Abstract

Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS) is a rare systemic vascular disorder characterized by multiple venous malformations involving many organs. BRBNS can occur in various organs, but the most frequently involved organs are the skin and gastrointestinal (GI) tract. GI lesions of BRBNS can cause acute or chronic bleeding, and treatment is challenging. Herein, we report a case of GI BRBNS that was successfully treated with a combination of intraoperative endoscopy and radical resection.

Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS) is a rare systemic vascular disorder characterized by multiple venous malformations, such as hemangioma, involving many organs [1]. Approximately 200 cases of BRBNS including 13 Korean cases have been reported since Gascoyen's first presentation in 1860 [2]. BRBNS can occur in various organs, such as skeletal muscle, joints, liver, lung, eye, kidney, and the central nervous system [1,2]. However, the most frequently involved organs are the skin and gastrointestinal (GI) tract [1,2]. GI lesions of BRBNS can cause acute or chronic bleeding, and treatment is challenging. Herein, we report a case of GI BRBNS that was successfully treated with a combination of intraoperative endoscopy and radical resection.

A 20-year-old female patient was transferred to Samsung Medical Center with the suspicion of bleeding colonic hemangioma. She denied hematochezia or melena. She did not have any significant family history. Her vital signs were stable. Initial serum hemoglobin level was 10.2 g/dL and hematocrit was 27.5%. Other laboratory findings were unremarkable.

However she had visited another hospital with syncope six months before visiting Samsung Medical Center. At the time of her syncopal episode, blood transfusion was administered because her serum hemoglobin level was 5 g/dL. Fecal occult blood test result was positive. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy/colonoscopy revealed that she has colonic hemangioma.

She had been born with a cutaneous vascular malformation on her right elbow. When she was 22 months old, she underwent the first excision of the malformation. After that operation, the vascular lesion recurred after two years; therefore, she underwent re-resection of the mass. However, the mass recurred again after two years, and she also had limited motion of the elbow due to deformity. She had no other cutaneous lesions. When she was 12 years old, she was diagnosed with iron deficiency anemia and began taking iron supplements.

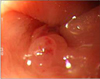

She underwent colonoscopy, and a 0.5 cm hemangioma was found in the sigmoid colon. There was no evidence of bleeding (Fig. 1). The entire colon to the ileocecal valve was observed, and there was no other abnormality. Band ligation was performed for the lesion. Double-balloon upper endoscopy was performed in order to identify other GI lesions. The small intestine was explored to the proximal jejunum, and three hemangiomas were found (Fig. 2). Two hemangiomas had mucosal erosions, the most proximal of which was located at the duodenojejunal junction. Tattooing was performed on the most distal and proximal lesions, respectively

We planned for intraoperative endoscopy and surgical resection. The laparotomy was performed with a midline incision. A total of seven hemangiomas were found, including the three hemangiomas that had already been identified (Fig. 3). The four other hemangiomas were identified in the portion of the intestine distal to the tattooed point during careful inspection and intraoperative endoscopy via the transected intestine. All of the involved lesions were resected. Segmental resection and end-to-end anastomosis was performed for two segments that had two close hemangiomas, and wedge resection followed by primary closure was performed for the other sporadic lesions. The entire small intestine was probed, but there were no other lesions. The patient was uneventfully discharged on the seventh postoperative day. She was healthy and did not have any other symptoms or signs during the six-month follow-up period.

BRBNS is also called cutaneous cavernous hemangioma or Bean syndrome [2]. Although autosomal dominant inheritance of the BRBNS has been identified in several familial cases with a linkage to a chromosome 9p locus, the majority of cases are sporadic, and the etiology and pathogenesis of this syndrome remain unknown [1]. The differential diagnosis of GI hemangiomatosis include BRBNS, Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome, Maffucci syndrome, and Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome [3,4]. Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome is characterized by recurrent epistaxis, telangiectasia, and its autosomal dominant inheritance. Maffucci syndrome also accompanies enchodromas/lymphangiomas. The three main features of Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome are nevus flammeus, venous/lymphatic malformation, and soft-tissue hypertrophy. Therefore, the diagnosis of BRBNS was made for the current patient.

