Abstract

Purpose

The oncologic outcomes after performing laparoscopic surgery (LS) compared to open surgery (OS) are still under debate and a concern when treating patients with colon cancer. The aim of this study was to compare the long-term oncologic outcomes of LS and OS as treatment for stage III colorectal cancer patients.

Methods

From January 2001 to December 2007, 230 patients with stage III colorectal cancer who had undergone LS or OS in this single center were assessed. Data were analyzed according to intention-to-treat. The primary endpoints were disease-free survival and overall survival.

Results

A total of 230 patients were entered into the study (114 patients had colon cancer-33 underwent LS and 81 underwent OS; 116 patients had rectal cancer-44 underwent LS and 72 underwent OS). The median follow-up periods for the colon and rectal cancer groups were 54 and 53 months, respectively. The overall conversion rate was 12.1% (n = 4) for colon cancer, and 4.5% (n = 2) for rectal cancer. Disease-free 5-year survival of colon cancer was 84.3% and 90% in LS group (LG) and OS group (OG), respectively, and that of rectal cancer was 83% and 74.6%, respectively (P > 0.05). Overall 5-year survival for colon cancer was 72.2% and 71.3% for LG and OG, respectively, and that for rectal cancer was 67.6% and 59.2%, respectively (P > 0.05).

Laparoscopic colectomy for colon cancer is now considered an acceptable alternative to conventional open colectomy based on multicenter prospective randomized studies [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Those studies presented the safety and efficacy of the laparoscopic approach for both colon and rectal cancer. However, few randomized controlled trials in the literature have evaluated the oncologic outcomes after laparoscopic surgery (LS) when compared with open surgery (OS) for rectal cancer [8,11,12]. Therefore, the present role of LS for the treatment of rectal cancer, compared to colon cancer, remains controversial as findings are based on very few large-scale randomized trials.

Most of the major randomized studies showed similar oncologic outcomes of LS and compared to OS for colorectal cancer. Only the random trial performed by Lacy et al. [4] indicated excellent long-term oncologic results following LS, when compared with OS in patients with curable colon cancer. This study had a median follow-up of 95 months, but the difference between the two techniques was only due to the improvement in the survival of patients with stage III colon cancer.

The oncologic outcomes after performing LS instead of OS are still under debate and a concern when treating patients with colon cancer. No study has yet reported better oncologic outcomes after LS when compared with OS for the treatment of rectal cancer. The aim of the present study was therefore to compare the long-term oncologic outcomes-including recurrences and disease-free and overall survivals-following LS versus OS for stage III colorectal cancer.

From January 2001 to December 2007, we evaluated all patients who had undergone colorectal cancer surgery and who were diagnosed with TNM stage III colorectal cancer. We excluded multiple primary tumors of the colorectum, hereditary disease, and emergency cases such as bowel obstruction or perforation due to colorectal cancer. In total, 230 patients were enrolled in this study: 77 patients underwent LS and 153 patients underwent OS. All operations were performed by two surgeons in a single center. All relevant data were entered in a prospectively maintained database and reviewed by the authors for verification.

Both LS and OS for colorectal cancer was performed by two surgeons with wide experience in LS. All LS and OS were performed according to oncologic principles. The first 30 LS for colon or rectal cancer performed by each surgeon were excluded to avoid the potential bias of a steep learning curve in our institute. Exclusion criteria of LS for colorectal cancer were as follows: those with (1) large sized tumor more than 10 cm, (2) preoperative evidence of invasion of adjacent structure, (clinically T4 colorectal cancer) (3) contraindication to general anesthesia under pneumoperitoneum.

Medial to lateral dissection of the mesocolon in LS group (LG) for colon cancer, and lateral to medial approach in OS group (OG) were carried out. In cases of rectal cancer, a medial to lateral approach was performed for both techniques. A total mesorectal excision was used for rectal cancer as the standard surgical procedure. Lymph nodes were obtained by the use of gross examination and manual palpation, and were evaluated after staining with hematoxylin and eosin.

We divided and analyzed the cases into colon cancer and rectal cancer. We assessed the underlying disease, operative history, neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy, postoperative recovery, morbidity, mortality, recurrence, disease free survival, and overall survival in each group. We evaluated postoperative recovery by investigating the time of first passage of gas, the first time consuming a soft diet, and the total days in the hospital. Postoperative mortality was defined as 30-day or inhospital mortality. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for stage III rectal cancer was not routinely advocated in our department and indicated only to low-lying clinical T4 tumor. Adjuvant chemotherapy following surgery was offered to all medically fit patients according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.

