Abstract

Purpose

Multiple segment 5 vein (V5) anastomoses are common and inevitable in living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) using modified right lobe (MRL) graft. Sacrifice of segment 4a vein (V4a) can simplify bench work and avoid graft congestion. But it could be harmful to some donors in previous simulation studies. This study aimed to evaluate donor safety in LDLT using caudal middle hepatic vein trunk preserved right lobe (CMPRL) graft.

Methods

LDLT using MRL grafts were performed on 33 patients (group A) and LDLT using CMPRL grafts were performed on 37 patients (group B). Group B was classified into 2 subgroups by venous drainage pattern of segment 4: V4a dominant drainage group (group B1) and the other group (group B2). Parameters compared between group A donors and group B donors included operation time, bench work time, number and diameter of V5, remnant liver volume and postoperative course. Those were also investigated in group B1 compared with group B2. And, we reviewed postoperative course of the recipients in groups A and B.

As cadaveric organ shortage becomes a critical problem, living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) is now widely performed to expand the donor pool, especially in East Asia [1]. LDLT using right lobe (RL) graft is now a standard procedure for adult patients in order to alleviate the problem of graft size insufficiency. RL graft without middle hepatic vein (MHV) is commonly used to secure donor safety in LDLT using RL graft. In this situation, congestion of the right anterior sector can occur and lead to graft failure [2,3,4,5]. Lee et al. [6] first suggested the modified right lobe (MRL) graft with reconstruction of MHV tributaries to resolve this problem in 2002 and this procedure has been accepted widely.

Multiple MHV tributaries draining segment 5 vein (V5) are found commonly in donor hepatectomy using conventional MRL graft, and multiple anastomoses are inevitable. Graft congestion caused by small-calibered MHV tributaries can cause adverse effects on regeneration of the graft and recovery of the recipient. To overcome these problems, recently we have tried to use RL graft with sacrifice of MHV tributaries draining the inferior part of segment 4a vein (V4a). From this procedure we can get one large-calibered orifice of V5. We named this graft as "caudal middle hepatic vein trunk preserved right lobe (CMPRL) graft". Partial or total sacrifice of V4a can simplify bench work and avoid graft congestion. But according to previous simulation studies, it could be harmful to donors in terms of remnant liver congestion [7].

This study aimed to evaluate donor safety in LDLT using CMPRL graft.

During the period from May 2010 to September 2013, 70 LDLTs were performed with RL grafts in Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital. LDLT using conventional MRL grafts were performed on 33 patients (group A) and LDLT using CMPRL grafts were carried out on 37 patients since December 2011 (group B). Group B was classified into 2 subgroups by predominant venous drainage pattern of segment 4a vein (S4) based on CT: V4a dominant drainage group (group B1) and the other-superior part of S4 hepatic vein (V4b) dominant drainage or left hepatic vein (LHV) dominant drainage-group (group B2).

The same protocol was used for all donor selection. Potential donors were evaluated through laboratory and serologic analyses to exclude any abnormalities suggesting liver disease. Detailed imaging studies including CT and MRI were performed to evaluate the vascular anatomy, biliary structure and liver volume. Liver biopsies were undertaken in all donors. Absolute exclusion criteria were any underlying medical condition that was considered to increase complications, ABO incompatibility, positive hepatitis serology, underlying liver disease, future remnant liver volume <30% and fatty change >30%.

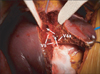

All donor hepatectomies were performed without blood transfusion. During donor hepatectomy with CMPRL graft, the initial parenchymal transection plane was the same with conventional right hepatectomy. When encountering the MHV or V5 peripherally, the transection line was modified to the left side of the MHV. After full exposure of the left side of caudal MHV trunk, the right side of cranial MHV trunk was fully exposed until the junction of the MHV and inferior vena cava. Then, exposed V4a was sacrificed partially or totally. As a result, a single large orifice of V5 was obtained with caudal MHV trunk (Fig. 1). In bench work, anastomosis was very simple and standardized; a single large orifice of V5 was anastomosed with a ringed Gore-Tex graft in end-to-end fashion and segment 8 vein (V8) was anastomosed in end-to-side fashion (Fig. 2).

