Abstract

Mucormycosis is a fatal opportunistic fungal infection that typically occurs in immunocompromised patients. The classical manifestation of mucormycosis is a rhinocerebral infection, and although primary gastrointestinal infection is uncommon, it has an extremely high mortality rate in immunocompromised patients. Furthermore, cases of gastrointestinal mucormycosis in an immunocompetent host are rarely reported. Here, we describe our experience of a male patient, with no underlying disease, who succumbed to a bowel infarction caused by intestinal mucormycosis during mechanical ventilatory care for severe pneumonia and septic shock.

Mucormycosis is a fatal opportunistic fungal infection that typically occurs in immunocompromised patient. Rarely it can occur in immunocompetent patients. We report a case of intestinal mucormycosis occurred in immunocompetent patient.

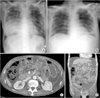

A 69-year-old man without underlying disease developed a productive cough 5 days before visiting Chungbuk National University Hospital. He was prescribed cold medicine in a local clinic. The day before visiting our hospital, he had fever, chills, breathlessness, and pain in the right chest wall, and thus, he visited our emergency room. He was a farmer who had smoked for 25 years. On arrival in the emergency room, he was alert, with a blood pressure of 90/60 mmHg, a pulse rate of 84/min, a body temperature of 37.1℃, and an oxygen saturation of 79% on room air. Crackles were heard in both lower lung fields on auscultation. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed a pH of 7.434, a carbon dioxide partial pressure of 34.9 mmHg, an oxygen partial pressure of 41.0 mmHg, bicarbonate of 23.6 mmol/L, and oxygen saturation of 78.3%. His white blood cell count was 1,710/µL, hemoglobin 14.6 g/dL, hematocrit 45.1%, and platelet count 122,000/µL. He had leucopenia but no hematologic disease and this leucopenia recovered spontaneously. Blood chemistry showed; urea nitrogen 27 mg/dL, creatinine 1.4 mg/dL, total protein 5.8 g/dL, albumin 3.5 g/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 28 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 20 IU/L, and C-reactive protein 11.40 mg/dL. Prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time were normal at 11.9 and 34.7 seconds, respectively. An initial chest X-ray showed haziness in both lower lung fields (Fig. 1A).

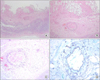

After admission, the patient experienced respiratory distress, and thus endotracheal intubation was performed. He was then transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) and received mechanical ventilator support, and was administered ciprofloxacin and piperacillin/tazobactam. After 2 days in ICU, the patient was hypoxic despite a FiO2 of 1.0, and showed septic shock despite the administrations of inotropic agents. Subsequently, his pneumonia improved progressively until on the 7th day based on his oxygen demand, blood examination, and radiographic findings (Fig. 1B). On day 12, after suprapubic catheter insertion, he suffered abdominal pain. Abdominal computed tomography was performed and showed fluid and reduced contrast enhancement indicating edema in the proximal large intestine (Fig. 1C, D). Consequently, exploratory laparotomy was performed. At surgery, a large fluid collection was observed in the abdominal cavity with necrosis of the colon from the ileocecal valve to the upper rectum, but without bowel perforation. With the exception of some inflammatory change, the small bowel was normal. Subtotal colectomy and ileostomy were performed. He was thought to have developed hypoxic damage of the bowel during initial hospitalization, but a tissue examination during the active treatment of septicemia and acute renal failure, revealed colonic infarction due to mucormycosis (Fig. 2). Consequently, he was given amphotericin B beginning at 7 days postoperatively, but unfortunately, his condition deteriorated and he died at 34 days postoperatively.

Mucormycosis is an infection caused by fungal agents in the order Mucorales. The fungi occur in air, soil, and food, and are filamentous organisms consisting of broad irregular hyphae. Infection is commonly due to Rhizopus (47%), Rhizomucor, Absidia, and Mucor species, in the family Mucoraceae. Sporangiospores are typical infective forms, whereas angio-invasive hyphal forms are responsible for tissue invasion and dissemination. The invasion of blood vessels by hyphae leads to arterial thrombosis, tissue infarction, and necrosis, whereas venous invasion causes hemorrhages [1]. Paltauf [2] reported the first case of mucormycosis in 1885. In Korea, Lee et al. [3] reported disseminated mucormycosis in 1984.

