Abstract

Contrary to metastatic tumors of the omentum, primary tumors of the omentum are very rare. A 10-year-old girl presented with low abdominal pain. Imaging studies showed a multiseptated hemorrhagic tumor. The mass from the omentum was removed completely and confirmed as a malignant rhabdoid tumor. Despite aggressive chemotherapy, she died after 9 months due to disease progression. We report one case of primary malignant rhabdoid tumor of the omentum for the first time.

Contrary to metastatic tumors of the omentum, primary tumors of the omentum are very rare and sporadically reported [1]. The pathologic spectrum of the omentum varies from lipoma, liposarcoma, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, teratoma, fibrosarcoma, haemangiopericytoma, spindle cell sarcoma, desmoid tumor, fibroma, mesothelioma, etc. [2,3]. However, a primary malignant rhabdoid tumor in the omentum is very rare. Malignant rhabdoid tumors are highly aggressive tumors usually presenting in the central venous system, kidney and soft tissue in children. Herein, we present one case of primary malignant rhabdoid tumor of omentum in a 10-year-old girl for the first time.

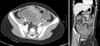

A 10-year-old girl visited the Emergency Department for abdominal pain. The pain had developed 7 days prior after getting hit with a ball. There were no associated symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. On physical examination, the patient complained of tenderness in the lower abdomen. Laboratory findings showed that hemoglobin was 10.8 g/dL and C-reactive protein was 8.06 mg/dL. Other results were not remarkable. Ultrasonography showed a multiseptated large hematoma. A computed tomography scan was undertaken and showed a lobulating hemorrhagic tumor (9 cm × 6 cm × 6.5 cm) with hemoperitoneum in the lower abdomen and pelvis (Fig. 1). Initially, the mass was suspected as a hematoma resulting from bleeding of the lymphangioma or hemangioma in the mesentery. After 3 days of antibiotics treatment, her pain was relieved. For follow-up, we examined the mass by ultrasonography. It revealed a necrotic solid tumor enhancing with peripheral vessels and a small amount of hemoperitoneum. We assumed that the mass was a malignant tumor of the mesentery or retroperitoneum, and performed a laparoscopic exploration. There was a huge omental solid mass that was freely movable and free of adhesions to any other intra-abdominal organs. The mass was removed completely including remnant omentum via laparotomy. Several seeding nodules were found on the small bowel mesentery and Pouch of Douglas and were removed for pathologic confirmation.

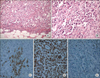

Grossly resected multinodular solid masses showed irregular and infiltrative borders and the cut surface was tan gray and fleshy. There was multifocal hemorrhages and necrosis (Fig. 2). Microscopically nested round to polygonal tumor cells revealed infiltrative borders (Fig. 3A) and each tumor cell showed eccentric nuclei, prominent nucleoli, as well as a characteristic eosinophilic inclusion or globules in the abundant cytoplasm (Fig. 3B). These findings were consistent to that of "rhabdoid" cells. Immunohistochemically neoplastic cells expressed cytokeratin (Fig. 3C), vimentin (Fig. 3D), and epithelial membrane antigen. However, tumor cells showed negative reaction for desmin, smooth muscle actin and myosin. Importantly neoplastic cells revealed the absence of nuclear expression of INI 1 (Fig. 3E), which was recently discovered as a one of the most important histologic markers of malignant rhabdoid tumors [4].

Postoperatively, she recovered uneventfully and resumed her oral diet on the 3rd postoperative day. An fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography was undertaken and revealed no evidence of primary malignancy including kidney and central nervous system. At postoperative day 7, the patient began chemotherapy consisting of VDC/IE (VCR, Doxorubicin, Cyclophosphamide/Ifosfamide, Etoposide) regimen. Despite 4 cycles of chemotherapy of VDC/IE regimen, the mass in the Pouch of Douglas, where previously there had been documented seedings, was now apparent and showed peritoneal carcinomatosis through magnetic resonance imaging. She had been treated with intensive chemotherapy yet died after 9 months due to disease progression.

The omentum is a double layer of the peritoneum that encloses an organ and connects it to the abdominal wall. The greater omentum is a fat-laden fold of peritoneum that hangs down from the greater curvature of the stomach and connects the stomach with the diaphragm, spleen, and transverse colon. Because of its location and wideness, the greater omentum could be a common site for metastatic tumors from intra-abdominal organs. In contrast, primary tumors originating from the omentum are very rare. The omentum has abundant fat with connective tissues such as arteries, veins, and lymphatics. The omentum is lined by double-layered mesothelial cells with stroma containing fibroblast, pericytes, lipocytes, and lymphoreticular bodies [5]. It can lead to various primary tumors. Among them, common benign tumors known to develop are lipoma, leiomyomas, teratoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, and fibromas. The most common malignant lesions are leiomyosarcomas, hemangiopericytomas, and fibrosarcomas [5].

In general, the symptoms of omental tumors present as abdominal discomfort (45.5%), abdominal mass (34.9%), and abdominal distention (15.2%) [5]. Unfortunately, there are no specific findings differentiating the origin or nature of the mass in imaging studies due to the extent of the omentum and the adhered organs. A considerable finding is displacement of the stomach, the transverse colon and small bowel, by an extrinsic mass. As presented in our case, the origin of the mass could not be identified preoperatively, and it was confirmed by surgical exploration. The treatment of omental tumors are complete excision via omentectomy. We diagnosed the mass as a malignant rhabdoid tumor based on the typical cellular morphology and immunohistochemical stains.

