Abstract

Purpose

In about 1% of cases, incidental gallbladder cancers (iGBC) are found after routine cholecystectomy. The aim of this study is to compare clinical features of iGBC with benign GB disease and to evaluate factors affecting recurrence and survival.

Methods

Between January 1998 and March 2014, 4,629 patients received cholecystectomy and 73 iGBC patients (1.6%) were identified. We compared clinical features of 4,556 benign GB disease patients with 73 iGBC patients, and evaluated operative outcomes and prognostic factors in 56 eligible patients.

Results

The iGBC patients were older and concomitant diseases such as hypertension and anemia were more common than benign ones. And an age of more than 65 years was the only risk factor of iGBC. Adverse prognostic factors affecting patients' survival were age over 65, advanced histology, lymph node metastasis, and lymphovascular invasion on multivariate analysis. Age over 65 years, lymph node involvement, and lymphovascular invasion were identified as unfavorable factors affecting survival in subgroup analysis of extended cholecystectomy with bile duct resection (EC with BDR, n = 22).

Gallbladder (GB) cancer is the fifth most common malignancy of the gastrointestinal tract, with an incidence of 0.8%–1.2%, and is the most common malignancy of the biliary tract [1]. Occasionally, GB malignancy is found on pathologic reports after routine cholecystectomy. Recent studies have reported an increase in incidental GB cancer (iGBC), with approximately 50%–58% of all new GBC cases [23]. Some authors have reported incidence of iGBC after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) was approximately 0.2%–2.1% [456].

When iGBC is detected after cholecystectomy, additional procedures such as liver resection, lymph node dissection, and/or bile duct resection (BDR) may be performed depending on pathologic and imaging findings. Glenn and Hays [7] first introduced 'radical cholecystectomy' (Glenn operation), a radical resection technique with regional lymphadenectomy. Pack et al. [8] and Fahim et al. [9] have also reported combined hepatectomy and portal lymph node dissection in pT1b or more advanced GBC.

In general, it is difficult to anticipate GB malignancy in most routine cholecystectomies for preoperative diagnosis of benign GB diseases. Additionally, surgeons often encounter the concerns of tumor spread in perioperative GB perforation and of reoperation extent. To date, there have been few reports on the predictive factors of iGBC. A recently published article described old age, female gender, Asian or African American, elevated serum ALP and conversion to open cholecystectomy as risk factors in LC patients [10].

In this retrospective study, we reviewed the clinicopathological characteristics of iGBC compared with benign GB diseases and sought to find predictive risk factors. We also analyzed prognostic factors affecting recurrence and survival in iGBC patients.

In our institution, 4,629 patients received cholecystectomy between January 1998 and March 2014. Seventy-three patients (1.6%) were confirmed to have iGBC on final pathology. Demographics and clinical characteristics of these patients were retrospectively retrieved and were compared to those of 4,556 benign patients. For continuous variables, Student t-test was used for comparisons. Categorical variables were analyzed with the chi-square test or Fisher exact test. And multiple logistic regression models for a dichotomous outcome were developed, and odds ratios were utilized to evaluate preoperative iGBC risk factors.

Seventeen patients were excluded from further survival analysis: 8 due to confirmed metastasis or seeding during operation; 4 were lost to follow up; and 5 as a result of death by other diseases (3 cases of primary lung cancer, 1 acute myocardial infarction, 1 brain infarction) (Fig. 1). Disease-free and overall survival (OS) was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Prognostic factors were analyzed by the univariate Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test to identify the predictors for survival. Multivariate regression analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model to identify the independent prognostic factors for survival. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All Statistical calculations were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 19.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

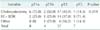

A total of 73 patients were identified as iGBC cases and the other 4,556 were benign GB diseases. The mean age of iGBC patients was older than that of benign ones (68.4 ± 11.5 years vs. 57.7 ± 15.8 years, P = 0.001). The hemoglobin levels differed significantly between the two groups (iGBC vs. benign, 12.5 ± 1.7 g/dL vs. 13.2 ± 1.9 g/dL; P = 0.007). But levels of total bilirubin, AST, ALT, ALP, WBC, and platelet counts were not significantly different. In addition, more iGBC patients were on antihypertensive medications (P = 0.047) (Table 1).

