Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to determine the possible predictors of primary arteriovenous fistula (AVF) failure and examine the impact of a preoperative evaluation on AVF outcomes.

Methods

A total of 539 patients who underwent assessment for a suitable site for AVF creation by physical examination alone or additional duplex ultrasound were included in this study. Demographics, patient characteristics, and AVF outcomes were analyzed retrospectively.

Results

AVF creation was proposed in 469 patients (87.0%) according to physical examination alone (351 patients) or additional duplex ultrasound (118 patients); a prosthetic arteriovenous graft was initially placed in the remaining 70 patients (13.0%). Although the primary failure rate was significantly higher in patients assessed by duplex ultrasound (P = 0.001), ultrasound information changed the clinical plan, increasing AVF use for dialysis, in 92 of the 188 patients (48.9%) with an insufficient physical examination. Female sex and diabetes mellitus were risk factors significantly associated with primary AVF failure. Because of different inclusion criteria and a lack of adjustment for baseline differences, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed better AVF outcomes in patients assessed by physical examination alone; an insufficient physical examination was the only risk factor significantly associated with AVF outcomes.

Conclusion

Routine use of duplex ultrasound is not necessary in chronic kidney disease patients with a satisfactory physical examination. Given that female gender and diabetes mellitus are significantly associated with primary AVF failure, duplex ultrasound could be of particular benefit in these subtypes of patients without a sufficient physical examination.

Autogenous arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) are the preferred vascular access for chronic hemodialysis because of better outcomes, a lower complication rate once matured, and reduced costs compared with prosthetic arteriovenous grafts (AVGs) or central venous catheters [123456]. Nevertheless, their primary failure rates, reported to be between 10% and 50%, are quite high due to maturation failure and stenotic complications [789]. Several preoperative factors have been shown to predict the risk of primary AVF failure, primarily the diameters of the artery and vein. Comorbidities associated with primary AVF failure include advanced age, diabetes mellitus, and systemic atherosclerosis [1011]. As part of the preoperative planning, duplex ultrasound vascular mapping to assess anatomical suitability is recommended before vascular access creation for the accurate measurement of vessel diameter, and its routine use can increase the placement of an autogenous vascular access and the proportion of patients undergoing dialysis with an AVF [512]. Although duplex ultrasound plays an integral part in both the preoperative planning of AVFs and their subsequent evaluation [13], it remains to be established whether routine use of preoperative duplex ultrasound can improve AVF outcomes [14].

The aim of our present retrospective single-center study was to determine the possible predictors of primary AVF failure and examine the impact of preoperative evaluation on AVF outcomes in chronic kidney disease patients receiving hemodialysis.

This was a retrospective observational study using data extracted from medical records. The study protocol was approved by Asan Medical Center (2009-0402) Institutional Review Board. Between January 2011 and December 2012, 639 vascular access creations to enable hemodialysis were performed at our institution. Vascular surgeons physically examined the upper arm vessels in all patients referred to the vascular surgery department for the assessment of vascular access creation.

Physical examinations are deemed satisfactory for AVF creation if the following criteria were met for either the wrist or antecubital sites [715]: adequate arterial pulsatile force; adequate hand circulation according to the Allen test; a minimum external venous diameter of 2 mm in the dependent position without a tourniquet; a minimum external venous diameter of 2.5 mm in the dependent position with a tourniquet; a visible vein length of at least 5 cm and easy compressibility of this segment of the vein; absence of venous collateral circulation in the shoulder region; and absence of edema. Patients with satisfactory physical examination findings for an AVF or initial placement of an AVG had no further assessment of their vessels before surgery. Patients with an unsatisfactory physical examination underwent preoperative duplex ultrasound vascular mapping by a qualified vascular radiologist. The duplex ultrasound examination was performed without a tourniquet using a Phillips iU22 ultrasound machine (Phillips, Bothell, WA, USA) with a L15–7-MHz linear transducer. Anatomical suitability was determined using the criteria described previously [13], except that we used a minimum external venous diameter of 1.6 mm without a tourniquet as a suitable site for AVF creation. In patients suspected of having central vein stenosis, computed tomography or conventional contrast venography was used to identify an outflow obstruction.

