Abstract

Extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma is rare and presents variable symptoms. Its difficulty to diagnosis delays appropriate treatment. We would like to report an unusual case of extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma. The patient came to the emergency room with dyspnea, palpitation, and cyanosis. He had a history of hospitalization for Fontan operation due to congenital heart disease. Despite medication, his blood pressure remained high. After additional laboratory and image exams, he was diagnosed with extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma and had surgical treatment. The final pathology report was extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma with high risk of malignancy. The postoperative course was uneventful and showed normal laboratory results even after 3 months of outpatient follow-up. Extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma presents variable symptoms. We should consider endocrinologic diseases like extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma in cases presenting with palpitation and high blood pressure, even with a past history of cardiac surgery.

The incidence of congenital heart disease has been gradual increasing, may be due to increase of prenatal detection by fetal echocardiography [1]. Most patients with congenital heart disease require an operation and suffer from postoperative complications including dysrhythmias, myocardial infarct, and heart failure. In patients with postoperative hemodynamic symptoms who present at the hospital, heart problem is the first diagnosis of consideration. But other causes should be considered. The present case describes an 18-year-old boy with dyspnea, palpitation, and cyanosis who underwent a Fontan operation due to congenital heart disease.

An 18-year-old boy presented at the emergency room (ER) with dyspnea and palpitation. The patient, born at 40 weeks of gestation, had been diagnosed with a complex congenital heart disease (single ventricle, complete endocardial cushion defect, secundum atrial septal defect, complete transposition of the great arteries with pulmonary stenosis, dextrocardia, bilateral superior vena cava, supracardial type total anomalous pulmonary venous return, and separate hepatic vein) at 2 months of age. The patient underwent a total anomalous pulmonary venous return correction at the age of 1, and modified Fontan operation at age 3. After the operation, the patient was checked three times by cardiac angiography for dyspnea. The patient was on aspirin (100 mg twice a day), digoxin (0.25 mg), enalapril (5 mg), and atenolol (12.5 mg once a day).

The patient came to the ER for treatment of dyspnea, palpitation, and mild cyanosis. While in the ER, heart rate and blood pressure were elevated to 190 beats per minute and 141/81 mmHg, respectively. The patient showed no response to adenosine. However, the patient went into cardiogenic shock during verapamil infusion, with unmeasurable blood pressure. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit, and after one day of inotropics treatment, blood pressure began to recover, and the patient was weaned from the drugs. The attending pediatric cardiologist restarted enalapril (2.5 mg twice a day) because of rising blood pressure, and consecutively added digoxin (0.25 mg once a day), carvedilol (3.125 mg), and sotalol (80 mg twice a day). Despite medication, the elevated blood pressure continued.

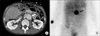

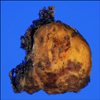

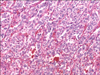

Catecholamine and 24-hour urine vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) levels were measured in order to rule out pheochromocytoma. Test results revealed elevated norepinephrine (4,422 pg/mL) and urine VMA (11.4 mg/day). Epinephrine and dopamine were within normal ranges. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) and metaiodobenzylguanidine test were performed, which confirmed the presence of a 3 × 4 cm well-defined, enhancing left para-aortic mass (Fig. 1) with highly suggestive of pheochromocytoma. The mass was suspected to be an extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma, and was surgically removed. The mass was firmly adhered to surrounding tissues, including the aorta, requiring meticulous excision. Grossly, the mass showed round, firm and brownish feature. The permanent pathology reported the tumor as an extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma, with a high risk of malignancy (Fig. 2). Microscopically, the arrangement of large cells (Zellballen) and slightly basophilic cytoplasm with neuroendocrine granules were evident (Fig. 3). The immunohistochemistry test for this tumor was performed, which showed positive for CD56, synaptophysin, chromogranin, Ki-67 and S-100. It was consistent with pheochromocytoma.

The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient's vital signs have remained stable and normal range laboratory findings evident after 3 months of clinical follow-up.

