Abstract

Purpose

Recently many cases of appendectomy have been conducted by single-incision laparoscopic technique. The aim of this study is to figure out the benefits of transumbilical single-port laparoscopic appendectomy (TULA) compared with conventional three-port laparoscopic appendectomy (CTLA).

Methods

From 2010 to 2012, 89 patients who were diagnosed as acute appendicitis and then underwent laparoscopic appendectomy a single surgeon were enrolled in this study and with their medical records were reviewed retrospectively. Cases of complicated appendicitis confirmed on imaging tools and patients over 3 points on the American Society of Anesthesia score were excluded.

Results

Among the total of 89 patients, there were 51 patients in the TULA group and 38 patients in the CTLA group. The visual analogue scale (VAS) of postoperative day (POD) #1 was higher in the TULA group than in the CTLA group (P = 0.048). The operative time and other variables had no statistical significances (P > 0.05).

Conclusion

Despite the insufficiency of instruments and the difficulty of handling, TULA was not worse in operative time, VAS after POD #2, and the total operative cost than CTLA. And, if there are no disadvantages of TULA, TULA may be suitable in substituting three-port laparoscopic surgery and could be considered as one field of natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery with the improvement and development of the instruments and revised studies.

Compared to conventional type of surgery, like laparotomy, minimally invasive surgery causes less pain and scarring and requires less amount of analgesic. Consequently, it bears early ambulation, fast start to regular diet and short hospitalization days [1-8]. Moreover, its minor manipulation and irritation to operation site reduces the incidence of postoperative adhesions [1-3]. During the past 10 years, laparoscopic surgery has advanced to less invasive methods such as single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) or natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) through the development of operation technology and instruments [9].

Since 1894, when open appendectomy procedure was first attempted by McBurney [10], it has taken 100 years for the implementation of laparoscopic appendectomy by Semm [11]. However, the latest changes are amazingly fast. Single port laparoscopic appendectomy was started in 1992 [12], and recently, studies about procedures using transumbilical incision have evolved [13-15]. Even though transumbilical laparoscopic appendectomy (TULA) has many advantages such as less scarring and less postoperative pain, it still possesses several disadvantages. First of all, the movement of the equipment is limited due to the number of ports, and limitations in using the most favorable instruments for complexity and technical challenges of the procedure [16].

We wondered that in spite of these disadvantages, TULA could substitute conventional three-port laparoscopic appendectomy (CTLA). Thus, the aim of this study is to compare TULA with CTLA and then to figure out the advantages and disadvantages of TULA procedure.

The study was conducted with patients who were diagnosed with acute appendicitis and underwent laparoscopic appendectomy in Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital between the years 2010 and 2012. The routine preoperative examinations included complete medical and surgical history taking, physical examination, laboratory blood count and blood biochemistry analysis, abdominal ultrasonography (USG) or abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT). Right after diagnosis of acute appendicitis, the patients were injected with Ceftriaxone 2 g (ceftriaxone sodium 2 g/btl, Boryung Pharm Co., Seoul, Korea) affiliated with 3rd generation cephalosporin, and were given antibiotics till postoperative day (POD) #5. The patient groups that were defined as grossly gangrenous type postoperatively, were injec ted with Trizele 500 mg (metronidazole 500 mg/100 mL, Choowae Pharma Co., Seoul, Korea) every 8 hours, addi tionally, until POD #3. When discharged before POD #3 or POD #5, intravenous antibiotics were given right before lea ving.

Since patients with severe systemic disease have more susceptibility and different postoperative analgesics washout rates due to their impaired hepatic or renal function, the individuals with an American Society of Anesthesia (ASA) physical status classification system points greater than 3 were excluded from the study. Furthermore, when we started the method of TULA initially, the cases of complicated appendicitis with perforation or periappendiceal abscesses were not indicated because of the concern that those procedures may induce longer operative times. Instead, cases of complicated appendicitis were implemented by CTLA or open appendectomy because they were not contraindicated. Excluding complicated appendicitis from the use of TULA is based in the fact that it could incur bias or inaccurate results due to its different operative duration, postoperative complication, and pain. Finally, 89 acute appendicitis patients were enrolled in the research, TULA was implemented on 51 of them and CTLA for the rest. The choice between the two operations was made after the patients and their guardians were thoroughly educated on details of the procedure using pictures. All of the operations were done by one surgeon.

