Abstract

Purpose

Follow-up after primary treatment for breast cancer is an important component of survivor care and various international guidelines exist for the surveillance. However, little is known about current actual practice patterns of physicians whether they adhere to or deviate from recommended guidelines. The aim of this study was to determine how physicians follow-up their patients after primary treatment for breast cancer in Korea.

Methods

A questionnaire survey with 34 questions in 4 categories was e-mailed to the members of Korean Breast Cancer Society from November to December 2013. Respondents were asked how they use follow-up modalities after primary treatment of breast cancer and we compared the survey results with present guidelines.

Results

Of the 129 respondents, 123 (95.3%) were breast surgeons. The most important consideration in follow-up was tumor stage. History taking, physical examinations, and mammography were conducted in similar frequency recommended by other guidelines while breast ultrasonography was performed more often. The advanced imaging studies such as CT, MRI, and bone scan, which had been recommended to be conducted only if necessary, were also examined more frequently. Regular screenings for secondary malignancy were performed in 38 respondents (29.5%). Five years later after primary treatment, almost the whole respondents (94.6%) themselves monitored their patients.

According to the data from National Statistical Office published in 2013, the number of Korean cancer survivors (those who have received cancer treatment or are in treatment) is 1.1 million people, and breast cancer survivors among them are about 117,000 (10.7%), the 4th rank in the total cancer survivors [1]. As lifestyle is Westernized and concern for breast cancer increases, breast cancer patients sharply increase. And as the increase of survival rate of breast cancer due to the development of diagnosis and treatment techniques, the number of breast cancer survivors will be increased over years. Like this, in the situation where over 90% of Korean breast cancer patients survive more than 5 years after the primary treatment including a surgery, the optimal follow-up of breast cancer survivors is very important issue.

The purpose of follow-up of breast cancer patients can be summarized in 4 items: (1) recognition of recurrence or new primary cancer, (2) assessment for complications of therapy, (3) adherence to recommended therapy and screening, and (4) psychosocial and decision-making support [2,3]. Of these purposes, the early detection of new primary cancer or locoregional recurrence help improve the survival rate, but the diagnosis of distant metastasis is known to have no advantage in survival rate or health-related quality of life (QoL) [4,5]. Also, randomized controlled trials have found that reduced follow-up strategies did not negatively affect patient outcomes or early detection of recurrence, and more intensive follow-up was associated with higher costs without differences in early detection of relapses [6,7].

Since the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) published an evidence-based clinical practice guideline on breast cancer follow-up in 1997, various international guidelines have been published for the surveillance of breast cancer survivors [8]. These guidelines including Korean Breast Cancer Society (KBCS) guideline recommend the minimum follow-up including routine history, physical examination, and regularly scheduled mammography (MMG). In actual clinical situation, however, most breast cancer survivors want to receive more examinations because they are afraid of the recurrence when conducting follow-up after the primary treatment. Many physicians also tend to perform more tests more frequently than the extent recommended by the guidelines under the belief that they can increase the survival rate despite lack of evidence [9,10,11].

The follow-up guidelines for the breast cancer survivors published up to now are not stratified on the basis of stage or tumor biology, and there is no agreement on the optimal frequency or duration of follow-up modes. Moreover, little is known about current actual practice patterns of physicians and whether they adhere to or deviate from recommended guidelines. This study, therefore, attempted to investigate and analyze how, what tests, and on what interval KBCS members conduct during follow-up after primary treatment of breast cancer patients by using survey to prepare basic data that might be utilized to develop follow-up guideline indigenous to Korea.

The questionnaire of this study was developed by collaboration of the breast surgeon (H.J.Y.), a member of Korean Breast Cancer Survivor Research Group (KBCSRG) and the professor of preventive medicine (J.H.L.). Modification of the survey items was then performed by literature review and KBCSRG discussion. Before distribution, pilot test of the survey was performed in KBCSRG and the final construct was developed. The questionnaire consists of 34 questions in total 4 categories (basic information, considerable factor in follow-up, frequency of follow-up mode, and current practice of follow-up) (Supplementary material). It took an average of 7 minutes to complete the questionnaire and no incentive was provided to complete the survey. Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board.

