Abstract

Purpose

There are no guidelines for the optimal timing of the decision of when to perform completion thyroidectomy, and controversy exists regarding how the timing of completion thyroidectomy impacts survival patterns. We investigated the legitimacy of an observational strategy in central node metastasis after thyroid lobectomy for papillary thyroid cancer (PTC).

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated 522 consecutive patients who underwent thyroid lobectomy. Of the 69 patients with central metastasis, 61 patients (88.4%) were included in an observational study under cautious evaluation with informed consent by the patients, and compared with an observation arm of 180 postlobectomy N0 (node negative proven) patients.

Results

Of the 522 patients, six (1.1%) thyroid, five (0.9%) central, and two (0.4%) lateral recurrences were observed. Lateral recurrences occurred in the immediate completion N0 and Nx groups but not in the N1a observation arms. There were two (3.3%) central recurrences without thyroid or lateral recurrence on the observation arm of N1a observation patients. But two (1.1%) thyroid and three (1.7%) central recurrences were on the observation arm of N0 patients. In Kaplan-Meier survival curves for central or lateral recurrences between observation arms for the N1a and N0 groups, no significant difference was found between the N1a and N0 observation arms (P = 0.365).

Two major sets of guidelines for thyroid lobectomy and completion thyroidectomy, those of the American Thyroid Association (ATA) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)-in which there is considerable overlap of committee members and authors-have differing recommendations for the extent of surgery in papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) [1,2]. The former strongly recommends total thyroidectomy for tumors greater than 1.0 cm, while the latter considers lobectomy to be sufficient in patients with intrathyroidal tumors less than 4.0 cm [3]. Considerable controversies exist regarding when to perform a completion thyroidectomy in central metastasesproven lobectomy patients.

In the past, it was common practice to perform immediate completion thyroidectomy if the harvested nodes were proven to have metastasized after thyroid lobectomy. But some patients desired to be observed over a period of time, even though there was a possibility of relapse. However, there are no guidelines for the timing of the decision to perform completion thyroidectomy. So we evaluated the recurrence in the observational group with central metastasis proven after thyroid lobectomy without an immediate completion thyroidectomy, and legitimacy of an observational strategy in central node metastasis after thyroid lobectomy for PTC.

We retrospectively reviewed 522 consecutive patients who underwent thyroid lobectomy due to PTC between May 2004 and April 2008 in Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital. Though the indications for thyroid lobectomy in ATA and NCCN guidelines were generally kept, there were some exceptions in our study. Patients over 45 years of age and with incidentally detected multiple thyroid cancer were included. Surgical procedures were performed with classic low cervical incision, minimal invasive lobectomy, and via the endoscopic approach [4]. Minimal invasive type lobectomy was done through an ipsilateral 3.0-cm incision, and the endoscopic approach was performed as the bilateral axillo-breast type [5]. Ipsilateral central neck dissection following thyroid lobectomy was done on high risk patients, but not prophylactic in all patients. Patients were followed up at 3- to 6-month intervals during the first two postoperative years and annually thereafter for early detection of local or systemic recurrence. At each visit, we took careful history of hypothyroidism symptoms and checked serum thyroid hormone levels [4].

We divided the patients into four subgroups: two arms, immediate completion versus observational strategy, with two groups each according to whether central node metastasis occurred after lobectomy, that is, N0, and N1a. The analyses were mainly on observation arm, especially for the N1a and N0 groups; 61 patients were observed without completion thyroidectomy after thyroid lobectomy but proven central metastases. After thyroid lobectomy, 21.1% in benign conditions developed hypothyroidism in Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital [4]. In malignant settings, we routinely prescribed thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) suppressive therapy during the first year, then levothyroxine replacement therapy for low-risk malignancy patients.

We used the t-test to compare continuous variables between each group and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Binary logistic regression test was used for multivariate analysis of statistically significant variables from the univariate analysis. Survival curves for central or lateral neck recurrence, except thyroid recurrences, were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. We used proportional hazards modeling of the relative survival to assess the effects of clinicopathologic factors. Results were analyzed using PASW ver. 18.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was defined as a P-value less than 0.05 (P < 0.05), and any hazard ratio (HR) greater than 1.0 indicated worsened prognosis.

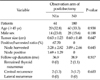

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 522 enrolled PTC patients. Though we generally tried to keep the indications for thyroid lobectomy in ATA [1] and NCCN [2] guidelines, there were some additional inclusions in our study. One hundred ninety-three patients (37.0%) over 45 years of age and with incidentally detected 11 (2.1%) multiple thyroid cancer were included. The median age was 41.0 years, and 17.2% (92 patients) were male. If gross extrathyroidal extension was suspected, immediate conversion to total thyroidectomy was performed and the patient was excluded from this study; there were 55 (10.5%) microscopic capsular invasion and 16 (3.1%) isthmic resection margin invasion. Median tumor size was 0.5 cm (range, 0.1 to 4.5 cm). The median follow-up duration was 42.0 months (range, 3.0 to 93.0 months). Ipsilateral central neck dissection following thyroid lobectomy was done on high risk patients, but not prophylactic in all patients. Central node dissection was performed in 258 (49.4%), and there were 69 (13.2%) N1a, 182 (34.9%) N0, and 283 (54.2%) Nx stage patients after lobectomy (Table 1).