First, the patient was subjected to general anesthesia and the left arm was placed next to the body after abducting it in the supine position. Before the skin drape, the umbilicus was cleansed with alcohol swabs and a betadine solution was applied from the nipple to the suprapubic area and was left out until it dried up; then proceeding with the preparation process. A vertical incision, about 1.5-2 cm, was made by pulling the umbilicus with the towel clip that opened up the peritoneum layer, as well as the fascia, after dissecting the subcutaneous layer - followed by checking the free space and the intra-abdominal cavity organ (Fig. 1). Instead of the recently manu factured single-port trocar, the Alexis wound retractor (Applied Medical, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA, USA) X-Small size were used for widening the incision site (Fig. 2). Then the wrist part of the surgical glove #6 was folded to cover the wound retractor and three holes were made on each of the three fingers to insert one 11 mm and two 5 mm of ENDOPATH XCEL trocars (Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA) which were tied and fixed with black silk (Fig. 3). Through the ENDOPATH XCEL trocar 11 mm, CO2 gas was infused and inflated the abdominal cavity to a pressure of 12 mmHg. The operating table was tilted to the Trendelenburg position associated with an up rotation to allow adequate exposition. A 10 mm flexible laparoscope camera (Olympus vicera LTF type V3; Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan) was inserted through the abdominal wall with the 11 mm trocar which was kept intact underneath the surgical glove and a 5 mm laparoscopic Harmonic Curved Shears (Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc.) was used to dissect the mesoappendix as well as the periappendiceal tissue. After the double ligation of the appendiceal base with a round Lap loop #1-0 (Sejong medical, Paju, Korea), the appendix was divided with the laparoscopic Harmonic Curved Shears. The resected appendix was placed into the un-holed finger of the surgical glove that was covering the wound retractor and it was tied with black silk to prevent contamination. The mucosa of the resected appendix stump was cauterized. The surgical glove and the wound retractor were removed and one layer interrupt suture was done to the peritoneum and fascia with a Vicryl Plus #1-0 (Ethicon Inc., Somerville, NJ, USA). The subcutaneous layer was repaired by an interrupt suture using Vicryl plus #3-0 (Fig. 4). Sufficient amounts of Terramycin OPH oint 3.5 g/tube (oxytetracycline hydrochloride 17.5 mg; polymyxin B sulfate 35,000 IU, Pfizer, New York, NY, USA) was applied and a gauze ball was placed to pack the umbilicus. A 10 cm × 12 cm size of Tegaderm Film was attached (3M Health Care, Neuss, Germany). Additionally, a 10 mL syringe needle was inserted through the skin to the gauze ball without piecing the Tegaderm Film to aspirate and vacuum the area around the gauze ball so the tissue near the umbilicus could tightly adhere to the ball.

In CTLA, the same preparation maneuver was used. After making a skin incision approximately 1.5 cm in size, as with TULA, marked skin was opened up to check the intra-abdominal cavity. Then, a purse-string suture was made on the peritoneum and fascia as one layer with Vicryl plus #1-0 and Auto Suture Blunt Tip trocar (Covidien Inc., Mansfield, MA, USA) 10 mm inserted. The abdominal cavity CO2 gas pressure was maintained at 12 mmHg by packing the gauze into the incision site and sealing up the abdominal cavity by tightening the purse-string suture. An ENDOPATH XCEL trocar of 10 mm was placed on the suprapubic area, an ENDOPATH XCEL trocar of 5 mm on about 2-finger medial side to left anterior superior iliac spine and then an appendectomy was conducted in the same manner. The resected appendix was placed into a small size Lap bag (Sejong medical) and then removed through the trocar insertion site on the infraumbilicus area together with the trocar to avoid wound contamination. After reinserting the removed trocar, the resected appendix stump was cauterized and all of the trocars were removed. The infraumbilical trocar site was tied with a purse-string suture, which had been implemented earlier, and dermal sutures with Vicryl plus #4-0 was done on each incision site followed by simple dressing. The umbilical wound of TULA, pictured at the operation room just after the surgery is on Fig. 4.

