Abstract

Malaria can present with various clinical symptoms and complications. While a tertian malaria form that is especially prevalent in Korea is characterized by mild clinical progression, occasional splenic complications are known to occur. A 26-year-old Korean male soldier without prior medical history visited The Armed Forces Capital Hospital with left upper quadrant abdominal pain one day ago. Hemostasis under laparoscopic approach was attempted. The operation was converted into laparotomy due to friable splenic tissue and consequently poor hemostasis. Splenectomy was performed. The patient was discharged at postoperative day 17 without complication. While numerous diseases can result in splenic complications, such as splenic rupture, malarial infection is known as the most common cause. The incidence of malarial infection in Korea is increasing annually, and there are occasional reports of splenic rupture due to the infection, which requires attention.

Malaria is a parasitic disease caused by infection with Plasmodium species of phylum protozoa and subphylum haplosporea that resides in red blood cells. Korea has a long history of malaria-it was recorded in Dongeuibogam, an important text on Korean traditional medicine, and it was especially prevalent nationwide during the Korean War [1,2]. Humans and mosquitoes are intermediate and final host of malaria, respectively. Four species of malaria-Plasmodium falcifarum, Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium malariae, and Plasmodium ovale-are known to infect humans, and only P. vivax has been reported as a cause of endemic malaria in Korea [2].

Malaria can present with various clinical symptoms and complications. While the tertian malaria form that is especially prevalent in Korea is characterized by mild clinical progression, occasional splenic complications are known to occur [3], which requires attention. Here, we report our experience with a case of spontaneous splenic rupture that occurred in patients infected with endemic malaria, along with appropriate literature review.

A 26-year-old Korean male soldier without prior medical history visited The Armed Forces Capital Hospital with left upper quadrant abdominal pain one day ago. He has been assigned to duty around the northern boundary line of South Korea where malaria is an endemic disease. The patient reported periodic fever that started 1 week prior and underwent evaluation in another hospital 3 days ago where the diagnosis of tertian malaria was confirmed. The patient was hospitalized and received hydroxychloroquine while under close observation, but further symptoms presented during the course of the disease, and he was transferred to our hospital. Physical examination showed left upper quadrant tenderness and rebound tenderness. Conjunctival pallor and abdominal distension were noted. The spleen was palpable 5 to 6 cm below the left costal margin. Blood pressure was 132/63 mmHg, pulse, 112/min, and body temperature, 36.6℃. Laboratory test revealed anemia (hemoglobin, 9.5 g/dL), thrombocytopenia (30 k/uL), AST, 20 IU/L, ALT, 25 IU/L, BUN, 12.6 mg/dL, and creatinine, 0.8 mg/dL. Rapid blood assay tested positive for P. vivax antigen. The diagnosis was confirmed by peripheral blood smear with P. vivax. Prompt investigation with multi-detector CT allowed confident diagnosis of diffuse, moderately hemoperitoneum and splenomegaly with perisplenic hematoma (Fig. 1).

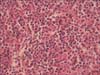

Bleeding control under laparoscopic approach was attempted. Intraoperative findings revealed approximately 1,000 mL of blood collection in the peritoneum, in addition to splenomegaly and capsule rupture (Fig. 2). The operation was converted into laparotomy due to friable splenic tissue and consequently poor hemostasis. Splenectomy was performed. Microscopic evaluation of the spleen did not find subcapsular hematoma or infarct, but did note malarial pigment within the histiocytes located in the red pulp cord (Fig. 3).

The patient underwent intensive treatment for 4 days in the intensive care unit and was administered primaquine phosphate (15 mg base/day) for 2 weeks starting from the day of operation. The patient was discharged at postoperative day 17 without complication.

Most of the cases of spontaneous splenic rupture in malaria occur during acute infection and are associated with P. vivax, although there have been rare cases associated with other Plasmodium species [4]. Review articles have reported only 22 malaria cases with spontaneous splenic rupture in the English language literature since 1960. The predominant Plasmodium species in these cases were P. vivax (15 patients), followed by P. falciparum (5 patients) and P. malariae (2 patients) [5].

