Abstract

Ospemifene—a third-generation selective estrogen receptor modulator approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2013—is an oral medication for the treatment of dyspareunia. In postmenopausal women with vulvovaginal atrophy, ospemifene significantly improves the structure and pH levels of the vagina, reducing dyspareunia. It is available as a 60-mg tablet; hence, women who may have had prior difficulty with vaginal administration or on-demand use of nonprescription lubricants and moisturizers would likely prefer this form of treatment. Preclinical studies demonstrated that ospemifene has an estrogen agonist action on the bone, reducing the cell proliferation of ductal carcinoma in an in situ model. Studies evaluating the safety of treatment for up to 52 weeks have shown that ospemifene is a safe medication with minimal impact on the endometrium. Further studies with larger number of subjects are necessary to better conclude its effects and long-term safety.

The decline in circulating estrogen during menopause results in structural changes, including thinning of the vaginal epithelium and atrophy of the vulva, vagina, and urinary tract.1 Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA)―calso known as atrophic vaginitis―is a common condition that affects up to 60% of postmenopausal women.23 It may present symptoms of vaginal dryness, burning, itching, irritation, and dyspareunia. These symptoms usually do not resolve naturally, or may even worsen, without effective treatments. In severe cases of VVA, patients may seek for surgical intervention.4

Although non-hormonal therapy, including over-the-counter lubricants and moisturizers, may help relieve symptoms of VVA, it does not treat the underlying condition.5 Black cohosh combined with St. John's wort was effective for eliminating symptom of hot flash, but did not show an estrogenic effect on VVA.67 Local estrogen therapy, such as estrogen creams, suppositories, and rings, are the treatment of choice for women with VVA who do not have any other postmenopausal symptoms. These may improve symptoms and restore vaginal anatomy.8 However, many women consider local agents inconvenient. Systemic hormone therapy has been used to treat menopausal symptoms and vaginal changes. The precipitous decline in the use of estrogen-based therapies in a 10-year period since the publication of results by The Women's Health Initiative trials has highlighted the need for a new, effective, non-hormonal (non-estrogen) treatment of VVA.

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) have estrogenic or anti-estrogenic effects depending on the tissues. While tamoxifen and toremifene are well-known agents for reducing the risk of breast cancer recurrence, they have been associated with an increased risk of endometrial cancer due to having estrogenic effects on the endometrium. Raloxifene was also initially developed to combat breast cancer, but it failed to prove superiority over tamoxifen in clinical trials. Data showing its positive effects on bone mineral density (BMD) led to the successful development of raloxifene to treat and prevent postmenopausal osteoporosis. Following the results from the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) trial, raloxifene was additionally approved in 2007 for the prevention of invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women at high risk. All of the above-mentioned agents―tamoxifen, toremifene, and raloxifene―have antiestrogenic effects on the vaginal tissue, making them poor alternatives for estrogen in the treatment of VVA.9

Ospemifene is the first non-hormonal SERM that has been approved for the treatment of dyspareunia associated with VVA. The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) included this agent in the treatment of moderate-to-severe dyspareunia associated with VVA.10 Consistent with other SERMs, such as tamoxifen, toremifene, and raloxifene, ospemifene possesses a distinctive mix of estrogenic and antiestrogenic tissue-specific effects. This review will summarize its mechanism of action and tissue-specific effects on the vagina, uterus, endometrium, breast, bone, and serum lipids.

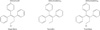

Ospemifene is a triphenylethylene, with a similar structure to tamoxifen and toremifene (Fig. 1). However, unlike the latter two agents, it does not contain an amino group. It has been speculated that the presence of the chlorine atom, in both toremifene and ospemifene, is responsible for the alterations in its interaction with DNA, preventing the formation of DNA adducts. For this, ospemifene may be considered somewhat safer than tamoxifen, regarding their carcinogenic potential. Each SERM has a unique tissue selectivity profile, and whether the compound acts as an estrogen receptor (ER) agonist or ER antagonist is thought to depend on (1) the specific conformational change of the receptor following its binding within the ligand-binding domain and (2) the cellular availability of coregulatory proteins. Ospemifene binds to both ERα and ERβ receptors, with a slightly greater affinity for ERα than ERβ (0.8% vs. 0.6%).11

Following oral administration, ospemifene reaches the peak median serum concentration in approximately 2 hours in fasting postmenopausal women. The bioavailability of ospemifene is increased two- to three-fold by food intake, hence it is recommended to be taken with food. Steady-state concentrations were observed after 7 days. Ospemifene is metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes in the liver, and it has a half-life of 26 hours.12 Approximately 75% and 7% of the dose was excreted in the feces and urine, respectively.13

The effect of ospemifene was compared with other SERMs in preclinical studies. When ospemifene was administered to ovariectomized rats, ospemifene induced a full agonist effect on the vaginal epithelium, while raloxifene induced only a minimal effect on the vagina.14 In a study by Kangas and Unkila15, ospemifene significantly increased the thickness of the vaginal epithelium and induced mucification and vacuolization in the vaginal epithelium. Unlike tamoxifen or raloxifene, ospemifene did not express liver toxicity in rats and mice.1116