The following parameters were collected on the enrolled patients preoperatively: age, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), thickness of the abdominal walls, white blood cell (WBC) counts, neutrophil counts, C-reactive protein. There have been various methods for measuring abdominal wall thick ness measurements in other studies but no principal method for it [17-20]. In this study, the abdominal wall thickness was measured by abdominal and pelvic CT at the point located at 1 cm lateral to the umbilicus. The patients receiving USG instead of preoperative CT were excluded as missing values in the statistics.

Outcome variables that were used for comparing the efficacy between the two groups were operative time, time until gas-passing and starting diet, hospitalization days, cost of the surgery and treatment, visual analogue scale (VAS) on POD #1, maximum VAS from POD #2 until the day of discharge, intravenous analgesics dose after the surgery and histopathologic findings. The postoperative diet was started after confirmation of gas passing. Only Ketorac Injection (keto rolac tromethamine 30 mg/mL; Daewoo Pharm Co., Seoul, Korea) was used for postoperative pain control and patient-controlled analgesia was not used.

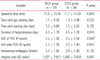

The average age of the 89 patients was 31 years (31.3 ± 14.63 years) and 40 of them were male and 49 of them female. TULA was conducted on 51 patients and CTLA on the other 38 patients. In TULA group, the mean age was 30.8 ± 13.23 years old and the male to female ratio was 1:1.83. In CTLA group, the mean age was 31.8 ± 16.50 years old and the male to female ratio was 1:0.73. The male to female ratio between the two groups showed statistically significant difference (P = 0.015) (Table 1).

Mean BMI of TULA group was 22.1 ± 3.62 kg/m2 and mean thickness of abdominal wall was 25.6 ± 6.88 cm. Meanwhile, mean BMI of CTLA group was 22.2 ± 3.24 kg/m2, mean thickness of the abdominal wall was 23.6 ± 8.68 cm. There was no statistically significant difference in the two variables (P > 0.05) (Table 1). Comparing the preoperative inflammation indicator, WBC of TULA group was 12,185 ± 4,713.2/µL, CRP was 2.7 ± 2.93 mg/dL, WBC of CTLA group was 11,582 ± 3,861.4/µL, CRP was 2.0 ± 2.35 mg/dL which showed no statistical differences (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Patients with a perforated type of acute appendicitis or appendicitis with periappendiceal abscess on the preoperative radiologic evaluation were excluded from the study. In fact, 10 patients in the TULA group and 12 patients in the CTLA group were found to have had a periappendiceal abscess from the postoperative histopathologic results. Minimal inflammation finding was observed in four patients in the CTLA group and nine in the TULA, and suppurative type of appendicitis was observed in 32 patients in TULA group and 22 in CTLA group (Table 2).

Mean operative time was 71.6 ± 23.55 minutes in TULA group, 71.7 ± 21.03 minutes in CTLA group. The mean POD until gas passing in TULA group was 1.1 ± 0.33, and starting of diet is on POD 1.2 ± 0.66 on average. Meanwhile, in the CTLA group, the mean POD until the passing of gas was 1.2 ± 0.58, and the starting of diet was POD 1.3 ± 0.52 on average. The average hospitalization days of TULA group was 4.3 ± 1.70 and 4.5 ± 1.29 with CTLA group. The mean operative time, the time until starting of diet and hospitalization days showed no statistical differences.

Immediately after the surgery, the VAS of the TULA group was 3.5 ± 1.30 on average and CTLA group 2.3 ± 0.58, which showed higher score in TULA group and was statistically significant (P = 0.048). However, a maximum VAS from POD #2 until the day of discharge, in TULA group was 2.2 ± 1.26 and 2.0 ± 1.00 in CTLA group. Also, there was no significant difference between the two groups. The hospital cost of TULA in US dollars was 1,527 ± 218.3 and CTLA was US dollars 1,549 ± 119.8, a not statistically significant difference (P = 0.048) (Table 3).

In this study, systematic complications were not checked, but wound complications were confirmed in two patients in TULA group. One of them had stitch abscess and the other had wound seroma. These wound infection cases got treated after conservative treatment through the out-patients department (P = 0.505) (Table 4).

