Abstract

Purpose

It is increasingly being recognized that the lymph node ratio (LNR) is an important prognostic factor for gallbladder carcinoma patients. The present study evaluated predictors of tumor recurrence and survival in a large, mono-institutional cohort of patients who underwent surgical resection for gallbladder carcinoma, focusing specifically on the prognostic value of lymph node (LN) status and of LNR in stage IIIB patients.

Methods

Between 2004 and 2011, 123 patients who underwent R0 radical resection for gallbladder carcinoma at the Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital were reviewed retrospectively. Patients were staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th edition, and prognostic factors affecting disease free survival, such as age, sex, comorbidity, body mass index, presence of preoperative symptoms, perioperative blood transfusion, postoperative complications, LN dissection, tumor size, differentiation, lymph-vascular invasion, perineural invasion, T stage, presence of LN involvement, N stage, numbers of positive LNs, LNR and implementation of adjuvant chemotherapy, were statistically analyzed.

Results

LN status was an important prognostic factor in patients undergoing curative resection for gallbladder carcinoma. The total number of LNs examined was implicated with prognosis, especially in N0 patients. LNR was a powerful predictor of disease free survival even after controlling for competing risk factors, in curative resected gallbladder cancer patients, and especially in stage IIIB patients.

Adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder has historically been considered an incurable malignancy with dismal prognosis due to its propensity for early dissemination. Complete surgical resection with tumor-free surgical margins, especially in the early stages of the disease, offers the only hope for long-term survival and is considered a standard of care. Thus, accurate identification of the extent of disease is an important diagnostic consideration for therapeutic decision-making of gallbladder cancer.

The presence or absence of lymph node (LN) metastases is an established prognostic factor in patients with resected gallbladder carcinoma [1-3]. Patients with LN metastases have a significantly worse survival than patients with node-negative disease [4]. Most Eastern surgeons and even some Western surgeons have adopted radical LN dissection for this disease and have reported the beneficial effect of nodal dissection on survival and some long-term survivors with nodal disease [5-10]. Thus, it appears that radical LN dissection plays a critical role in the surgical management of gallbladder cancer.

Increasingly, the idea that an inadequate number of LNs examined may adversely influence on survival and lead to understaging of various gastrointestinal cancers is being recognized [11]. Rather, evidence in the literature that is based on other malignancies demonstrates that the actual number of LNs evaluated had an effect on survival [12-14]. In fact, most studies have demonstrated an inverse relationship between the number of LNs examined and overall survival. Moreover, the ratio between metastatic and examined LNs is an additional recent prognostic factor in different gastrointestinal malignancies [15-17]. Le Voyer et al. [14] analyzed data from patients with stage II and III colon cancer, and reported that the lymph node ratio (LNR) was an important prognostic factor even after adjusting for other parameters such as tumor stage, grade, and histology. Marchet et al. [18] and Pawlik et al. [19] also demonstrated that LNR was an independent predictor of survival in gastric cancer and pancreas cancer, respectively.

In the light of these considerations, the aim of the present study was to evaluate predictors of tumor recurrence and survival in a large, mono-institutional cohort of patients who underwent surgical resection for gallbladder carcinoma, focusing specifically on the prognostic value of LN status and of LNR in stage IIIB patients.

Between 2004 and 2011, retrospective data was collected from 144 consecutive patients with gallbladder carcinoma who underwent laparotomy at Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital. Fifteen patients who underwent palliative surgery or a resection with microscopic or macroscopic residual tumor were excluded, as were six patients who underwent exploratory laparotomy because of peritoneal seeding (Fig. 1). The remaining 123 patients who underwent a R0 radical resection for gallbladder carcinoma were included. Demographics, operative details, and pathologic details of the 123 patients were recorded.

