendectomy (CLA) for the treatment of acute appendicitis and to assess the feasibility of performing SILA in a small hospital with limited surgical instruments and staff experience.

Methods

Retrospective record review identified 133 patients who underwent laparoscopic appendectomy from December 2013 to April 2015. Patients were categorized according to the type of appendectomy performed (SILA or CLA). Patient characteristics and surgical outcomes were compared between the 2 groups. Postoperative complication rates were compared using the Clavien-Dindo classification. Postoperative pain was assessed using a visual analog scale immediately postsurgery; at 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours postoperatively, and at 7 days postoperatively.

Results

Record review identified 38 patients who had undergone SILA and 95 patients who had undergone CLA. No significant differences in clinical characteristics were found between the 2 groups. There were no significant differences in operation time, time to flatus, or length of hospital stay. Overall complication rates were not significantly different between the 2 groups. No complications worse than grade IIIa occurred in the SILA group. Postoperative pain scores were not significantly different between the 2 groups at any time point.

Conventional laparoscopic appendectomy (CLA) using three port incisions is accepted as the standard technique for patients with acute appendicitis [1]. CLA has been shown to have several advantages over an open approach, including less surgical trauma, faster recovery, decreased complications, less postoperative pain, and improved cosmetic outcomes [234]. Although the results of CLA are already excellent, surgeons have sought to develop techniques to further reduce surgical trauma and to improve cosmetic outcomes for patients. Therefore, as single-site access laparoscopic procedures have become a rapidly evolving trend in the surgical field, single-incision laparoscopic appendectomy (SILA) has recently gained popularity as a treatment for acute appendicitis [56].

To date, there have been several randomized clinical trials comparing outcomes for SILA and CLA [789]. However, a consensus regarding the objective benefits of SILA has not been reached [10]. Furthermore, previously published randomized clinical trials comparing these procedures were conducted in general hospitals with large numbers of patients and excellent surgical environments [6]. Therefore, it remains a debatable issue whether SILA can be performed safely as an alternative procedure for CLA in smaller hospitals with more limited surgical instruments and staff experience.

Currently, CLA is the standard treatment for acute appendicitis in the Korean Armed Forces Hospital. However, military service is compulsory for all healthy young men in Korea, and particularly in this patient population, less invasive surgery might permit faster return to vigorous activity. Although SILA is occasionally performed at the Armed Forces Capital Hospital, SILA is not the preferred operation for appendicitis in the majority of smaller Korean Armed Forces Hospitals due to limited surgical instrument availability and staff experience [11]. Thus, this study aimed to compare clinical outcomes for SILA and CLA and to assess the feasibility of performing SILA in a small hospital with limited surgical instruments and staff experience.

Retrospective record review identified 133 patients who had undergone laparoscopic appendectomy from December 2013 to April 2015, at the Armed Forces Ildong Hospital by four surgeons skilled in CLA. A diagnosis of acute appendicitis was suspected when a patient presented with a history of right lower quadrant abdominal pain or periumbilical pain migrating to the right lower quadrant, with nausea and/or vomiting, right lower quadrant guarding, and abdominal tenderness on physical examination [12]. The diagnosis of acute appendicitis was confirmed using contrast-enhanced abdominal CT to identify typical findings of acute appendicitis [13].

The type of surgery was chosen based on patient preference after written informed consent was obtained. SILA was performed for patients who had acute appendicitis even in the presence of perforation. However, SILA was not performed for patients who had generalized peritonitis after perforation, severe adhesions due to prior surgery, or incidental identification of another disease on preoperative abdominal CT. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Armed Forces Medical Command (AFMC-16002-IRB-16-001).