Among the 73 cancer patients, 32 (43.8%) were men and 50 (68.5%) had preceding gastrointestinal symptoms. Preoperative diagnoses were diverse: 22 symptomatic GB stones (30.1%), 23 acute cholecystitis (31.5%), 17 GB polyps (23.3%), 6 GB empyema (8.2%), 3 GB polypoid mass (4.1%), 1 combined GB stone and polyp (1.4%), and 1 choledochal cyst (1.4%). Multiple logistic regression analysis identified that only an age more than 65 years was significantly associated with iGBC (odds ratio, 2.542; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.352–4.777; P = 0.004).

Fifty-six eligible patients underwent different operations for iGBC according to pathologic and imaging findings (Table 2). The most common curative reoperation for advanced GBC was EC with BDR. We defined EC as cholecystectomy including wedge resection of the GB fossa with a rim of normal hepatic tissue (approximately 2 cm in thickness or more), or segmentectomy of liver segments (IVb and V) with regional lymph node dissection. EC after primary cholecystectomy was usually performed for (1) pT2 or pT3, (2) suspicious lymph node enlargement on postoperative CT scan, and (3) positive cystic duct resection margin. And BDR was considered in situations of (2) and (3) in our institution. In fact, additional surgical procedures were not strictly protocol-driven and eighteen patients received only cholecystectomy because of patient refusal, comorbid medical conditions and so on.

Univariate analysis revealed that older age (≥65 years), higher serum level of CA 19-9 (≥50 U/mL), acute cholecystitis, and GB empyema on preoperative diagnosis were adverse clinical factors of recurrence and survival. Also, in perioperative GB perforation subset, early recurrence was significantly greater and their 6-month, 1-year, and 3-year DFS rates compared with nonperforation group were 58% vs. 79%; 44% vs. 65%; and 36% vs. 59%, respectively (P = 0.04). However, OS was not significantly different between perforation and nonperforation subgroups (Table 3). In a subgroup analysis of EC with BDR (n = 22), GB perforation was not statistically significant in DFS (P = 0.127) and OS (P = 0.113). And advanced pT stage, advanced pN stage, positive resection margin, moderate or poor differentiation, positive perineural invasion, and positive lymphovascular invasion were also risk factors of recurrence and survival on univariate analysis. However, tumor size and types of operation did not affect patients' outcome (Table 4, Fig. 2). In subgroup analysis for those who received EC with BDR (n = 22), cumulative OS curves based on pathologic T staging and pathologic N staging are respectively shown (Fig. 3A, B).

On a multivariate analysis of all iGBC patients, age more than 65 years, positive lymph node, moderately or poorly differentiated tumor, and presence of lymphovascular invasion were statistically significant predictors of poor prognosis. But in EC with BDR subgroup analysis, elderly age (hazard ratio [HR], 107.7; 95% CI, 2.812–4,132.1; P = 0.012), lymph node involvement (HR, 10.88; 95% CI, 1.004–117.9; P = 0.049), lymphovascular invasion (HR, 33.62; 95% CI, 2.444–462.401; P = 0.009) were identified as adverse prognostic factors. Depth of tumor (T-stage), however, was not a significant prognostic factor in both all-iGBC patients group and EC with BDR subgroup (Table 5).

Cholecystectomy is one of the most commonly performed surgical treatments around the world. As the safety and feasibility of LC have been demonstrated, it is being performed with increasing frequency even in elderly patients [11]. And technical advances in ultrasonography and computed tomography have contributed to earlier detection of GB cancer, preoperatively. Still, incidental GB malignancy is reported in 0.2%–2.1% of all routine cholecystectomy for benign GB diseases [456]. In our cohort, seventy-three (1.57%) iGBC cases were verified.

The importance of preoperative suspicion of malignancy cannot be emphasized enough. Prior to surgery, patients at an increased risk for iGBC need to be identifiable in clinical practice. Even though several GBC risk factors have been proposed, many of them are based on epidemiology, image findings, or small size of cohorts in advanced tumors. Unfortunately, few reports on predictors of iGBC are available in the English literature until now. Some investigators suggested iGBC was more likely found in elderly patients, dilated bile duct, and thickened GB wall [12]. Another retrospective study revealed that advanced age, female sex, Asian or African American ethnicity, an elevated ALP, and converted open cholecystectomy as risk factors [10]. We found that iGBC patients tend to be older, anemic, and on hypertensive medication compared with benign GB diseases. But an age 65 years or older was the only independent predictor in our study. In the literature review, an advanced age has been consistently a major risk for iGBC but there is no consensus on the other factors. This is because incidence of iGBC is relatively rare, thus most studies are retrospective in study design. Also, sensitivity and specificity of imaging modalities can be inaccurate to forecast tumorous conditions, especially in severe cholecystitis or empyema accompanied by GB wall thickening.

