Abstract

Purpose

Laparoscopic splenectomy (LS) for pediatric chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) patients has recently become widespread. However, its long-term result is rarely reported in children.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed the patients who underwent LS for pediatric chronic ITP from June 1998 to April 2007.

Results

There were 18 patients (14 male and 4 female) with mean age 9.5 ± 3.8 years. 14 complete response, 3 partial response, and 1 no response were occurred. During the 82-month median follow-up period, 9 patients maintained in a remission state without any additional treatment, and 9 patients relapsed. In a comparative analysis of the relapse group and no relapse group, hospital stays were longer in the relapse group and the preoperative platelet counts and platelet counts at 1 month post were lower in relapse group. A relapse-free survival among 17 patients who achieved partial or complete responses following LS showed 76.5%, 61.8%, and 33.0% at 1-, 5-, and 10-year following LS, respectively.

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is a common autoimmune hematologic disorder that requires splenectomy in its medically chronic state [1,2]. Laparoscopy has been widely accepted for various intra-abdominal surgeries. Since laparoscopic splenectomy (LS) was first reported in adults [3] and children [4], it has been adopted as the gold standard treatment [5] for various hematologic diseases in both pediatric patients and adults. Although various reports regarding the safety and feasibility of LS for ITP exist, reports of long-term follow-up results are reported in only a few reports, especially in pediatric patients. In this study, we evaluated the long-term results of LS for pediatric ITP patients and aimed to determine the differences between the remission group and the relapse group.

The Institutional Review Board of Yeouido St. Mary's Hospital approved our study and data collection. We retrospectively analyzed the clinical records and follow-up data of patients who underwent LS for pediatric chronic ITP from June 1998 to April 2007 at the Department of Surgery, Yeouido St. Mary's Hospital. All the patients were diagnosed with ITP between 0 and 15 years of age, and at least 12 months had passed since their diagnosis. Patients with a follow-up duration of less than 12 months and other hematologic diseases were excluded. A total of 24 pediatric ITP patients underwent LS during the study period. Among them, 6 were excluded: 4 because of insufficient follow-up duration and 2 because of concurrently diagnosed systemic lupus erythematosus.

The patients' age, sex, time from diagnosis to LS, intraoperative findings, hospital stay following LS, days before resuming diet, platelet count before operation, preoperative treatment, number of intravenous immunoglobulin G (IVIG) treatments, follow-up platelet counts 1, 2, and 3 days after LS and 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after LS were collected retrospectively.

Responses following LS were assessed according to the following definitions of response to ITP treatment in the American Society of Hematology's 2011 evidence-based practice guideline for ITP [6]; complete response (CR): a platelet count of 100 × 109/L measured on 2 occasions >7 days apart and the absence of bleeding; partial response (PR): a platelet count ≥30 × 109/L and a greater than 2-fold increase in platelet count from baseline measured on 2 occasions >7 days apart and the absence of bleeding; no response (NR): a platelet count <30 × 109/L or a less than 2-fold increase in platelet count from baseline or the presence of bleeding. Platelet counts must be measured on 2 occasions more than a day apart; loss of CR: a platelet count <100 × 109/L measured on 2 occasions more than a day apart and/or the presence of bleeding; loss of PR: a platelet count <30 × 109/L or a less than 2-fold increase in the platelet count from baseline or the presence of bleeding. Platelet counts must be measured on 2 occasions more than a day apart. Response evaluations were performed at 1 month postoperation.

Relapse following splenectomy was defined when the patient showed NR to LS or when a loss of response after CR or PR was developed.

Under general anesthesia, LS was performed using a standardized technique with four trocars with a right lateral decubitus position and the head up at 30 to 45 degrees. The inflation pressures were set at 8 to 12 mmHg.

In brief, the gastrosplenic, splenocolic, and splenodiaphragmatic ligaments were dissected, and the splenic hilum vessels were secured using 5-mm open loops and 5- or 10-mm hemoclips. The splenocolic and gastrosplenic ligaments, omentum, and paraduodenal area were always checked for accessory spleens.

According to the postoperative management protocol of our institution, sips of water started at postoperative 1st day. Then liquid diet and soft diet were proceeded at postoperative 2nd and 3rd day, respectively. Discharge was decided at postoperative 6th day according to patients' condition and wound status.