A 2.0-cm transumbilical vertical skin incision was used for single-site access. After the skin incision was made, a wider, approximately 3.0-cm incision, was made in the umbilical fascia. A single-incision laparoscopic surgery port (S-Oneport, ERAE SI, Seoul, Korea) with 3 trocar channels was then inserted into the access site incision (Fig. 1A). After pneumoperitoneum was achieved, a rigid 30° 5-mm telescope was placed into the peritoneal cavity. Two laparoscopic instruments were then introduced into the peritoneal cavity. Only straight-type instruments were used. Under direct visualization, ultrasonic coagulating shears (Harmonic Scalpel, Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA) were used to dissect the mesoappendix and appendiceal artery. The appendix base was then ligated using an endoloop absorbable thread (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA) and divided using a Harmonic Scalpel. Extraction of the appendix was done using a specimen retrieval bag (Endocatch; Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA). If an additional trocar was needed, skin and fascial incisions were made and a 5-mm extra trocar was inserted in the suprapubic area. A closed-suction drain was inserted at the suprapubic additional trocar site when perforated appendicitis was discovered intraoperatively. At the conclusion of the procedure, the fascia was closed using running 2-0 absorbable suture (Vicryl, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA), and skin incisions were closed using interrupted 4-0 absorbable subcuticular sutures (Fig. 1B).

CLA required the introduction of a 30° 10-mm rigid scope through a 1-cm infraumbilical incision. Two additional 5-mm incisions were made in the suprapubic area and the left lower quadrant for the insertion of working ports. Working through these 3 ports, the intra-abdominal appendectomy procedure was same as described for the SILA procedure above. Appendix specimens were retracted using a specimen retrieval bag and removed through the infraumbilical incision. The infraumbilical fascia was closed using running 2-0 absorbable suture. Skin incisions were closed using a skin stapler device.

Patients received routine intravenous administration of 1 g of ceftriaxone every 24 hours from the time of diagnosis until postoperative day 1. In cases of perforated or gangrenous appendicitis, 500-mg metronidazole was added every 8 hours until fever was relieved. Sips of water were started on the day of first flatus, and advancement to a regular diet depended on each patient's individual condition. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were routinely injected every 8 hours via an intravenous catheter until the day after surgery. Additional pain medications were given according to the surgeon's judgment if pain was not relieved. No opioids were used for pain control. Patients were discharged when they were tolerating a regular diet and no other specific symptoms were present. Regular follow-up was not needed.

Patient characteristics and surgical outcomes for SILA and CLA were investigated. Clinical characteristics included in the analysis were age, sex, body mass index (BMI), presence of perforated appendicitis, presence of retrocecal appendix, and laboratory data (WBC count, neutrophil percentage, platelet count, CRP, total bilirubin, AST, ALT, PT, and aPTT). Surgical outcome measures included operative time, time to first flatus, time to regular diet, length of hospital stay, postoperative pain scores, and the occurrence of postoperative complications. Perforated appendicitis and retrocecal appendix were assessed at the time of surgery. The operative time was defined as the duration of surgery, beginning with the skin incision and ending with the application of the final wound dressing. The time to first flatus was defined as the time until the patient's notification to the care team of first gas passage after surgery. The length of hospital stay was calculated by considering the day of operation as day 0. Postoperative pain scores were recorded using a standard visual analog scale and were assessed immediately postsurgery, at 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours, postoperatively, and at 7 days postoperatively. Postoperative complications were assessed using the Clavien-Dindo classification [14]. Wound problems were defined as surgical site infections or the occurrence of wound dehiscence. Ileus and intra-abdominal abscess were diagnosed using radiologic criteria.

An independent Student t-test and repeated measures analysis of variance were used for comparisons of continuous variables. Categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square tests. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS ver. 18.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA), and statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

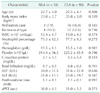

Records were reviewed for 133 patients with acute appendicitis who underwent laparoscopic appendectomy. Among these patients, 38 underwent SILA and 95 underwent CLA. All patients were male, and mean age was 21.4 years. No significant differences between groups were found for age, BMI, incidence of perforation, or presence of retrocecal appendix. In addition, there were no statistical differences between the 2 groups in the laboratory test results (Table 1).