The prognosis of GB cancer is poor and large studies have shown only 2.7%–15% 5-year OS rate in advanced stages [1314]. Many prognostic factors have been reported and the depth of tumor and lymph node metastasis remain the best among GBC experts [13141516]. Recently, a Japanese multicenter study determined that age ≥70 years, female sex, tumor stage, and operative procedures were independent prognostic factors [16]. Nevertheless, little evidence is available regarding survival outcome of unsuspected GB malignancy. And it is not clear whether iGBC patients have a better or similar prognosis when compared with the same stage of nonincidental cases. In a meta-analysis, conversion to radical surgery warranted a survival benefit in pT2 or more advanced iGBC, although additional surgical procedures were not uniform [17].

A comprehensive decision of subsequent radical surgery is the most important clinical issue for both surgeons and patients. In our study, reoperations were not always protocoldriven for various reasons. Seventeen pT2 patients and one pT3 received only cholecystectomy. Because of advanced age (median, 75 years) and concomitant comorbidities, 16 of them refused reoperations. Another 2 patients were on palliative chemotherapy for other primary malignancies. Since data from these exceptive patients can cause a selection bias, we did further subgroup analysis on patients who received following EC with BDR. In addition, 2 pT1a patients were included; 1 patient with lymph node enlargement on postoperative CT scan and the other with positive cystic duct resection margin.

The types of operation did not influence the all-iGBC patients' survival. This finding was probably confounded by nodal status. First, reoperations for pT2 or more advanced were not routinely performed as mentioned above, so patients with positive lymph node could have been included in cholecystectomy only group. Second, even in patients who received EC with BDR, survival outcomes were strongly affected by the presence of node metastasis. Our study demonstrated age ≥65 years, positive lymph node, and lymphovascular invasion were independent prognostic factors for survival in EC with BDR subgroup. Differentiation of tumor played a prognostic role in our preliminary analysis and in other studies [1819], but was not statistically significant in EC with BDR patients. Unlike a Chinese study [4], tumor depth was not correlated with survival in our cohorts. These incoherent results from previous reports and our study may originate from the inevitable limitations of retrospective analysis for the relatively small and heterogeneous population. Even though our result is based on a small number of patients, findings from the homogeneous EC with BDR subgroup can provide clinicians with background information for future clinical trials.

Many authors reported that perforated GB during surgery is a prognostic factor for recurrence or survival [2021222324]. Ouchi et al. [22] mentioned that GB perforation during LC was up to 20% of patients, and the incidence was irrespective of depth of cancer invasion. In our study, intraoperative perforation was noted in 17 out of 56 (30.4%). Perforation was frequently observed in preoperative diagnoses of cholecystitis (6 of 16, 37.5%) and empyema (4 of 5, 80%); and 10 perforated patients (58.8%) received only cholecystectomy because of patient refusal and other reasons. To control a selection bias, we performed subgroup (EC with BDR) analysis wherein perforation (n = 5) did not affect recurrence (P = 0.127) and OS (P = 0.113) in our study. However, in cases of preoperatively assumed severe cholecystitis or GB empyema, surgical procedures need to be performed with caution, if possible, to avoid GB perforation.

Our study has some limitations. First, the number of the iGBC patients was relatively small, hence this study was designed in a retrospective manner. Second, surgical procedures were not always protocol-driven for various clinical reasons. Therefore, a large multicenter study should be conducted to overcome the limitations of our findings.

In summary, iGBC should be preoperatively suspected, especially in old-aged patients. An age older than 65 years, lymph node metastasis, and lymphovascular invasion are important prognostic factors in iGBC patients who received subsequent EC with BDR.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Selection process of patients with incidentally confirmed gallbladder cancer (n = 56). GB, gallbladder; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CVA, cerebral vascular accident.

Fig. 2

Kaplan-Meier survival curves according to types of operation in all cancer patients (n = 56). EC, extended cholecystectomy; BDR, bile duct resection.

Fig. 3

Kaplan-Meier survival curves according to pathologic T (A) and pathologic N (B) stages in extended cholecystectomy with bile duct resection subgroup (n = 22).

Table 3

Clinical prognostic factors of recurrence and survival in patients with incidental gallbladder cancer (n = 56)

References

1. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C, et al. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006; 56:106–130.