All continuous variables are described as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed using Student t-test. For categorical data, chi-squared or Fisher exact tests were used in univariate analyses. The patients' relapse-free survival was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. SPSS ver. 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform statistical analyses, and a P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The baseline characteristics of the included patients are described in Table 1. The mean age of the patients (14 males and 4 females) was 9.5 ± 3.8 years old. The patients underwent LS after a mean of 38.7 months following the diagnosis of ITP. All of the patients underwent steroid and IVIG treatment before LS. The mean number of IVIG treatments was 3.4 ± 1.8. The mean preoperative platelet count was 20.7 × 109 ± 19.6 × 109/L. The mean operation time was 138.3 ± 50.1 minutes. A liquid diet was resumed after an average of 2.1 ± 0.5 days, and the mean hospital stay after LS was 6.3 ± 2.2 days. Among the 18 patients, 7 had accessory spleens that were removed successfully with laparoscopy. According to the response evaluation following treatment in ITP patients evaluated 1 month postoperation, there were 14 cases (77.8%) of CR, 3 cases (16.7%) of PR, and 1 case (5.6%) of NR. During the 82-month median follow-up period (range, 12 to 159 months), 9 patients maintained a remission state without any additional treatment, and 9 relapsed. All of the PR patients relapsed, and 5 out of 14 CR patients (35.7%) relapsed. All of the relapsed patients had a damaged RBC scan, and accessory spleens were found in 2 patients. Laparoscopic accessory splenectomy was performed in those 2 patients; the others underwent steroid treatments alone or IVIG treatment. One patient achieved CR following laparoscopic accessory splenectomy. The other patient achieved response, but relapsed 5 years later.

Univariate comparative analysis was performed for the relapse group and nonrelapse group (Table 2). Median follow-up period for nonrelapse group and relapse group are 55 and 11 months, respectively. No between-group differences were found for sex, age, time to splenectomy from diagnosis, operation time, diet resumption, spleen size, and spleen weight. However, the hospital stay was longer for relapse group (5.2 ± 1.1 vs. 7.4 ± 2.6, P = 0.029). The perioperative platelet count, preoperative platelet count and postoperative platelet count after 1 month were lower in the relapse group; however, the platelet count immediately after LS showed no difference between the two groups.

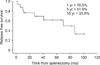

A relapse-free survival analysis was performed among the 17 patients who achieved a PR or CR following LS (Fig. 1). The 1-, 5-, and 10-year relapse-free survival rates were 76.5%, 61.8%, and 33.0%, respectively.

ITP is characterized by isolated thrombocytopenia in the absence of definite and specific precipitants. Initial treatment is focused on steroid therapy or immunoglobulin infusion. Splenectomy is recommended for children and adolescents with chronic or persistent ITP who have significant or persistent bleeding and a lack of response to or intolerance of other therapies, such as corticosteroids, IVIG, and anti-D and/or those who have a need for an improved quality of life [6]. Most reports of the long-term results for ITP address adult patients and conventional open splenectomy. Reid [7] reported the remission of 29 patients (85%) among 34 adult chronic ITP patients who underwent splenectomy. Stasi et al. [8] reported a Kaplan-Meier plot of disease-free survival duration for patients who attained a complete remission following splenectomy; in that study, the 24-, 48-, and 72-month survival rates were 72.9%, 66.6%, and 66.6%, respectively. Recently, Wang et al. [9] reported a 76.1% long-term response rate for LS in adult chronic ITP patients.

The long-term clinical course of pediatric ITP is variable. The reported rate of spontaneous CR with or without any treatment ranges from 44% to 85% [7,10,11,12]. There are few reports regarding the result of splenectomy itself, especially LS in pediatric patients. Bansal et al. [10] reported that the estimated 5-year remission rate of 270 pediatric ITP patients who received some form of treatment was 30%; the 10-year rate was estimated at 44%. In that report, splenectomy was performed in 18 patients, 9 of whom achieved CR. Our study found similar results. However, Bansal et al. [10] did not mention precise recurrence patterns following splenectomy. In our study, a total of 18 pediatric chronic ITP patients were included. 17 patients showed an initial response to LS at 1 month postoperation. However, 8 patients relapsed at a median of 19 months (range, 2 to 87 months) after LS. In addition, the 5-year relapse-free survival rate was 61.8%, and the 10-year relapse-free survival rate was 33.0%. These results showed higher rates of initial response up to 5 years later and indicates the possibility of relapse as late as 70 and 86 months after LS.

In the comparison between the relapse group and nonrelapse group, hospital stays were longer for the nonrelapse group. This difference was caused by the hospital stay of two patients. One was a nonresponse patient who required additional medical treatment following LS; the other patient had an extended hospital stay because of wound infection at the spleen removal site.

Perioperative platelet count showed significant differences between the two groups. The preoperative platelet count was significantly lower in the relapse group. Immediately postoperation, the platelet count was remarkably increased and showed no differences between groups. However, significant differences emerged at 1 month post-LS. In Wang et al. [9]'s study of adults, the difference in the perioperative platelet counts of response and nonresponse groups was analyzed, and the postoperative platelet count was significantly lower in the nonresponse group. We suggest that the cause of such changes could be related to the pathogenesis of chronic ITP.

