Abstract

Inflammatory myofibroblastic (IMF) tumor is a rare solid tumor that often affects children. IMF tumors occur primarily in the lung, but the tumor may affect any organ system with protean manifestations. A 22-year-old woman was evaluated for palpable low abdominal mass that had been increasing in size since two months prior. Abdominal computed tomography showed a lobulated, heterogeneous contrast enhancing soft tissue mass, 6.5 × 5.7 cm in size in the ileal mesentery. At surgery, the mass originated from the greater omentum laying in the pelvic cavity and was completely excised without tumor spillage. Histologically, the mass was a spindle cell lesion with severe atypism and some mitosis. Immunohistochemistry for anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1 revealed that the lesion was an IMF tumor. Because of its local invasiveness and its tendency to recur, this tumor can be confused with a soft tissue sarcoma. Increasing physician awareness of this entity should facilitate recognition of its clinical characteristics and laboratory findings.

Inflammatory myofibroblastic (IMF) tumor is a rare solid tumor that often affects children. The variate of terms used to describe this entity includes inflammatory pseudotumor, cellular inflammatory pseudotumor, plasma cell granuloma, inflammatory myofibrohistiocytic tumor, and more recently, inflammatory fibrosarcoma. This lesion consists of inflammatory cells and myofibroblastic spindle cells [1,2]. Although children constitute the majority of the reported cases of IMF tumor, this disease rarely appears in the adult. IMF tumors occur primarily in the lung and upper respiratory tract, but the tumor may affect any organ system with protean manifestations [3]. In adults, it is known to be mostly located in the lungs. In children, urinary or gastrointestinal IMF tumors have been reported to be twice as numerous as pulmonary IMF tumors [4,5].

IMF tumors in abdomen have clinical importance because the lesions often mimic malignant neoplasms, such as sarcomas, lymphomas, or metastases. Although its histopathologic nature is benign, it is not easy to differentiate from a malignant tumor because of its local invasiveness and its tendency to recur [3]. Additionally, recent reports concerning the malignant transformation of IMT and lymphoreticular malignancy arising in the residual IMF tumor necessitate careful review of this entity [1,6].

We present a case of IMF tumor originated from the greater omentum, which was thought to be gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) originated from mesentery preoperatively but was found to be otherwise on histopathology.

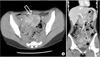

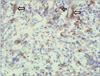

A 22-year-old woman was evaluated for palpable low abdominal mass which had been increased in size since two months ago. She denied any gastrointestinal symptoms other than palpable mass, and any gynecologic symptoms including vaginal discharge or bleeding. Physical examination revealed man's fist sized round and movable mass without tenderness around the mass. Vital signs including blood pressure, pulse rate, body temperature, and respiration were stable. She had no abnormal laboratory findings. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a lobulated and heterogeneous contrast enhancing soft tissue mass with 6.5 × 5.7 cm size in the ileal mesentery (Fig. 1). She underwent open laparotomy with 8 cm sized low midline skin incision for mass excision. At surgery, a 7 cm sized mass originated from the greater omentum was found in pelvic cavity. The feeding vessels of the mass were ligated and the mass was removed without tumor spillage or capsular injury (Fig. 2). Histologically, the resected mass was spindle cell lesion with moderate to severe atypism, some mitosis and surrounding inflammatory cells infiltration (Figs. 3, 4). Additional immunohistochemistry with anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-1 revealed that the lesion was IMF tumor (Fig. 5). She was discharged on postoperative day 3 without any complication. CT scan which was performed at six months after surgery revealed no local tumor recurrence or intra-abdominal metastasis. She has remained very well without any symptoms during the six months since discharge.

IMF tumors have a predilection for children and young adults, with a mean age of ten years at presentation and girls are slightly more commonly affected [7]. IMF tumor is a rare spindle-cell lesion of intermediate malignant potential [8], occurring in both pulmonary and extra-pulmonary tissues. IMF tumors in the abdomen are a rare entity, and if found they arise in any sites of abdominal organs. Primary omental tumors are very rare and IMF tumor of the omentum is even more uncommon. A majority of these are leiomyosarcomas, leiomyomas and GISTs reported in the 5th and 6th decade of life [9].

The cause of IMF tumors is unclear; many authors have postulated a postinflammatory process. Evidence to support a directly infectious etiology is scanty, but an immunological response to an infectious agent or noninfectious agent remains possible [5,8,9]. Whereas some reporters demonstrated that IMF tumors are true neoplasms and some believe the IMF tumors to be a low-grade sarcoma with inflammatory cells as it has a potential for local infiltration, recurrence, multicentricity, and rarely metastases. Also, ALK positivity is detected in 36 to 60% of cases, and is associated with cytogenetic abnormalities involving the ALK gene on chromosome 2. The presence of chromosomal aberrations (30 to 40% of cases) in these tumors suggests that IMT is a neoplastic proliferation of clonal origin [8]. In our case, there was no evidence of infection or inflammatory response and no history of trauma in her abdomen. The tumor was single, well circumscribed, and movable. The immunohistochemical staining result for ALK-1 shows strong positivity of tumor cytoplasm. Considering most aspects of this tumor, we think that it was not the mass by postinflammatory process, but genuine tumor.