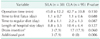

Mean operative time was slightly longer in the SILA group compared to CLA, but this difference in operative times was not statistically significant (Table 2). There was no significant difference between groups in time to first flatus, time to regular diet, or length of hospital stay. Three patients in the SILA group received drain insertion via an additional trocar site due to the presence of perforation of the appendix. In the CLA group, 17 patients received drain insertion: for perforated appendicitis in 16 patients and to monitor bleeding in one.

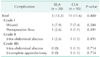

Overall postoperative complication rates were not found to be significantly different between the 2 groups. In the SILA group, grade I complications developed in 4 patients (10.5%): wound problems in three patients and ileus in 1 (Table 3). A grade II complication developed in 1 SILA patient (2.6%). In this patient, an intra-abdominal abscess was detected on follow-up CT. The patient recovered after antibiotic treatment. No complications above grade IIIa were reported in the SILA group. In the CLA group, Grade I complications developed in 8 patients (8.5%): wound problems in 7 and ileus in 1. A grade II complication developed in one CLA patient (1.1%). This patient developed an intra-abdominal abscess which was successfully treated with antibiotics. In the CLA group, 2 patients developed grade IIIb complications (2.2%). One patient developed a pelvic abscess that required reoperation. The other patient underwent a second complete appendectomy due to remnant appendicitis.

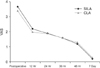

Postoperative pain scores were found to decrease gradually as time passed, and no significant differences were found between the 2 groups at any of the follow-up time points (Fig. 2).

The current study found that surgical outcomes for SILA were not significantly different from those for CLA. Complications above grade IIIa were observed only in the CLA group, and incidence rates for postoperative complications were not significantly different between the 2 groups. Postoperative pain scores at each follow-up time point also demonstrated no significant differences between the 2 groups. From these data, we conclude that SILA and CLA may achieve similar surgical outcomes in small hospital with limited surgical instruments and staff experience.

An early theoretical concern for single incision laparoscopic surgery was that reduced surgical access and visualization might compromise patient safety [15]. And early reports suggested that SILA might be associated with a higher incidence of wound infection [16]. However, as laparoscopic techniques and equipment have improved, recent studies have reported that SILA has similar postoperative complication rates to CLA [1517]. In a review of randomized trials, Markar et al. [5] found no significant difference between CLA and SILA not only in the overall incidence of surgical complications, but also in the incidence of wound infection, intra-abdominal collection, and ileus. And in their systematic meta-analysis, Xu et al. [17] also found no difference between SILA and CLA in rates of overall, surgical, or medical complications, results that these authors proposed might be due to the fact that SILA and CLA both achieve the same organ and mesoappendix resection. In agreement with 3 previous studies, our current study found no difference in complication rates between the SILA and CLA groups, and notably, there were no complications above grade IIIa in the SILA group. Therefore, the results of this study provide further support for SILA as a safe alternative procedure to CLA that does not lead to increased complication rates or severity.

Cases of complicated appendicitis were excluded from early studies of SILA because the safety of this procedure was not proven due to technical difficulties [18192021]. However, SILA has been performed for cases of complicated appendicitis in recent studies, and complication rates for SILA have not been found to be significantly greater compared to CLA [781022]. Kang et al. [22] suggested that SILA may be performed for cases of complicated appendicitis because an additional trocar can be used if needed. The use of an additional trocar provides space for triangulation, as well as a site for drain insertion. The insertion of an additional trocar may offer convenience for the surgeon, as well as enhanced patient safety. However, a recent systematic review reported that the rate of additional trocar insertion was lower during SILA than the rate of drain insertion during CLA [17]. These findings suggest that surgeons may hesitate to use an additional trocar because then more than a single incision is made. However, the use of an additional trocar should be actively considered in difficult cases for the patient's safety. In this regard, an additional trocar was used for all three patients with perforated appendicitis in the SILA group in this study. Notably, in this study, no complications above grade IIIa were observed in SILA group.