The clinical data from the donors and recipients were analyzed retrospectively. Parameters compared between group A donors and group B donors included operation time, bench work time, number and diameter of V5, remnant liver volume, length of hospital stay, length of intensive care unit (ICU) stay, major complications, and laboratory findings on postoperative days (POD) 1, 3, and 5. Those were also investigated in group B1 compared with group B2 to evaluate the impact of the absence of dominant drainage vein of S4. And, we reviewed postoperative course of the recipients in groups A and B, which included liver function test, volume of the ascites on POD 7, MHV stent insertion rate and patency rate of V5 at one month and 3 months after LDLT. The chi-square test was used for comparisons of discrete variables and Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison of continuous variables. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 21.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

Operation time and bench work time in group B were 377.70 ± 51.08 minutes, 48.22 ± 8.49 minutes, respectively, and significantly shorter than those in group A (operation time, P = 0.000; bench work time, P < 0.001). V5 number was 1.36 ± 0.60 (range, 1-3) in group A, 1 in group B, and there was significant difference (P = 0.002). V5 diameter was significantly larger in group B (P < 0.001). The preoperative expected remnant liver volume expressed as a ratio of the CT volume of the left lobe volume to that of the whole liver showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups (35.77 ± 3.94 in group A vs. 36.82 ± 3.71 in group B, P = 0.252).

Postoperative donor recovery between the two groups was comparable. Fig. 3 shows serial changes of surrogate markers of remnant liver function after operation. AST, ALT, and serum bilirubin were checked on POD 1, 3, and 5; there were no significant differences between the two groups. On the other hand, PT checked on POD 1 and 5 was higher in group B and there was significant difference (POD 1, P = 0.010; POD 5, P = 0.008). However, PT on POD 5 in both groups A and B decreased to near normal range (group A, 12.79 ± 0.86; group B, 13.40 ± 1.00), so this result does not directly mean an adverse outcome of CMPRL graft. Actually, patients with PT value in these ranges do not need medical intervention such as fresh frozen plasma infusion. Durations of hospital stay and ICU stay were not significantly different between the two groups. Major complications needing surgical or nonsurgical intervention occurred to 2 donors in group A (1 bile leak and 1 portal vein stenosis) and 3 donors in group B (2 bleedings and 1 portal vein stenosis), but this result was comparable between the two groups (P = 0.658) (Table 1). All donors are alive and back to their predonation lifestyles.

Of group B, 22 cases were classified to group B1 and 15 cases were classified to group B2. Operation time and bench work time showed no significant differences between the two groups. V5 diameter was comparable between the two groups (operation time, P = 0.232; bench work time, P = 0.366). Remnant liver volume was similar in the two groups (36.32 ± 3.79 in group B1 vs. 37.56 ± 3.59 in group B2, P = 0.325). In data related to postoperative course such as length of hospital stay and ICU stay, major complications were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 2). Fig. 4 shows laboratory results in the two groups. Remnant liver function on POD 1, 3, and 5 showed no significant differences except PT on POD 3 (P = 0.016). We also investigated congestion area of S4 in each group by CT. Among group B2, congestion of S4 in abdominal CT follow-up after donor hepatectomy occurred to one donor. In group B1, congestion of S4 occurred to 5 donors, but territory of the congestion was relatively small and did not affect patients' outcome, and there was no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.368).

Recipients of groups A and B had similar distributions of age, sex, Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score and graft-to-recipient body weight ratio (GRWR). With regard to liver function tests, there was no significant difference in peak AST, ALT, PT, and serum bilirubin levels between the two groups. Volume of ascites on POD 7 also showed similar value between the two groups.

