Abstract

Purpose

Necrotizing soft tissue infection is the infection of the soft tissue with necrotic changes. It is rare, but results in high mortality. We analyzed the characteristics of patients, prognosis, and mortality factors after reviewing 30 cases of a single hospital for 5 years.

Methods

From January 2009 to December 2013, 30 patients diagnosed with necrotizing fasciitis or Fournier's gangrene in Pusan National University Hospital were enrolled for this study. The following parameters were analyzed retrospectively: demographics, infection site, initial laboratory finding, initial antibiotics, isolated microorganisms, number of surgeries, time to first operation, length of intensive care unit, and total hospital stays.

Results

The overall mortality rate was 23.3%. Mean body mass index (BMI) of the survival group (24.7 ± 5.0 kg/m2) was significantly higher than the nonsurvival group (22.0 ± 1.4 kg/m2, P = 0.029). When BMI was less than 23 kg/m2, the mortality rate was significantly higher (P = 0.025). Two patients (6.7%) with chronic kidney disease requiring hemodialysis died (P = 0.048). Initial WBC count (>13×103/µL), CRP (>26.5 mg/dL), and platelet (PLT) count (<148×103/µL) were found to have negative impact on the prognosis of necrotizing soft tissue infection. Factors such as potassium level, blood urea nitrogen (>27.6 mg/dL), serum creatinine (>1.2 mg/dL) that reflected kidney function were significant mortality factors.

Necrotizing soft tissue infection (NSTI) is defined as the infection of any layer within the soft tissue compartment (skin, subcutaneous fat, superficial and deep fascia, or muscle) with necrotic changes [1]. Lesions on the perineum and genital area with possible infection of the abdominal wall are called "Fournier's gangrene" [2]. NSTIs including Fournier's gangrene are very rare. Most surgeons might encounter them just once or twice in their entire career. They can progress very rapidly, and need prompt debridement and specific antimicrobial therapy [34]. However, it is difficult to distinguish them from other superficial infections such as cellulitis in early stage, leading to high morbidity and mortality [5]. Despite great improvements in our understanding of NSTI and medical or surgical intensive care, the mortality of NSTI has remained at 25% to 35%, which has not improved in the last 30 years [6]. There are some studies of NSTI in United States. However, NSTI has been rarely studied in Korea. Therefore, the objective of this study was to analyze the characteristics of patients, prognosis, and mortality factors after reviewing 30 cases of NSTI in a Korean tertiary hospital for 5 years.

From January 2009 to December 2013, 31 patients were diagnosed with NSTI or Fournier's gangrene in Pusan National University Hospital. One patient died from septic shock in the emergency room shortly after admission. Except the one, a total of 30 patients medical charts were reviewed retrospectively for this study.

Laboratory tests were performed immediately after admission. They included complete blood count (hemoglobin level, WBC and platelet [PLT] count), blood chemistry (serum electrolyte, BUN, creatinine, glucose, albumin, CRP level), and coagulation tests (PT, international normalized ratio, aPTT). In addition, the presence of shock and shock index (SI) were investigated on admission. Shock was defined as the presence of arterial hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg or mean arterial pressure < 60 mmHg) despite adequate fluid resuscitation (at least crystalloid solution > 20 mL/kg). SI was defined as heart rate / systolic blood pressure.

Administration of broad spectrum antibiotics was started immediately (<24 hr) for all patients. Thereafter, antibiotics were modified according to the result of tissue culture and antibiotic susceptibility test.

Tissue culture tests were performed for all patients at the first surgery. Depending on isolated microorganisms, NSTI was classified into 2 types: type I (polymicrobial), II (monomicrobial).

The number of surgeries, time to first operation, the lengths of intensive care unit (ICU) and total hospital stays were investigated as clinical outcomes, retrospectively.

All data were analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 21.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were analyzed by an unpaired t-test, while categorical variables were analyzed by chi-square test except where 20% of cells had expected counts of <5, in which case Fisher exact test was used. All laboratory findings (continuous variables) were reanalyzed with conversion to categorical variables by calculating the cutoff value through receiver operating characteristic curve. P-values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. Significant factors in univariate analysis were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model with death.

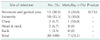

Seven of 30 patients died. Therefore, the overall mortality rate was 23.3%. The mean age of all patients was 62.6 ± 10.3 years. The male to female ratio was 23:7 (76.7%:23.3%). The mean body mass index (BMI) of the survival group was 24.7 ± 5.0 kg/m2, which was significantly higher (P = 0.029) than that of the nonsurvival group (22.0 ± 1.4 kg/m2). When BMI was less than 23 kg/m2, the mortality rate was significantly higher (P = 0.025). The most common underlying disease of all patients was diabetes mellitus (n = 18, 60.0%). Two patients (6.7%) with chronic kidney disease requiring hemodialysis died (P = 0.048). Thirteen patients (43.3%) had two or more underlying diseases. However, there was no statistical significance (P = 0.463) (Table 1).