Most IMF tumors had been considered as benign lesion. Nevertheless, the clinical, radiological and histological features of these may cause confusion with malignant lesions. IMF tumors from the mesentery or omentum would be found as a large mass mimicked a sarcoma, lymphoma, or carcinoma. Also, mesenteric or omental IMF tumors appeared as well defined solid, mixed-echogenic masses in sonography and prominent vascularity on Doppler sonography. On CT scans, these tumors shows typically heterogenous attenuating enhancement [2]. In our case, the tumor was a lobulated and heterogeneous mass with contrast enhancement originated from mesentery on CT scan. However, with these findings, definite radiologic differentiation of an IMF tumor from other malignancies may be impossible. Imaging studies may be helpful not for differentiation between benign and malignant lesion, but for the decision whether complete resection can be possible. The diagnosis of IMF tumor should be established with certainty only on pathological examination.

The natural history may range from spontaneous regression through gradual enlargement to rapid growth with local invasion. Complete surgical resection is the treatment of choice although spontaneous resolution has been reported. Additional treatments including radiotherapy or chemotherapy are not indicated. There are occasional reports of successful resolution of these tumors with steroids, radiotherapy, chemotherapy or even nonsteroidal inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen. However, there is no expert consensus that NSAIDs have a therapeutic effect on the course of IMF tumor, so this remains currently as a "surgical disease." Only conservative surgery may suffice. For recurrent or metastatic tumor, reexcision or metastasectomy is enough to treat their lesions [7-10].

Microscopically the IMF tumor consists of spindle shaped cells that are mixed with a chronic inflammatory component that consists of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and occasional histiocytes. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies have shown that the spindle cells are myofibroblasts. Immunohistochemistry for ALK is relatively specific for IMF tumor among the spectrum of fibroblastic-myofibroblastic tumors and other potential mesenchymal mimics of IMF tumor. Cellular atypia, ganglion-like cells, aneuploidy, ALK reactivity and p53 overexpression might be associated with more aggressive clinical behavior [10]. In our case, the mass was spindle cell lesion with severe atypism and some mitosis. As shown in Figs 4 and 5, ganglion-like cells were present and the immunohistochemistry result for ALK-1 shows strong positivity of tumor cytoplasm. Based on these findings, her tumor may be very aggressive, with local spread, and recur after successful resection. Therefore, a careful follow-up is required.

In summary, because of its local invasiveness and its tendency to recur, IMF tumor can be confused with malignant lesions. Because the treatment of IMF tumor is conservative surgery, preoperative recognition is important to avoid radical surgical resection, radiation therapy, and intensive multi-agent chemotherapy that would be appropriate treatments for soft tissue sarcomas. Increasing physician awareness of this entity would facilitate recognition of its characteristic clinical and laboratory findings. Also, because the tumor with cellular atypia, ganglion-like cells, and ALK reactivity has a more aggressive clinical behavior, a careful follow-up is required.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan of the abdomen in axial (A) and coronal (B). A lobulated and heterogeneous contrast enhancing soft tissue mass (arrow) originating from the ileal mesentery is seen.

Fig. 2

Specimen consists of a portion of tan-colored tissue, measuring 7.5 × 7.0 × 5.0 cm. Arrow indicates feeding vessel originated from greater omentum.

References

1. Coffin CM, Watterson J, Priest JR, Dehner LP. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 84 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995. 19:859–872.

2. Kim SJ, Kim WS, Cheon JE, Shin SM, Youn BJ, Kim IO, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors of the abdomen as mimickers of malignancy: imaging features in nine children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009. 193:1419–1424.

3. Stringer MD, Ramani P, Yeung CK, Capps SN, Kiely EM, Spitz L. Abdominal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours in children. Br J Surg. 1992. 79:1357–1360.

4. Mergan F, Jaubert F, Sauvat F, Hartmann O, Lortat-Jacob S, Revillon Y, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in children: clinical review with anaplastic lymphoma kinase, Epstein-Barr virus, and human herpesvirus 8 detection analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2005. 40:1581–1586.

5. Sawant S, Kasturi L, Amin A. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Indian J Pediatr. 2002. 69:1001–1002.

6. Pecorella I, Ciardi A, Memeo L, Trombetta G, de Quarto A, de Simone P, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumour of the liver: evidence for malignant transformation. Pathol Res Pract. 1999. 195:115–120.

7. Sodhi KS, Virmani V, Bal A, Saxena AK, Samujh R, Khandelwa N. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the omentum. Indian J Pediatr. 2010. 77:687–688.

8. Saleem MI, Ben-Hamida MA, Barrett AM, Bunn SK, Huntley L, Wood KM, et al. Lower abdominal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor -an unusual presentation- a case report and brief literature review. Eur J Pediatr. 2007. 166:679–683.

9. Gupta CR, Mohta A, Khurana N, Paik S. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the omentum: an uncommon pediatric tumor. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009. 52:219–221.

10. Coffin CM, Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: comparison of clinicopathologic, histologic, and immunohistochemical features including ALK expression in atypical and aggressive cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007. 31:509–520.

ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download