Of the 639 patients we initially screened, we excluded 100 (15.6%) who underwent initial placement of an AVG according to physical examination alone without further assessment. The remaining 539 patients (84.4%) whose suitable site for AVF creation was assessed by physical examination alone or additional duplex ultrasound were included in this study (Fig. 1). Demographics, including potential risk factors, patient characteristics, and AVF outcomes (primary AVF failure, functional primary patency, and AVF survival), had been prospectively recorded in an Excel database (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) and were analyzed retrospectively.

The proposed site for AVF creation was the most distal site on the nondominant arm that fulfilled the criteria for vessel suitability on either physical examination alone or duplex ultrasound. The surgical procedure was performed with a side-to-end anastomosis using a 7/0 polypropylene continuous suture under local anesthesia. Postoperative surveillance was performed according to the recommendations of the clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery regarding the surgical placement and maintenance of arteriovenous hemodialysis access [2]. A last follow-up was conducted using telephone interview to evaluate AVF outcomes.

Primary AVF failure was defined as follows: an actual site of vascular access creation different from the planned site assessed by preoperative physical examination or additional duplex ultrasound, and all AVFs inadequate for dialysis after creation [16]. Functional primary patency was defined as all AVFs providing adequate dialysis for at least three dialysis sessions without further intervention, and the duration of AVF survival was the time from AVF creation to AVF failure [17].

Categorical data were analyzed by chi-square tests, and t-tests were used for interval/ordinal data. Functional primary patency and AVF survival, stratified by the assessment method (physical examination alone or duplex ultrasound), were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method, with patient follow-up censored for death, renal transplant, or transfer to a nonparticipating dialysis unit. The Cox multivariate proportional hazards regression model was used to identify independent predictors of clinical outcomes. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS ver. 18.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA), with P-values ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant.

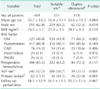

Of the 539 chronic kidney disease patients in our current study series, physical examination alone was deemed satisfactory for AVF creation in 351 patients (65.1%). In the remaining 188 patients (34.9%) with insufficient physical examination findings, additional duplex ultrasound was performed; in these patients, initial placement of an AVF was proposed in 118 patients, whereas an AVG was proposed in 70 patients (Fig. 1). Thus, in response to physical examination and additional duplex ultrasound findings, AVF creation was preoperatively proposed in 469 patients (87.0%). The demographics, characteristics, and AVF outcomes of these patients are summarized in Table 1. Because we used different inclusion criteria for AVF creation and did not adjust for baseline differences between patients with physical examination alone and patients with additional duplex ultrasound, the percentages of female gender and diabetes mellitus were significantly higher in patients assessed by duplex ultrasound (P = 0.014 and P = 0.002, respectively) and the rate of AVF creation on the most distal site was significantly higher in patients assessed by physical examination alone (P = 0.001). Although the primary failure rate was significantly higher in patients assessed by duplex ultrasound (P = 0.001), ultrasound information changed the clinical plan, increasing AVF use for dialysis, in 92 of the 188 patients (48.9%) with insufficient physical examination findings (Fig. 1).

Female gender and diabetes mellitus were the risk factors significantly associated with primary AVF failure in univariate (P = 0.001 and P = 0.006, respectively) and multivariate (P = 0.001 and P = 0.028, respectively) analyses (Table 2). The site of AVF creation and insufficient physical examination findings were not associated with primary AVF failure (Table 2). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that patients assessed by physical examination alone had significantly higher functional primary patency (P = 0.002) and AVF survival rates (P = 0.001) than patients assessed by duplex ultrasound (Fig. 2). The cumulative functional primary patency rates at 1, 2, 3, and 4 years were 84.2%, 79.6%, 73.2%, and 68.6%, respectively, in patients assessed by physical examination alone and 72.7%, 68.8%, 57.3%, and 53.8%, respectively, in patients assessed by duplex ultrasound. The cumulative AVF survival rates at 1, 2, 3, and 4 years were 89.0%, 86.3%, 83.5%, and 82.2%, respectively, in patients assessed by physical examination alone and 78.2%, 77.2%, 70.7%, and 67.3%, respectively, in patients assessed by duplex ultrasound. In the Cox analysis, after adjustment for all independent variables, insufficient physical examination findings (i.e., need for additional duplex ultrasound) was the only risk factor significantly associated with both functional primary patency and AVF survival, whereas diabetes mellitus was significantly associated with functional primary patency and female gender was significantly associated with AVF survival (Tables 3, 4).