The operative procedure basically consisted of cholecystectomy, regional lymphadenectomy, and resection of the gallbladder bed with a rim of the adjacent liver tissue. Cholecystectomy included the removal of the entire connective tissue lying between the gallbladder and the liver parenchyma. Lymphadenectomy included en bloc clearance of cystic duct, pericholedochal, hepatic artery, portal vein LNs, and, if needed, periduodenal, peripancreatic, celiac, and aortocaval LNs. Wedge resection involved a 2-cm deep nonanatomical wedge resection of gallbladder fossa, with the guiding principle being attainment of negative surgical margin while at the same time preserving the maximal amount of liver parenchyma. In all the patients, frozen section analysis of cystic duct remnant was obtained to ensure negative margin. Bile duct resection was not performed routinely, except in case of positive cystic duct margin or definite bile duct invasion.

The choice of a radical resection procedure for each patient depended on the extent of the tumor on preoperative cross sectional imaging. Some early-stage diseases required less aggressive resection. Five patients with pathologically proven T1a (confined within the lamina propria of the primary tumor) after laparoscopic cholecystectomy did not have an additional procedure. Although the tumor extent of T1b with relaparotomy after laparoscopic cholecystectomy is debatable, we did not perform more procedures in seven patients proven as T1b after cholecystectomy. Twelve patients underwent major hepatectomy depending on the extent of the tumor and two patients received additional pancreatico-duodenectomy: one because of an extension of the tumor to the intrapancreatic bile duct and the other due to involvement of peripancreatic LNs. Another two patients also received an additional pancreatico-duodenectomy without major hepatectomy for similar reasons. Adjacent organs, such as colon and stomach, were resected in nine patients owing to direct invasion in the operative field (Table 1).

Primary tumor was examined to determine the size of the primary tumor, histologic type, histologic grade, depth of infiltration, lympho-vascular invasion, perineural invasion, and tumor involvement of excised contiguous viscera and resection margins. Although the pathologic findings were staged using the 6th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) manual during the period of study, final description was done according to the 7th edition of the AJCC classification. The primary tumor status was pT1a in 11 patients, pT1b in 15, pT2 in 69, pT3 in 25, and pT4 in 2.

The histologic grade was determined based on the area of tumor with highest grade and was classified as well differentiated or not well differentiated (moderate or poor). Adenocarcinoma was identified in 102 patients of primary gallbladder tumor, papillary adenocarcinoma in nine patients, adenosquamous carcinoma in five patients, carcinosarcoma in three patients, undifferentiated carcinoma in two patients, and combined adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma in two patients.

Fibrofatty tissue containing LNs were retrieved from the specimen just after resection, and nodes were meticulously separated into individual node groups according to the location of the LNs. LN metastasis was defined as tumor cells detected on histopathologic examination using hematoxylin and eosin stain. The location and the number of positive LNs were used to assess the degree of lymphatic spread. The location of positive LN was classified into three categories according to the 7th edition of AJCC classification: pathologic N0 (pN0), no regional LN metastasis; pathologic N1 (pN1), metastases to nodes along the cystic duct, common bile duct, hepatic artery, and/or portal vein; pathologic N2 (pN2), metastases to periaortic, pericaval, superior mesenteric artery, and/or celiac artery LNs. The number of total retrieved LNs and positive LNs were recorded for each patient. LNR was determined by dividing the total number of LNs harboring metastases by the total number of examined nodes. Patients were divided into three different groups based on their LNR, including one group of patients with negative nodes (LNR = 0) and two groups with positive LNs as follows, based on sensitivity analyses that identified this cutoff value as potentially being the most discriminating: 0 < LNR ≤ 0.5, and LNR more than 0.5.

Follow-up comprised physical examination, laboratory tests including tumor markers (carcinoembryonic antigen, cancer antigen 19-9), and imaging study including abdominal ultrasonography and computed tomography. Follow-up was carried out every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months thereafter. Follow-up tests were performed any time if there was suspicion of disease recurrence.