Mucormycosis is classified into rhinocerebral, pulmonary, cutaneous, gastrointestinal, central nervous system, and disseminated/miscellaneous types based on its clinical presentation and the body site involved. Of these, the gastrointestinal type constitutes only 7% of cases, but its reported mortality is around 85% [1,4], and its incidence is increasing [4].

Initial manifestations of gastrointestinal mucormycosis are abdominal pain and distension, fever, and hematochezia, and the most frequent presentations are perforation, bleeding, and epigastric distention. Serologic tests currently have no role in the diagnosis of mucormycosis, and the gold standard for diagnosis is the detection of tissue invasion by hyphae in a specimen [5]. Treatment involves the elimination of any risk factors, surgical debridement or resection, and the use of antifungal agents.

Mucormycosis usually occurs in immunocompromised patients with a severe systemic disease, such as, diabetes, renal failure, malnutrition, a malignant tumor, tuberculosis, syphilis, leukemia, or lymphoma, and in those taking steroids or on immunosuppressive therapy after transplantation [6,7].

Few cases of gastrointestinal mucormycosis in immunocompetent patients have been reported [8-10]. Two cases have been reported in purely immunocompetent patients, five cases related to trauma or clinical conditions (Table 1).

Physicians experience difficulties detecting and diagnosing intraabdominal problems in critically ill patients on mechanical ventilator support with an endotracheal tube while sedatives are administered.

In this described case, a patient with normal immunity developed colonic infarction while being treated in the ICU for pneumonia and septic shock. We initially considered that the ischemic damage was due to his shocked state, but the cause was eventually revealed to be the angioinvasive intestinal mucormycosis.

Although a patient with no underlying disease, previously or with no evidence of immunocompromised state, develops unexplained abdominal distension or pain, aggressive efforts should be made to diagnose the cause, and unusual causes, like mucormycosis, should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1(A) Initial chest radiograph showing haziness in both lungs, especially in right lower lung field. (B) Chest radiograph taken after 7 days in intensive care unit (ICU) showing reduced haziness. (C, D) Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography images after 12 days in ICU showing lack of colon wall enhancement and fluid collection. |

| Fig. 2(A-C) Microscopic findings of resected colon. Microscopic findings of colon showing transmural infarction. Invasive fungal hyphae were observed in all layers of colon wall, especially in arterial wall (center). Fungal invasion of arterial wall was accompanied by arterial thrombosis (A: H&E, ×100; B: H&E, ×200; C: H&E, ×400). (D) Gomori's methenamine-silver stain of artery showing thick walls, noncircular cross-section, and nonseptated hyphae (×400). |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a research grant from Chungbuk National University in 2010.

References

1. Kontoyiannis DP, Lewis RE. Invasive zygomycosis: update on pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and management. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006. 20:581–607. vi.

2. Paltauf A. Mycosis mucorina. Virchows Arch. 1885. 102:543–564.

3. Lee HB, Bilinsky RT, Maher CC. Disseminated mucormycosis: a complication of kidney transplantation. Korean J Nephrol. 1984. 3:91–95.

4. Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, Knudsen TA, Sarkisova TA, Schaufele RL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005. 41:634–653.

5. Lehrer RI, Howard DH, Sypherd PS, Edwards JE, Segal GP, Winston DJ. Mucormycosis. Ann Intern Med. 1980. 93:93–108.

6. McNulty JS. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: predisposing factors. Laryngoscope. 1982. 92(10 Pt 1):1140–1143.

7. Meyer RD, Rosen P, Armstrong D. Phycomycosis complicating leukemia and lymphoma. Ann Intern Med. 1972. 77:871–879.

8. Shiva Prasad BN, Shenoy A, Nataraj KS. Primary gastrointestinal mucormycosis in an immunocompetent person. J Postgrad Med. 2008. 54:211–213.

9. Carr EJ, Scott P, Gradon JD. Fatal gastrointestinal mucormycosis that invaded the postoperative abdominal wall wound in an immunocompetent host. Clin Infect Dis. 1999. 29:956–957.

10. Maravi-Poma E, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, de Jalon JG, Manrique-Larralde A, Torroba L, Urtasun J, et al. Outbreak of gastric mucormycosis associated with the use of wooden tongue depressors in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2004. 30:724–728.

ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download