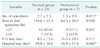

Perineum and genital area was the most common (50.0%) site of NSTI. There was no statistically significant difference in mortality according to the site of infection (P = 0.732) (Table 2).

Initial WBC count in the nonsurvival group was 19.5 ± 4.0×103/µL, which was significantly (P = 0.029) higher than that in the survival group (14.4 ± 7.2×103/µL). Mortality was significantly (P = 0.007) higher in the group with a mean WBC count of more than 13×103/µL. Mean CRP level and PLT count were not significantly different between the survival group and the non-survival group. However, mortality was significantly higher in the group with a CRP of more than 26.5 mg/dL (P = 0.025) and a PLT count of less than 148×103/µL (P = 0.014). Potassium level, BUN, and serum creatinine in the nonsurvival group were significantly higher than that in the survival group. Mortality rates were significantly higher when creatinine level was greater than 1.3 mg/dL (P = 0.004) or when BUN level was greater than 27.6 mg/dL (P = 0.009). Mortality rate was higher (33.3%) in patients in shock on admission (P = 0.193), and SI in the nonsurvival group (1.0 ± 0.4) was slightly higher than that of the nonsurvival group (0.9 ± 0.4, P = 0.457). However, they had no statistical significance (Table 3).

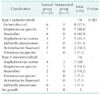

Broad-spectrum antibiotics for covering anaerobic strains with single or combined regimen were used for all patients immediately after admission. A single drug regimen was used in four (13.3%) patients. A combination drug regimen was used in 26 patients (86.7%). However, there was no difference in mortality according to the regimen (P > 0.999) (Table 4).

All patients had surgeries, including wide debridement and drainage up to 10 times (average, 2.4 ± 6.5 times). The number of surgeries was significantly (P = 0.011) different between the survival group (average, 2.7 ± 2.3 times) and the nonsurvival group (average, 1.3 ± 0.5 times). Mean time from admission to the first operation in the survival group (159.6 ± 33.3 hours) was longer than that in the nonsurvival group (64.3 ± 24.3 hours). The number of patients operated on promptly (within 24 hours after admission) in the survival group (69.6%) was slightly higher than that in the nonsurvival group (57.1%). However, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.657). Although there was no statistical significance (P = 0.113), the average length of ICU stays in the nonsurvival group was 16.3 ± 10.1 days, which was longer than that in the survival group (8.2 ± 13.6 days). However, total hospital stays of the survival group (49.0 ± 30.6 days) were longer than that of the nonsurvival group (28.9 ± 17.8 days, P = 0.044) (Table 5).

Depending on results of tissue culture tests performed for all patients at the first surgery, NSTI was classified into 2 types. Both types I (monomicrobial infection) and II (mixed polymicrobial infection) had 14 cases (46.7%) except 2 patients with no isolated microorganism. In the group with type I, Staphylococcus aureus was the most frequent (50%) causative organism. In the group of patients with type II, the number of isolated organisms varied from 2 to 4 species, with an average of 2.3. Escherichia coli (57.1%), Streptococcus species (50%), and Anaerobes (42.8%) were predominant. However, there was no difference in mortality according to the classification (P = 0.385) (Table 6).

Hippocrates was the first to describe the NSTI in 500 BC [7]. Jones and British Army surgeons described this infection as hospital gangrene in 1871 [8]. Wilson [9] proposed the term of necrotizing fasciitis including both gas forming and nongas forming necrotizing infections in 1951, with fascial necrosis as a precondition of the infection. Recently, the term NSTI has been accepted for all anatomic locations and depths of necrotic infections because of their similarity in approaches for diagnosis and treatment [410]. NSTIs are rare, but highly lethal. Approximately 1,000 cases/yr or 0.04 cases/1,000 person-years of NSTI has been reported in the United States [11]. Unfortunately, there is no reported data on its incidence in Korea.

Microbial invasion of the soft tissues occurs either through external wound from trauma or direct spread from injured hollow viscus (particularly the lower gastrointestinal tract including the colon and rectum) or genitourinary organs. Microbial growth within the soft tissues releases a mixture of cytokines and endotoxins/exotoxins, causing the spread of infection through the superficial and deep fascia [12]. This process causes poor microcirculation and ischemia in affected tissues, ultimately leading to cell death and tissue necrosis [5].