The survey was conducted with 963 regular members of KBCS through total 3 e-mails from October 25, 2013 on 2-week interval. The survey was completed on November 30, 2013 and the results of the survey were collected by specialized software development company (Yeoulsoft, http://www.yeoulsoft.com).

Frequencies and percentages were used to display responses to individual questions. Descriptive analyses were performed by percentages. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for each follow-up modality in postoperative year. The result of the survey was compared and analyzed with well-known follow-up guidelines of breast cancer survivors.

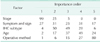

Of 963 members who received the questionnaires, a total of 129 members participated in the survey, showing the response rate of 13.4%. Those who were under 50 years old were 107 (82.9%) taking great part and the proportion of males to females was 2.4:1. One hundred twenty-three members (95.3%) of respondents were breast surgeons and there were 2 of each oncologist, radiologist, and radiation oncologist, respectively. Seventy-two respondents (55.8%), more than half, worked in Seoul and Gyeonggi regions and 67.4% of respondents (87 members) worked in university hospitals. Most respondents (117 members, 90.6%) were experienced physicians who have more than 2 years of experience of breast cancer treatment (Table 1).

The points that were considered important when performing follow-up after primary treatment of breast cancer were (1) stage, (2) symptoms and signs, (3) immunohistochemistry (IHC) type, (4) age, and (5) operative method in order (Table 2). Those who respond to apply different follow-up schedules for noninvasive breast cancer and invasive breast cancer patients were 89 members (69.0%) whereas those who answered that they performed follow-up equally according to stage in invasive breast cancer patients were 69 members (53.5%). The respondents who performed follow-up equally regardless of operative method (breast conserving surgery or mastectomy), IHC subtype, and BRCA mutation were 76.7%, 74.4%, and 64.3%, respectively. In the question that is there any change in the follow-up method and schedule after the implementation of 'Cancer Patient Registry' in which a patient receives medical expense curtailment benefit for 5 years after diagnosis of cancer effective from 2005, 41.6% (42/101) responded 'Yes.'

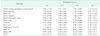

The frequency of each examination performed in follow-up was described by using mean ± SD according to postoperative years (Table 3). About 80% of respondents conducted history taking and physical examinations at least once every 6 months within 5 years after operation and once a year after 5 years. More than 50% of respondents conducted MMG, breast ultrasonography (US), laboratory test (including tumor markers), and chest x-ray once every 6 months within 5 years and once a year after that. The respondents conducted breast US 1.85 ± 0.6 times a years and MMG 1.53 ± 0.7 times year on average within postoperative 3 years, which showed that breast US was conducted more frequently than MMG. About 50% of respondents said they performed chest CT more than once a year within 5 years and those who conducted it regularly after postoperative 5 years were 17%. Also, the respondents who conducted more advanced imaging studies such as abdominal US, CT, and bone scan more than once a year within postoperative 5 years were more than 70% and about 40% of respondents said they conducted those tests more than once a year after 5 years. Most respondents (95.3%) examined brain CT only if necessary such as in case when patients complain of symptoms and 15% of respondents conducted breast MRI at least once a year within postoperative 5 years. Fifty percent of respondents conducted PET-CT more than once a year within 3 years, and 50% of respondents conducted it once every 2 years after 4-5 years. Fifteen percent of respondents conducted the test regularly even after 5 years. Seventy three respondents (56.6%) were found to conduct PET-CT and general tests (US, CT, bone scan, etc.) alternately to check whether the cancer metastasized to other organs.

Tumor markers that were regularly measured were CA 15-3 (93.8%) and CEA (73.6%), but CA 27.29 (3.1%) was not mostly measured. Eighty seven respondents (67.4%) measured bone mineral density (BMD) regularly and 45.7% (59 members) said they conducted gynecological examination regardless of tamoxifen intake.

Thirty-eight respondents (29.5%) conducted the tests to detect the secondary malignancy that occur in other organs in addition to breast (endoscopy, neck US, etc.) and the objects to be tested were thyroid, stomach, large intestine, ovary, etc.