It is known that BRBNS does not have a sex predilection and can occur at any age [5]. The morbidity and mortality depend upon the extent and number of visceral lesions, and most of the problematic cases involve severe intestinal bleeding [6].

An overview of 39 patients with BRBNS revealed the involved organs as skin (39 patients), GI tract (31 patients), brain (7 patients), joints (2 patients), liver (2 patients), eye (1 patient), kidney (1 patient), and spleen (1 patient) [7]. Brain lesions can cause cranial neuropathy; therefore, presymptomatic evaluation of the brain, such as magnetic resonance imaging, is necessary [8]. The skin lesions usually do not cause problems aside from cosmetic concerns [2]. However, joint lesions can be troublesome, as in our patient.

GI BRBNS can be variable with respect to location and the number and forms of the lesions. GI hemangioma is most common in the small intestine (100%), followed by the colon (74%) and stomach (26%), but it can involve any portion of the GI tract with anywhere from several to several hundred lesions [5,7]. Although the association is not definite due to the rarity of BRBNS, there seems to be a positive correlation between the number of GI lesions and the number of cutaneous hemangiomas [7]. This is consistent with the relatively small number of GI lesions in our patient. GI BRBNS can arise in diverse forms, including polylobulated, nodular, sessile, pedunculated, or ulcerated [1,2].

The symptoms or signs of GI BRBNS may be different according to the locations of the lesion and can include vague abdominal pain, chronic anemia or consumptive coagulopathy, intussusception, volvulus, intestinal infarction, melena or hematochezia, and in the worst case, hypovolemic shock caused by overt GI bleeding from ruptured GI lesions [1,2].

For GI BRBNS, endoscopy is the first-line diagnostic tool and enables immediate therapeutic options. Nevertheless, other diagnostic modalities, such as double-balloon endoscopy or capsule endoscopy, may be necessary because GI BRBNS can be located anywhere in the small intestine, and the whole intestine cannot be observed by conventional endoscopy.

The treatment of GI BRBNS is determined by the extent of intestinal involvement and severity of the disease. If there is no bleeding from the lesions, GI BRBNS can be closely observed. However, there is debate over the optimal treatment of bleeding events. If bleeding occurs from a GI BRBNS lesion, some authors suggest conservative treatment, such as iron replacement, transfusion, or endoscopic intervention, for minor or intermittent bleeding. Conversely, others insist on the need for surgical intervention for overt bleeding. This logic seems convincing at first glance. However, even if the bleeding is minor, if it is continuous, iron replacement or transfusion can be life-long therapy. This is expensive and decreases quality of life. GI hemangioma of BRBNS is occasionally transmural [2]. Although some authors suggest they produce good clinical outcomes, endoscopic interventions, such as argon plasma coagulation, band ligation, electrocauterization, or histoacryl injection to the relatively thin small intestinal wall, can cause bowel perforation or rebleeding [7,9]. For overt bleeding, it is very difficult to localize the bleeding vessel because of the large amount of intraluminal blood. In a life-threatening situation, surgery may be the only option. These are not favorable circumstances under which to perform surgery, but it may be an inevitable choice. Meanwhile, surgical elimination with wedge or segmental resection of the small intestine has safe perioperative outcomes and sustained clinical remission according to recent reports [7,10]. In sum, early surgical intervention may be justified for bleeding GI BRBNS before severe bleeding occurs. Two conditions must be satisfied for the ideal surgical resection: 1) the number and distribution of the GI lesions should be identified, for which intraoperative endoscopy via transected intestine is an excellent method; and 2) GI lesions should not be too extensive. If hundreds of GI lesions are distributed evenly throughout the entire intestine, surgical resection cannot be considered because of the risk of short bowel syndrome. Capsule endoscopy can play an important role in determining surgical resectability. The double-balloon enteroscopy was only able to reach the proximal jejunum in this case and seems to have inconsistent outcomes depending on anatomical diversity and the endoscopist.

