Abstract

Insulinomas are the most common pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Most insulinomas are benign, small, intrapancreatic solid tumors and only large tumors have a tendency for malignancy. Most patients present with symptoms of hypoglycemia that are relieved with the administration of glucose. We herein present the case of a 75-year-old woman who presented with an acute hypoglycemic episode. Subsequent laboratory and radiological studies established the diagnosis of a 17-cm malignant insulinoma, with local invasion to the left kidney, lymph node metastasis, and hepatic metastases. Patient symptoms, diagnostic and imaging work-up and surgical management of both the primary and the metastatic disease are reviewed.

Insulinomas, although rare, are the most common functioning islet tumors of the pancreas, with a reported incidence of 4 cases per 1 million patient-years [1]. Most insulinomas are benign (>90%), intrapancreatic solid tumors, less than 2-3 cm in diameter [1,2]. Larger tumors are more likely to be malignant [3]. In a small percentage (<10%), insulinomas can be associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type I syndrome, and then are usually multifocal [1,3]. Patients with insulinoma present with symptoms of fasting hypoglycemia that are relieved with the administration of glucose [4]. Inappropriately elevated levels of insulin (>3 µu/mL) and C-peptide (>0.2 nmol/L) combined with low blood glucose levels, below 50 mg/dL, are typical laboratory findings [5]. Preoperative localization, mainly with ultrasonography (US), multidetector CT or MRI, may be difficult for small tumors and thus intraoperative localization with ultrasound is recommended [2]. Surgical resection, either open or laparoscopic, is the treatment of choice, with high success rates [2,6]. We report a case of a giant malignant insulinoma that developed over a long period of time, measuring 17 cm × 15 cm and weighting 1,300 g, located in the body and tail of the pancreas. Local invasion into the left kidney, adrenal gland and the paraaortic lymph nodes was identified, with evidence of metastatic liver disease (pT4N1M1).

A 75-year-old woman was referred to our Emergency Department in a lethargic state, with acute onset of lightheadedness and diaphoresis. Serum glucose level was 30 mg/dL. The patient was given an intravenous bolus of 35% glucose solution and then continuous infusion of 10% dextrose. The patient reported similar but less severe episodes for the last 6 months that gradually increased in frequency.

Her past medical history was significant for heart failure, atrial fibrillation, hypothyroidism and osteoporosis and her medications included amiodarone, acenocoumarol, nitroglycerin, furosemide, spironolactone, levothyroxine and calcium carbonate. She had previously undergone cholocystectomy and total abdominal hysterectomy.

Our clinical examination was unremarkable. Her abdomen was soft and nontender. In deep palpation a fullness of the left upper quadrant of the abdomen was appreciated, but no definite masses were palpated.

To confirm the diagnosis of endogenous hyperinsulinemia from insulinoma, the patient underwent a supervised overnight fast during which she developed symptomatic hypoglycemia with serum glucose of 50 mg/dL. Insulin was 26 µIU/mL and C-peptide was 5.7 ng/mL. The contrast abdominal CT scan revealed a large heterogeneously enhancing lobulated mass located in the body and tail of the pancreas, with central necrosis and coarse calcifications. Similar large enhancing masses were also present at the left renal hilum and the left retrocrural space (Fig. 1). Multiple hypervascular metastases were also present in the liver. A preliminary diagnosis of malignant insulinoma was established (Figs. 2, 3).

Intraoperatively, a bulky tumor in the body and tail of the pancreas was identified that was firmly adherent to the omentum and the transverse colon. A second multilobular mass was firmly adherent to the left kidney and adrenal gland causing pressure signs and hydronephrosis. Metastatic lesions were identified at the left paraaortic area and the liver.

The patient underwent distal pancreatectomy, splenectomy, left nephrectomy and adrenalectomy and resection of the paraaortic masses, whereas the four hepatic lesions were treated with radiofrequency ablation.

Pathological exam revealed a 17 × 15 × 7-cm mass identified as a pancreatic insulinoma with malignant potential. Immunohistochemical staining revealed positivity for insulin, expression of CEA from tumor cells and 10 mitoses per 10 high-power fields. Vascular invasion, invasion of perinephric fat tissue and tumor necrosis were present. There was also invasion of the omentum and of the six lymph nodes in the spleen area (Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6).

During the first postoperative week, the patient was put on continuous intravenous infusion of 10% dextrose and subcutaneous administration of octreotide with serum glucose maintained above 65 mg/dL. The following week the patient remained euglycemic, with serum glucose levels ranging between 73-135 mg/dL, without glucose or octreotide administration and exited the hospital on the 12th postoperative day. At her routine follow-up visit 3 months postoperatively, she reported mild hypoglycemic symptoms and was put on diazoxide. The patient remains asymptomatic and disease-free after five years of follow-up.

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) are rare lesions. Functional PNETs secrete hormones causing evident clinical findings, whereas nonfunctional PNETs are not associated with specific hormonal response. The most common PNET is insulinoma. Most insulinomas are benign, intrapancreatic solid tumors, less than 3 cm in diameter. Less than 10% of insulinomas are associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type I syndrome. Larger tumors are more likely to be malignant [3].