Most respondents (122, 94.6%) have themselves conducted continuous follow-up after 5 years for patients who do not show particular features such as recurrence and metastasis after primary treatment and only 5 respondents (3.9%) delivered the case to the region where patients reside, other than the hospital in which the respondent worked.

For the methods to contact the medical team when breast cancer survivors showed a new symptom or had any questions were mainly direct visits (44.2%) and phone calls to outpatient clinic (33.3%) (Fig. 1). The guidelines that were referred to when conducting follow-up were KBCS (48.0%) and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline (45.0%), taking about half and half.

Because follow-up after primary treatment of breast cancer patients improves survival rate and is important as an instrument to increase QoL, the follow-up guidelines are suggested by many professional societies including KBCS to increase the efficiency of medical treatment. According to these guidelines, contralateral breast cancer, ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence, and chest wall recurrence have great possibility to be fully recovered when they are detected early. However, since the early detection of distant metastasis which occurs in other organs such as bone, lung, and liver does not help improve the survival rate, most guidelines recommend simplified follow-up protocols. In other words, the existing follow-up guidelines including KBCS guideline recommend regular history taking, physical examinations, and MMG, and other laboratory and imaging tests are not recommended for routine follow-up in an otherwise asymptomatic patient with no specific findings on clinical examination. Gynecological examinations are recommended for women receiving tamoxifen, and regular BMD is recommended for women receiving aromatase inhibitors [12]. The systemic reviews on breast cancer follow-up recently reported also showed that there is no survival benefit in diagnosing recurrence prior to the occurrence of symptoms, supporting the validity of simple follow-up protocols [13,14].

There is a report that the intensity of follow-up testing does not affect the emotional well-being or QoL of breast cancer survivors. Rather, when they visit on the expected outpatient visit day, especially after tests, they were very stressful, and more than 70% of patients feel anxiety [15]. Follow-up tests themselves also may cause psychosocial and physical harm in healthy survivors owing to false-positive findings, unnecessary investigations, and overtreatment [16]. Despite these reports, both patients and physicians in actual clinical situations do not perform present follow-up guidelines and conduct a variety of surveillances under the belief that intensified follow-up will increase diagnostic security and survival [10,11]. In other words, despite the evidence of well-designed randomized controlled trial, there are still a lot of debates on optimal follow-up modality, frequency, and duration for breast cancer survivors. For example, physicians traditionally think that breast cancer recurs within 5 years after primary treatment. Most guidelines drastically reduce follow-up after 5 years, but, as it turned out, because hormone receptor positive breast cancer shows slow relapse more than 10 years, the physicians suggest that follow-up strategies based on not tumor stage but biology should be considered. In this survey, many respondents said that the factor they considered most during follow-up of breast cancer survivors was stage, but only 46.5% of respondents conducted different follow-up depending on stage in invasive breast cancer patients. The follow-up considering biological factors including IHC subtype or BRCA mutation were only 25.6% and 35.7%. It is thought that the study related to this area must be conducted in the future.

The important finding in this study is that although the respondents are mostly experienced physicians, they conducted intensive follow-up more frequently than the recommendation of the existing follow-up guidelines. Despite the systemic review that routine history taking and physical examinations do not likely detect treatable relapse and they cannot increase survival outcome [17], they are the modalities that were most frequently performed in follow-up. This survey also shows 2.88 times in postoperative year 1 and 1.12 times per year after 5, which are the result similar to the existing guidelines including KBCS. Annually mammographic surveillance was very effective imaging modality which detects about 50% of breast recurrences [17], and this method is recommended in all guidelines as it was known as the only way to increase the survival rate of breast cancer patients [18,19]. As a result of this survey, it was conducted 1.3 times in postoperative year 4-5, which is more frequently conducted than overseas guidelines. The most striking finding is breast US, which is recommended to be conducted annually in KBCS and only if necessary in overseas guidelines, was in fact conducted more frequently than MMG. Such result was inferred to be caused by the low cost and accessibility of US in Korea. Also, Korea has 'Cancer Patient Registry,' a special law, and survivors can receive diagnosis and treatment without great economic burden. This is why the guideline in Korea is different from the overseas guidelines. This was confirmed in the result of the survey that 41.6% of respondents answered that their follow-up modalities were changed after the implementation of 'Cancer Patient Registry.'

