Abstract

Purpose

Single port laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SPLC) is a new advanced technique in laparoscopic surgery. Many laparoscopic surgeons seek to gain skill in this new technique. However, little data has been accumulated and published formally yet. This article reports the achievement of 100 cases of SPLC with the hopes it will encourage laparoscopic surgery centers in the early adoption of SPLC.

Methods

A retrospective review of 100 prospectively selected cases of SPLC was carried out. All patients had received elective SPLC by a single surgeon in our center from May 2009 to December 2010. Our review suggests patients' character, perioperative data and postoperative outcomes.

Results

Forty-two men and 58 women with an average age of 45.8 years had received SPLC. Their mean body mass index (BMI) was 23.85 kg/m2. The mean operating time took 76.75 minutes. However, operating time was decreased according to the increase of experience of SPLC cases. Twenty-one cases were converted to multi-port surgery. BMI, age, previous low abdominal surgical history did not seem to affect conversion to multi-port surgery. No cases were converted to open surgery. Mean duration of hospital stay was 2.18 days. Six patients had experienced complications from which they had recovered after conservative treatment.

Conclusion

SPLC is a safe and practicable technique. The operating time is moderate and can be reduced with the surgeon's experience. At first, strict criteria was indicated for SPLC, however, with surgical experience, the criteria and area of SPLC can be broadened. SPLC is occupying a greater domain of conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been established as the first choice treatment of benign gall bladder disease needing removal of gall bladder (GB) in general surgery [1]. It shortened the operation time and duration of hospital stay, reduced post operative pain [2] and made better recovery compared with conventional open cholecystectomy [3,4]. At first laparoscopic cholecystectomy began with four-port surgery [5]. But now, many centers do three-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The concept of single port laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SPLC) arose from the idea of the "fewer-port" cholecystectomy [6].

Multiple ports were good for surgeons to handle laparoscopic instruments and to imagine and understand intra-abdominal structure anatomically [7]. The more ports that were used, however, the higher rate of complications that occurred; bleeding on port insertion site, post operative pain, decrease of cosmetic effect, organ injury that might be caused by inserting the trocar, and incisional hernia [8].

Single-port access surgery was the natural evolution of this reduced port concept for cholecystectomy [9,10]. The more surgical skills became sophisticated, the less patients wanted anatomical changes [11]. SPLC reflects the trend of minimally invasive surgery. Safety is the most important concern of all in new operative techniques [12].

The transumbilical cholecystectomy was first described in 1999 [13,14]. However, SPLC is still in its early days with little data having been accumulated and published, formally [15]. At our center, single port laparoscopic surgery has just reached the 100th surgery mark in December, 2010. The first operation was done in May, 2009. This article reports on the achievement of 100 cases of SPLC in the hopes it will encourage laparoscopic surgery centers that are beginning SPLC.

From May 2009 to December 2010, 100 patients who had GB stone with or without cholecystitis, or GB polyp had undergone elective SPLC by a single surgeon. The diagnosis of GB stone or GB polyp was based on abdominal ultrasonography (US) or computed tomography (CT). Only one case used magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography CT to rule out malignancy. Some patients had subjective symptoms such as right upper quadrant abdominal pain, dyspepsia, or abdominal discomfort. SPLC was done under the patients' informed consent: information about the surgical procedure, the difference in cost between SPLC and conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy was provided.

In the very beginning, we selected GB stone cases without any evidence of inflammation based on radiologic findings and patients' symptoms. After 10 cases, patients who experienced right upper quadrant abdominal pain were also enrolled. They were diagnosed as cholecystitis due to GB stone which meant GB stone caused inflammatory change of the GB, supported by radiologic findings such as wall thickening of GB. The other inclusion criteria was GB polyp over 8 mm in size. Most cases of GB polyp were found incidentally through regular health care screening tests. If the size of the GB polyp was less than 10 mm, surgery was performed only when the patient wanted to receive surgical treatment.

For the first 20 cases, patients with a body mass index (BMI) over 25 kg/m2 were excluded, but after the 20 cases BMI was not used as the exclusion criteria. Among one hundred patients, no one had previously received upper abdominal surgery.

All 100 patients were admitted the day before the operation and received elective SPLC under general anesthesia.

