Abstract

A 53-year-old woman was diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) of the stomach. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a huge mass (12 cm in diameter), likely to invade pancreas and spleen. In the operation field, the tumor was in an unresectable state. The patient was then started on imatinib therapy for 4 months. On follow-up imaging studies, the tumor almost disappeared. We performed total gastrectomy and splenectomy upon which two small-sized residual tumors were found on microscopy. In this paper, we describe a case of clinicopathologic change in unresectable GIST after neoadjuvant imatinib mesylate.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are the most common mesenchymal tumor of the human gastrointestinal tract, which arise from intestinal cells of Cajal [1]. Before the imatinib (Glivec, Novartis Korea, Seoul, Korea) era, surgery was the only therapeutic treatment for GIST. Even after the complete resection of GIST, however, most patients with advanced disease relapsed making the prognosis of patients with metastatic and/or recurrent GIST extremely poor [2].

Although a number of experiences have been reported with imatinib mesylate (IM) in patients with unresectable or metastatic GISTs without operation, there were few reports about neoadjuvant experience in those cases. We report a case of unresectable gastric GIST who underwent neoadjuvant therapy followed by surgical resection.

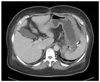

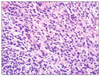

A 53-year-old female was admitted to our department of general surgery because of dyspepsia and vomiting during the previous month. For her past history, she was diagnosed with diabetes and hypertension 10 years prior under medical treatment. There was no significant family history. On abdominal physical examination, there was no significant finding. Laboratory findings were nonspecific. Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) and F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) CT showed an approximately 12 cm sized heterogeneous mass located from fundus to mid body of stomach, which seemed to invade pancreas, spleen and left adrenal gland (Fig. 1A-C). Endoscopic biopsy performed in our institution and pathologic report revealed a spindle cell tumor consistent with GIST (Figs. 2, 3). Results of immunohistochemical stain: the tumor cell was positive for CD34 and c-kit (CD117), weak positive for smooth muscle actin; whereas S-100 was negative (Fig. 4).

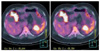

Two weeks later, we performed laparotomy, but the mass was huge and invaded the pancreas and retroperitoneum very tightly so that it couldn't be resected. Ten days after the operation, the patient was started on imatinib therapy, a daily dose of 400 mg, maintained for 4 months. No adverse event occured during imatinib treatment. A follow-up CT, 2 months after the start of imatinib, showed a dramatic reduction in the size of the tumor. And 4 months after follow-up CT, there was no evidence of mass lesion in the stomach (Fig. 5); on the gastroduodenoscopy, the mass lesion was invisible with only an ulcerative lesion observed in the same location (Fig. 6). Although the mass lesion was not revealed clearly at the follow-up imaging study (Fig. 7), we planned operation to achieve curative resection of the tumor. 5 months after the treatment with imatinib, the patient underwent total gastrectomy and splenectomy. The stomach was adhered to the spleen, tightly, and the lesion was found between stomach and spleen, firm and white, having irregular margin. Pathologically, very few tumor cells were in the fibrotic tissue; residual tumor size was 0.3 × 0.2 cm and 0.2 × 0.2 cm, respectively. The tumor consisted of spindle cells with a mitotic activity index of 1/50 HPF on microscopy. Around the residual tumor, hyalinized fibrosis, inflamed granulation tissue, dystrophic calcification, and necrosis and abscess were seen (Fig. 8). After surgery, the patient was discharged without any special complications.

GIST is the most common mesenchymal tumor of the gastrointestinal tract. Up to two-thirds of GISTs show malignant behavior with high recurrence rates [3]. The main treatment of GIST is complete surgical resection. Therefore, improving the rate of complete resection is a key challenge in the treatment of GISTs. Neoadjuvant therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibition has potential usefulness in primary GIST, although not yet as a standard of care [4]. Several retrospective studies suggested that resection of residual lesions could prolong progression-free survival if it is done while the tumors are under control with imatinib [5]. It is also emphasized that imatinib should be continued even after complete resection of all visible disease [6]. However, the role of resection of residual tumors after imatinib therapy has not been established, and several phase III clinical trials to investigate the role of surgical resection in this setting are ongoing or planned worldwide [7].

