Abstract

Delayed rupture of post-traumatic pseudoaneurysms of the visceral arteries, especially the pancreaticoduodenal artery, is uncommon. Here, we describe a 55-year-old man hemorrhaging from a pseudoaneurysm of the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (IPDA). Computed tomography of the abdomen showed active bleeding in the IPDA and large amounts of hemoperitoneum and hemoretroperitoneum. Selective mesenteric angiography showed that the pseudoaneurysm arose from the IPDA, and treatment by angioembolization failed because the involved artery was too tortuous to fit with a catheter. Damage control surgery with surgical ligation and pad packing was successfully performed. The patient had an uncomplicated postoperative course and was discharged 19 days after the operation. To our knowledge, this is the first report of ruptured pseudoaneurysm of an IPDA after blunt abdominal trauma from Korea.

True and pseudoaneurysms of the visceral arteries are uncommon, accounting for 0.1 to 0.2% of all vascular aneurysms. Visceral pseudoaneurysms may be developed as a complication to blunt abdominal trauma. The arteries mainly involved including the splenic artery, hepatic artery, and renal artery [1]. Visceral artery aneurysms should be treated because of their propensity to rupture and their associated high rates of mortality. Reports regarding ruptured aneurysms of the pancreaticoduodenal artery are extremely rare, especially after abdominal trauma, and few cases have been reported to date [2,3]. Here, we present a case of ruptured pseudoaneurysm of the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (IPDA) after abdominal blunt trauma.

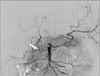

A 55-year-old man presented to the emergency department for investigation of abdominal pain following abdominal trauma 1 month previously. On presentation, he had progressive epigastric pain, which became more severe over a period of two days. He had a laparotomy 20 years ago for appendicitis. He did not have a history of acute or chronic pancreatitis. The patient was receiving medication for high blood pressure and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen showed a pseudoaneurysm of the IPDA from the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) (Fig. 1) and large amounts of hemoperitoneum and hemoretroperitoneum. The results of liver function tests and amylase test were within normal limits. Selective mesenteric angiography was performed. Angiography through the celiac axis showed no active extravasation from the gastroduodenal artery. Selective SMA angiography revealed a pseudoaneurysm and active extravasation of contrast material from the IPDA (Fig. 2). Transcatheter arterial embolization was attempted, but we could not select the extravasated branch because it was tortuous and slender. Initial hemoglobin level was 11.9 g/dL and decreased to 9.8 g/dL 7 hours later, after angiography. Blood pressure was 70/40 mmHg and body temperature was 36.0℃. Laboratory findings showed lactate 2.3 mmol/L (normal range, 0.7 to 2.2), fibrinogen 80.7 mg/dL (normal range, 180 to 350), fibrinogen degradation product 99.5 mg/mL (normal range, 0 to 5), D-dimer 2.73 mg/L (normal range, 0 to 0.3), prothrombin time 1.40 international normalized ratio, activated partial thromboplastin time 51.2 seconds (normal range, 26.5 to 41), antithrombin III 15.5 (normal range, 19 to 31), platelet 63 × 103/mm3 (normal range, 130 to 450). Acidosis was not seen on arterial blood gas. The patient was brought to the operating room, and operative findings showed about 2 L of fresh blood in abdominal cavity and severe diffuse woozing from the retroperitoneum. We approached the lesion near the head of pancreas using the Kocher maneuver. Damage control surgery with blind surgical ligation on suspicious lesion and pad packing was performed. Eight units of packed red blood cells (PRBC) were transfused in the operating room. After operation, blood pressure was stabilized and hemodynamic drug was not needed. Pad was removed 3 days later and there was no active bleeding or diffuse woozing. And laboratory findings were improved well. Patient was stayed in the intensive care unit for 10 days and ventilator management was needed for 7 days. The patient showed good recovery and was discharged 19 days after the operation.

A pseudoaneurysm is a localized arterial disruption of the intimal and medial layers, which is lined with adventitia or perivascular tissue. There are many possible causes of visceral artery pseudoaneurysm, such as pancreatitis, blunt or penetrating abdominal trauma, anastomotic pseudoaneurysm, percutaneous intervention of the biliary tract, arterial dissection, infectious diseases, etc [4].

Visceral artery aneurysms most commonly affect the splenic (60%), proper hepatic (20%), and superior mesenteric (5.5%) arteries. It is important to recognize visceral artery aneurysms because up to 25% of these lesions may be complicated by rupture, and the mortality rate after rupture ranges from 25 to 70% [4]. Aneurysms of the pancreaticoduodenal artery are rare, accounting for <2% of all visceral aneurysms [3].

Delayed traumatic pseudoaneurysm of a visceral artery secondary to abdominal trauma is extremely rare [5,6]. Furthermore, only a few cases of blunt abdominal traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the IPDA have been reported to date [7].