The spleen plays an important role in malaria, producing antibodies against the malarial parasite. The splenic complications of Plasmodium infection are hematoma, rupture, hypersplenism, ectopic spleen, torsion, cyst, and infarction. Splenomegaly occurs earlier compared to other complications, such as rupture [3,6]. A palpable spleen may be present within 3 to 4 days of the onset of symptoms and may be noted in 50% to 90% of patients with malaria [4,7]. The spleen may subsequently become more hyperemic, swollen and tender with each febrile paroxysm, though partial resolution can occur between paroxysm, though partial resolution can occur between paroxysm. Following appropriate treatment, the spleen usually decreases in size within days to weeks [4,6].

The mechanism of spleen rupture remains poorly defined. Three mechanisms have been suggested so far. The first of these mechanisms is an increase in intrasplenic tension due to cellular hyperplasia and engorgement. Second, the spleen may be compressed by abdominal musculature during physiological activities such as sneezing, coughing, defecating, and sitting up or turning in bed. Third, vascular occlusion due to reticuloendothelial hyperplasia may be involved, which ultimately results in thrombosis and infarction. This leads to interstitial and subcapsular hemorrhage and stripping of the capsule, which further results in the distended capsule finally giving way [5,7].

The treatment of choice of spontaneous splenic rupture accompanied with malaria has traditionally been splenectomy [8]; however, due to recent advances in surgical techniques and conservative treatment, as well as studies in postoperative risks of splenectomy, it is now more common to apply conservative treatment in the setting of stable vital signs and lack of progression of hemorrhage [4,8,9]. In specific malaria-endemic regions, malaria occurring after splenectomy can be fatal, which requires continued prophylactic treatment, and there are possibilities of latent malaria following the operation, which does warrant surgical treatment [9]. However, spleen-conserving operation as presented in this case may be attempted, and there have been reports of successful outcomes through this approach [10]. Therefore, a laparoscopic approach as reported in this case may be a possible method, and a conservative treatment may be more appropriate if the patient's condition is stable.

While numerous diseases can result in splenic complications, such as splenic rupture, malarial infection is known as the most common cause. The incidence of malarial infection in Korea is increasing annually, and there are occasional reports of splenic rupture due to the infection, which requires attention. We have reported our experience with splenic rupture due to malarial infection treated with surgical approach in a military hospital, in addition to literature review.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Abdominal compute tomography finding reveal splenomegaly, perisplenic fluid collection, and hematoma.

References

1. Chun CH, Kim JJ. Malaria in Korea. Korean Med. 1959; 2:63–66.

2. Song HO, Park MK, Hyun CL. Analysis of multidrug resistant gene mutation in Plasmodium vivax. J Korean Mil Med Assoc. 2012; 43:1–13.

3. Clezy JK, Richens JE. Non-operative management of a spontaneously ruptured malarial spleen. Br J Surg. 1985; 72:990.

4. Ozsoy MF, Oncul O, Pekkafali Z, Pahsa A, Yenen OS. Splenic complications in malaria: report of two cases from Turkey. J Med Microbiol. 2004; 53(Pt 12):1255–1258.

5. Patel MI. Spontaneous rupture of a malarial spleen. Med J Aust. 1993; 159(11-12):836–837.

6. Zingman BS, Viner BL. Splenic complications in malaria: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1993; 16:223–232.

7. Tauro LF, Maroli R, D'Souza CR, Hegde BR, Shetty SR, Shenoy D. Spontaneous rupture of the malarial spleen. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2007; 13:163–167.

8. Schuler JG, Filtzer H. Spontaneous splenic rupture. The role of nonoperative management. Arch Surg. 1995; 130:662–665.

9. Hamel CT, Blum J, Harder F, Kocher T. Nonoperative treatment of splenic rupture in malaria tropica: review of literature and case report. Acta Trop. 2002; 82:1–5.

10. Opondo E, Khan MR. Laparoscopic conservative management of a spontaneously ruptured spleen: case report. East Afr Med J. 2008; 85:616–618.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download