All patients were followed up every 2-3 months for the first 3 years, every 6 months until 5 years, and annually thereafter. A clinical examination, serum carcinoembryonic antigen level measurement, and chest x-ray were performed at each follow-up visit. Abdominopelvic CT scans were performed annually. A colonoscopy, chest CT, pelvic MRI, or 18-fluorodeoxyglucose-PET scan was performed as indicated according to the surgeon's direction.

Recurrence was evaluated on the basis of physical, radiological and biopsy results. Survival was calculated from the date of surgery to the last visit or death. Disease-free survival was calculated from the first day of treatment to the date on which disease progression was first documented or at the last follow-up.

Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation. Data between groups were analyzed with independent t-test or chi-square test. Survivals were assessed by the Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank test. For all tests, a P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gachon University Gil Medical Center.

A total of 230 patients were entered for the study. Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of the 230 patients analyzed. No differences were noted between the LG and OG with respect to gender, age, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, associated disease, and type of operation. More patients had undergone previous operations in the OG (27.2%, n = 22) than in the LG (9.1%, n = 3) for colon cancer (P = 0.018). The left-sided colon cancer was more prevalent in the OG than in the LG. The number of patients with lower rectal cancer was higher in the OG than that in the LG. The majority of tumors were located in mid or lower rectum: 31/44 (70.5%) and 61/72 (84.7%) in LG and OG, respectively. Postoperative chemoradiation therapy following rectal surgery was given to the mid to lower rectal cancer patients: 27/31 (87.1%) and 54/61 (88.5%) in LG and OG, respectively.

Postoperative outcomes are listed in Table 2. The overall conversion rate was 12.1% (n = 4) for colon cancer, and 4.5% (n = 2) for rectal cancer. The reasons for conversion in laparoscopic colon surgery were invasion to adjacent organs in 2 patients, a huge fixed tumor in 1 patient, and intraoperative bleeding in 1 patient. Two cases were converted to the open technique due to invasion to organs and a fixed status of the cancer in LG of rectal cancer. Operation time was longer for LG than for OG for rectal cancer. Time to pass the first flatus, time to start the first soft diet, and postoperative hospital stay showed no significant differences between the two groups. The rate of diversion formation in rectal cancer was 24.2% (n = 8) and 32.7% (n = 18) in the LG and OG, respectively. The performance of adjuvant chemotherapy after colon and rectal surgery did not differ in the two groups. The overall morbidity in the colon cancer group was similar in both groups. The morbidity following rectal surgery was 25% (n = 11), 16.7% (n = 12) in LS and OS, respectively (P = 0.171). Ileus was more common in the OG (n = 7), and postoperative leakage was the most common complication in the LG (n = 5) of rectal cancer. No deaths occurred within 30 days in either group.

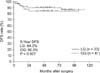

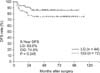

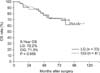

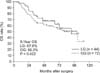

The median follow-up for our study was 54 months for colon cancer and 53 months for rectal cancer. There were no port site or specimen-extraction site recurrence after LS or OS. Overall recurrence rate for colon cancer was 15.2% (n = 5) and 11.1% (n = 9) in the LG and OG, respectively. The recurrence rate for rectal cancer was 13.6% (n = 6) in the LG and 23.6% (n = 17) in the OG (Table 3). There was no difference in local recurrence rate for right colon cancer between two groups, and same as for left colon cancer (P > 0.05). Disease-free survival rate at five years was 84.3% and 90.0% in the LG and OG, respectively, for colon cancer (Fig. 1), and 83.0% and 74.6% for rectal cancer (P > 0.05) (Fig. 2). Overall five-year survival rate was 72.2% and 71.3% in the LG and OG for colon cancer (Fig. 3), and 67.6% and 59.2% for rectal cancer, respectively (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Since we reported the mid-term results of LS and OS for nonmetastatic colorectal cancer [13], we need greater numbers of long-term follow-up results for colorectal cancer, especially at stage III. Therefore, we conducted a single center nonrandomized study to evaluate the long-term oncologic outcomes of LS versus OS for stage III colon and rectal cancer patients. Even though this study was performed retrospectively, the data were collected from a prospective clinicopathological database initiated in 2001. For this reason, we deemed the accuracy of these data to be high, as indicated by the substantial rate of follow-up. The current study has some limitations, such as its small size and nonrandomized design. The present study was also limited by its retrospective and nonrandomized design. Nonetheless, we could not randomize the patients because of patient's refusal and ethical concerns about the safety of the LS at that time. On the basis of data of tumor location, the patients with colorectal cancer were not equally distributed in the group of LS and OS.