McBurney [10] described open appendectomy in 1894. Since then, Semm [11] introduced laparoscopic appendectomy for the first time; compared to open appendectomy, laparoscopic appendectomy has less postoperative pain and lesser doses of analgesics. It also has not only less tissue injury but also less irritation of the intestines so that the results in reduction of adhesion may occur after the sugery. It enables early ambulation and food intake and a short hospitalization period. Thus, patients can return early to normal lives and also have less cosmetic problems after surgery. For these reasons, laparoscopic surgery is now widely performed [1-3]. And a variety of methods using single incision such as NOTES or hybrid NOTES have been performed. As this type of surgery is becoming more popular, various studies concerning it have been increasingly conducted.

NOTES which approaches into the abdominal cavity through the natural orifices such as the umbilicus, the stomach, the vagina, the bladder and the rectum reduces postoperative pain and enables a faster return to routine activity and better cosmetic outcome [21,22]. But for several reasons such as limited degrees of freedom of movement, number of ports, and limitation of optimal instruments for the complexity and technical challenges of the operation, 'pure' NOTES could not be applied freely for the operation. As a result, 'hybrid' NOTES or modified laparoscopic technique that use an additional port for approaching the abdominal cavity have been developed as a bridge procedure [21]. Additionally, studies on pure forms of NOTES have been conducted continuously as well [21,23-25].

Recently, not only overseas but also in Korea, the transumbilical approach has been tried for minimal scarring. According to a study conducted by Lee et al. [13], there are no differences in postoperative outcomes between a TULA and the conventional three-port laparoscopic approach. Other studies reported longer operative times and more doses of analgesics in patients who underwent TULA [14,15]. Especially, Lee et al. [14] figured out that postoperative wound infection increased significantly. Despite these disadvantages and controversies over the benefits, transumbilical single-port laparoscopic appen dectomy has been conducted continuously in the expectation of early recovery and desired cosmesis.

This study is based on the operative results of acute appendicitis treated surgically by a single well-trained surgeon. Especially, this approach minimized the possible biases by stratifying the data by the medical history, ASA score and preoperative imaging study.

First of all, a significant difference in the outcome was found between the different gender groups (P = 0.015), since the patients chose the method of surgery; TULA was performed more in females whose concerns were more about scaring, which reflects that TULA has an advantage regarding cosmetic concerns.

The mean operative time of TULA and CTLA were 71.6 minutes and 71.7 minutes respectively, which are nearly the same. This is quite different to the previous studies that showed TULA group's operative time at about 5-10 minutes longer than CTLA group's [26,27]. Even a study conducted by Kim et al. [28] presented about 15 minutes more of operative time in TULA group, which was statistically significant. TULA is expected to take more operative time than CTLA because it requires difficult surgical techniques due to a single surgical window, but it was actually not. The reason is that when a surgeon already skilled at CTLA executes TULA, the reduced number of trocars does not affect the operative time because the range of dissection is not broad and so the surgeons get used to the procedure fast. Also, setting up the 3 incisions for the trocars themselves in CTLA takes a long time. And with the development of SILS instruments, appendectomy and cholecystectomy executed in a localized space with those instruments can be implemented fast and easily.

VAS on POD #1 was significantly higher in TULA group (TULA group, 3.50 ± 1.30; CTLA group, 2.30 ± 0.58; P = 0.048), which was assumed that TULA requires longer fascia incision than CTLA, resulting in more wound stretching wound bundling due to the amount of equipment on only one incision. Park et al. [29] reported that in a single incision laparoscopic surgery for an appendectomy, immediate postoperative pain was more severe than in a conventional 3-port laparoscopic appendectomy. Usually, patients expect less pain in a less incision-required procedure. Therefore, the unexpected strong pain might contribute to the higher VAS. The VAS after POD #2 and total dose of postoperative intra venous analgesics did show no difference between the two groups.

Additionally, the gas passing, postoperative starting diet date, and total hospitalization days show no significant difference between the two groups leading to a similar hospital course in the two groups. Another study concerning single-port laparoscopic appendectomy also showed no significant difference in hospital course compared to CTLA [13-15,26-28], which might originate from the characteristics of appen dectomy procedure itself - a small incision, minimal bowel manipulations and irritation, early passing-gas and little pain. In this study, the hospital course was checked on a daily basis, but if checked on in fewer intervals, different results would have appeared.