Adjuvant chemotherapy after resection was administered at the discretion of the individual surgeons, though most patients with positive LNs were recommended. Forty four patients received adjuvant chemotherapy with intravenous gemcitabine intend to receive 6 cycles. No patient received adjuvant radiotherapy.

The sites of recurrence were recorded only when a lesion was visible at imaging and was classified as loco-regional (liver resection margin, hepaticojejunostomy, or regional LNs), distant (liver, peritoneum, or systemic), or both. Disease-free survival (DFS) was calculated from the day of surgery to the time when recurrent disease was first detected. Death of patients was defined as disease related or due to other causes, in order to evaluate disease specific survival.

Medical records and survival data were obtained for all 123 patients. Continuous data are presented as median (interquartile range). Categorical variables were compared using chi square or Fisher's test. When comparing two groups, normally distributed continuous variables were compared using a two-sample Student's t-test, while the Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed variables. Survival was defined as the time from diagnosis to death. The primary outcome parameter of interest was DFS and is expressed as median ± standard error. Survival probability was estimated according to the Kaplan-Meier method, whereas the log-rank test was used for univariable comparison between groups. A Cox proportional hazards regression model using a step-backward fitting procedure was applied to determine significant influence on survival. Risk factors associated with disease recurrence were determined by multivariate logistic regression. The hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was reported as an estimate of the risk of disease specific death. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed with the PASW ver. 18.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

At a median follow-up of 22.8 months (range, 3.1 to 100.7 months), the overall cumulative DFS rates of the 123 patients who underwent radical procedure for gallbladder carcinoma were 65% at 3 years and 63% at 5 years. The overall cumulative survival rates were 67% at 3 years and 60% at 5 years. There was no perioperative mortality. The median DFS time and overall survival time were 16.4 months and 22.8 months respectively.

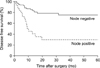

Sixty six patients (67%) were node negative patients and positive LNs were found in 33 patients (33%) among the 99 patients who underwent LN harvest. Twenty six patients were included in the pN1 group and seven patients were in pN2 group with positive celiac and paraaortic nodal disease. Patients with node negative disease had a median survival of 22.7 months compared with a median survival of 7.3 months for patients with positive LNs (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The number of dissected regional LNs was extremely high in patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy or stomach resection. The mean number of harvested and positive regional LNs was 5.31 and 0.73, respectively.

On univariate analysis, factors associated with worse DFS included nonwell differentiated histologic group, presence of lymph-vascular invasion, presence of perineural invasion, T-stage more than T3, LN involvement, higher N stage, and higher LN ratio (Table 2). The significant univariate variables were entered into Cox regression multivariate analysis; high T-stage group and LN ratio remained as independently significant variables. Patients in the T3-T4 group had a median survival of 6.97 months compared with a median survival of 21.4 months for patients in the T1-T2 group. The T3-T4 patients had a nearly 3-fold increased risk of recurrence (HR, 2.998; 95% CI, 1.392 to 6.458; P = 0.005) compared with patients in the T1-T2 group. LNR was also associated strongly with prognosis. Patients with a LNR exceeding 0.5 had an almost 5-fold increased risk of recurrence rate (HR, 5.998; 95% CI, 2.576 to 13.962; P < 0.001) compared with patients who had a LNR of 0 (Table 3).

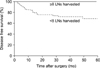

Patients without metastasis to adjacent LNs (n = 66) had a 5-year DFS of 77.8%. Univariate analysis of risk factors for tumor recurrence revealed T3-T4 tumor stage, poor tumor differentiation, lymphovascuar invasion, and perineural invasion as significantly associated with tumor recurrence. On multivariate analysis, T3-T4 tumor stage was significantly associated with poor disease free survival (HR, 7.654; 95% CI, 2.014 to 29.085; P = 0.003). Tumor grade worse than well differentiation had statistical significance (HR, 4.550; 95% CI, 1.085 to 19.091; P = 0.038) (Table 4). Total number of harvested LNs was not associated with DFS. Patients with N0 disease were stratified in two groups according to the total number of LNs evaluated. Because eight LNs tended to determine the greatest actuarial survival difference between the resulting groups, we used this value as the cutoff. N0 patients who had at least eight LNs evaluated had superior DFS than patient with fewer number of LNs examined, but the difference was not significant (P = 0.087) (Fig. 3).

