Abstract

Subclavian venous catheterization was once widely used for volume resuscitation, emergency venous access, chemotherapy, parenteral nutrition, and hemodialysis. However, its use has drastically reduced recently because of life-threatening complications such as hemothorax, pneumothorax. In this case, a patient admitted for a scheduled operation underwent right subclavian venous catheterization for preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative volume resuscitation and parenteral nutrition. The procedure was performed by an experienced senior resident. Despite detecting slight resistance during the guidewire insertion, the resident continued the procedure to the point of being unable to advance or remove it, then attempted to forcefully remove the guidewire, but it broke and became entrapped within the thorax. We tried to remove the guidewire through infraclavicular skin incision but failed. So video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery was used to remove the broken guidewire. This incident demonstrates the risks of subclavian venous catheterization and the importance of using a proper and gentle technique.

Central vein catheterization has commonly been used for volume resuscitation, emergency venous access, chemotherapy, parenteral nutrition, hemodialysis, and central venous pressure monitoring. The percutaneous approach includes access via the internal jugular vein, femoral vein, or subclavian vein. During a case of right subclavian venous catheterization using the landmark method, we experienced extravasation, breakage, and entrapment of a guidewire within the thorax that was subsequently removed using video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). We report this case for educational purposes because this procedure is common but must be performed carefully.

A 79-year-old female patient diagnosed with ascending colon cancer was admitted to the Division of Colon and Rectal Surgery of our institution for a scheduled operation on July 23, 2012. At admission, the patient's calculated Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score was 10 with a predicted death rate of 11.3%. Central venous catheterization was performed for preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative volume resuscitation and nutritional therapy. A senior surgical resident used the landmark method to perform catheterization of the right subclavian vein. The Spectrum Central Venous Catheter Set (length, 20 cm; size, 7.0 F; William A. Cook Australia Pty. Ltd., Brisbane, Australia) was used (Fig. 1). The included guidewire had a J-tip (Fig. 2).

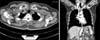

The right subclavian vein was successfully punctured using the Seldinger technique, and the guidewire was then inserted. The patient was not obese, and her anatomic landmarks were clear. Slight resistance was detected during the guidewire insertion process, but the resident proceeded with it. When guidewire advancement was not possible, its removal was attempted. However, by this point, it could be neither advanced nor removed because of resistance. Forced removal was attempted but resulted in guidewire breakage and entrapment. Its location could not be determined by palpation. Chest radiography was immediately performed to determine the position of the guidewire, and the results indicated guidewire looping and entrapment within the upper right clavicle (Fig. 3). Chest computed tomography scans revealed that the broken guidewire was outside the vein and had not induced hemothorax, pneumothorax, or hematoma of the soft tissues (Fig. 4). After we had explained this to the patient, under local anesthesia, we tried to remove the broken guidewire through infraclavicular skin incision but we could not find the guidewire.

The patient was transferred to the operating room for the scheduled operation and underwent VATS of the right thorax. The operation took 120 minutes. The surgical manifestation was metallic foreign body impaction in the upper chest wall that was successfully removed (Fig. 5). The patient was discharged 14 days after the scheduled right colectomy without significant complications. Volume resuscitation was conducted through the internal jugular vein during the operation, while nutritional support was delivered via peripheral venous access.

The use of subclavian venous access has decreased in recent years because of its associated potentially life-threatening complications such as hemothorax, pneumothorax, and mediastinal hematoma. However, it has the advantages of increased patient comfort and convenience in the postoperative care period [1]. Especially considering its convenience of consistent landmarks despite being a blind procedure in emergent settings, it is frequently performed when rapid venous access is required, such as during cardiopulmonary resuscitation [2].

A recent study reported that the use of bedside real-time ultrasound for subclavian vein catheterization was effective. However, more studies have demonstrated that the ultrasound technique is better than the landmark method in the internal jugular vein, and its effectiveness in the subclavian vein is both controversial and known to be technically difficult [3-5]. When ultrasound is not possible or a patient is in a surgically emergent setting, rapid venous access via the subclavian Fig. 5. (A) Entrapped guide wire visualized on thoracoscopy. (B) Completely removed guide wire. Fig. 4. Chest computed tomographic scan showed entrapped guide wire located outside the vein. vein is still frequently performed. Wang and Sweeney [6] reported a case of guidewire entrapment during left subclavian venous catheterization in which they were able to remove the entrapped catheter using gentle traction. That report argued that a guidewire should not be inserted further if resistance is detected during insertion or removal, and that J-tip guidewires should be used to reduce the risk of vascular perforation [6]. Despite these lessons of Wang and Sweeney [6], complications involving guidewire knotting and entrapment have occasionally been reported. Onan et al. [7] recently reported a case of a knotted and entrapped guidewire that was removed using an infraclavicular incision under local anesthesia. In our case, because the patient was already scheduled for an operation that required general anesthesia, the entrapped guidewire can be removed using VATS.

There has been a recent decrease in the use of the subclavian venous catheterization method. However, use of this procedure is inevitable sometimes in emergency conditions requiring rapid venous access or when other insertion sites are unavailable because of previous insertions or catheter-related infections. Therefore, surgeons and physicians must be well familiarized with and educated on the standard landmark method. As our experience demonstrates, resistance encountered during guidewire insertion indicates possible knotting, looping, or entrapment; in such cases, the guidewire should not be forcibly inserted or removed. We thought that the guidewire was likely sheared by the needle. In addition, when experts are not available, the use of ultrasound-guided internal jugular vein access rather than the subclavian vein approach can help reduce the risk of complications.

In conclusion, mastery of the basic principles of this technique is important, and such procedures should be gently performed using accurate landmark assessment with the patient in Trendelenburg position long enough to allow for sufficient venous retention.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1The Spectrum Central Venous Catheter Set (length, 20 cm; size, 7.0 F; William A. Cook Australia Pty. Ltd.). |

References

1. De Moor B, Vanholder R, Ringoir S. Subclavian vein hemodialysis catheters: advantages and disadvantages. Artif Organs. 1994; 18:293–297.

2. Emerman CL, Bellon EM, Lukens TW, May TE, Effron D. A prospective study of femoral versus subclavian vein catheterization during cardiac arrest. Ann Emerg Med. 1990; 19:26–30.

3. Fragou M, Gravvanis A, Dimitriou V, Papalois A, Kouraklis G, Karabinis A, et al. Real-time ultrasound-guided subclavian vein cannulation versus the landmark method in critical care patients: a prospective randomized study. Crit Care Med. 2011; 39:1607–1612.

4. Mansfield PF, Hohn DC, Fornage BD, Gregurich MA, Ota DM. Complications and failures of subclavian-vein catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1994; 331:1735–1738.

5. Slama M, Novara A, Safavian A, Ossart M, Safar M, Fagon JY. Improvement of internal jugular vein cannulation using an ultrasound-guided technique. Intensive Care Med. 1997; 23:916–919.

6. Wang HE, Sweeney TA. Subclavian central venous catheterization complicated by guidewire looping and entrapment. J Emerg Med. 1999; 17:721–724.

7. Onan B, Oz K, Onan IS. Knotted Seldinger guidewire as a complication of Hickman catheter implantation. J Vasc Access. 2010; 11:171–172.

ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download