Abstract

Purpose

We evaluated the risk factors for late complications and functional outcome after total proctocolectomy (TPC) with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) for ulcerative colitis (UC).

Methods

Pre- and postoperative clinical status and follow-up data were obtained for 55 patients who underwent TPC with IPAA between 1999 and 2010. The median follow-up duration was 4.17 years. Late complications were defined as those that appeared at least one month after surgery. For a functional assessment, telephone interviews were conducted using the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale. Twenty-eight patients completed the interview.

Results

Late complications were found in 20 cases (36.3%), comprising pouchitis (n = 8), bowel obstruction (n = 5), ileitis (n = 3), pouch associated fistula (n = 2), and intra-abdominal infection (n = 2). The preoperative serum albumin level for patients with late complications was lower than for patients without (2.4 ± 0.5 vs. 2.9 ± 0.7, P = 0.04). Functional outcomes were not significantly associated with clinical characteristics, follow-up duration, operation indication, or late complications.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) was rare in Korea until the 1980s. The annual incidence of UC sharply increased from 0.20/100,000 people between 1986 and 1988 to 1.23/100,000 people between 1995 and 1997 according to national public epidemiologic research [1].

UC is a complex chronic disease that is characterized by relapsing and remitting acute ulcerating inflammation of the colorectal mucosa. Although our knowledge has greatly improved over the last decades, the optimal management of UC has yet to be elucidated. For this reason, treatment largely remains unspecific and primarily directed toward relieving symptoms. Approximately 30 to 45% of patients with UC require operative treatment at some point [2]. The indications for operation were intractable disease, toxic megacolon, bowel perforation, and dysplasia or cancer in long-standing UC.

A total proctocolectomy (TPC) with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) is considered the surgery of choice for definitive UC management because it removes the diseased bowel, reduces the cancer risk, and preserves a natural route for defecation. Although most patients report a marked improvement in their disease symptoms and quality of life (QoL) after surgery, more than 40% of patients experience late complications [3]. The late complications include pouchitis, pouch-associated fistula, bowel obstruction and intra-abdominal infection, and are closely related to functional outcome and QoL [3,4].

Many studies have evaluated the outcome of TPC with IPAA in western countries, but they are rare in Korea. In this study we evaluated the risk factors for late complications in UC patients at our center. We also evaluated the functional outcome and satisfaction after surgery in these patients.

A total of 55 patients underwent TPC with IPAA at the Samsung Medical Center between January 1999 and December 2010. The charts of all patients were reviewed to determine clinical characteristics, including gender, age at operation, disease duration prior to operation, number of preoperative medications, duration of follow-up, associated malignancy, underlying disease, extra-intestinal manifestations, smoking behavior, surgical indications, disease extent and presence of immediate postoperative complications or late complications.

Postoperative complications were defined as early if they occurred within one month and late if they occurred thereafter. Late complications were diagnosed based on patient symptoms, endoscopic findings, and imaging studies. Surgical characteristics included the type of surgery (laparoscopic versus laparotomy), staged operation, and type of anastomosis. A staged operation was defined as two or more staged operations, except for a routine ileostomy take-down operation.

To assess nutritional status, preoperative body mass index, preoperative and postoperative serum hemoglobin, albumin and cholesterol levels were checked. The postoperative laboratory data were evaluated 1 month after operation.

Disease extent was classified using the Montreal classification. The Montreal classification defines E1 as disease limited to the rectum, E2 as limited distal to the splenic flexure (distal UC), and E3 as pancolitis [5].

To assess functional outcome, telephone interviews were conducted using questionnaire that is based on the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale [4]. This questionnaire contains ten items, including nine functional variables and one psychosocial variable. Each variable was rated on a five-point scale, with 0 representing the best result and 4 the worst. The interview was performed by a researcher and the Cronbach's α was 0.674.