Chest x-ray was conducted 1.5 times/yr within postoperative 5 years, which was more frequent than the existing guidelines that recommend that it should be conducted only if necessary. The laboratory tests were to be conducted only if necessary in the guidelines because there was no evidence to improve survival or QoL, but in fact they conducted the tests twice a year up to 5 years after primary treatment. This was consistent with the report of Margenthaler et al. [11]. The respondents comply with KBCS guideline that tumor markers should be conducted once every 6 months within 5 years after primary treatment and then annually afterwards, and CA 27.29 was not rarely measured, not like overseas guideline. Recently, "Top Five" list, the guideline for advanced imaging tests such as tumor markers, CT, PET, bone scan, etc., which have been clinically conducted during follow-up of breast cancer survivors without strong clinical evidence has been suggested by ASCO [20]. This guideline recommends that the above tests should not be conducted because they do not improve outcome, only inducing risk of unnecessary morbidity, high cost, and patient's anxiety. This study showed that nonrecommended testing has decreased over time. However, over 70% of respondents said they conducted the above tests more than once a year within postoperative 5 years, showing a big difference from the guideline.

The follow-up visits of breast cancer survivors should include not only detection of breast cancer recurrence, but also general health maintenance, patient education, and psychosocial support [21,22]. Physicians should suggest adequate lifestyle including diet and exercise, give education about symptoms suspected for recurrence and complications such as lymphedema and osteoporosis which can occur after treatment, and provide supportive care on depression, anxiety, or distress, which can occur during diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. 67.4% of respondents regularly conducted BMD and 45.7% regularly conducted gynecological examination in this survey. Although the physicians in Korea have a lot of concerns for general health maintenance, the above purpose of follow-up is hard to achieve because of concentration of medical treatment and low charge for medical treatment, which are the reality that must be improved.

Because breast cancer survivors have greater risk of the secondary malignancy than general population because of genetic mutation, environmental exposure, or a consequence of specific therapy, the tests related to the secondary malignancy should be included in follow-up [23]. ASCO guideline also recommends screening of secondary malignancy including cervical and colorectal cancer. Since only 29.5% of respondents conducted the screening regularly, it's considered that more recommendations are needed in this area.

Because of difference of individual opinions on the usefulness of follow-up, several larger studies report of poor adherence on guidelines [24,25]. As only 50%-80% of respondents even conducted MMG, which proved its survival benefit, annually according to the guideline, they observed both overuse and underuse of follow-up tests and visits. In this survey, most of respondents (93.0%) said that they conducted follow-up in consideration of KBCS and NCCN guidelines, but in fact, they conducted more tests more frequently than the recommendation of the existing guidelines. The follow-up programs indigenous to physicians based on their abundant clinical experiences are important, but it is very important to develop systemic follow-up strategy for Korean according to recurrence risk and specific personality of breast cancer survivors in the future.

It is unclear which type of providers is most suitable to follow-up for breast cancer survivors. According to ASCO guideline, because the risk of recurrence of breast cancer continues even after 15 years after primary treatment, the guideline recommends that the coordination of care of oncologist and primary care physician (PCP) is very important for adequate follow-up of breast cancer survivors. The follow-up by PCP shows the health outcomes equivalent to the follow-up by oncologist with good patient satisfaction [26].

However, for KBCS respondents, 94.6% of oncologists conducted follow-up even after 5 years, indicating that effective delivery system is not operated at all. The future viability of oncologist-only survivorship care is uncertain. Although Korean breast cancer survivors have tendency to prefer oncologists compared to overseas, it is needed to provide the system in which breast cancer survivors can receive better follow-up through adequate delivery system education which reflects the medical characteristics in Korea for both oncologists and PCPs, and through smooth communication between them. On the other hand, the 'Institute of Medicine' recommends that all cancer survivors should receive survivorship care plans including clear and effective future treatment plans which reflect timing and content of follow-up [27]. Thus, we need to develop Korean survivorship care plans which include the summary of treatment of individual patients and the future treatment plan for sound follow-ups of breast cancer survivors. The development of this plan is the essential element to accomplish the adequate delivery system.