2. Butte JM, Matsuo K, Gonen M, D'Angelica MI, Waugh E, Allen PJ, et al. Gallbladder cancer: differences in presentation, surgical treatment, and survival in patients treated at centers in three countries. J Am Coll Surg. 2011; 212:50–61.

3. Shih SP, Schulick RD, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, Choti MA, et al. Gallbladder cancer: the role of laparoscopy and radical resection. Ann Surg. 2007; 245:893–901.

4. Zhang WJ, Xu GF, Zou XP, Wang WB, Yu JC, Wu GZ, et al. Incidental gallbladder carcinoma diagnosed during or after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 2009; 33:2651–2656.

5. Yamamoto H, Hayakawa N, Kitagawa Y, Katohno Y, Sasaya T, Takara D, et al. Unsuspected gallbladder carcinoma after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005; 12:391–398.

6. Kwon AH, Imamura A, Kitade H, Kamiyama Y. Unsuspected gallbladder cancer diagnosed during or after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2008; 97:241–245.

7. Glenn F, Hays DM. The scope of radical surgery in the treatment of malignant tumors of the extrahepatic biliary tract. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1954; 99:529–541.

8. Pack GT, Miller TR, BrasfielD RD. Total right hepatic lobectomy for cancer of the gallbladder; report of three cases. Ann Surg. 1955; 142:6–16.

9. Fahim RB, McDonald JR, Richards JC, Ferris DO. Carcinoma of the gallbladder: a study of its modes of spread. Ann Surg. 1962; 156:114–124.

10. Pitt SC, Jin LX, Hall BL, Strasberg SM, Pitt HA. Incidental gallbladder cancer at cholecystectomy: when should the surgeon be suspicious? Ann Surg. 2014; 260:128–133.

11. Lee SI, Na BG, Yoo YS, Mun SP, Choi NK. Clinical outcome for laparoscopic cholecystectomy in extremely elderly patients. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2015; 88:145–151.

12. Koshenkov VP, Koru-Sengul T, Franceschi D, Dipasco PJ, Rodgers SE. Predictors of incidental gallbladder cancer in patients undergoing cholecystectomy for benign gallbladder disease. J Surg Oncol. 2013; 107:118–123.

13. Manfredi S, Benhamiche AM, Isambert N, Prost P, Jouve JL, Faivre J. Trends in incidence and management of gallbladder carcinoma: a population-based study in France. Cancer. 2000; 89:757–762.

14. Donohue JH. Present status of the diagnosis and treatment of gallbladder carcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001; 8:530–534.

15. Donohue JH, Stewart AK, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on carcinoma of the gallbladder, 1989-1995. Cancer. 1998; 83:2618–2628.

16. Kayahara M, Nagakawa T, Nakagawara H, Kitagawa H, Ohta T. Prognostic factors for gallbladder cancer in Japan. Ann Surg. 2008; 248:807–814.

17. Choi KS, Choi SB, Park P, Kim WB, Choi SY. Clinical characteristics of incidental or unsuspected gallbladder cancers diagnosed during or after cholecystectomy: a systematic review and metaanalysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015; 21:1315–1323.

18. Mazer LM, Losada HF, Chaudhry RM, Velazquez-Ramirez GA, Donohue JH, Kooby DA, et al. Tumor characteristics and survival analysis of incidental versus suspected gallbladder carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012; 16:1311–1317.

19. Choi SB, Han HJ, Kim CY, Kim WB, Song TJ, Suh SO, et al. Incidental gallbladder cancer diagnosed following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 2009; 33:2657–2663.

20. Z'graggen K, Birrer S, Maurer CA, Wehrli H, Klaiber C, Baer HU. Incidence of port site recurrence after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for preoperatively unsuspected gallbladder carcinoma. Surgery. 1998; 124:831–838.

21. Lundberg O. Port site metastases after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Eur J Surg Suppl. 2000; (585):27–30.

22. Ouchi K, Mikuni J, Kakugawa Y. Organizing Committee. The 30th Annual Congress of the Japanese Society of Biliary Surgery. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for gallbladder carcinoma: results of a Japanese survey of 498 patients. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002; 9:256–260.

23. Suzuki K, Kimura T, Ogawa H. Is laparoscopic cholecystectomy hazardous for gallbladder cancer? Surgery. 1998; 123:311–314.

24. Yamaguchi K, Chijiiwa K, Ichimiya H, Sada M, Kawakami K, Nishikata F, et al. Gallbladder carcinoma in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Arch Surg. 1996; 131:981–984.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download