Of the 522 patients excluding 10 follicular and two medullary carcinomas, 34 (6.5%) underwent completion thyroidectomy for the remaining thyroid, central, and lateral neck recurrence. There were 21 immediate (61.8%) and 13 delayed (38.2%) completion thyroidectomies (Fig. 1). Immediate completion thyroidectomy was defined as occurring within three months after initial lobectomy. Immediate completion thyroidectomy was performed due to missed PTC (6 cases), positivity of margin or lymphovascular invasion (5 cases), disease free but required additional radioactive iodine therapy (15 cases) and remaining central metastases (10 cases).

In the past, we recommended routine completion thyroidectomy immediately or within three months after initial thyroid lobectomy in high risk patients. However, some patients desired observation over a period of time, even though this offered the possibility of relapse. The desire for and proportion of observational study was higher in the minimal invasive type compared with the classic type or endoscopic approach lobectomy, although this was not statistically significant (P = 0.183).

Fig. 1 and Table 2 shows the patterns of central or lateral recurrence in the two arms for each of the three nodal groups after thyroid lobectomy, Follicular and medullary carcinoma patients were excluded from further analysis. In the observation arm of lobectomy Nx, there were four thyroid and two central recurrences, and in the observation arm of N0, there were five (2.8%) delayed completions. Three recurred papillary thyroid carcinomas on remaining thyroid developed in the 15th, 27th, and 57th months. Three (1.7%) central recurrences developed in the 9th, 23rd, and 57th months. In immediate completion arm of N1a, there was no recurrence. But in the observation arm of lobectomy N1a, there were two delayed completions (3.3%) and confirmed central recurrences in the 11st and 33rd months later after initial lobectomy. A total of six thyroid, five central, and two lateral recurrences were observed in a median of 42.0 months. Lateral recurrences occurred in the 46th month after immediate completion in the N0 group and in the 30th month after immediate completion in the Nx group, but did not occur in the N1a observation arm (Table 2).

In four arms of N1a and N0 patients, two observation arms of N1a and N0 patients were further analyzed. Age (P = 0.938), sex (P = 0.188), tumor size (0.63 cm vs. 0.60 cm, P = 0.647) and follow-up period were not significantly different. The N1a observation arm (n = 61) was statistically equivalent to the N0 observation arm (n = 180) for central or lateral recurrence (Table 3). We assumed central metastasis after thyroid lobectomy and higher ratio of positive nodes over harvested node to be factors for central or lateral recurrence, as recommended in the ATA [1] and NCCN [2] guidelines. But the ratio of the harvested central nodes did not show a significant difference between the immediate completion arm versus the observation arm within N1a groups (62.5% vs. 67.7%, P = 0.583).

Fig. 2 displays the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for central or lateral recurrences between observation arms in the N1a versus N0 group; it has not been adjusted for tumor size less than 1.0 cm. Even by excluding subgroup analysis for tumors 1 cm or larger, no significant difference was found between the N1a versus N0 observation arms (P = 0.365) within the 42.0-month follow-up period.

We used Cox proportional hazards modeling of the central or lateral recurrence after thyroid lobectomy (Table 4). Indeterminate contralateral thyroid tumor masses were identified on retrospective radiologic review, so remaining thyroid recurrences were excluded from the event of recurrence.

Using data from 399 PTC patients with full details on both central and lateral recurrences, age over 45 years old (HR, 1.54; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.24 to 9.92; P = 0.652), male (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.09 to 9.06; P = 0.943), and TSH suppression vs. levothyroxine replacement after one year TSH suppression (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.87 to 3.80; P = 0.566) were not significant. Surprisingly, the N1a observation arm was not associated with a significantly worse prognosis for recurrences compared with the N0 observation arm (HR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.04 to 2.77; P = 0.308 in univariate analysis / HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.06 to 5.69; P = 0.643 in multivariate analysis).

Because most survivors of PTC have a long life expectancy, it is important to understand how differences in clinical, pathologic and treatment characteristics alter their survival risk profiles. Surprisingly, although controlling for the remaining variables, including tumor size, the surgical strategies of lobectomy and thyroidectomy did not reveal any differences in overall survival or disease-specific survival. Even by performing subgroup analysis for tumors 1 cm or larger, no significant difference was found between the surgical groups of lobectomy versus total thyroidectomy [6]. This controversy persists because there have been no meaningful long-term randomized controlled trials.