In terms of V5 patency rate, recipients with CMPRL graft showed better results. One-month patency rate of V5 was 75.8% in group A and 94.6% in group B, and there was significant difference (P = 0.038). Three-month patency rate of V5 was 48.5% in group A and 82.8% in group B, and these result also showed significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.001). Stent insertion was needed in 5 recipients of group A and one recipient of group B, but there was no significant difference (P = 0.093) (Table 3).

After LDLT using conventional RL graft, graft congestion of right anterior section can occur and sometimes it may lead to serious complications including graft loss [3,8,9]. Some operative techniques were developed to avoid this problem. LDLT using extended RL graft including MHV and some portion of the left medial segment is one of them [8]. It could be an ideal operative method for recipients but it can cause adverse effects on donor safety related to congestion of the remnant left lobe. The other method to prevent graft congestion is LDLT using MRL graft with reconstruction of MHV. This operative method was recognized as the best way for donor safety and to get an adequate functional graft for recipient safety [6,10].

However, LDLT using conventional MRL graft might raise concerns about technical difficulty to perfectly reconstruct the many branches of V5 and V8 and to maintain patency, especially in inexperienced teams. There could be debate in decision making for outflow reconstruction for anterior segment that would be guided by, such as, vessel size, congestion volume, and ultrasound finding. Additionally, a cryopreserved vessel graft is not commonly available in most transplantation centers. To overcome these concerns, several kinds of the modified extended right lobe (MERL) graft were introduced [7,11,12].

Hwang et al. [12] suggested a kind of MERL graft that was procured by tailoring transection of V5 for optimal sharing of MHV in RL donor. They designed this transection plane because multiple V5 would be met at the liver cut surface in one third of living donors. And, they insisted that this type of RL graft protects all of V4b and half of major V4a branches regardless of V4 anatomy. This type graft could be applicable in GRWR in less than 1% amount of hepatic vein congestion, more than 30% of RL graft, remnant liver volume greater than 35% of total liver volume, and multiple sizable V5. They also described that parenchymal transection line was one to two cm apart from the demarcation line to the left and so a devitalized small portion of the medial segment parenchyma was excised from the RL graft in 2 cases among all 3 cases. In contrast with their experiences, our parenchymal transaction line was exactly same with the demarcation line. And our MERL graft such as CMPRL graft was safely procured from all 37 donors from December 2011.

Toshima et al. [7] proposed another kind of MERL graft named as V5 drainage preserved right lobe graft (VP-RL). They classified anatomic variations of V4 into 3 types: V4 inferior dominant type (type A); V4 superior dominant type (type B); umbilical vein dominant type from left hepatic vein (type C). They analyzed the functional liver remnant volume (FLRV) of each V4 anatomic types between VP-RL graft using group and MRL graft using group by simulation study. As a result, type A showed significantly lower FLRV when using VP-RL graft compared with MRL graft, and thus concluded that VP-RL graft should not be performed on donors with type A to obtain donor safety after donation. In their actual LDLT application of VP-RL, they concluded VP-RL graft group (n = 8) was superior to MRL graft group (n = 7). Unlike their concerns, partial congestion of remnant liver was observed mainly in V4a dominant types but it was a relatively small area and recovered within one month in our study. And postoperative course of type A donors were not significantly different with that of types B and C donors. Based on our experiences, CMPRL graft could be carefully applicable in most donors who had a remnant liver volume greater than 30% of whole liver with minimal fatty change. Additionally, one large V5 orifice was always obtained in CMPRL graft. Consequently, bench work came to be simplified and ischemic time was significantly shortened. Furthermore, this procedure may decrease the stricture rate of V5 anastomosis site and the rate of stent insertion for MHV reconstruction site. And in terms of maintenance of V5 patency, we determined that it was more favorable than conventional MRL graft.