The long-term patency of a functioning vascular access is extremely important for quality of life and longevity in chronic kidney disease patients receiving hemodialysis. The AVF is the preferred access for hemodialysis [12]. However, AVF failure has become more common because patient age is increasing and more patients have diabetes mellitus or vascular disease [14]. It is well recognized that AVFs as the access for hemodialysis are less prevalent among older patients and female patients and those with obesity, diabetes mellitus, or cardiovascular disease [18]. In addition to these preoperative risk factors, AVF failure has been attributed to the use of inadequate vessels for surgery, and the guidelines of the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative recommend routine use of ultrasound for mapping in all AVF patients while acknowledging the lack of level I evidence to support this recommendation [12].

Physical examination usually yields more information from venous than arterial assessment, whereas duplex ultrasound gives somewhat more information about the artery than the vein. Physical examination alone is insufficient in a considerable proportion of patients, and ultrasound information changes the clinical plan in a substantial number of patients who could receive an AVF rather than an AVG. In the current study, suitability for AVF creation was initially determined by physical examination. However, in patients for whom physical examination alone was not sufficient to evaluate suitable sites for AVF creation due to patient habitus and compromised vasculature, additional duplex ultrasound was performed to increase AVF use in the dialysis and to reduce unnecessary exploration; we found that physical examination alone was insufficient in 34.9% and that duplex ultrasound made a relevant contribution to 48.9% of these patients.

Duplex ultrasound is a noninvasive, effective, and safe method for establishing morphologic and functional parameters or characteristics of vessels that could help surgeons to improve AVF maturation rates [19]. It can identify suitable veins that cannot be determined by physical examination alone [19]. In recent years, some authors have recommended the routine use of duplex ultrasound prior to AVF creation. Others, however, have found no evidence that duplex ultrasound decreases AVF failure rates, providing evidence that selected patients with insufficient physical examination benefit from duplex ultrasound while duplex ultrasound is not needed when adequate vessels are defined by physical examination [1520]. There is no general consensus on the role of duplex ultrasound prior to AVF creation, and controversy persists regarding the optimal criteria of a suitable site for AVF on duplex ultrasound. Although some authors reported that vein size is the major predictor of a successful AVF [2122], the optimal preoperative venous diameter for AVF creation has not been validated in prospective randomized trials. In our present study, we used a different cutoff of minimum venous diameter proposed for initial placement of an AVF between patients assessed by physical examination alone and patients assessed by additional duplex ultrasound. We remained aggressive in attempting to place an AVF in all suitable patients, and additional duplex ultrasound was performed in patients with unsatisfactory physical examination, using a minimum external venous diameter of 1.6 mm without a tourniquet as a suitable site for AVF creation. This difference resulted in a higher primary failure rate in patients assessed by duplex ultrasound, but ultrasound information changed the clinical plan, increasing AVF use for dialysis, in patients with unsatisfactory physical examination findings.