There is no disagreement on the benefit of treatment with imatinib for malignant GISTs, but the clinical outcome of neoadjuvant treatment with imatinib is not well established [8]. In our case, we could perform complete resection of the GIST by down-sizing of the tumor after treatment with imatinib. The duration of neoadjuvant therapy with imatinib may vary according to response to the treatment, but surgery may be performed after sufficient shrinkage of tumors is observed; typically after 4 to 6 months and within 12 months of imatinib treatment [6]. The standard initial dose of imatinib is 400 mg per day in patients with unresectable or metastatic GISTs. In a randomized phase III trial that compared 400 mg daily with 800 mg daily, the 800 mg daily was a more toxic but not more effective dose [9].

The goal of surgery is complete resection of tumor, possibly avoiding the occurrence of tumor rupture and achieving negative margins [7]. In our case, there was no tumor rupture during the operative procedure and pathologically negative margins were obtained.

Radiographic tumor response to preoperative imatinib correlated significantly with complete resection, with 91% of patients with partial responses achieving complete resection, versus 4% of patients with progressive disease [10].

Radiographic and metabolic complete response based upon FDG-PET are not always concordant with a pathologic complete response; therefore, it should be born in mind that the pathological evaluation on the surgically resected materials obtained from patients treated with IM might be indispensable for the elucidation of the therapeutic effect of IM on GIST [10]. In our case, follow-up PET showed a hypermetabolic lesion around medial side of the spleen; residual tumor was observed in that site on microscopy, but follow-up CT showed no evidence of mass lesion in the stomach. In the surgical findings, the lesion had extensive areas of fibrotic changes and there were severe adhesions between the lesion and spleen, so it was suspected to be invasion, thus we performed total gastrectomy and splenectomy.

This case report has some limitations. First, the patient's follow-up period is short and will not be an accurate prognostic assessment. Second, the first surgery could have been avoided. In the case of lesion suspected to be in an inoperable state, neoadjuvant chemotherapy should take precedence over surgical procedure.

In summary, we report a case of GIST in an unresectable state, initially, who underwent complete surgical resection following imatinib treatment. In cases of advanced GISTs, neoadjuvant treatment with imatinib may provide an opportunity for surgeons to perform a complete resection.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Computed tomography and fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) computed tomography (CT) scans. Images showed a huge heterogeneous mass that is originated from stomach (A) and the tumor seemed to invade pancreas and spleen (B). A FDG-PET CT scan showed FDG uptake in the lesion (C).

Fig. 2

Endoscopic finding of a huge subepithelial lesion with central ulceration was noticed on fundus.

Fig. 5

Neoadjuvant therapy with imatinib for 4 months: there was no evidence of mass lesion in stomach on computed tomography.

References

1. Kang DY, Park CK, Choi JS, Jin SY, Kim HJ, Joo M, et al. Multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors: clinicopathologic and genetic analysis of 12 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007. 31:224–232.

2. DeMatteo RP, Lewis JJ, Leung D, Mudan SS, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Two hundred gastrointestinal stromal tumors: recurrence patterns and prognostic factors for survival. Ann Surg. 2000. 231:51–58.

3. Wu PC, Langerman A, Ryan CW, Hart J, Swiger S, Posner MC. Surgical treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the imatinib (STI-571) era. Surgery. 2003. 134:656–665.

4. Eisenberg BL, Smith KD. Adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy for primary GIST. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011. 67:Suppl 1. S3–S8.

5. Sym SJ, Ryu MH, Lee JL, Chang HM, Kim TW, Kim HC, et al. Surgical intervention following imatinib treatment in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). J Surg Oncol. 2008. 98:27–33.

6. Blay JY, Bonvalot S, Casali P, Choi H, Debiec-Richter M, Dei Tos AP, et al. Consensus meeting for the management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Report of the GIST Consensus Conference of 20-21 March 2004, under the auspices of ESMO. Ann Oncol. 2005. 16:566–578.

7. Kang YK, Kim KM, Sohn T, Choi D, Kang HJ, Ryu MH, et al. Clinical practice guideline for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumor in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2010. 25:1543–1552.

8. Eisenberg BL, Judson I. Surgery and imatinib in the management of GIST: emerging approaches to adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004. 11:465–475.

9. Blanke CD, Rankin C, Demetri GD, Ryan CW, von Mehren M, Benjamin RS, et al. Phase III randomized, intergroup trial assessing imatinib mesylate at two dose levels in patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing the kit receptor tyrosine kinase: S0033. J Clin Oncol. 2008. 26:626–632.

10. Andtbacka RH, Ng CS, Scaife CL, Cormier JN, Hunt KK, Pisters PW, et al. Surgical resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors after treatment with imatinib. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007. 14:14–24.

ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download