Giant insulinomas reported in the literature range from 9 to 15 cm. Our case of a 17-cm malignant insulinoma is the largest insulinoma reported up to now.

Patients characteristically present with a triad of clinical findings first described by Whipple and Franz [4] in 1935: symptoms of hypoglycemia, low blood glucose levels less than 50 mg/dL and relief of the symptoms with the administration of glucose. Most patients present with symptoms of hypoglycemia, more notable after an overnight fast or strenuous exercise. Neuroglycopenic symptoms are the most common and include confusion, altered consciousness, anxiety, dizziness, lightheadedness, blurred vision, seizures, and coma. Sympathetic symptoms, such as palpitations, diaphoresis, sweating and tachycardia, may also be present. In our case we can only speculate that the insulinoma developed from a nonfunctional pancreatic tumor over a long period of time, thus the late onset of the symptoms.

The diagnostic work-up includes insulin and plasma proinsulin, C-peptide, and blood glucose levels measured after a 72-hour or, most commonly, after a 48-hour fasting. Imaging work-up includes preoperative US and localization with CT scan. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy was not performed due to its limited role in the evaluation of insulinomas since the somatostatin subtype-2 cell surface receptor is expressed in only 50% of the insulinomas [7].

Surgical resection of the primary tumor is the treatment of choice. In the presence of metastatic disease, surgical resection should include the metastatic lesions if possible. Although our patient presented with advanced disease, the preoperative evaluation showed that excision of the intra-abdominal masses and control of the metastatic disease was feasible. Laparoscopic resection is preferred for small-sized solitary tumors. Laparotomy is suited for larger tumors. We preferred an open approach for better exploration of the entire abdomen given the relation of the tumor to adjacent organs. The use of intraoperative US was of great assistance and the identified multifocal liver lesions were ablated by RF. Enucleation is preferred for small tumors in the body or tail of the pancreas, whereas distal pancreatectomy or Whipple procedure is mandatory for larger or malignant tumors [8].

Inhibitors of insulin secretion such as diazoxide, octreotide, phenytoin and verapamil have been used for the treatment of hypoglycemia but with temporary results. Streptozotocin, especially when combined with other chemotherapeutic agents like doxorubicin, has been shown to be effective in decreasing tumor size. Newer approaches include the use of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors like everolimus and rapamycin that show promising results [9].

Large insulinomas are rare PNETs with malignant potential. Surgical resection of the primary tumor and any metastatic lesions is the treatment of choice for these patients, offering long-term survival.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) Coronal volume rendering reformatted image demonstrates patent splenic artery surrounded by tumor (arrows). (B) Coronal maximum intensity projection reformatted image depicting patent portal and splenic vein (arrows).

Fig. 2

Post contrast axial CT image during arterial phase. Multiple hypervascular metastases are seen in liver.

Fig. 3

Post contrast reformatted CT images (A: coronal MPR, B: oblique MPR) during arterial phase. There is heterogeneously enhancing lobulated mass (arrows in A) in pancreatic tail with central necrosis (black block arrow in A). Coarse calcifications are also present within necrotic areas (white arrowhead in A). Large enhancing masses are also evident at level of left renal hilum (arrows in B) and at left retrocrural space (white arrow in A). Multiple hypervascular metastases are seen in liver (block arrowheads in B). MPR, multiplanar reformatting.

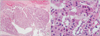

Fig. 4

(A, B) Microphotograph showing section from tumor with acinar pattern (H&E: A, ×100; B, ×400).

References

1. Service FJ, McMahon MM, O'Brien PC, Ballard DJ. Functioning insulinoma--incidence, recurrence, and long-term survival of patients: a 60-year study. Mayo Clin Proc. 1991; 66:711–719.

2. Kulke MH, Anthony LB, Bushnell DL, de Herder WW, Goldsmith SJ, Klimstra DS, et al. Tumor Society (NANETS). NANETS treatment guidelines: well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors of the stomach and pancreas. Pancreas. 2010; 39:735–752.

3. Mansour JC, Chen H. Pancreatic endocrine tumors. J Surg Res. 2004; 120:139–161.

4. Whipple AO, Frantz VK. Adenoma of islet cells with hyperinsulinism: a review. Ann Surg. 1935; 101:1299–1335.

5. Vinik AI, Woltering EA, Warner RR, Caplin M, O'Dorisio TM, Wiseman GA, et al. NANETS consensus guidelines for the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumor. Pancreas. 2010; 39:713–734.

6. Alexakis N, Neoptolemos JP. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008; 22:183–205.

7. Balon HR, Goldsmith SJ, Siegel BA, Silberstein EB, Krenning EP, Lang O, et al. Procedure guideline for somatostatin receptor scintigraphy with (111)In-pentetreotide. J Nucl Med. 2001; 42:1134–1138.

8. Tucker ON, Crotty PL, Conlon KC. The management of insulinoma. Br J Surg. 2006; 93:264–275.

9. Oberg K. Pancreatic endocrine tumors. Semin Oncol. 2010; 37:594–618.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download