Gastric or colonic hemangiomas without small intestinal lesion can be easily resected by endoscopic procedures, but the surgical resection should be considered in the case of small intestinal hemangiomas due to the difficulties and risks in the endoscopic procedures.

For the patient, considering her medical history, her chronic iron deficiency anemia was thought to be originated from bleeding of intestinal hemangioma. Although we knew the necessity of the whole intestine examination, the double-balloon upper endoscopy only allowed us to reach upto the proximal jejunum rather than the whole intestine. However, based on the double-balloon endoscopy result, we did not anticipate intestinal hemangiomas to diffuse numerously in the area so that it is unresectable.

The pathologic findings revealed large, blood-filled caverns lined by a single endothelial layer with surrounding thin connective tissue, consistent with cavernous hemangiomas. Only one malignant change in a cutaneous lesion has been reported, but there has been no malignant transformation of GI BRBNS [1].

Here, we reported a case of GI BRBNS that was successfully cured by endoscopic resection, intraoperative endoscopy, and surgical resection. All BRBNS patients should be observed carefully due to the risk of lethal bleeding. One should perform medical or surgical intervention based on the clinical symptoms and signs and the extent of the disease. A multidisciplinary approach is helpful to determine the extent of the disease and the therapeutic plan.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1A 0.5 cm hemangioma was found in the sigmoid colon without evidence of bleeding on colonoscopy. |

| Fig. 2The small intestine was explored to the proximal jejunum, and three hemangiomas were found. Two hemangiomas had mucosal erosions. (A) The most proximal hemangioma was located in the duodenojejunal junction. (B) The middle hemangioma. (C) The most distal hemangioma was found in the proximal jejunum. |

References

1. Domini M, Aquino A, Fakhro A, Tursini S, Marino N, Di Matteo S, et al. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome and gastrointestinal haemorrhage: which treatment? Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2002. 12:129–133.

2. Hasosah MY, Abdul-Wahab AA, Bin-Yahab SA, Al-Rabeaah AA, Rimawi MM, Eyoni YA, et al. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: extensive small bowel vascular lesions responsible for gastrointestinal bleeding. J Paediatr Child Health. 2010. 46:63–65.

3. Shepherd V, Godbolt A, Casey T. Maffucci's syndrome with extensive gastrointestinal involvement. Australas J Dermatol. 2005. 46:33–37.

4. Shovlin CL, Guttmacher AE, Buscarini E, Faughnan ME, Hyland RH, Westermann CJ, et al. Diagnostic criteria for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome). Am J Med Genet. 2000. 91:66–67.

5. Deng ZH, Xu CD, Chen SN. Diagnosis and treatment of blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome in children. World J Pediatr. 2008. 4:70–73.

6. Agnese M, Cipolletta L, Bianco MA, Quitadamo P, Miele E, Staiano A. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. Acta Paediatr. 2010. 99:632–635.

7. Wong CH, Tan YM, Chow WC, Tan PH, Wong WK. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: a clinical spectrum with correlation between cutaneous and gastrointestinal manifestations. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003. 18:1000–1002.

8. Tomelleri G, Cappellari M, Di Matteo A, Zanoni T, Colato C, Bovi P, et al. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome with late onset of central nervous system symptomatic involvement. Neurol Sci. 2010. 31:501–504.

9. Ng WT, Wong YT. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: more lessons to be learnt. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2007. 17:221–222.

10. Kopacova M, Tachecí I, Koudelka J, Kralova M, Rejchrt S, Bures J. A new approach to blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: the role of capsule endoscopy and intra-operative enteroscopy. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007. 23:693–697.

ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download