The surgical technique has been evolving. Two different positions were used for the series of operations. In the first 70 cases, patients were laid in the lithotomy position. The operator stood in the space between patients' legs. The first assistant who played the role of scopist stood at the patient's left side and the second assistant was positioned on the right side of the scopist. The scrub nurse stood on the right side of the patient. Two monitors were put on the both sides of patients' shoulders. In the later 30 cases, patients were laid in the supine position. All surgeons stood on the left side of the patient. The operator, the first assistant, and the second assistant stood in order from foot to head.

A 2.5 cm transumbilical vertical incision was made. Linea alba and peritoneum was opened with electrocautery. For the first 35 cases, Alexis Wound Retractor (Applied Medical Resources Co., Rancho Santa Margarita, CA, USA) and surgical glove were used for the single cannel. For the following 65 cases, multi-channel trocar, Octo port (dalimSurgNET, Seoul, Korea) or Glove port (NELIS, Bucheon, Korea) was used to make the cannel.

The laparoscopic camera was inserted through the central passage. Flexible 10 mm diameter 0° angled laparoscope with standard length or rigid 30° angled laparoscope of 10 mm or 5 mm diameter with standard length was used. The surgeon was more accustomed to single port surgery when straight instruments were used. Flexible instruments were used for only the first 30 cases. After the 30 cases, all the instruments were the same as those of conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy including 30° angled rigid laparoscope of 5 mm diameter. Only flexible hook Bovie (Cambridge Hook, Cambridge Endoscopic Device Inc., Framingham, MA, USA) was needed additionally.

Cystic duct and artery were dissected using laparoscopic rigid dissector. 10 mm Hemo-O-Lok clip made with prolene material was used for ligating cystic duct. Each proximal and distal end of cystic duct were clipped. Cystic artery was ligated with 5 mm Hemo-O-Lok clip, then sheared with laparoscopic scissors. GB was retracted in the cephalic direction then separated from the liver bed. GB was pulled out through the port site directly. Peritoneum and fascia were sutured and the subcutaneous tissue was sutured. No skin suture was needed after skin edges were approximated. Only vertical incision was visible and no stitches were found [16].

Continuous data were expressed as mean (standard deviation, SD) and compared using the Student's t-test. A P-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad InStat ver. 3.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

This article demonstrates disease indication, mean operating time (mean, range, SD), conversion rate to multi-port surgery, rate of intraoperative bile leakage, rates of postoperative complications, and mean hospital day. The operating time was defined in minutes from first incision to final closure. The observed differences were subjected to statistical analysis using Student's t-test: differences were considered significant for P-value < 0.05.

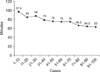

From May 2009 to December 2010, 100 cases of SPLC were performed by a single surgeon. Table 1 shows us patient characteristics including age, gender, BMI, previous history of abdominal surgery, diagnostic tools, patients' symptom and diagnoses. Forty-two men and 58 women aged an average of 45.8 years (range, 27 to 68 years) received SPLC. Their mean BMI was 23.85 kg/m2 (range, 18.4 to 33.7 kg/m2). The BMI of 22 patients were over than 25 kg/m2. Mean operating time took 76.75 minutes (range, 45 to 125 minutes). However, operating time decreased according to the increase of experience of single port surgery cases. Fig. 1 explains operating time saved according to the surgeon's experiences [17]. Twenty-one patients had had a history of previous surgery. Nine underwent appendectomy, 13 had obstetric and gynecologic surgery, and 2 had urology surgery. Sixty-seven patients had no symptom, 27 patients had abdominal pain and 6 had gastric discomfort. Forty-nine patients were diagnosed with GB stone, 32 of them were symptomatic cholecystitis with GB stone. Fifty patients were diagnosed with GB polyp, and 1 was GB empyema. Twenty-four of the 50 patients diagnosed with GB polyp, were pathologically diagnosed with cholesterol polyp and the other 26 were tubular adenoma. CT and US were used for the diagnoses. Eighteen cases had intra-operative bile leakage because GB were injured when dissected from the liver bed; 10 cases were cholecystitis and 8 were GB polyp. No postoperative bile leakage occurred. Eighty-four patients were discharged two days after operation.

There were 6 patients with complications after surgery described in Table 2. One patient experienced liver enzyme elevation; it resolved spontaneously. Three had wound infection with fever. Wound dressing and antibiotics resolved these, and their wounds were found clean at out patient clinic. One patient suffered continuous abdominal pain after surgery. Sludges in the common bile duct were found on abdominal US and he received endoscopic sphincterotomy. No incisional hernia was observed.