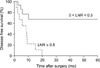

All N1 gallbladder cancer patients with T1-T3 tumor depth were classified as stage IIIB in the AJCC 7th edition. According to the classification, T4 and N2 were included in stage IV disease meaning poor prognosis like distant metastasis. Thus, in this study, we analyzed prognostic factors of stage IIIB patients, akin to the analysis of node positive patients in other studies. Age, sex, comorbidity, body mass index (BMI), presence of preoperative symptom, perioperative blood transfusion, postoperative complication, tumor size, differentiation, lymph-vascular invasion, perineural invasion, T stage, numbers of positive LNs, LNR, and implementation of adjuvant chemotherapy were identified as prognostic factors that influenced DFS. In univariate analysis, presence of comorbidity and LNR ≥0.5 were associated with significantly worse DFS in stage IIIB gallbladder cancer patients after curative resection. However, subsequent multivariate analysis revealed only LNR ≥0.5 to be an independent predictor of DFS in those patients (HR, 5.231; 95% CI, 1.586 to 17.255; P = 0.007) (Table 5, Fig. 4).

Complete surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment in patients with localized gallbladder cancer. In patients with early gallbladder carcinoma, in which invasion was limited to the muscularis propria layer, favorable outcome has been achieved [20-22]. Although, there has been little controversy concerning the operative strategy of early gallbladder carcinoma limited to the lamina propria layer (T1a), but there are still many debates about the operative methods in gallbladder carcinoma limited to the muscularis propria (T1b). Since Glenn and Hays [23] proposed 'radical cholecystectomy' for gallbladder carcinoma involving the en bloc excision of the gallbladder bed with a rim of the adjacent liver tissue and the lymphatic tissue within hepatoduodenal ligament in 1954 [1], a favorable outcome has been achieved for advanced gallbladder cancer. Also extended resection including extended LN dissection, extended hepatectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, and combined vascular resection has been performed in far advanced gallbladder carcinoma [24,25]. Although mortality and mobidity rates have been high, many surgeons have reported a number of long-term survivors [5-9,24]. This suggests that extended resection is effective for select cases of advanced gallbladder carcinoma.

At diagnosis, accurate and uniform gallbladder cancer staging is essential for prognosis, planning treatment, and comparing treatment outcomes. Currently, gallbladder cancer is staged by two main staging systems: the AJCC tumor-node-metastasis staging system (7th edition) [2] and the Japanese Society of Biliary Surgery (JSBS) staging system [3]. In the AJCC 7th edition, the nodal status has been divided into three groups based on the presence of positive LNs and the anatomic location of positive LNs: N0 (no regional LN metastasis), N1 (metastases to nodes along the cystic duct, common bile duct, hepatic artery, and/or portal vein), and N2 (metastases to periaortic, pericaval, superior mesenteric artery, and/or celiac artery LNs). The JSBS subdivides the nodal status of gallbladder carcinoma into four categories, according to the anatomic location of positive LNs: N0, N1, N2, or N3. We adopted the AJCC staging system because it is the most accepted system worldwide, and also JSBS requires extended LN dissection to acquire sufficient knowledge on the LN status.

The present study revealed that the survival rates of patients with node positive gallbladder carcinoma are worse than those of node negative, although LN metastasis itself had insignificant prognostic power in multivariate analysis. LN metastasis is consistently one of the strongest predictors of poor outcome in patients with advanced gallbladder carcinoma [4,26-28]. Few Western reports have described long-term, disease-free survivor who had lymphatic metastases [26]. In contrast, Japanese reports showed that the prognosis of patients who had LN metastasis limited to the LN within the hepatoduodenal ligament is improved by LN dissection [5,27]. In our study, 5-year survival of node negative patients was 80.3%, whereas that of node positive patients was 48.5% (P < 0.001). Among the node positive patients, the N2 group belongs to stage IVB according to the AJCC 7th edition, and has little chance of long-term survival. Whereas patients in N1 group, especially in stage IIIB with T1-T3, are expected to survive for a relatively long time, so it is important to select long-term survivors among the patients with stage IIIB, and to analyze the prognostic factors.