After analyzing 522 consecutive PTC patients who underwent lobectomy since opening Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital in May 2007, no improvement was demonstrated with immediate completion versus observation in the N1a group after thyroid lobectomy. The benefit of completion thyroidectomy in the N1a groups was unclear. In the past, immediate completion thyroidectomy was common practice if the harvested node was proven to involve metastatic lymph nodes after thyroid lobectomy. One has to weigh these very slight survival differences against the potential complications of a more aggressive surgery. The potential surgical complications that can occur with completion thyroidectomy include postoperative hypoparathyroidism and recurrent laryngeal nerve injury [7].

However, there are no guidelines for the optimal timing of the decision of when to perform completion thyroidectomy, and controversy exists regarding how the timing of completion thyroidectomy impacts survival patterns. Our findings herein suggest that perhaps it is time for a subtle paradigm shift in our approach to well-differentiated thyroid papillary carcinomas.

Retrospective studies have shown that recurrence within the thyroid bed is reduced in patients who have a total thyroidectomy compared with those treated with less than total thyroidectomies [8,9]. However, multivariate analysis revealed that immediate completion thyroidectomy does not impact significant central or lateral recurrence. Although this study supports no statistically significant difference between N1a observation arms versus N0 observation arms, the results of our study compel us to reinvestigate the current immediate completion thyroidectomy recommendations based on nodal metastasis. This may not be a factor for central or lateral recurrence, and more tailored treatment strategy for individual patients, as opposed to individual tumor criteria, should be explored.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has identified legitimacy for observational study of lobectomy N1a, but median three and one half years follow-up may still not be very long for outcome studies of PTC, and further studies are needed to elucidate their long term recurrence or survival. This study is limited by its retrospective nature, by the four surgeons who performed the operations, and by the lack of randomized, prospective selection of optimal patients. It has been suggested that access to an experienced thyroid surgeon may be one of the factors most predictive of outcome [10]. A prospective trial, randomized according to observation or completion strategy and to nodal status after lobectomy such as N1a versus N0 groups, would require many thousands of patients and is unlikely to be performed in the near future. Even if such a study were feasible, it would be difficult to control for surgical technique and surgeon expertise.

Therefore we recommend that treatment should continue to be individualized for each patient by taking into account the potential risks of central and lateral recurrence. Follow-up without completion thyroidectomy would be performed carefully in central metastases-proven patients after lobectomy with PTC. We think that the timing of the decision as to when perform completion thyroidectomy should be based on the patient's risk category and desires.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Follow-up of 522 patients underwent lobectomy due to papillary thyroid cancer. CLND, central lymph node dissection. |

| Fig. 2Kaplan-Meier survival curves for central or lateral recurrences according to observation arm of N1a versus N0 groups (P = 0.365, log-rank test). |

ACKNOWLEGEMENTS

Supported by a grant (CRI 10030-1) from the Chonnam National University Hospital research institute of clinical medicine.

Notes

References

1. American Thyroid Association (ATA) Guidelines Taskforce on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, Kloos RT, Lee SL, et al. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009. 19:1167–1214.

2. Sherman SI, Angelos P, Ball DW, Byrd D, Clark OH, Daniels GH, et al. Thyroid carcinoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007. 5:568–621.

3. Shaha AR. Extent of surgery for papillary thyroid carcinoma: the debate continues: comment on "surgery for papillary thyroid carcinoma". Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010. 136:1061–1063.

4. Cho JS, Shin SH, Song YJ, Kim HK, Park MH, Yoon JH, et al. Is it possible to predict hypothyroidism after thyroid lobectomy through thyrotropin, thyroglobulin, anti-thyroglobulin, and anti-microsomal antibody? J Korean Surg Soc. 2011. 81:380–386.

5. Choe JH, Kim SW, Chung KW, Park KS, Han W, Noh DY, et al. Endoscopic thyroidectomy using a new bilateral axillo-breast approach. World J Surg. 2007. 31:601–606.

6. Mendelsohn AH, Elashoff DA, Abemayor E, St John MA. Surgery for papillary thyroid carcinoma: is lobectomy enough? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010. 136:1055–1061.

7. Hay ID, Bergstralh EJ, Goellner JR, Ebersold JR, Grant CS. Predicting outcome in papillary thyroid carcinoma: development of a reliable prognostic scoring system in a cohort of 1779 patients surgically treated at one institution during 1940 through 1989. Surgery. 1993. 114:1050–1057.

8. Hay ID. Papillary thyroid carcinoma. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1990. 19:545–576.

9. DeGroot LJ, Kaplan EL, McCormick M, Straus FH. Natural history, treatment, and course of papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990. 71:414–424.

10. Sherman SI. The risks of thyroidectomy: words of caution for referring physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 1998. 13:60–61.

ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download