While LS entails a steep learning curve for the surgeon, the operative time for colon cancer was similar in both groups. The duration of operation for rectal cancer was significantly shorter for OS than for LS. These results suggest that LS for rectal cancer, especially advanced cancer, may require a steeper learning curve than for colon cancer. In our study, anastomotic leakage occurred in 5 of 44 rectal cancer patients (11.3%) in the LG. Even though we excluded the first 30 LS for colorectal cancer to avoid the potential bias of a steep learning curve, the majority of leaked patients was developed in the early phase of our study. The patients were managed using a minimally invasive technique including laparoscopic saline irrigation and diverting loop ileostomy through a right lower quadrant trocar site. Reapproach of a minimally invasive surgery can be an important advantage when a patient underwent minimally invasive surgery was in face of surgical complication. The rate of 11.3% was comparable to the 0.5% to 17% rate reported in laparoscopic series [11,13,14,15,16].

In our study, the overall conversion rate of laparoscopic colon and rectal surgery was 12.1% and 4.5%, respectively. Conversions from a laparoscopic technique to an open technique were more common in patients with colon cancer. Conversion rates in multicenter trial for laparoscopic colon-cancer surgery were reported to range from 19% to 25% [1,5,7]. The low conversion rate in our laparoscopic rectal surgery compares favorably with a conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in colorectal cancer (CLASICC) trial that showed a conversion rate of up to 34% [7]. The most common causes for conversion in colorectal cancer were invasiveness and excessive tumor fixity [1,5,7]. Likewise, the main reasons for conversion in laparoscopic colorectal surgery in our study were invasion to adjacent organs and a huge fixed tumor. The causes for conversion in these studies are highly suggestive of a need for accurate preoperative imaging of tumors. Nevertheless, the emphasis should be placed on the importance of LS for colorectal cancer being undertaken by appropriately trained surgeons.

The benefits of LS have been reported as decreased pain, early recovery, shorter hospital stay, and possibly better immunologic outcomes [1,3,4,5,7]. Despite these advantages in LS, the oncologic outcomes after laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery were not clearly superior to those following OS. Equivalent long-term oncologic outcomes for LS and OS have been reported in large scale randomized trials [2,6,9]; however, Lacy et al. [3,4] showed oncologic superiority of laparoscopic colectomy over open colectomy only for patients with stage III colon cancer. According to his study, laparoscopic colectomy was associated with significantly lower rates of tumor recurrence and a higher rate of overall survival. In his study, the oncologic outcomes for stages I and II colon cancers were similar for the two operations.

One possible explanation is that surgical stress impairs patients' immunity, and the probability of dissemination of advanced cancer during surgery may be increased [17,18]. LS is a less stressful procedure to the patients and provides the surgeon with minimal manipulation of the tumor compared to OS. Han et al. [19] suggested that laparoscopic colorectal surgery at clinical stage III had an immunological advantage of preserved mhuman leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR on postoperative day 5 even though oncologic benefit was not shown in those patients. Several reports have suggested a critical role for immunity in tumor progression and metastasis [20,21]. Further studies on the immunologic benefits are needed to draw a definitive conclusion regarding the benefits of LS.

Recent meta-analyses showed no oncologic benefits between LS and OS for the treatment of stages I-III colorectal cancer [22,23]. Martel et al. [22] reviewed randomized control trials of LS for colorectal cancer and showed no oncologic differences between LS and OS. In total, 5,782 patients were enrolled for the randomization of LS and OS for the patients of colorectal cancer. They found that LS was not inferior to OS in terms of overall survival (hazard ratio, 0.94; 95% confidence interval, 0.80-1.09) and that LS for rectal cancer remains controversial although it is becoming increasingly accepted since 2006. Trastulli et al. [23] analyzed nine randomized clinical trials for short and long-term outcomes between LS and OS in 1,544 rectal cancer patients. The use of LS for rectal cancer showed favorable short-term results in terms of low morbidity, earlier return of bowel function, and later oncologic outcomes compared to OS.

Disease free and overall survivals at five years for stage III colon cancer in long-term multicenter trials were similar for the laparoscopic and open surgeries [2,6]. No study has yet reported better oncologic outcomes for laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery compared to OS.