Pheochromocytoma and extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma developed from neural crest cells and produce catecholamine, including dopamine, norepinephrine and epinephrine [2]. Extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma, also called paraganglioma, involves 0.2% of hypertensive patients [3]. The symptoms of extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma are variable and can constitute a classic triad of headache, diaphoresis, and palpitation [3]. Other minor symptoms include hemoptysis, dypsnea, abdominal pain, and constipation [4]. The symptoms, however, are correlated with tumor site. Park et al. [5] reported 33-year old woman with neck swelling who diagnosed carotid body paraganglioma.

Differential diagnosis of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma is important for surgeon. Misdiagnosis of that tumor might be cause confusion during surgery for appropriate extent of excision. Paraganglioma arises in various parts of the body as carotid body, sellar region of brain and so on [5,6]. Paraganglioma is often mistakenly considered for another disease such as parathyroid adenoma, pituitary microadenoma [6,7].

The prevalence of congenital heart disease prevalence is about 11 to 13 per 1,000 children and the main symptoms are cyanosis and dyspnea [1,8]. Some investigators have suggested the possibility of tumor induction like as pheochromocytoma due to the hypoxic condition. The hypoxic state stimulates catecholamine secretion from the adrenal medulla, and chronic endocrine hyperreactivity may lead to hyperplasia and neoplasia [9]. Several cases have reported the association of pheochromocystoma and heart disease [10].

The present patient had a history of congenital heart disease and came to the ER for treatment of dyspnea and mild cyanosis. The patient's heart rate and blood pressure remained high, despite medication for heart disease. Pheochromocytoma was masked by the cardiac surgery history and the tumor was subsequently detected on the basis of laboratory test findings and abdominal CT. The tumor was surgically removed and the patient experienced no postoperative complications.

In conclusion, pheochromocytoma is rare and presents variable symptoms. It will be helpful for us to think of endocrinologic disease like extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma, in cases presenting with palpitation and high blood pressure, even with a past history cardiac surgery.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Para-aortic mass (arrow) is well defined on computed tomography (A) and metaiodobenzylguanidine test (B). |

References

1. Marelli AJ, Mackie AS, Ionescu-Ittu R, Rahme E, Pilote L. Congenital heart disease in the general population: changing prevalence and age distribution. Circulation. 2007. 115:163–172.

2. Pham TH, Moir C, Thompson GB, Zarroug AE, Hamner CE, Farley D, et al. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma in children: a review of medical and surgical management at a tertiary care center. Pediatrics. 2006. 118:1109–1117.

3. Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL. Sabiston textbook of surgery: the biological basis of modern surgical practice. 2007. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders.

4. Yoshida T, Ishihara H. Pheochromocytoma presenting as massive hemoptysis and acute respiratory failure. Am J Emerg Med. 2009. 27:626.e3–626.e4.

5. Park SJ, Kim YS, Cho HR, Kwon TW. Huge carotid body paraganglioma. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011. 81:291–294.

6. Sinha S, Sharma MC, Sharma BS. Malignant paraganglioma of the sellar region mimicking a pituitary macroadenoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2008. 15:937–939.

7. Bhattacharya A, Mittal BR, Bhansali A, Radotra BD, Behera A. Cervical paraganglioma mimicking a parathyroid adenoma on Tc-99m sestamibi scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med. 2006. 31:234–236.

8. Wu MH, Chen HC, Lu CW, Wang JK, Huang SC, Huang SK. Prevalence of congenital heart disease at live birth in Taiwan. J Pediatr. 2010. 156:782–785.

9. de la Monte SM, Hutchins GM, Moore GW. Peripheral neuroblastic tumors and congenital heart disease. Possible role of hypoxic states in tumor induction. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1985. 7:109–116.

10. Kelley SR, Goel TK, Smith JM. Pheochromocytoma presenting as acute severe congestive heart failure, dilated cardiomyopathy, and severe mitral valvular regurgitation: a case report and review of the literature. J Surg Educ. 2009. 66:96–101.

ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download