In conclusion, LDLT using CMPRL graft is relatively safe procedure for live liver donors, and there are many benefits such as decrease of operation and ischemic time, convenience of operation, and more favorable maintenance of V5 patency. Donors with any type of V4 could be proper candidates for CMPRL graft if remnant liver volume is greater than 30% with minimal fatty change.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1After hepatic parenchyma dissection was performed, left side of caudal middle hepatic vein trunk and right side of cranial middle hepatic vein trunk were fully exposed. We transected middle hepatic vein tributary draining segment 4a vein (V4a) and get a single large orifice of middle hepatic vein tributary draining segment 5 vein (V5). Arrows indicate transection lines. |

| Fig. 2In bench work, a single large orifice of caudal middle hepatic vein trunk (arrow) was anastomosed with a ringed Gore-Tex graft in end-to-end fashion and segment 8 vein (V8) was anastomosed in end-toside fashion. |

| Fig. 3Comparison of serial postoperative AST (A), ALT (B), total bilirubin (C), and PT (D) between conventional modified right lobe group (group A) and caudal middle hepatic vein trunk preserved right lobe group (group B). |

| Fig. 4Comparison of serial postoperative AST (A), ALT (B), total bilirubin (C), and PT (D) between V4a dominant drainage group (group B1) and the other group (group B2). |

Table 1

Donor results: comparison between conventional modified right lobe group (group A) and caudal middle hepatic vein trunk preserved right lobe group (group B)

Table 2

Donor results: comparison between V4a dominant drainage group (group B1) and the other group (group B2)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Pusan National University Hospital Clinical Research Fund of 2012.

References

1. Chen CL, Fan ST, Lee SG, Makuuchi M, Tanaka K. Living-donor liver transplantation: 12 years of experience in Asia. Transplantation. 2003; 75:3 Suppl. S6–S11.

2. Maetani Y, Itoh K, Egawa H, Shibata T, Ametani F, Kubo T, et al. Factors influencing liver regeneration following living-donor liver transplantation of the right hepatic lobe. Transplantation. 2003; 75:97–102.

3. Lee S, Park K, Hwang S, Lee Y, Choi D, Kim K, et al. Congestion of right liver graft in living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2001; 71:812–814.

4. Inomata Y, Uemoto S, Asonuma K, Egawa H. Right lobe graft in living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2000; 69:258–264.

5. Sugawara Y, Makuuchi M, Sano K, Imamura H, Kaneko J, Ohkubo T, et al. Vein reconstruction in modified right liver graft for living donor liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2003; 237:180–185.

6. Lee SG, Park KM, Hwang S, Kim KH, Choi DN, Joo SH, et al. Modified right liver graft from a living donor to prevent congestion. Transplantation. 2002; 74:54–59.

7. Toshima T, Taketomi A, Ikegami T, Fukuhara T, Kayashima H, Yoshizumi T, et al. V5-drainage-preserved right lobe grafts improve graft congestion for living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2012; 93:929–935.

8. Lo CM, Fan ST, Liu CL, Wei WI, Lo RJ, Lai CL, et al. Adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation using extended right lobe grafts. Ann Surg. 1997; 226:261–269.

9. Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL. Technical refinement in adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation using right lobe graft. Ann Surg. 2000; 231:126–131.

10. Lee S, Park K, Hwang S, Kim K, Ahn C, Moon D, et al. Anterior segment congestion of a right liver lobe graft in living-donor liver transplantation and strategy to prevent congestion. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2003; 10:16–25.

11. Cho EH, Suh KS, Lee HW, Shin WY, Yi NJ, Lee KU. Safety of modified extended right hepatectomy in living liver donors. Transpl Int. 2007; 20:779–783.

12. Hwang S, Lee SG, Choi ST, Moon DB, Ha TY, Lee YJ, et al. Hepatic vein anatomy of the medial segment for living donor liver transplantation using extended right lobe graft. Liver Transpl. 2005; 11:449–455.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download