Of the one hundred cases of SPLC, 21 cases were converted to multi-port surgery. Seven cases were converted to three-port surgery, and 14 cases were converted to two-port surgery. The main reason for conversion to multi-port surgery was poor visualization of Calot's triangle [18]. Three cases were converted because of bleeding. We tried to understand the reason of conversion to multi-port surgery and compared variable parameters of the pure single port surgery and converted to multi-port surgery. In Table 3, we compared age, gender, BMI and previous abdominal surgery history. Interestingly, each parameter did not have significant statistical meaning. No conversions were performed due to complications, and no conversions resulted in complications. There was no case of conversion to open surgery.

Even though the first transumbilical cholecystectomy was described in 1999 [14], SPLC is still in its early days [19]. SPLC is challenging to laparoscopic surgeons [20], however, there are a few reports of laparoscopic single port surgery. When a new technique is accepted, many factors should be considered. Who is a likely candidate for SPLC? Is it a safe method without severe complications? Is it a difficult method for a surgeon to become accustomed to? Does it increase operation time? Does the new technique need new surgical instruments and will it increase the cost of equipment? This review of 100 cases of SPLC aims to answer those questions.

For the 10 cases at the very beginning of our study, we restricted indication on only simple GB stone without any symptom or any evidence of inflammatory change on image study. After the 10 cases, the strict criteria were reduced as the surgeon became accustomed to the new method. For the first 20 cases, BMI over 25 kg/m2 were excluded. However, BMI did not have much influence on conversion to multi-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Twenty-one cases were converted to multi-port surgery. We compared data of the single port laparoscopic surgery with converted multi-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Mean BMI didn't seem to have statistically significant meaning (P = 0.381).

SPLC did not incur severe complications. Liver enzyme elevation and delayed bleeding resolved spontaneously. Wound infection was controlled by wound dressing and antibiotics. Song et al. [21] stated the risks associated with SPLC were not greater than multi-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Han et al. [22] demonstrated that SPLC could be applied effectively and performed as quickly as conventional cholecystectomy with a learning curve of approximately 8 cases. We found that mean operation time dropped dramatically after thirty cases. Youn et al. [17] suggested the learning curve for SPLC for a surgeon with prior conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy experience and for a self taught single port technique should be around 30 cases. The time decreasing slope was rigid for the first 30 cases. After that the slope remained flat. The more expert to the surgical skill, the more difficult cases were enrolled. Thus, operation time does not sharply decrease.

At first, flexible laparoscopic instruments were used. After 10 cases, all the conventional rigid laparoscopic instruments were used for SPLC. A hook Bovie was the only flexible instrument. If any laparoscopic center is considering trying SPLC, little extra cost of equipment is needed because conventional equipment would suffice in SPLC as well.

This report is based on the results of only one surgeon. The results from several surgeon groups are required to broaden the results. We only mentioned the short-term postoperative data excluding long-term postoperative data. For example, long-term cosmetic effect [23-25], incidence of incisional hernia after single port lapa-cholecystectomy, subjective patientpain [26-28] or patient satisfaction might be valuable data. SPLC superiority would be more strongly supported if a comparison with conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy had been suggested. Surgical history, however, didn't seem to influence SPLC. No patient had upper abdominal surgical history such as stomach operation or liver operation. The challenge of those types of cases might require new methods or instruments.

In conclusion, SPLC is a safe and practicable technique. The operating time is moderate and can be reduced with the surgeon's experience. About 30 cases should be the learning curve for a surgeon to become accustomed to SPLC. At first, strict criteria was indicated for SPLC. However, the surgical experience can reduce the criteria and broaden the spectrum of SPLC. To set up SPLC in a surgery center, little extra cost is needed because conventional laparoscopic equipment is useful in SPLC. SPLC is occupying a greater domain of conventional laparosopic cholecystectomy.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Operating time and learning curve. The learning curve for single port laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be around 30 cases. The time decreasing slope was stiff for the early 30 cases. After that the slope became flat, because more difficult cases were enrolled.

References

1. Gallstones and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. NIH Consens Statement. 1992. 10:1–28.

2. Buunen M, Gholghesaei M, Veldkamp R, Meijer DW, Bonjer HJ, Bouvy ND. Stress response to laparoscopic surgery: a review. Surg Endosc. 2004. 18:1022–1028.