Different outcomes of AVF have been used in previous studies examining the effect of preoperative evaluation [14]. In our current study, we evaluated AVF outcomes using primary AVF failure, functional primary patency, and AVF survival. Primary AVF failure considers all AVFs that remain inadequate for dialysis after creation [16]. Because primary failure can take account of AVFs in patients not already on dialysis, it is probably the best measure for assessing the effect of preoperative evaluation on AVF outcomes [14]. The aim of our present study was to examine the impact of preoperative evaluation on AVF outcomes in patients who require an AVF. Therefore, we modified the definition of primary AVF failure to an actual site of vascular access creation different from the planned site assessed by preoperative physical examination or duplex ultrasound, in addition to all AVFs remaining inadequate for dialysis after creation, and found that female gender and diabetes mellitus were significantly associated with primary AVF failure.

We acknowledge that our study had several limitations. Although there are definite criteria of anatomical suitability for AVF creation in our institution, this was a retrospective review that relied on available patient information and it was thus vulnerable to insufficient data availability and accuracy. Patients were selected for initial placement of an AVF according to physical examination findings and additional use of duplex ultrasound was also determined based on initial physical examination findings, suggesting a possible selection bias. Furthermore, our definitions of AVF outcomes were limited to our clinical assessment after an AVF placement. Finally, our current findings were obtained from at a single center, resulting in a small sample size and a short study period that limited the overall relevance of our results.

Despite these potential limitations, we found that chronic kidney disease patients assessed by physical examination alone had significantly better AVF outcomes, and insufficient physical examination, as judged by the need for additional duplex ultrasound, was the only risk factor significantly associated with both functional primary patency and AVF survival. Duplex ultrasound information could increase AVF use in dialysis and reduce unnecessary exploration in such patients with insufficient physical examination findings.

In conclusion, routine use of duplex ultrasound is not necessary in chronic kidney disease patients with satisfactory physical examination findings. Given that female gender and diabetes mellitus were significantly associated with primary AVF failure, duplex ultrasound could be of particular benefit in these specific patients who have an insufficient physical examination. Future prospective trials with larger cohorts will lead to a better understanding of the role of preoperative duplex ultrasound in chronic kidney disease patients receiving hemodialysis.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Flow chart of patient inclusion and the management protocol. Values in parentheses are the number of patients. AVF, arteriovenous fistula; AVG, arteriovenous graft.

Fig. 2

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of patients undergoing AVF creation (including maturation failure). Cumulative functional primary patency (A) and cumulative AVF survival (B) between patients assessed by physical examination alone and patients additionally assessed by duplex ultrasound. AVF, arteriovenous fistula.

Table 1

Demographics, clinical characteristics, and outcomes in chronic kidney disease patients undergoing AVF creation

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%). AVF, arteriovenous fistula; BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; CAD, coronary artery disease; PAOD, peripheral arterial occlusive disease.

a)Physical examination alone was deemed satisfactory for AVF creation. b)Duplex ultrasound was performed because of insufficient physical examination findings. c)The most distal site (wrist) on the nondominant arm. d)Defined as an actual site of vascular access creation different from the planned site and all AVFs remaining inadequate for dialysis after creation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Green Cross Pharma Group (grant number: 2009-0402).

References

1. Dageforde LA, Harms KA, Feurer ID, Shaffer D. Increased minimum vein diameter on preoperative mapping with duplex ultrasound is associated with arteriovenous fistula maturation and secondary patency. J Vasc Surg. 2015; 61:170–176.

2. Sidawy AN, Spergel LM, Besarab A, Allon M, Jennings WC, Padberg FT Jr, et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery: clinical practice guidelines for the surgical placement and maintenance of arteriovenous hemodialysis access. J Vasc Surg. 2008; 48:5 Suppl. 2S–25S.

3. Rooijens PP, Tordoir JH, Stijnen T, Burgmans JP, Smet de AA, Yo TI. Radiocephalic wrist arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis: meta-analysis indicates a high primary failure rate. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004; 28:583–589.

4. Long B, Brichart N, Lermusiaux P, Turmel-Rodrigues L, Artru B, Boutin JM, et al. Management of perianastomotic stenosis of direct wrist autogenous radial-cephalic arteriovenous accesses for dialysis. J Vasc Surg. 2011; 53:108–114.