Recent studies have also demonstrated the influence of retrieved LN counts, metastatic LN counts, and LNR on survival of patients with gallbladder carcinoma [29,30]. Presently, the survival of N0 patients who had fewer than eight LNs evaluated at the time of operation tended to be shorter than the survival of N0 patients who had at least eight LNs examined (Fig. 3). Negi et al. [29] also reported that N0 patients with fewer than six LNs had worse prognosis. The total number of LNs examined in presumed N0 patients, therefore, appears to be an important prognostic variable. Specifically, N0 patients who have fewer than six to eight LNs examined may be understaged due to an inadequate LN evaluation. Despite the lack of statistical significance in the current study, the strong trend was seen in both the current study and the study by Negi et al. [29], as well as the established biologic plausibility of this concept based on other disease sites.

In contrast to N0 patients, in N1 patients, the total number of LNs evaluated was not an important prognostic variable. The presence of LN metastases was such a strong prognostic factor that it probably outweighed any prognostic effect of the total number of LNs evaluated.

Using the presence of nodal disease or absolute number of affected LNs may introduce bias due to the inevitable possibility of incomplete lymphadenectomy or inadequate histopathologic examination. To overcome the potential problems associated with nodal staging and to define better the prognostic role of nodal disease, several studies have used the LNR as a prognostic parameter for various gastrointestinal tumors. LNR, rather than total node count or total number of positive LNs, may have benefit for a number of different reasons. Firstly, LNR provides a denominator that accounts for some degree of adequacy of the LN dissection. Consequently, LNR is less prone to "stage migration." Bando et al. [12] and Inoue et al. [13] also have demonstrated the superiority of LNR for gastric cancer as compared to routine staging of LNs with regard to stage migration. Secondly, LNR provides for a more clinically distinct comparison of patients with similar counts of total positive LNs. For example, patients with two positive LNs, but different numbers of retrieved LNs (4 and 40) have different LNR (0.5 and 0.05). Comparison between the patients with positive LN counts may not be appropriate. Thus, LNR provides a more discriminatory tool to stratify patients based on both the extent of their disease as well as the adequacy of their lymphadenectomy.

As our data demonstrated, LNR and T-stage affect DFS in patients with radically resected gallbladder carcinoma; in particular, a LNR exceeding 0.5 had the highest HR. In N1 patients, especially in stage IIIB patients of gallbladder carcinoma, LNR was the most potent predictor of prognosis when we adjusted for many competing risk factors, such as age, sex, comorbidity, BMI, presence of preoperative symptoms, perioperative blood transfusion, postoperative complications, tumor size, differentiation, lymph-vascular invasion, perineural invasion, T stage, numbers of positive LNs, and implementation of adjuvant chemotherapy. Thus, LNR was confirmed as an independent prognostic factor in N1 patients, especially in stage IIIB gallbladder carcinoma.

In conclusion, LN status is an important prognostic factor in patients undergoing curative resection for gallbladder carcinoma. The total number of LNs examined may be associated with prognosis, especially in N0 patients. In patients with stage IIIB disease, a high LNR appears to be a better prognostic predictor than simply the total number of positive LNs. LNR remained a powerful predictor of DFS even after controlling for competing risk factors, in curative resected gallbladder cancer patients, and especially in stage IIIB patients. LNR should be considered as a prognostic factor and stratification tool in future trials evaluating adjuvant treatments in radically resected gallbladder carcinoma patients.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 2Kaplan-Meier survival curves according to the presence or absence of regional nodal disease. Five-year disease free survival rate was 80.3% in patients without regional nodal disease, but the median survival time was not reached. The five-year disease free survival rate was 48.5% with a median survival time of 30 months in patients with regional nodal disease (P < 0.001). |

