Abstract

Gastric Hodgkin's lymphoma is extremely rare. We present a case of primary Hodgkin's lymphoma arising in the stomach of a 65-year-old woman. The patient complained of epigastric discomfort and reflux for one month. Endoscopic examination revealed a protruding lesion characterized by a smooth surface at the antrum. An abdominal computed tomography uncovered a 2.5 × 2.0 cm, exophytic submucosal mass. After the tentative preoperative diagnosis of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor, a gastric wedge resection was performed. Microscopic examination of the mass demonstrated a diffuse proliferation of large atypical lymphoid cells with mono- and binucleated pleomorphic nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were positive for CD30, CD20, and CD79a, whereas they were negative for cytokeratin, carcinoembryonic antigen, CD3, CD15, epithelial membrane antigen, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1. Based on the morphological features and immunohistochemical results, in addition to the clinical findings, a diagnosis of primary gastric Hodgkin's lymphoma was established.

Non-Hodgkin's B-cell lymphomas represent the vast majority of primary gastric lymphomas [1], whereas primary Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) involving the stomach is exceedingly rare and only a few cases have been reported in the medical literature to date [2-9]. A diagnosis of HL depends primarily on the detection of Reed-Sternberg cells using light microscopy techniques. However, because other malignancies such as anaplastic large cell lymphoma, peripheral T cell lymphoma, and malignant histiocytosis have similar histopathological features or Reed-Sternberg-like cells [4,8], careful differential diagnosis is necessary through the use of immunohistochemistry or gene rearrangement examination. In addition, lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract is more commonly observed in the context of disseminated disease. Therefore, in the case of HL in the stomach, other clinical evaluation is needed to rule out the possibility of secondary tumors occurring as a result of metastasis of systemic Hodgkin's lymphoma. Herein, we report a rare case of primary gastric HL and include a current review of the literature. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case in Korea.

A 65-year old woman was admitted to our hospital because of epigastric discomfort and reflux during the previous month. She reported no significant prior medical history. The initial laboratory test results were unremarkable and there were no abnormal findings on the chest radiographs. Endoscopic examination of the stomach, however, revealed a protruding lesion with a smooth surface at the antrum (Fig. 1), and the abdominal computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 2.5 × 2.0 cm, exophytic submucosal mass with intact overlying gastric mucosa in the greater curvature side of the antrum (Fig. 2) and no evidence of pathologic lymphadenopathy. After the tentative preoperative diagnosis of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor, a laparoscopic gastric wedge resection was performed.

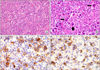

Macroscopically, the resected stomach revealed a 2.5 cm sized ill-defind infiltrative mass, with an intact overlying mucosa throughout the muscle and subserosal layer. Microscopically, the mass showed diffuse infiltration of large atypical lymphoid cells and prominent vascularity in the inflammatory background (Fig. 3A). The large atypical cells had mono- and binucleated pleomorphic nuclei, prominent nucleolus and eosinophilic cytoplasm, which are representative characteristics of Reed-Sternberg cells (Fig. 3B). The inflammatory background consisted of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils and eosinophils.

Upon immunohistochemical ananlysis, the atypical lymphoid cells were positive for CD30 (Fig. 3C), CD20 (Fig. 3D) and CD79a, whereas they were negative for cytokeratin (CK), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), c-kit, CD3, CD15, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), and anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1 (ALK-1). The study of Ebstein-Barr Virus (EBV)-in situ hybridization was also negative. The Warthin-Starry stain for Helicobacter pylori was positive.

To rule out the possibility of secondary invasion of the stomach by systemic Hodgkin's lymphoma, an additional chest CT, neck CT and whole body positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) were performed on the patient. However, there was neither mediastinum nor intrathoracic lymphadenopathy. PET-CT images showed no evidence of abnormal flurodeoxyglucose uptakes in the head, neck, abdomen or pelvis. Based on these morphological, immunohistochemical, and clinical findings, a diagnosis of primary gastric HL was rendered.

The presentation of HL with an extranodal location is quite uncommon [3]. Primary HL involving the gastrointestinal tract is exceedingly rare and has been reported (in descending order) in the stomach, small intestine, large intestines, and esophagus [3,5]. In 1961, Dawson et al. [10] proposed a set of criteria for the diagnosis of primary gastrointestinal HL from secondary involvement because lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract is seen more commonly in the context of disseminated disease. These criteria included 1) absence of peripheral lymphadenopathy at the time of presentation, 2) lack of enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes, 3) normal results for a complete blood count and differential, 4) predominance of the bowel lesion, despite the presence of disease in adjacent lymph nodes, and 5) absence of any lymphomatous involvement of the liver or spleen. Our case fulfilled all of the aforementioned criteria. Based on immunohistochemical results, in addition to those criteria listed above, the frequency of primary gastric HL has been reported as approximately less than 1% of all gastric lymphomas [2].