The clinical characteristics of all patients were compared using chi-square, Fisher's exact tests, Pearson correlation analysis, and t-tests. All analyses were performed using SAS ver. 9.13 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The threshold for statistical significance was predefined as P < 0.05.

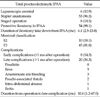

A total of 55 patients with UC (35 males/18 females) underwent TPC with IPAA with a median age at the operation of 42.5 years (range, 16 to 69 years). The median postoperative follow-up time was 4.2 years (range, 2 months to 11 years). The demographics and clinical characteristics of all 55 patients are summarized in Table 1.

Fifty four patients underwent protective ileostomy. Median time of ileostomy takedown was 6.1 months (range, 2.5 to 23.8 months) after TPC with IPAA.

Twenty patients (36.3%) experienced a late complication. The duration from operation to complication was 10.6 months (range, 1.2 to 67.0 months). The most common late complication was pouchitis and occurred in 8 patients (14.5%). Other late complications included ileus, anastomosis site bleeding, pouch-associated fistula, intra-abdominal abscess, and ileitis (Table 2).

Patient gender, age, smoking behavior, disease extent, cytomegalovirus infection, associated malignancy, underlying disease, and extra-intestinal symptoms were not statistically significant risk factors for late complications. Failure of medical treatment was the most frequent surgical indication. And the surgical indication did not affect late complications. The type of surgery and staged operation also were not significant risk factors.

Among the parameters used to assess preoperative nutritional status, only preoperative serum albumin level was lower in patients with late complications than in those without (2.4 ± 0.5 vs. 2.9 ± 0.7, P = 0.04) (Table 3). The postoperative albumin level normalized in most patients, and there were no differences between patients with and without late complications (4.2 ± 0.4 vs. 4.4 ± 0.2, P = 0.15) (Table 4).

Twenty eight patients answered telephonic interview. Four patients were excluded because the follow-up time after ileostomy takedown was less than 1 year. So, functional data were obtained from 24 of 55 patients (44%).

The median follow-up time was 28.6 months (range, 14.5 to 67.2 months). The median time of ileostomy takedown after TPC with IPAA was 5.8 months (range, 2.5 to 11.5 months). And the duration from ileostomy take down to telephonic interview was 21.7 months (range, 12.1 to 60.2 months).

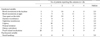

Functional results are listed in Table 5. The defecation frequency was 7.2 (range, 4.5 to 20.0). 'Bowel movements at night' was the most uncomfortable symptom (median, 3.0). 'Bowel movements in the daytime' was uncomfortable in younger patients (≤44 years). Mean total functional score of 24 patients was 15.3 (range, 3 to 26). And the scores were not significantly associated with clinical characteristics, follow-up duration, operation indication, or late complications (Tables 6, 7).

In this study we reviewed the records of 55 patients with UC who underwent TPC with IPAA between 1999 and 2010. We were especially interested in late complications and functional outcomes. The late complication rate was 36.3%, and this complication rate agrees with previous studies [6,7].

In other studies of western countries, early age of disease onset, follow-up duration, and extra-intestinal symptoms were risk factors for complications [3,8]. Emergent operation has also been found to bea risk factor [9]. However, these parameters were not significantly related to late complications in our study. A lack of data made the exact onset of symptoms difficult to determine. So age of disease onset was not obvious in our study, and could explain the lack of a relationship between early age of disease onset and late complications. The relatively short period of follow-up and low incidence of extra-intestinal symptoms could also have affected our results. The most frequent late complication was pouchitis (14.5%), which occurred less frequently than in other studies that reported about 40 to 60% patients developed at least one episode of pouchitis [3]. The short follow-up duration may explain the lower incidence of pouchitis, which increases with longer follow-up. Pouchitis is also more common in patients with an extra-intestinal manifestation. Only 4 patients in our study had an extra-intestinal symptom, which could explain the low incidence of pouchitis. There were only 2 emergent operations in our study, which is too small to establish statistical significance.