| Fig. 3Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing patients in node negative disease with fewer than eight lymph nodes (LNs) examined to those with eight or more LNs examined. All the patients with more than eight LNs examined were not recurred, whereas patients with fewer than eight LNs examined displayed 5-year disease free survival rate of 73.7% (P = 0.087). |

| Fig. 4Kaplan-Meier survival curves according to the lymph node ratio in patients with stage IIIB gallbladder cancer. Five-year disease free survival rate was 75% in patients with a lymph node ratio (LNR) < 0.5, but the median survival time was not reached. The 5-year disease free survival rate was only 10% with a median survival time of 8.5 months in patients with a LNR > 0.5 (P = 0.003). |

Table 2

Univariate analysis of factors associated with disease-free survival after curative intent resection for gallbladder cancer

Table 3

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with disease

free survival after curative intent resection for gallbladder cancer

References

1. Shirai Y, Wakai T, Hatakeyama K. Radical lymph node dissection for gallbladder cancer: indications and limitations. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2007. 16:221–232.

2. Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC cancer staging manual. 2010. 7th ed. New York: Springer.

3. Japanese Society of Biliary Surgery. Classification of biliary tract carcinoma. 2004. 2nd ed. Tokyo: Kanehara.

4. Benoist S, Panis Y, Fagniez PL. French University Association for Surgical Research. Long-term results after curative resection for carcinoma of the gallbladder. Am J Surg. 1998. 175:118–122.

5. Tsukada K, Kurosaki I, Uchida K, Shirai Y, Oohashi Y, Yokoyama N, et al. Lymph node spread from carcinoma of the gallbladder. Cancer. 1997. 80:661–667.

6. Kondo S, Nimura Y, Hayakawa N, Kamiya J, Nagino M, Uesaka K. Regional and para-aortic lymphadenectomy in radical surgery for advanced gallbladder carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2000. 87:418–422.

7. Endo I, Shimada H, Tanabe M, Fujii Y, Takeda K, Morioka D, et al. Prognostic significance of the number of positive lymph nodes in gallbladder cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006. 10:999–1007.

8. Sasaki R, Itabashi H, Fujita T, Takeda Y, Hoshikawa K, Takahashi M, et al. Significance of extensive surgery including resection of the pancreas head for the treatment of gallbladder cancer: from the perspective of mode of lymph node involvement and surgical outcome. World J Surg. 2006. 30:36–42.

9. Yokomizo H, Yamane T, Hirata T, Hifumi M, Kawaguchi T, Fukuda S. Surgical treatment of pT2 gallbladder carcinoma: a reevaluation of the therapeutic effect of hepatectomy and extrahepatic bile duct resection based on the long-term outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007. 14:1366–1373.

10. D'Angelica M, Dalal KM, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR. Analysis of the extent of resection for adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009. 16:806–816.

11. Smith DD, Schwarz RR, Schwarz RE. Impact of total lymph node count on staging and survival after gastrectomy for gastric cancer: data from a large US-population database. J Clin Oncol. 2005. 23:7114–7124.

12. Bando E, Yonemura Y, Taniguchi K, Fushida S, Fujimura T, Miwa K. Outcome of ratio of lymph node metastasis in gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002. 9:775–784.

13. Inoue K, Nakane Y, Iiyama H, Sato M, Kanbara T, Nakai K, et al. The superiority of ratio-based lymph node staging in gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002. 9:27–34.

14. Le Voyer TE, Sigurdson ER, Hanlon AL, Mayer RJ, Macdonald JS, Catalano PJ, et al. Colon cancer survival is associated with increasing number of lymph nodes analyzed: a secondary survey of intergroup trial INT-0089. J Clin Oncol. 2003. 21:2912–2919.