The pathogenesis of chronic ITP is described with two components. One is the increased platelet destruction, the other is the decreased platelet production. In addition, the destructive component includes two mechanisms: platelet auto-antibody-mediated destruction, which usually occurred in the reticuloendothelial system (especially at the spleen), and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated platelet lysis [13]. The spleen is considered the primary site of platelet destruction and an important site for antiplatelet antibody production [14]. Although the spleen has the most important role in the pathogenesis of chronic ITP, it is not the entire mechanism responsible for chronic ITP. For this reason, remission occurred in the early postoperative period; however, the number of relapsed patients gradually increased. Changing patterns of postoperative platelet counts indicate that splenectomy effects are dominant in both groups. However, from 1-month postoperation, the splenectomy effect is diluted and other destructive mechanisms, such as T-cell-mediated platelet lysis and/or decreased platelet production, could become dominant components of pathogenesis.

Although accessory spleen can play a role in relapse, it is only part of the cause. In our cases, all relapsed patients underwent damaged RBC scans, and accessory spleens were found in 2 patients. Laparoscopic accessory splenectomy was performed in these 2 patients, and the others underwent steroid treatment alone or IVIG treatment. One patient achieved CR following laparoscopic accessory splenectomy. The other patient achieved a response, but relapsed 5 years later. Seven out of 18 patients had accessory spleens, and those were completely resected using laparoscopy. Among the 7 patients who had accessory spleens at the initial surgery, 4 relapsed and showed no abnormal accessory spleen on the damaged-RBC scan.

In addition, this type of ITP reactivation can occur any time after splenectomy, even after as long as 5 years. Systematic reviews reported a response rate after splenectomy ranging from 66% to 72% after a 5-year follow-up [15,16]. Follow-up for ITP relapse should be conducted to clarify the long-term response following splenectomy.

Our study has several limitations. This is retrospective study with a very small sample size. However, long-term follow-up results following LS for pediatric chronic ITP patients in a single institution are very rare.

In conclusion, LS in pediatric chronic ITP patients achieved excellent results immediately after surgery. However, during the long-term follow-up period, disease relapse can occur at any time after LS. These findings alert physicians to perform careful follow-up even when patients have achieved a CR for several years.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Relapse-free survival of 17 pediatric chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura patients who achieved complete response following laparoscopic splenectomy.

References

1. Cines DB, Blanchette VS. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:995–1008.

2. McMillan R. Chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med. 1981; 304:1135–1147.

3. Delaitre B, Maignien B. Splenectomy by the laparoscopic approach. Report of a case. Presse Med. 1991; 20:2263.

4. Tulman S, Holcomb GW 3rd, Karamanoukian HL, Reynhout J. Pediatric laparoscopic splenectomy. J Pediatr Surg. 1993; 28:689–692.

5. Friedman RL, Fallas MJ, Carroll BJ, Hiatt JR, Phillips EH. Laparoscopic splenectomy for ITP. The gold standard. Surg Endosc. 1996; 10:991–995.

6. Neunert C, Lim W, Crowther M, Cohen A, Solberg L Jr, Crowther MA, et al. The American Society of Hematology 2011 evidence-based practice guideline for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2011; 117:4190–4207.

7. Reid MM. Chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: incidence, treatment, and outcome. Arch Dis Child. 1995; 72:125–128.

8. Stasi R, Stipa E, Masi M, Cecconi M, Scimo MT, Oliva F, et al. Long-term observation of 208 adults with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Med. 1995; 98:436–442.

9. Wang M, Zhang M, Zhou J, Wu Z, Zeng K, Peng B, et al. Predictive factors associated with long-term effects of laparoscopic splenectomy for chronic immune thrombocytopenia. Int J Hematol. 2013; 97:610–616.

10. Bansal D, Bhamare TA, Trehan A, Ahluwalia J, Varma N, Marwaha RK. Outcome of chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010; 54:403–407.

11. Jayabose S, Levendoglu-Tugal O, Ozkaynkak MF, Visintainer P, Sandoval C. Long-term outcome of chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in children. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004; 26:724–726.

12. Tamary H, Kaplinsky C, Levy I, Cohen IJ, Yaniv I, Stark B, et al. Chronic childhood idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura: long-term follow-up. Acta Paediatr. 1994; 83:931–934.

13. Nugent D, McMillan R, Nichol JL, Slichter SJ. Pathogenesis of chronic immune thrombocytopenia: increased platelet destruction and/or decreased platelet production. Br J Haematol. 2009; 146:585–596.

14. Ghanima W, Godeau B, Cines DB, Bussel JB. How I treat immune thrombocytopenia: the choice between splenectomy or a medical therapy as a second-line treatment. Blood. 2012; 120:960–969.

15. Kojouri K, Vesely SK, Terrell DR, George JN. Splenectomy for adult patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a systematic review to assess long-term platelet count responses, prediction of response, and surgical complications. Blood. 2004; 104:2623–2634.

16. Mikhael J, Northridge K, Lindquist K, Kessler C, Deuson R, Danese M. Short-term and long-term failure of laparoscopic splenectomy in adult immune thrombocytopenic purpura patients: a systematic review. Am J Hematol. 2009; 84:743–748.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download