Most visceral artery aneurysms are asymptomatic and are detected incidentally on imaging studies. The diagnosis is not often considered in patients with abdominal pain, thus delaying treatment of symptomatic aneurysms [4]. Symptomatic aneurysms present with abdominal pain or bleeding, which may be intraabdominal or gastrointestinal. Hemorrhage from visceral artery pseudoaneurysms after blunt abdominal trauma is a rare but life-threatening complication. In this case, the initial hemoglobin level was 11.9 g/dL, which decreased to 9.8 g/dL 7 hours after angiography.

CT is useful for detecting small aneurysms and assessing anatomical details. Angiography localizes and defines the size of the aneurysm, and provides the advantage of therapeutic intervention [4]. In the present case, abdominal CT showed a pseudoaneurysm of the IPDA from the SMA and large amounts of hemoperitoneum and hemoretroperitoneum. Furthermore, selective angiography revealed a pseudoaneurysm and active extravasation of contrast material from the IPDA.

The aneurysms can be treated through endovascular techniques or by surgery [8]. Treatment depends on the presentation, location, and size of the aneurysm. A ruptured aneurysm is managed by resection with or without vascular reconstruction, or by transcatheter embolization. Surgical ligation is another treatment option in cases of ruptured aneurysm. Endovascular treatment is safe and feasible in selected patients, but incomplete exclusion may occur, requiring late surgical conversion in a significant number of patients [1].

There is no established cutoff for treatment of pancreaticoduodenal aneurysms, with many experts considering treatment of all such aneurysms by either surgical ligation or endovascular exclusion. Embolization was recommended for patients with pseudoaneurysms originating from branches of the SMA, such as IPDA pseudoaneurysms. Endovascular embolization may stop bleeding immediately, but it is often difficult and fails because the involved artery is too tortuous and slender to select with a catheter. Surgical treatment of visceral artery pseudoaneurysm is usually associated with a high mortality rate; Ding et al. [8] reported an operative mortality rate of 42.9%. Repair of the involved arteries was difficult because of friability of the arterial wall [8]. In this case, repair of the involved arteries was difficult because of friability of the arterial wall and diffuse bleeding. Therefore, damage control surgery with hemostasis by surgical ligation of the involved arteries and pad packing was performed. Damage control surgery is defined as rapid termination of an operation after control of life-threatening bleeding and contamination followed by correction of physiologic abnormalities and definitive management [9]. In this case, we performed damage control surgery due to severe diffuse woozing from the retriperitoneum. Eight units of PRBC were transfused in the operating room. Pad was removed 3 days later and there was no active bleeding or diffuse woozing.

Kim et al. [10] reported a case of delayed gastrointestinal bleeding from traumatic SMA pseudoaneurysm. But to our knowledge, this is the first report of ruptured pseudoaneurysm of an IPDA after blunt abdominal trauma from South Korea.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Marone EM, Mascia D, Kahlberg A, Brioschi C, Tshomba Y, Chiesa R. Is open repair still the gold standard in visceral artery aneurysm management? Ann Vasc Surg. 2011. 25:936–946.

2. Pulli R, Dorigo W, Troisi N, Pratesi G, Innocenti AA, Pratesi C. Surgical treatment of visceral artery aneurysms: a 25-year experience. J Vasc Surg. 2008. 48:334–342.

3. Teng W, Sarfati MR, Mueller MT, Kraiss LW. A ruptured pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm repaired by combined endovascular and open techniques. Ann Vasc Surg. 2006. 20:792–795.

4. Pasha SF, Gloviczki P, Stanson AW, Kamath PS. Splanchnic artery aneurysms. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007. 82:472–479.

5. Lindner T, Bail H, Heise M, Schmidt SC, Jacob D, Haas NP, et al. Traumatic aneurysm of the superior mesenteric artery associated with a burst-fracture of the second lumbar spine: unforeseen sequelae of a fall from a ladder! Unfallchirurg. 2006. 109:160–164.

6. Fitoz S, Atasoy C, Dusunceli E, Yagmurlu A, Erden A, Akyar S. Post-traumatic intrasplenic pseudoaneurysms with delayed rupture: color Doppler sonographic and CT findings. J Clin Ultrasound. 2001. 29:102–104.

7. Leong BD, Chuah JA, Kumar VM, Mazri MY, Zainal AA. Successful endovascular treatment of post-traumatic inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm. Singapore Med J. 2008. 49:e300–e302.

8. Ding X, Zhu J, Zhu M, Li C, Jian W, Jiang J, et al. Therapeutic management of hemorrhage from visceral artery pseudoaneurysms after pancreatic surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011. 15:1417–1425.

9. Schreiber MA. Damage control surgery. Crit Care Clin. 2004. 20:101–118.

10. Kim KS, Chang WY, Lee CH, Choi KM, Her KH. Delayed gastrointestinal bleeding from traumatic superior mesenteric artery pseudoaneurysm. J Korean Surg Soc. 2004. 66:523–525.

ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download