The results of long-term follow-up (median, 63 months) of CLASICC trial have been reported [10]. The long-term study reported no differences between LS and OS in terms of overall survival and disease-free survival. However, a trend towards improved overall survival was reported after OS compared to LS in stage III colon cancer (median overall survival: 79 months vs. 35 months; P = 0.031). Our prospective nonrandomized study aimed to evaluate the long-term oncologic outcomes of LS versus OS, especially for the curative management of stage III colorectal cancer. We obtained similar oncologic outcomes between both colorectal cancer groups, as most previous studies have also reported. Disease-free survival rate at five years (LG, 84.3%; OG, 90%; P = 0.507) for colon cancer and survival (LG, 83%; OG, 74.6%; P = 0.245) for rectal cancer were similar for the two groups. Likewise, overall five-year survival rate (LG, 72.2%; OG, 71.3%; P = 0.956) for colon cancer and the survival (LG, 68%; OG, 59%; P = 0.422) for rectal cancer were similar for the two groups. Therefore, our results do not support the idea that survival outcomes may be improved by the use of laparoscopic techniques due to any significant immunologic benefit from the laparoscopic approach for colon and rectal cancer.

In previous reports, the local recurrence following LS for stage I-III colon cancer and rectal cancer ranged from 2.3% to 10.8% [2,6,9] and 1% to 9.7% [8,11,15,24], respectively. Fleshman et al. [2] reported long-term follow-up in a COST (clinical outcomes of surgical therapy) study and showed a recurrence of over 30% for stage III colon cancer in the laparoscopic and open groups. Recently, Guerrieri et al. [25] reported better oncologic outcomes in terms of local recurrence and metastases in stage III colon cancer patients treated with LS compared to OS, although the incidence of peritoneal carcinosis did not differ between the two techniques. The possibility of local recurrences or metastases was 26.9% and 39.9% for LS and OS, respectively, with a median follow-up of 76.9 and 58 months. At 10 years, the local recurrence rate of right colonic cancer was higher than that of left colonic cancers (14.7 % vs. 5.2 %, P = 0.019). No differences in local recurrence were observed by randomized procedure [10]. In our study, overall recurrence rates for stage III colon and rectal cancer were similar for the two groups (P > 0.05). And right colon cancers showed similar local recurrence and overall survival rate compared with left colon cancer (P > 0.05). However, the recurrence rate for the rectal cancer OG was nearly two folds that of the LG, although the difference was not statistically significant (LG, 13.6%; OG, 23.6%; P = 0.191). We considered that the statistical similarity of recurrence rates may have resulted from the small sample size of the patients in each group.

In conclusion, our study may support the oncologic safety LS as a treatment for stage III colorectal cancer when compared to OS. Further prospective randomized studies are needed to draw a definitive conclusion.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Disease-free survival (DFS) of stage III colon cancer patients. LG, laparoscopic surgery group; OG, open surgery group.

Fig. 2

Disease-free survival (DFS) of stage III rectal cancer patients. LG, laparoscopic surgery group; OG, open surgery group.

Fig. 3

Overall survival (OS) of stage III colon cancer patients. LG, laparoscopic surgery group; OG, open surgery group.

Fig. 4

Overall survival (OS) of stage III rectal cancer patients. LG, laparoscopic surgery group; OG, open surgery group.

Table 1

Clinical characteristics of 230 patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%).

LG, laparoscopic surgery group; OG, open surgery group; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; RHC, right hemicolectomy; AR, anterior resection; HO, Hartmann's operation; LAR, low anterior resection; APR, abdominopelvic resection.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Gachon University research fund of 2013 (GCU-2013-M022).

References

1. Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group. A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350:2050–2059.

2. Fleshman J, Sargent DJ, Green E, Anvari M, Stryker SJ, Beart RW Jr, et al. Laparoscopic colectomy for cancer is not inferior to open surgery based on 5-year data from the COST Study Group trial. Ann Surg. 2007; 246:655–662.

3. Lacy AM, Garcia-Valdecasas JC, Delgado S, Castells A, Taura P, Pique JM, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted colectomy versus open colectomy for treatment of non-metastatic colon cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002; 359:2224–2229.

4. Lacy AM, Delgado S, Castells A, Prins HA, Arroyo V, Ibarzabal A, et al. The long-term results of a randomized clinical trial of laparoscopy-assisted versus open surgery for colon cancer. Ann Surg. 2008; 248:1–7.