Rhabdoid tumor of the kidney was identified as a variant neoplasm of Wilms' tumor in 1978 [6]. Malignant rhabdoid tumors mainly occur in the kidney, soft tissue and central nervous system, but tumors have been reported in tongue, nasopharynx, neck, mediastinum, thymus, heart, uterus, urinary bladder, vulva, skin, soft tissue, paravertebral region, liver, and gastrointestinal tract [6-8]. They occur either in infancy or early childhood and generally have a dismal prognosis compared to other pediatric cancers. The malignancy has a high tendency to metastasize early and outcome is poor despite surgery and chemotherapy. The published survival rates have ranged from 5 days to 5 months. The "rhabdoid" is thus named as it resembles a rhabdomyosarcoma microscopically although it does not show skeletal muscle markers [6-10]. The rhabdoid cells shows round to teardrop shape with vesicular nuclei and a single large nucleolus. There are ill-defined round to oval hyaline inclusions composed of intermediate filaments in cytoplasm [1]. Immunohistochemically, the rhabdoid cells express both cytokeratin and vimentin, but not myogenic differentiation nor INI1 protein [4,7,8]. The presence of a mutation of the hsNF5/INI1 gene located at chromosome 22q11 is helpful in establishing the diagnosis [6,9]. For treatment, an aggressive operation to achieve total resection is recommended, because the effectiveness of chemoradiotherapy has not been proven. The classic combination of ifosfamide, carboplatinum and etoposide is recommended, and multidrug protocols including topoisomerase I inhibitors are recommended [10].

Our patient showed a malignant tumor on the omentum with peritoneal seeding. The biology of rhabdoid tumors are, unfortunately, very aggressive. Rhabdoid masses in the omentum have the potential to spread diffusely and easily to the peritoneal cavity, which results in a poor prognosis, despite aggressive chemotherapy.

The diagnosis of tumors in the omentum is very difficult and requires confirmation by excision and histologic evaluation. A primary tumor originating in the ometum is rare but possible even as a malignant tumor. The prognosis depends mainly on tumor biology yet the malignancy of the omentum might cause severe outcomes because these masses can easily metastasize to mesentery and peritoneum tissues.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1The computed tomography scan showed lobulating contoured hemorrhagic necrotic tumor (9 cm × 6 cm × 6.5 cm) with peripheral irregular enhancement in lower abdomen and pelvis and some amount of hemoperitoneum in cul-de-sac. |

| Fig. 2On formalin-fixed specimen, multinodular solid masses showed tan gray and fleshy cut surface. Multifocal hemorrhage and necrosis were seen. |

| Fig. 3Microscopic findings: tumor cells showed characteristic findings of "rhabdoid" cells such as infiltrative border (A: H&E, ×200), eccentric nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and characteristic eosinophilic inclusion or globules in abundant cytoplasm (B: H&E, ×400) in nested tumor cells. Immunohistochemically neoplastic cells expressed cytokeratin (C, ×400), and vimentin (D, ×400). Importantly neoplastic cells revealed absence of nuclear expression of INI 1 (E, ×200). |

References

1. Ishida H, Ishida J. Primary tumours of the greater omentum. Eur Radiol. 1998; 8:1598–1601.

2. Haaga JR. The peritoneum and mesentery. In : Haaga JR, Lanzieri CF, editors. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of the whole body. St. Louis: Mosby;1994. p. 1244–1291.

3. Sompayrac SW, Mindelzun RE, Silverman PM, Sze R. The greater omentum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997; 168:683–687.

4. Sigauke E, Rakheja D, Maddox DL, Hladik CL, White CL, Timmons CF, et al. Absence of expression of SMARCB1/INI1 in malignant rhabdoid tumors of the central nervous system, kidneys and soft tissue: an immunohistochemical study with implications for diagnosis. Mod Pathol. 2006; 19:717–725.

5. Evans KJ, Miller Q, Kline AL. Solid omental tumors [Internet]. New York: WebMD LLC;c1994-2013. cited 2011 Nov 28. Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/193622.

6. Reinhard H, Reinert J, Beier R, Furtwangler R, Alkasser M, Rutkowski S, et al. Rhabdoid tumors in children: prognostic factors in 70 patients diagnosed in Germany. Oncol Rep. 2008; 19:819–823.

7. Leong FJ, Leong AS. Malignant rhabdoid tumor in adults: heterogenous tumors with a unique morphological phenotype. Pathol Res Pract. 1996; 192:796–807.

8. Amrikachi M, Ro JY, Ordonez NG, Ayala AG. Adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract with prominent rhabdoid features. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2002; 6:357–363.

9. Chung CJ, Cammoun D, Munden M. Rhabdoid tumor of the kidney presenting as an abdominal mass in a newborn. Pediatr Radiol. 1990; 20:562–563.

10. Hilden JM, Meerbaum S, Burger P, Finlay J, Janss A, Scheithauer BW, et al. Central nervous system atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor: results of therapy in children enrolled in a registry. J Clin Oncol. 2004; 22:2877–2884.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download