This study found low preoperative albumin level to be a risk factor for late complications after TPC with IPAA. Low serum albumin level increases postoperative mortality and morbidity in major operations. Additionally, postoperative albumin replacement therapy facilitates the earlier return of bowel movements and shortens hospital stays after colon surgery [10]. UC patients are at high risk for malnutrition, so preoperative nutritional support, especially albumin, could help decrease late complications.

QoL has become an important measure for TPC with IPAA since mortality and morbidity rates after surgical procedures have declined. Functional outcome has been reported to correlate significantly with QoL in patients who have undergone TPC with IPAA [11,12]. The functional results in our study were acceptable. Most patients had symptom relief compared to before surgery. Younger patients found 'bowel movements during the daytime' to be unacceptable, possibly because they participate in more outdoor activities. In another study, stool-related medications were significantly correlated with decreased QoL because of increased stool frequency as well as fluid consistency [13]. In our study, many patients answered that they controlled the medication on their own and it did not induce much discomfort. The low rate of pouchitis would also influence the low use of medications.

There are some limitations to this study. First, this was a retrospective study with a relatively small sample size. Prospective data collection was difficult because of the low incidence rate of UC. However, considering the increasing rate of UC, we will meet many patients in the near future. Collecting data from multiple centers could also help overcome the limitations associated with a small sample size. Our data could serve as the basis for a multicenter study.

Second, the telephone interview was performed at varying postoperative times, so follow-up duration differed for each. Additionally, there is no standard questionnaire to assess functional outcome in outpatient departments. To generate an exact functional assessment, we will perform the interview at a standard follow-up time. And a standard outpatient questionnaire will help assess and improve the functional outcome at routine follow-up visits.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Yang DH, Yang SK. Trends in the incidence of ulcerative colitis in Korea. Korean J Med. 2009. 76:637–642.

2. Kaiser AM, Beart RW Jr. Surgical management of ulcerative colitis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2001. 131:323–337.

3. Ferrante M, Declerck S, De Hertogh G, Van Assche G, Geboes K, Rutgeerts P, et al. Outcome after proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008. 14:20–28.

4. Carmon E, Keidar A, Ravid A, Goldman G, Rabau M. The correlation between quality of life and functional outcome in ulcerative colitis patients after proctocolectomy ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Colorectal Dis. 2003. 5:228–232.

5. Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006. 55:749–753.

6. Michelassi F, Lee J, Rubin M, Fichera A, Kasza K, Karrison T, et al. Long-term functional results after ileal pouch anal restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis: a prospective observational study. Ann Surg. 2003. 238:433–441.

7. Romanos J, Samarasekera DN, Stebbing JF, Jewell DP, Kettlewell MG, Mortensen NJ. Outcome of 200 restorative proctocolectomy operations: the John Radcliffe Hospital experience. Br J Surg. 1997. 84:814–818.

8. Shen B, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, Brzezinski A, Bennett AE, Lopez R, et al. Risk factors for diseases of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006. 4:81–89.

9. Heyvaert G, Penninckx F, Filez L, Aerts R, Kerremans R, Rutgeerts P. Restorative proctocolectomy in elective and emergency cases of ulcerative colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1994. 9:73–76.

10. Woods MS, Kelley H. Oncotic pressure, albumin and ileus: the effect of albumin replacement on postoperative ileus. Am Surg. 1993. 59:758–763.

11. Weinryb RM, Gustavsson JP, Liljeqvist L, Poppen B, Rossel RJ. A prospective study of the quality of life after pelvic pouch operation. J Am Coll Surg. 1995. 180:589–595.

12. Martin A, Dinca M, Leone L, Fries W, Angriman I, Tropea A, et al. Quality of life after proctocolectomy and ileo-anal anastomosis for severe ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998. 93:166–169.

13. Andersson T, Lunde OC, Johnson E, Moum T, Nesbakken A. Long-term functional outcome and quality of life after restorative proctocolectomy with ileo-anal anastomosis for colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2011. 13:431–437.

ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download