When breast cancer survivors have new symptoms or questions to ask, the main contact methods were that they should visit (44.2%) or make phone calls (33.3%) to outpatient clinic. There is some evidence that modern technologies can be used to safely and effectively deliver aspects of survivor follow-up as an alternative to existing traditional models [28]. According to a recent randomized trial, Facebook-based intervention may help cancer survivors receive health information and support to promote physical activity and other health behaviors [29]. Since such electrical health (including mobile health) can improve disease outcomes as well as related QoL among breast cancer survivors, more studies on it as one of modality of the future follow-up should be conducted.

The present study has several limitations. First, the response rate of the survey was only 13.4%, which shows the possibility that it could not reflect the whole opinion of KBCS membership. Second, because the questionnaires were e-mailed to only KBCS members, the practices of other physicians including medical oncologists who actually follow-up many breast cancer survivors were not reflected. Third, respondents might have 'recall bias' while they thought about follow-up modalities that they actually performed. Despite these limitations, this study can have its significance to provide valuable information on what tests experienced KBCS members would conduct, on what interval they do, and what they consider when doing follow-up for survivors after primary treatment of breast cancer. In addition, this study provides an opportunity to use basic data to develop follow-up guideline indigenous to Korean breast cancer survivors. Further well-designed prospective studies are needed to determine the comparative effectiveness of different modes of breast cancer surveillance and the ideal frequency and duration of follow-up.

In conclusion, it was found that a majority of respondents have performed intensive follow-up modalities in comparison with present guidelines and screenings for secondary malignancy less frequently in the survey with KBCS members on follow-up modality that is conducted after primary treatment of breast cancer patients. Also, it was found that it is necessary to suggest some measures for adequate delivery system for breast cancer survivors, which is not established in the current clinical environment. It is considered that the follow-up guideline indigenous to Korean breast cancer survivors through prospective clinical trials on clinical efficacy of each follow-up strategy in the future.

Figures and Tables

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are most grateful to the members of the KBCS who provided critical feedback on the questionnaire. This work was supported by the Korea Breast Cancer Foundation.

References

1. Statistics Korea, Korean Statistical Information Service. 2013 Cancer registry statistics in Korea [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea, Korean Statistical Information Service;1996. cited 2014 Jul 15. Available from: http://kosis.kr.

2. Burstein HJ, Winer EP. Primary care for survivors of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000; 343:1086–1094.

3. Emens LA, Davidson NE. The follow-up of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2003; 30:338–348.

4. Dalberg K, Mattsson A, Sandelin K, Rutqvist LE. Outcome of treatment for ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence in early-stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998; 49:69–78.

5. Palli D, Russo A, Saieva C, Ciatto S, Rosselli Del Turco M, Distante V, et al. Intensive vs clinical follow-up after treatment of primary breast cancer: 10-year update of a randomized trial. National Research Council Project on Breast Cancer Follow-up. JAMA. 1999; 281:1586.

6. Oltra A, Santaballa A, Munarriz B, Pastor M, Montalar J. Cost-benefit analysis of a follow-up program in patients with breast cancer: a randomized prospective study. Breast J. 2007; 13:571–574.

7. Sheppard C, Higgins B, Wise M, Yiangou C, Dubois D, Kilburn S. Breast cancer follow up: a randomised controlled trial comparing point of need access versus routine 6-monthly clinical review. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2009; 13:2–8.

8. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Recommended breast cancer surveillance guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 1997; 15:2149–2156.

9. Elston Lafata J, Simpkins J, Schultz L, Chase GA, Johnson CC, Yood MU, et al. Routine surveillance care after cancer treatment with curative intent. Med Care. 2005; 43:592–599.