15. Nitti D, Marchet A, Olivieri M, Ambrosi A, Mencarelli R, Belluco C, et al. Ratio between metastatic and examined lymph nodes is an independent prognostic factor after D2 resection for gastric cancer: analysis of a large European monoinstitutional experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003. 10:1077–1085.

16. Berger AC, Sigurdson ER, LeVoyer T, Hanlon A, Mayer RJ, Macdonald JS, et al. Colon cancer survival is associated with decreasing ratio of metastatic to examined lymph nodes. J Clin Oncol. 2005. 23:8706–8712.

17. Mariette C, Piessen G, Briez N, Triboulet JP. The number of metastatic lymph nodes and the ratio between metastatic and examined lymph nodes are independent prognostic factors in esophageal cancer regardless of neoadjuvant chemoradiation or lymphadenectomy extent. Ann Surg. 2008. 247:365–371.

18. Marchet A, Mocellin S, Ambrosi A, Morgagni P, Garcea D, Marrelli D, et al. The ratio between metastatic and examined lymph nodes (N ratio) is an independent prognostic factor in gastric cancer regardless of the type of lymphadenectomy: results from an Italian multicentric study in 1853 patients. Ann Surg. 2007. 245:543–552.

19. Pawlik TM, Gleisner AL, Cameron JL, Winter JM, Assumpcao L, Lillemoe KD, et al. Prognostic relevance of lymph node ratio following pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2007. 141:610–618.

20. Shimada H, Endo I, Togo S, Nakano A, Izumi T, Nakagawara G. The role of lymph node dissection in the treatment of gallbladder carcinoma. Cancer. 1997. 79:892–899.

21. Yamaguchi K, Chijiiwa K, Saiki S, Nishihara K, Takashima M, Kawakami K, et al. Retrospective analysis of 70 operations for gallbladder carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1997. 84:200–204.

22. Miyakawa S, Ishihara S, Horiguchi A, Takada T, Miyazaki M, Nagakawa T. Biliary tract cancer treatment: 5,584 results from the Biliary Tract Cancer Statistics Registry from 1998 to 2004 in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009. 16:1–7.

23. Glenn F, Hays DM. The scope of radical surgery in the treatment of malignant tumors of the extrahepatic biliary tract. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1954. 99:529–541.

24. Miyazaki M, Itoh H, Ambiru S, Shimizu H, Togawa A, Gohchi E, et al. Radical surgery for advanced gallbladder carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1996. 83:478–481.

25. Kondo S, Nimura Y, Hayakawa N, Kamiya J, Nagino M, Uesaka K. Extensive surgery for carcinoma of the gallbladder. Br J Surg. 2002. 89:179–184.

26. Fong Y, Wagman L, Gonen M, Crawford J, Reed W, Swanson R, et al. Evidence-based gallbladder cancer staging: changing cancer staging by analysis of data from the National Cancer Database. Ann Surg. 2006. 243:767–771.

27. Kondo S, Takada T, Miyazaki M, Miyakawa S, Tsukada K, Nagino M, et al. Guidelines for the management of biliary tract and ampullary carcinomas: surgical treatment. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008. 15:41–54.

28. Jensen EH, Abraham A, Jarosek S, Habermann EB, Al-Refaie WB, Vickers SA, et al. Lymph node evaluation is associated with improved survival after surgery for early stage gallbladder cancer. Surgery. 2009. 146:706–711.

29. Negi SS, Singh A, Chaudhary A. Lymph nodal involvement as prognostic factor in gallbladder cancer: location, count or ratio? J Gastrointest Surg. 2011. 15:1017–1025.

30. Shirai Y, Sakata J, Wakai T, Ohashi T, Ajioka Y, Hatakeyama K. Assessment of lymph node status in gallbladder cancer: location, number, or ratio of positive nodes. World J Surg Oncol. 2012. 10:87.

ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download