The cost of the surgery and the treatment was US dollars 1,527 ± 218.3 in TULA group, and US dollars 1,549 ± 119.8 in CTLA group, which showed no statistical significance. (P = 0.547). According to the study conducted by Lee et al. [30], the cost was significantly lower in TULA group; this is because the instrument was made using slim pipes and trocar. In this study, 3 disposable trocars and one disposable wound retractor were used in the TULA group, which did not cause a higher total cost than the CTLA group on the use of instruments. TULA group did not use the X-Small size Alexis wound retractor because the resected appendix was placed into an un-holed finger of the surgical glove instead of using the small size Lap bag to prevent contamination, and also reduce the cost; and different trocars for cameras were used. Diff ering time under anesthesia due to different operative time also can be one of the causes for this lack of difference in cost. These days, many instruments and SILS port have been developed to improve surgical efficacy. Although there are negative aspects of surgical costs rising. Therefore, when con sidering the cost of SILS instruments, it might be better to use the above mentioned instruments rather than using commercialized disposable trocars.

In some of the previous studies, it has been reported that TULA procedure takes more operative time [26-28] and causes more pain postoperatively [14,15] than CTLA. However, there was no difference in operative time, hospitalization date after the surgery, and the cost of the surgery in this study. The patient might complain of more pain right after TULA than after CTLA. However, in terms of surgery efficiency, single port surgery could be equally good, and considering the cosmetic outcome of the surgery, it would be generally recommended for patients. As the development of the techniques and the instruments progress, increasing SILS' efficiency will be shown.

The main limitation of this research could be the small num ber of enrolled patients. Also, this research did not include any cases of complicated appendicitis. In order to do research more specifically regarding TULA's efficiency or indications, more information relating to complicated appendicitis cases should have been collected.

In conclusion, TULA had no disadvantages in comparison with CTLA in operative time, time of starting diet, intention of postoperative pain, postoperative complications, and hospital cost. Therefore, TULA could be a feasible alternative of CTLA for appendectomy. In order to make an improvement of the above mentioned limitations of this study, a randomized prospective study with a large number of patients is needed in the future.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Transumbilical incision. The umbilicus was retracted with the towel clips for a full exposure.

Fig. 2

A wound retractor was used to prevent from the wound contamination and to secure the space for equipment movement.

Fig. 3

Applied equipment for the single port. Three holes were made on the fingers of the surgical glove for the fixation of the 3 trocars. The remained finger parts of the glove were used to place the resected appendix.

Fig. 4

The umbilical wound of transumbilical laparoscopic appendectomy, pictured at the operation room just after the surgery.

References

1. Towfigh S, Chen F, Mason R, Katkhouda N, Chan L, Berne T. Laparoscopic appendectomy significantly reduces length of stay for perforated appendicitis. Surg Endosc. 2006. 20:495–499.

2. Khan MN, Fayyad T, Cecil TD, Moran BJ. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: the risk of postoperative infectious complications. JSLS. 2007. 11:363–367.

3. Golub R, Siddiqui F, Pohl D. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: a metaanalysis. J Am Coll Surg. 1998. 186:545–553.

4. Gupta A, Shrivastava UK, Kumar P, Burman D. Minilaparoscopic versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomised controlled trial. Trop Gastroenterol. 2005. 26:149–151.

5. Giday SA, Kantsevoy SV, Kalloo AN. Principle and history of Natural Orifice Translumenal Endoscopic Surgery (NOTES). Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2006. 15:373–377.

6. Wu C, Prachand VN. Reverse NOTES: a hybrid technique of laparoscopic and endoscopic retrieval of an ingested foreign body. JSLS. 2008. 12:395–398.

7. Buess GF. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2008. 17:329–330.

8. Arezzo A, Repici A, Kirschniak A, Schurr MO, Ho CN, Morino M. New developments for endoscopic hollow organ closure in prospective of NOTES. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2008. 17:355–360.

9. Kalloo AN, Singh VK, Jagannath SB, Niiyama H, Hill SL, Vaughn CA, et al. Flexible transgastric peritoneoscopy: a novel ap proach to diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in the peritoneal cavity. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004. 60:114–117.

10. McBurney C. IV. The incision made in the abdominal wall in cases of appendicitis, with a description of a new method of operating. Ann Surg. 1894. 20:38–43.