10. Hans-Joachim S, Dorit L, Petra S, Ingo B, Steffen K, Alexander FP, et al. The reality in the surveillance of breast cancer survivors-results of a patient survey. Breast Cancer (Auckl). 2008; 1:17–23.

11. Margenthaler JA, Allam E, Chen L, Virgo KS, Kulkarni UM, Patel AP, et al. Surveillance of patients with breast cancer after curative-intent primary treatment: current practice patterns. J Oncol Pract. 2012; 8:79–83.

12. Noh WC. Korean Breast Cancer Society guideline. Korean Breast Cancer Society. The breast. 3rd ed. Seoul: Goonja;2013. p. 824.

13. Rojas MP, Telaro E, Russo A, Moschetti I, Coe L, Fossati R, et al. Follow-up strategies for women treated for early breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005; (1):CD001768.

14. Khatcheressian JL, Hurley P, Bantug E, Esserman LJ, Grunfeld E, Halberg F, et al. Breast cancer follow-up and management after primary treatment: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31:961–965.

15. Paradiso A, Nitti P, Frezza P, Scorpiglione N. A survey in Puglia: the attitudes and opinions of specialists, general physicians and patients on follow-up practice. G.S.Bio. Ca.M. Ann Oncol. 1995; 6:Suppl 2. 53–56.

16. Brodersen J, Jorgensen KJ, Gotzsche PC. The benefits and harms of screening for cancer with a focus on breast screening. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2010; 120:89–94.

17. Montgomery DA, Krupa K, Cooke TG. Follow-up in breast cancer: does routine clinical examination improve outcome? A systematic review of the literature. Br J Cancer. 2007; 97:1632–1641.

18. Paszat L, Sutradhar R, Grunfeld E, Gainford C, Benk V, Bondy S, et al. Outcomes of surveillance mammography after treatment of primary breast cancer: a population-based case series. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009; 114:169–178.

19. Lash TL, Fox MP, Buist DS, Wei F, Field TS, Frost FJ, et al. Mammography surveillance and mortality in older breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25:3001–3006.

20. Schnipper LE, Smith TJ, Raghavan D, Blayney DW, Ganz PA, Mulvey TM, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology identifies five key opportunities to improve care and reduce costs: the top five list for oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2012; 30:1715–1724.

21. Kimman ML, Voogd AC, Dirksen CD, Falger P, Hupperets P, Keymeulen K, et al. Follow-up after curative treatment for breast cancer: why do we still adhere to frequent outpatient clinic visits? Eur J Cancer. 2007; 43:647–653.

22. Renton JP, Twelves CJ, Yuille FA. Follow-up in women with breast cancer: the patients' perspective. Breast. 2002; 11:257–261.

23. Curtis RE, Ron E, Hankey BF, Hoover RN. New malignancies following breast cancer. In : Curtis RE, Freedman DM, Ron E, Ries LA, Hacker DG, Edwards BK, editors. New malignancies among cancer survivors: SEER Cancer Registries, 1973-2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, NIH Publishing;2006. p. 181–205.

24. Grunfeld E, Hodgson DC, Del Giudice ME, Moineddin R. Population-based longitudinal study of follow-up care for breast cancer survivors. J Oncol Pract. 2010; 6:174–181.

25. Keating NL, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Winer EP, Ayanian JZ. Surveillance testing among survivors of early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25:1074–1081.

26. Grunfeld E, Levine MN, Julian JA, Coyle D, Szechtman B, Mirsky D, et al. Randomized trial of long-term follow-up for early-stage breast cancer: a comparison of family physician versus specialist care. J Clin Oncol. 2006; 24:848–855.

27. Institute of Medicine. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Washington, DC: National Academy Press;2006. p. 151–156.

28. Dickinson R, Hall S, Sinclair JE, Bond C, Murchie P. Using technology to deliver cancer follow-up: a systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2014; 14:311.

29. Valle CG, Tate DF, Mayer DK, Allicock M, Cai J. A randomized trial of a Facebookbased physical activity intervention for young adult cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2013; 7:355–368.

Supplementary Material

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material can be found via http://www.thesurgery.or.kr/src/sm/astr-88-133-s001.pdf.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download