5. Saucy F, Haesler E, Haller C, Déglise S, Teta D, Corpataux JM. Is intra-operative blood flow predictive for early failure of radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010; 25:862–867.

6. Song D, Yun S, Cho S. Posterior triangle approach for lateral in-plane technique during hemodialysis catheter insertion via the internal jugular vein. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2015; 88:114–117.

7. Smith GE, Barnes R, Chetter IC. Randomized clinical trial of selective versus routine preoperative duplex ultrasound imaging before arteriovenous fistula surgery. Br J Surg. 2014; 101:469–474.

8. Ravani P, Spergel LM, Asif A, Roy-Chaudhury P, Besarab A. Clinical epidemiology of arteriovenous fistula in 2007. J Nephrol. 2007; 20:141–149.

9. Maya ID, O'Neal JC, Young CJ, Barker-Finkel J, Allon M. Outcomes of brachiocephalic fistulas, transposed brachiobasilic fistulas, and upper arm grafts. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009; 4:86–92.

10. Ortega T, Ortega F, Diaz-Corte C, Rebollo P, Ma Baltar J, Alvarez-Grande J. The timely construction of arteriovenous fistulae: a key to reducing morbidity and mortality and to improving cost management. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005; 20:598–603.

11. Lin YP, Wu MH, Ng YY, Lee RC, Liou JK, Yang WC, et al. Spiral computed tomographic angiography--a new technique for evaluation of vascular access in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 1998; 18:117–122.

12. National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI Clinical practice guidelines and clinical practice recommendations for 2006 updates: hemodialysis adequacy, peritoneal dialysis adequacy and vascular access. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006; 48:Suppl 1. S1–S322.

13. Kerr SF, Krishan S, Lapham RC, Weston MJ. Duplex sonography in the planning and evaluation of arteriovenous fistulae for haemodialysis. Clin Radiol. 2010; 65:744–749.

14. Ferring M, Henderson J, Wilmink A, Smith S. Vascular ultrasound for the preoperative evaluation prior to arteriovenous fistula formation for haemodialysis: review of the evidence. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008; 23:1809–1815.

15. Nursal TZ, Oguzkurt L, Tercan F, Torer N, Noyan T, Karakayali H, et al. Is routine preoperative ultrasonographic mapping for arteriovenous fistula creation necessary in patients with favorable physical examination findings? Results of a randomized controlled trial. World J Surg. 2006; 30:1100–1107.

16. Allon M, Robbin ML. Increasing arteriovenous fistulas in hemodialysis patients: problems and solutions. Kidney Int. 2002; 62:1109–1124.

17. Lockhart ME, Robbin ML, Fineberg NS, Wells CG, Allon M. Cephalic vein measurement before forearm fistula creation: does use of a tourniquet to meet the venous diameter threshold increase the number of usable fistulas? J Ultrasound Med. 2006; 25:1541–1545.

18. Pisoni RL, Young EW, Dykstra DM, Greenwood RN, Hecking E, Gillespie B, et al. Vascular access use in Europe and the United States: results from the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2002; 61:305–316.

19. Wong CS, McNicholas N, Healy D, Clarke-Moloney M, Coffey JC, Grace PA, et al. A systematic review of preoperative duplex ultrasonography and arteriovenous fistula formation. J Vasc Surg. 2013; 57:1129–1133.

20. Wells AC, Fernando B, Butler A, Huguet E, Bradley JA, Pettigrew GJ. Selective use of ultrasonographic vascular mapping in the assessment of patients before haemodialysis access surgery. Br J Surg. 2005; 92:1439–1443.

21. Lauvao LS, Ihnat DM, Goshima KR, Chavez L, Gruessner AC, Mills JL Sr. Vein diameter is the major predictor of fistula maturation. J Vasc Surg. 2009; 49:1499–1504.

22. Mendes RR, Farber MA, Marston WA, Dinwiddie LC, Keagy BA, Burnham SJ. Prediction of wrist arteriovenous fistula maturation with preoperative vein mapping with ultrasonography. J Vasc Surg. 2002; 36:460–463.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download