5. Veldkamp R, Kuhry E, Hop WC, Jeekel J, Kazemier G, Bonjer HJ, et al. Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: short-term outcomes of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005; 6:477–484.

6. Colon Cancer Laparoscopic or Open Resection Study Group. Buunen M, Veldkamp R, Hop WC, Kuhry E, Jeekel J, et al. Survival after laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: long-term outcome of a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009; 10:44–52.

7. Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, Walker J, Jayne DG, Smith AM, et al. Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005; 365:1718–1726.

8. Jayne DG, Guillou PJ, Thorpe H, Quirke P, Copeland J, Smith AM, et al. Randomized trial of laparoscopic-assisted resection of colorectal carcinoma: 3-year results of the UK MRC CLASICC Trial Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25:3061–3068.

9. Jayne DG, Thorpe HC, Copeland J, Quirke P, Brown JM, Guillou PJ. Five-year followup of the Medical Research Council CLASICC trial of laparoscopically assisted versus open surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2010; 97:1638–1645.

10. Green BL, Marshall HC, Collinson F, Quirke P, Guillou P, Jayne DG, et al. Longterm follow-up of the Medical Research Council CLASICC trial of conventional versus laparoscopically assisted resection in colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2013; 100:75–82.

11. Leung KL, Kwok SP, Lam SC, Lee JF, Yiu RY, Ng SS, et al. Laparoscopic resection of rectosigmoid carcinoma: prospective randomised trial. Lancet. 2004; 363:1187–1192.

12. Braga M, Frasson M, Vignali A, Zuliani W, Capretti G, Di Carlo V. Laparoscopic resection in rectal cancer patients: outcome and cost-benefit analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007; 50:464–471.

13. Lee GJ, Lee JN, Oh JH, Baek JH. Mid-term results of laparoscopic surgery and open surgery for radical treatment of colorectal cancer. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2008; 24:373–379.

14. Laurent C, Leblanc F, Gineste C, Saric J, Rullier E. Laparoscopic approach in surgical treatment of rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2007; 94:1555–1561.

15. Ng KH, Ng DC, Cheung HY, Wong JC, Yau KK, Chung CC, et al. Laparoscopic resection for rectal cancers: lessons learned from 579 cases. Ann Surg. 2009; 249:82–86.

16. Staudacher C, Vignali A, Saverio DP, Elena O, Andrea T. Laparoscopic vs. open total mesorectal excision in unselected patients with rectal cancer: impact on early outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007; 50:1324–1331.

17. Decker D, Schondorf M, Bidlingmaier F, Hirner A, von Ruecker AA. Surgical stress induces a shift in the type-1/ type-2 T-helper cell balance, suggesting down-regulation of cell-mediated and up-regulation of antibody-mediated immunity commensurate to the trauma. Surgery. 1996; 119:316–325.

18. Vittimberga FJ Jr, Foley DP, Meyers WC, Callery MP. Laparoscopic surgery and the systemic immune response. Ann Surg. 1998; 227:326–334.

19. Han SA, Lee WY, Park CM, Yun SH, Chun HK. Comparison of immunologic outcomes of laparoscopic vs open approaches in clinical stage III colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010; 25:631–638.

20. Cole WH. The increase in immunosuppression and its role in the development of malignant lesions. J Surg Oncol. 1985; 30:139–144.

21. Da Costa ML, Redmond HP, Finnegan N, Flynn M, Bouchier-Hayes D. Laparotomy and laparoscopy differentially accelerate experimental flank tumour growth. Br J Surg. 1998; 85:1439–1442.

22. Martel G, Crawford A, Barkun JS, Boushey RP, Ramsay CR, Fergusson DA. Expert opinion on laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer parallels evidence from a cumulative meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e35292.

23. Trastulli S, Cirocchi R, Listorti C, Cavaliere D, Avenia N, Gulla N, et al. Laparoscopic vs open resection for rectal cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Colorectal Dis. 2012; 14:e277–e296.

24. Leroy J, Jamali F, Forbes L, Smith M, Rubino F, Mutter D, et al. Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision (TME) for rectal cancer surgery: long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2004; 18:281–289.

25. Guerrieri M, Campagnacci R, De Sanctis A, Lezoche G, Massucco P, Summa M, et al. Laparoscopic versus open colectomy for TNM stage III colon cancer: results of a prospective multicenter study in Italy. Surg Today. 2012; 42:1071–1077.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download