3. Glaser F, Sannwald GA, Buhr HJ, Kuntz C, Mayer H, Klee F, et al. General stress response to conventional and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 1995. 221:372–380.

4. Keus F, Gooszen HG, Van Laarhoven CJ. Systematic review: open, small-incision or laparoscopic cholecystectomy for symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009. 29:359–378.

5. Trichak S. Three-port vs standard four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2003. 17:1434–1436.

6. Cuschieri A. Laparoscopic surgery: current status, issues and future developments. Surgeon. 2005. 3:125–130. 132–133. 135–138.

7. Sodergren MH, Orihuela-Espina F, Froghi F, Clark J, Teare J, Yang GZ, et al. Value of orientation training in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2011. 98:1437–1445.

8. Kaushik R. Bleeding complications in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: incidence, mechanisms, prevention and management. J Minim Access Surg. 2010. 6:59–65.

9. Leggett PL, Churchman-Winn R, Miller G. Minimizing ports to improve laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2000. 14:32–36.

10. Nagy AG, Poulin EC, Girotti MJ, Litwin DE, Mamazza J. History of laparoscopic surgery. Can J Surg. 1992. 35:271–274.

11. Cuschieri A. Minimal access surgery: the birth of a new era. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1990. 35:345–347.

12. Kojima Y, Tomiki Y, Sakamoto K. Our ideas for introduction of single-port surgery. J Minim Access Surg. 2011. 7:109–111.

13. Bresadola F, Pasqualucci A, Donini A, Chiarandini P, Anania G, Terrosu G, et al. Elective transumbilical compared with standard laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Eur J Surg. 1999. 165:29–34.

14. Piskun G, Rajpal S. Transumbilical laparoscopic cholecystectomy utilizes no incisions outside the umbilicus. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1999. 9:361–364.

15. Elsey JK, Feliciano DV. Initial experience with single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2010. 210:620–626.

16. Cuesta MA, Berends F, Veenhof AA. The "invisible cholecystectomy": a transumbilical laparoscopic operation without a scar. Surg Endosc. 2008. 22:1211–1213.

17. Youn SH, Roh YH, Choi HJ, Kim YH, Jung GJ, Roh MS. The learning curve for single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy by experienced laparoscopic surgeon. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011. 80:119–124.

18. Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995. 180:101–125.

19. Chow A, Purkayastha S, Aziz O, Paraskeva P. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery for cholecystectomy: an evolving technique. Surg Endosc. 2010. 24:709–714.

20. Ersin S, Firat O, Sozbilen M. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: is it more than a challenge? Surg Endosc. 2010. 24:68–71.

21. Song SC, Ho CY, Kim MJ, Kim WS, You DD, Choi DW, et al. Clinical analysis of single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomies: early experience. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011. 80:43–50.

22. Han HJ, Choi SB, Park MS, Lee JS, Kim WB, Song TJ, et al. Learning curve of single port laparoscopic cholecystectomy determined using the non-linear ordinary least squares method based on a non-linear regression model: an analysis of 150 consecutive patients. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011. 18:510–515.

23. Zhu JF, Hu H, Ma YZ, Xu MZ. Totally transumbilical endoscopic cholecystectomy without visible abdominal scar using improved instruments. Surg Endosc. 2009. 23:1781–1784.

24. Hong TH, You YK, Lee KH. Transumbilical single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: scarless cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2009. 23:1393–1397.

25. Lee SK, You YK, Park JH, Kim HJ, Lee KK, Kim DG. Single-port transumbilical laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a preliminary study in 37 patients with gallbladder disease. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009. 19:495–499.

26. Solomon D, Bell RL, Duffy AJ, Roberts KE. Single-port cholecystectomy: small scar, short learning curve. Surg Endosc. 2010. 24:2954–2957.

27. Kroh M, El-Hayek K, Rosenblatt S, Chand B, Escobar P, Kaouk J, et al. First human surgery with a novel single-port robotic system: cholecystectomy using the da Vinci Single-Site platform. Surg Endosc. 2011. 25:3566–3573.

28. Tsimoyiannis EC, Tsimogiannis KE, Pappas-Gogos G, Farantos C, Benetatos N, Mavridou P, et al. Different pain scores in single transumbilical incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus classic laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2010. 24:1842–1848.

ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download