Histologically, the lymph node architecture of HL is effaced by a variable number of mononuclear Hodgkin's cells and multinucleated Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells admixed with a rich inflammatory background. However, in some cases, careful differential diagnosis through the use of a full panel of immunohistochemical markers is necessary to exclude other disease entities, in which there are similarities with both histopathological features and the presence of HRS-like cells in tumors [4,8]. Phenotypically, the HRS cells were positive for CD30 in nearly all cases, for CD15 in the majority (75 to 85%) of cases and variable expressions of B-cell markers such as CD20 and CD79a [4,8]. In addition, these cells are negative for EMA, T-cell markers and ALK-1. Morphologically, our case can be differentiated from anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), undifferentiated carcinoma, and the anaplastic variant of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Since our patient demonstrated CK-negative, CEA-negative and diffuse CD30-positive with the immunohistochemical staining results, we easily excluded the diagnosis of undifferentiated carcinoma and the anaplastic variant of DLBCL. We eliminated the possible diagnosis of ALCL, since the CD15 status of HRS cells was different in our case from that observed in previous reports [3,7,8]. However, we finally diagnosed our case as HL of the stomach, because EMA and ALK-1 were negative, and B-cell markers, such as CD20 and CD79a, were positive, which was in accordance with results from a previous report [4].

The epidermiologic and pathogenic association of HL with the EBV has been established even though its presence is not diagnostic of HL [8]. However, EBV infection was not present in the pathologic portion of the stomach analyzed in our case. Regarding cases of HL located at unusual sites, such as gastric HL, some authors have suggested that the gastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type, which is similar to DLBCL, may be a precursor lesion for CHL [9]. The results of tests for H. pylori were positive in our case; however, none of our findings suggested the presence of gastric MALT lymphoma. Therefore, the pathogenesis of our case is not clear because the EBV infection was not proven and the absence of gastric MALT lymphoma.

The prognosis of gastric HL is poor with 45 to 60% of patients dying within the first year of diagnosis [4,8]. Therefore gastric HL has been treated surgically with postoperative chemo- or radiotherapy [4,8]. Postoperative therapy may be necessary because gastric HL may represent only one expression of systemic lymphoma, and another portion of the lymphatic system may develop malignancy postoperatively. Our patient underwent laparoscopic gastric wedge resection and then received six cycles of adriamycin-vincristine-doxorubicin chemotherapy, as a precautionary measure. No recurrent disease was observed after four months of follow-up.

In conclusion, when we encounter a case involving anaplastic tumors of the stomach, we must be aware of the existence of gastric HL in spite of its rarity and make a precise diagnosis on the basis of histological findings and essential immunohistochemical analyses.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Endoscopic examination of the stomach reveals a protruding lesion with smooth surface at the antrum. |

| Fig. 3Histologic and immunohistochemical features of the gastric tumor. (A) The tumor shows diffuse infiltration of large atypical cells and prominent vascularity in the inflammatory background (H&E, ×100). (B) Mononuclear Hodgkin cells (thick arrow) and binucleated Reed-Sternberg cells (thin arrow) are seen (H&E, ×400). (C) Hodgkin cells are positive for CD30. The membranous and paranuclear (Golgi) pattern is typical (immunostain, ×400). (D) Some Hodgkin cells for CD20 are positive (immunostain, ×400). |

References

1. Min HR, Shin YM, Lee SD, Chun BK. Clinical study of primary gastric lymphoma and analysis of prognostic factors. J Korean Surg Soc. 1999. 56:906–914.

2. Colucci G, Giotta F, Maiello E, Fucci L, Caruso ML. Primary Hodgkin's disease of the stomach: a case report. Tumori. 1992. 78:280–282.

3. Devaney K, Jaffe ES. The surgical pathology of gastrointestinal Hodgkin's disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1991. 95:794–801.

4. Ogawa Y, Chung YS, Nakata B, Muguruma K, Fujimoto Y, Yoshikawa K, et al. A case of primary Hodgkin's disease of the stomach. J Gastroenterol. 1995. 30:103–107.

5. Mori N, Yatabe Y, Narita M, Hayakawa S, Ishido T, Kikuchi M, et al. Primary gastric Hodgkin's disease. Morphologic, immunohistochemical, and immunogenetic analyses. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995. 119:163–166.

6. Doweiko J, Dezube BJ, Pantanowitz L. Unusual sites of Hodgkins lymphoma: CASE 1. HIV-associated Hodgkin's lymphoma of the stomach. J Clin Oncol. 2004. 22:4227–4228.

7. Venizelos I, Tamiolakis D, Bolioti S, Nikolaidou S, Lambropoulou M, Alexiadis G, et al. Primary gastric Hodgkin's lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005. 46:147–150.

8. Hossain FS, Koak Y, Khan FH. Primary gastric Hodgkin's lymphoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2007. 5:119.

9. Saito M, Tanaka S, Mori A, Toyoshima N, Irie T, Morioka M. Primary gastric Hodgkin's lymphoma expressing a B-Cell profile including Oct-2 and Bob-1 proteins. Int J Hematol. 2007. 85:421–425.

10. Dawson IM, Cornes JS, Morson BC. Primary malignant lymphoid tumours of the intestinal tract. Report of 37 cases with a study of factors influencing prognosis. Br J Surg. 1961. 49:80–89.

ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download