As mentioned in the introduction, we have achieved a great improvement in the understanding of NSTI and medical or surgical intensive care. However, the mortality rate of NSTI has remained at 25% to 35%. Similarly, the overall mortality rate was 23.3% in this study.

In a retrospective cohort study, Chae et al. [13] found that underweight patients showed significantly higher mortality than normal weight patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Similarly, we confirmed that low BMI (<23 kg/m2) led to high mortality in this study. Low BMI suggests a poor nutritional status, which was thought to have influenced the immune system.

Anaya et al. [6] have revealed that WBC count > 30,000 cells/mm3, serum creatinine > 2 mg/dL, clostridial infection, and coronary artery disease at admission are independent mortality predictors for a multivariate regression analysis using 166 patients. In different reports, changes in serum levels of hematocrit, leukocyte count, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, serum sodium, potassium, magnesium, calcium, serum albumin, lactate dehydrogenase, and alkaline phosphatase are reported to be predictors for higher mortality [141516]. In this study, we can find the predictors such as chronic kidney disease requiring hemodialysis, initial WBC count > 13×103/µL, CRP > 26.5 mg/dL, PLT < 148×103/µL, high K level, BUN > 27.6 mg/dL, creatinine < 1.2 mg/dL for higher mortality.

Prompt use of empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics is essential for treatment [3]. In this study, all patients were administered broad-spectrum antibiotics within 24 hours. However, there was no statistical difference between single or combination drug regimens (P > 0.999).

Prompt surgical consultation is strongly recommended for patients with NSTI [3]. Several studies have revealed that the most important mortality factors of NSTI are the time to first surgical intervention and its adequacy [17]. Early diagnosis and intervention are essential because mortality is directly affected by time to initial intervention [17181920]. In this study, mean time from admission to operation in the survival group (159.6 ± 33.3 hours) was much longer than that in the nonsurvival group (64.3 ± 24.3 hours). This was different from the results of other studies because most patients (n = 22, 73%) were transferred from other hospitals after several hours or days of initial treatments. Therefore, the time to operation was not from the onset of symptoms but from admission. Patients operated on within 24 hours after admission in the survival group (69.6%) were slightly more than that in the nonsurvival group (57.1%). However, there was no statistical significance (P = 0.657). We also found smaller number of surgeries and shorter hospital stays in the mortality group. However, this could be interpreted as losing opportunities of treatment due to early death.

According to the Infectious Disease Society of America, NSTI was classified into 2 types [3]. Type I infections are mostly mixed polymicrobial infections having a combination of aerobes, anaerobes, and facultative aerobes/anaerobes. The common aerobic species isolated from these infections are streptococci, staphylococci, enterococci, and gram-negative rods. Bacteroides species are the most common anaerobes involved. Type II infections are usually monomicrobial infections following a minor injury. They account for 10%–15% of all NSTIs [2122]. Common organisms involved in type II infections are group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus or S. aureus. Type II can also be caused by Vibrio vulnificus, Aeromonas hydrophila, and various fungi such as Mucor, Rhizopus, or Rhizomucor [23242526]. Especially, NSTI related to Vibrio vulnificus had high mortality [27]. In this study, types I and II groups were seen in 14 patients. In the group with type I, S. aureus was the most frequent (50%) causative organism. While E. coli (57.1%), Streptococcus species (50%) and Anaerobes (42.8%) were most common organisms in the group with type II. Although there are no NSTI related to Vibrio, mortality rate in the type II group (35.7%) was higher than that in the type I group (14.3%). However, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.578).

Although appropriate antibiotics and early aggressive surgical debridement were used, NSTI showed a high mortality of 23.3%, particularly in patients with chronic kidney disease requiring hemodialysis. In addition, low BMI (<23 kg/m2) was a significant mortality factor. Initial WBC count >13×103/µL, CRP > 26.5 mg/dL, and PLT count <148×103/µL were found to negatively affect the prognosis of NSTI. Factors of potassium level, BUN >27.6 mg/dL, serum creatinine >1.2 mg/dL reflecting kidney function were significant mortality factors.

This study has several limitations. First, only 30 cases in 5 years were retrospectively reviewed. The number of patients might be too small for statistical analysis. Second, 22 patients (73%) were transferred from other hospitals. There was no information about the exact time of symptom onset or initial state. Third, patients treated in a variety of departments (surgery, thoracic surgery, urology, orthopedics, plastic surgery, internal medicine, etc.) received treatments using a variety of surgical techniques. Fourth, we can determine the factors related to mortality only in univariate analysis.

Conclusively, patients with low BMI (<23 kg/m2) or abnormal values of WBC count, CRP, and PLT count reflecting the degree of infection or abnormal renal function needed more intensive care despite several limitations.