Previous studies have reported longer operative times for SILA compared to CLA [56891718]. Carter et al. [9] have suggested that operative times for SILA may be longer than CLA due to a lack of triangulation for the target organ using the SILA approach and the need to close a longer fascial incision. And Kim et al. [19] also demonstrated that technical instrument handling difficulties contributed to longer operative times. Therefore, the use of roticulating devices is recommended during SILA, and the SCARLESS Study Group has demonstrated that operation times are about 15 minutes shorter than CLA with roticulating devices [10]. However, roticulating devices are expensive and not always available in most small hospitals. Moreover, recent studies have demonstrated that similar operative times may be achieved with conventional straight devices [723]. In accordance with these recent studies, the present study used only straight laparoscopic instruments, and operation times were not found to be statistically different between the SILA and CLA groups. Therefore, our results suggest that SILA may not require longer operation times than CLA, and that conventional straight devices may be sufficient to perform SILA without an increased operative time.

Several previous reports have also suggested that SILA may be associated with greater postoperative pain than CLA, due to the use of larger transumbilical skin and fascial incisions and stretching of the surgical incision during SILA [91821]. However, there has been controversy as to whether SILA does increase postoperative pain. Frutos et al. [8] suggested that SILA resulted in less pain because the total size of the skin incisions is reduced and they do not perforate the aponeurosis and muscle. And recent prospective studies have demonstrated similar postoperative pain levels for SILA and CLA [2024]. As an explanation for these findings, Lee et al. [7] have suggested that the increase in port size for SILA may be offset by the reduced number of trocars, resulting in pain levels that are not significantly different after the 2 procedures. In accordance with these previous reports, the current study found that postoperative pain in the SILA group was not significantly different from the CLA group. Therefore, our results also suggest that SILA may not increase postoperative pain compared to CLA.

The present study does have several limitations. First, current study included only young, low BMI, male patients as a result of being conducted in a military hospital. Thus, our study was unable to assess the effectiveness of SILA in more diverse patient populations, including obese and elderly patients. Also, since the patients had to return to the military base after discharge, the length of hospital stay was longer than in previous studies conducted on civilian populations. In addition, since the type of surgery was chosen by the patient after informed consent, procedures were not randomized.

In summary, the current study found that SILA provided comparable surgical outcomes to CLA and did not result in increased postoperative complication rates. Therefore, we conclude that SILA may be performed safely as an alternative procedure for CLA, even in a small hospital with limited surgical instruments and staff experience.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Single-incision laparoscopic port. (A) The port is composed of one 5-mm and two 12-mm trocar channels. (B) The umbilical wound of single-incision laparoscopic appendectomy at immediate postoperative time. |

| Fig. 2Change of visual analog scale (VAS) pain score according to type of surgery. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. SILA, single-incision laparoscopic appendectomy; CLA, conventional laparoscopic appendectomy. |

References

1. Guller U, Hervey S, Purves H, Muhlbaier LH, Peterson ED, Eubanks S, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: outcomes comparison based on a large administrative database. Ann Surg. 2004; 39:43–52.

2. Wei B, Qi CL, Chen TF, Zheng ZH, Huang JL, Hu BG, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy for acute appendicitis: a metaanalysis. Surg Endosc. 2011; 25:1199–1208.

3. Tiwari MM, Reynoso JF, Tsang AW, Oleynikov D. Comparison of outcomes of laparoscopic and open appendectomy in management of uncomplicated and complicated appendicitis. Ann Surg. 2011; 254:927–932.

4. Lee JM, Jang JY, Lee SH, Shim H, Lee JG. Feasibility of the short hospital stays after laparoscopic appendectomy for uncomplicated appendicitis. Yonsei Med J. 2014; 55:1606–1610.

5. Markar SR, Karthikesalingam A, Di Franco F, Harris AM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of single-incision versus conventional multiport appendicectomy. Br J Surg. 2013; 100:1709–1718.

6. Antoniou SA, Koch OO, Antoniou GA, Lasithiotakis K, Chalkiadakis GE, Pointner R, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized trials on single-incision laparoscopic versus conventional laparoscopic appendectomy. Am J Surg. 2014; 207:613–622.