11. Semm K. Endoscopic appendectomy. Endoscopy. 1983. 15:59–64.

12. Pelosi MA, Pelosi MA 3rd. Laparoscopic appendectomy using a single umbilical puncture (minilaparoscopy). J Reprod Med. 1992. 37:588–594.

13. Lee J, Baek J, Kim W. Laparoscopic transumbilical single-port appendectomy: initial experience and comparison with three-port appendectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010. 20:100–103.

14. Lee SY, Lee HM, Hsieh CS, Chuang JH. Transumbilical laparoscopic appendectomy for acute appendicitis: a reliable one-port procedure. Surg Endosc. 2011. 25:1115–1120.

15. St Peter SD, Adibe OO, Juang D, Sharp SW, Garey CL, Laituri CA, et al. Single incision versus standard 3-port laparoscopic appendectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2011. 254:586–590.

16. Mintz Y, Horgan S, Cullen J, Stuart D, Falor E, Talamini MA. NOTES: a review of the technical problems encountered and their solutions. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008. 18:583–587.

17. Kim J, Lim H, Lee SI, Kim YJ. Thickness of rectus abdominis muscle and abdominal subcutaneous fat tissue in adult women: correlation with age, pregnancy, laparotomy, and body mass index. Arch Plast Surg. 2012. 39:528–533.

18. Butler M, Servaes S, Srinivasan A, Edgar JC, Del Pozo G, Darge K. US depiction of the appendix: role of abdominal wall thickness and appendiceal location. Emerg Radiol. 2011. 18:525–531.

19. Fuchs F, Houllier M, Voulgaropoulos A, Levaillant JM, Colmant C, Bouyer J, et al. Factors affecting feasibility and quality of second-trimester ultrasound scans in obese pregnant women. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013. 41:40–46.

20. Sugiura T, Uesaka K, Ohmagari N, Kanemoto H, Mizuno T. Risk factor of surgical site infection after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Surg. 2012. 36:2888–2894.

21. Chouillard E, Dache A, Torcivia A, Helmy N, Ruseykin I, Gumbs A. Single-incision laparoscopic appendectomy for acute appendicitis: a preliminary experience. Surg Endosc. 2010. 24:1861–1865.

22. Bergman S, Melvin WS. Natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2008. 88:1131–1148.

23. Palanivelu C, Rajan PS, Rangarajan M, Parthasarathi R, Senthilnathan P, Praveenraj P. Transumbilical endoscopic appendectomy in humans: on the road to NOTES: a prospective study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008. 18:579–582.

24. Palanivelu C, Rajan PS, Rangarajan M, Prasad M, Kalyanakumari V, Parthasarathi R, et al. NOTES: transvaginal endoscopic cholecystectomy in humans-preliminary report of a case series. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009. 104:843–847.

25. Leroy J, Cahill RA, Asakuma M, Dallemagne B, Marescaux J. Single-access laparoscopic sigmoidectomy as definitive surgical management of prior diverticulitis in a human patient. Arch Surg. 2009. 144:173–179.

26. Kang KC, Lee SY, Kang DB, Kim SH, Oh JT, Choi DH, et al. Application of single incision laparoscopic surgery for appendectomies in patients with complicated appendicitis. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2010. 26:388–394.

27. Lee JS, Hong TH, Kim JG. A comparison of the periumbilical incision and the intraumbilical incision in laparoscopic appendectomy. J Korean Surg Soc. 2012. 83:360–366.

28. Kim HO, Yoo CH, Lee SR, Son BH, Park YL, Shin JH, et al. Pain after laparoscopic appendectomy: a comparison of transumbilical single-port and conventional laparoscopic surgery. J Korean Surg Soc. 2012. 82:172–178.

29. Park JH, Hyun KH, Park CH, Choi SY, Choi WH, Kim DJ, et al. Laparoscopic vs transumbilical single-port laparoscopic appendectomy; results of prospective randomized trial. J Korean Surg Soc. 2010. 78:213–218.

30. Lee YS, Kim JH, Moon EJ, Kim JJ, Lee KH, Oh SJ, et al. Comparative study on surgical outcomes and operative costs of tran sumbilical single-port laparoscopic appendectomy versus conventional laparoscopic appendectomy in adult patients. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009. 19:493–496.

ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download