Figures and Tables

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

These work was carried out with the support of "Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science & Technology Development (Project No. PJ01100202)" Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

This work was supported by clinical research grant from Pusan National University Hospital in 2014.

References

1. Anaya DA, Dellinger EP. Necrotizing soft-tissue infection: diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 44:705–710.

2. Altarac S, Katušin D, Crnica S, Papeš D, Rajkovic Z, Arslani N. Fournier's gangrene: etiology and outcome analysis of 41 patients. Urol Int. 2012; 88:289–293.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, Dellinger EP, Goldstein EJ, Gorbach SL, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014; 59:e10–e52.

4. Urschel JD. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. Postgrad Med J. 1999; 75:645–649.

5. Davoudian P, Flint NJ. Necrotizing fasciitis. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2012; 12:245–250.

6. Anaya DA, McMahon K, Nathens AB, Sullivan SR, Foy H, Bulger E. Predictors of mortality and limb loss in necrotizing soft tissue infections. Arch Surg. 2005; 140:151–157.

7. Descamps V, Aitken J, Lee MG. Hippocrates on necrotising fasciitis. Lancet. 1994; 344:556.

8. Jones J. Surgical memoirs of the war of the rebellion: investigation upon the nature, causes and treatment of hospital gangrene as prevailed in the Confederate armies 1861-1865. New York: US Sanitary Commission;1871.

9. Wilson B. Necrotizing fasciitis. Am Surg. 1952; 18:416–431.

10. Hussein QA, Anaya DA. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. Crit Care Clin. 2013; 29:795–806.

11. Ellis Simonsen SM, van Orman ER, Hatch BE, Jones SS, Gren LH, Hegmann KT, et al. Cellulitis incidence in a defined population. Epidemiol Infect. 2006; 134:293–299.

12. Sarani B, Strong M, Pascual J, Schwab CW. Necrotizing fasciitis: current concepts and review of the literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2009; 208:279–288.

13. Chae MK, Choi DJ, Shin TG, Jeon K, Suh GY, Sim MS, et al. Body mass index and outcomes in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. Korean J Crit Care Med. 2013; 28:266–271.

14. Chawla SN, Gallop C, Mydlo JH. Fournier's gangrene: an analysis of repeated surgical debridement. Eur Urol. 2003; 43:572–575.

15. Tuncel A, Aydin O, Tekdogan U, Nalcacioglu V, Capar Y, Atan A. Fournier's gangrene: Three years of experience with 20 patients and validity of the Fournier's Gangrene Severity Index Score. Eur Urol. 2006; 50:838–843.

16. Yeniyol CO, Suelozgen T, Arslan M, Ayder AR. Fournier's gangrene: experience with 25 patients and use of Fournier's gangrene severity index score. Urology. 2004; 64:218–222.

17. Bilton BD, Zibari GB, McMillan RW, Aultman DF, Dunn G, McDonald JC. Aggressive surgical management of necrotizing fasciitis serves to decrease mortality: a retrospective study. Am Surg. 1998; 64:397–400.

18. McHenry CR, Piotrowski JJ, Petrinic D, Malangoni MA. Determinants of mortality for necrotizing soft-tissue infections. Ann Surg. 1995; 221:558–563.

19. Voros D, Pissiotis C, Georgantas D, Katsaragakis S, Antoniou S, Papadimitriou J. Role of early and extensive surgery in the treatment of severe necrotizing soft tissue infection. Br J Surg. 1993; 80:1190–1191.

20. Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Tan JL, Low CO. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003; 85-A:1454–1460.

21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Invasive group A streptococcal infections--United Kingdom, 1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994; 43:401–402.

22. Ogilvie CM, Miclau T. Necrotizing soft tissue infections of the extremities and back. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006; 447:179–186.

23. Dechet AM, Yu PA, Koram N, Painter J. Nonfoodborne Vibrio infections: an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, 1997-2006. Clin Infect Dis. 2008; 46:970–976.

24. Mishra SP, Singh S, Gupta SK. Necrotizing soft tissue infections: surgeon's prospective. Int J Inflam. 2013; 2013:609628.

25. Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, Knudsen TA, Sarkisova TA, Schaufele RL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005; 41:634–653.

26. Yoder JS, Hlavsa MC, Craun GF, Hill V, Roberts V, Yu PA, et al. Surveillance for waterborne disease and outbreaks associated with recreational water use and other aquatic facility-associated health events--United States, 2005-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008; 57(SS09):1–29.

27. Yu SN, Kim TH, Lee EJ, Choo EJ, Jeon MH, Jung YG, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis in three university hospitals in Korea: a change in causative microorganisms and risk factors of mortality during the last decade. Infect Chemother. 2013; 45:387–393.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download