7. Lee WS, Choi ST, Lee JN, Kim KK, Park YH, Lee WK, et al. Single-port laparoscopic appendectomy versus conventional laparoscopic appendectomy: a prospective randomized controlled study. Ann Surg. 2013; 257:214–218.

8. Frutos MD, Abrisqueta J, Lujan J, Abellan I, Parrilla P. Randomized prospective study to compare laparoscopic appendectomy versus umbilical single-incision appendectomy. Ann Surg. 2013; 257:413–418.

9. Carter JT, Kaplan JA, Nguyen JN, Lin MY, Rogers SJ, Harris HW. A prospective, randomized controlled trial of single-incision laparoscopic vs conventional 3-port laparoscopic appendectomy for treatment of acute appendicitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2014; 218:950–959.

10. SCARLESS Study Group. Ahmed I, Cook JA, Duncan A, Krukowski ZH, Malik M, et al. Single port/incision laparoscopic surgery compared with standard three-port laparoscopic surgery for appendicectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2015; 29:77–85.

11. Lee JS, Choi YI, Lim SH, Hong TH. Transumbilical single port laparoscopic appendectomy using basic equipment: a comparison with the three ports method. J Korean Surg Soc. 2012; 83:212–217.

12. Katkhouda N, Mason RJ, Towfigh S, Gevorgyan A, Essani R. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: a prospective randomized double-blind study. Ann Surg. 2005; 242:439–448.

13. Sabiston DC, Townsend CM. Sabiston textbook of surgery: the biological basis of modern surgical practice. 19th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier Saunders;2012.

14. Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009; 250:187–196.

15. SCARLESS Study Group. Ahmed I, Cook JA, Duncan A, Krukowski ZH, Malik M, MacLennan G, et al. Single port incision laparoscopic surgery compared with standard three-port laparoscopic sugery for appendicectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2015; 29:77–85.

16. Teoh AY, Chiu PW, Wong TC, Wong SK, Lai PB, Ng EK. A case-controlled comparison of single-site access versus conventional three-port laparoscopic appendectomy. Surg Endosc. 2011; 25:1415–1419.

17. Xu AM, Huang L, Li TJ. Single-incision versus three-port laparoscopic appendectomy for acute appendicitis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2015; 29:822–843.

18. St Peter SD, Adibe OO, Juang D, Sharp SW, Garey CL, Laituri CA, et al. Single incision versus standard 3-port laparoscopic appendectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2011; 254:586–590.

19. Kim HO, Yoo CH, Lee SR, Son BH, Park YL, Shin JH, et al. Pain after laparoscopic appendectomy: a comparison of transumbilical single-port and conventional laparoscopic surgery. J Korean Surg Soc. 2012; 82:172–178.

20. Teoh AY, Chiu PW, Wong TC, Poon MC, Wong SK, Leong HT, et al. A double-blinded randomized controlled trial of laparoendoscopic single-site access versus conventional 3-port appendectomy. Ann Surg. 2012; 256:909–914.

21. Baik SM, Hong KS, Kim YI. A comparison of transumbilical single-port laparoscopic appendectomy and conventional three-port laparoscopic appendectomy: from the diagnosis to the hospital cost. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013; 85:68–74.

22. Kang KC, Lee SY, Kang DB, Kim SH, Oh JT, Choi DH, et al. Application of single incision laparoscopic surgery for appendectomies in patients with complicated appendicitis. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2010; 26:388–394.

23. Buckley FP 3rd, Vassaur H, Monsivais S, Jupiter D, Watson R, Eckford J. Single-incision laparoscopic appendectomy versus traditional three-port laparoscopic appendectomy: an analysis of outcomes at a single institution. Surg Endosc. 2014; 28:626–630.

24. Sozutek A, Colak T, Dirlik M, Ocal K, Turkmenoglu O, Dag A. A prospective randomized comparison of single-port laparoscopic procedure with open and standard 3-port laparoscopic procedures in the treatment of acute appendicitis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013; 23:74–78.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download