The protective effect of ospemifene against breast cancer was demonstrated in preclinical studies. In an in situ mouse model, the cell proliferation was reduced significantly in ductal carcinoma when ospemifene was used.17 Ospemifene inhibits the appearance of dimethylbenzanthracene (DMBA)-induced mammary tumors and ER-dependent MCF-7 breast cancer cells, whereas no effect was found on ER-independent MDA-MB-231 cells.1819 The inhibitory effect was dose-dependent.11 When ospemifene was administered in three different doses (1 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg, and 50 mg/kg) to rats, the growth of tumors was 88%, 41%, and 21%, respectively, compared with 100% in the untreated group. The inhibitory effect was comparable with the effect of tamoxifen.19

The changes in the lipid profile was investigated in a pilot study in rhesus macaques using varying dose of ospemifene. An initial weekly oral dose of 35 mg/kg of ospemifene was administered for 3 weeks. Although there was a trend toward reduced total and low-density lipoproteins (LDL) cholesterol and increased triglycerides, the difference was statistically not significant. A different dose of 60 mg/day were administered for nine weeks, followed by 12 mg/day for 3 more weeks. Although the number of subjects were too small to make a statistical comparison, there was a trend towards lowering LDL and total cholesterol.20

The efficacy of ospemifene on postmenopausal women was supported by several large scale studies with a treatment period of 12 weeks and 52 weeks.1221222324 Among the approved SERMs, ospemifene is the only agent with a nearly full estrogen agonist effect on the vaginal epithelium, while having neutral- to slight-estrogenic effect in the endometrium. Therefore, ospemifene has been shown to be an effective treatment for VVA. More importantly, it has been shown to meet the requirements of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for primary efficacy in VVA. A meta-analysis of all published randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials reported that ospemifene significantly reduced parabasal cells by 37.5% and increased superficial cells by 9.2%. It also significantly reduced the vaginal pH level by 0.89 and major complaints of dyspareunia by a Likert scale of 0.37.25

In a phase III trial performed by McCall and DeGregorio26, 60 mg of ospemifene significantly reduced the symptoms of dyspareunia and vaginal dryness compared with the placebo. In another phase III trial, the proportion of parabasal/superficial cells and maturation index were significantly improved, and the vaginal pH level was significantly decreased.27 Recently, a combined analysis of two phase III trials2124 was published, and reported improvement in dyspareunia and vaginal dryness in three-quarters of women compared with 50% to 60% who received the placebo.28

Ospemifene has recently been approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to treat moderate-to-severe VVA in postmenopausal women who are not subject to local vaginal estrogen therapy.

Preclinical animal studies showed that ospemifene restored bone loss induced by ovariectomy. The effective dose for ospemifene to exhibit an estrogen agonist action on the bone in the two studies was 1 and 10 ng/kg, respectively.1129 In a phase II clinical study, ospemifene decreased bone resorption, as seen in significant dose-dependent decreases in N-terminal cross-linking telopeptide of type 1 collagen. Dose-dependent decreases in the markers of bone formation were also observed, as reflected in significant decreased levels of procollagen types 1C and 1N properties. Bone-specific alkaline phosphatase was also significantly reduced. These changes were similar to those seen in hormone-replacement treatments and with raloxifene. In a second double-blind phase II study, with parallel group randomization, ospemifene and raloxifene were found to produce similar changes in markers of bone resorption and bone formation. These preclinical and clinical studies have all shown that ospemifene has an estrogenic effect on the bone, confirming a comparable bone-restoring activity between ospemifene and raloxifene.

The extensive in vitro and in vivo animal models demonstrated that the cytotoxicity of ospemifene was markedly less than that of tamoxifen or raloxifene. From these studies, it was concluded that ospemifene acts as an estrogen antagonist in animal models of breast cancer. Moreover, ospemifene is only active when ERα is expressed, but not when only ERβ is present. In clinical trials with postmenopausal women, ospemifene had no adverse effects on the breast, and mammograms performed after 52 weeks of ospemifene were normal in all subjects of all groups. However, the Endocrine Society recommended against the use of ospemifene in their recent clinical practice guideline.30

No cases of endometrial carcinoma have been reported. In a phase II trial, endometrial cell proliferation was not observed, as evaluated by stable Ki-67 markers.31 According to 12-week phase II trials, the endometrial thickness, assessed by a transvaginal ultrasound, remained relatively unchanged.3132 In a phase III trial of postmenopausal women, with a treatment period of 12 weeks, taking either ospemifene―30 mg or 60 mg―or placebo, there was minimal change in the endometrial thickness, and their endometrial biopsy showed no cases of endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma.21 Extension studies demonstrated no significant endometrial changes associated with the use of ospemifene for at least up to 1 year of treatment.122224

The FDA concluded that ospemifene 60 mg per day was generally safe. However, the safety profile was based on a study with a treatment period of 52 weeks; as such, the safety of longer usage is uncertain. For this reason, they have added a black box warning concerning the possible increase in the risk of endometrial cancer related to the use of ospemifene. They also advised practitioners to use adequate diagnostic measures, such as endometrial sampling, to rule out malignancy in the event of undiagnosed persistent or recurrent abnormal genital bleeding. Ospemifene should be prescribed for the shortest duration consistent with treatment goals and risks for the individual woman.

In a phase II trial, three different daily doses of ospemifene (30 mg, 60 mg, and 90 mg) was administered. High-density lipoprotein (HDL) was significantly increased in the 90 mg/day group. Otherwise the result showed statistically nonsignificant decrease in total cholesterol and LDL, and a nonsignificant increase in HDL.33 In another phase II trial, three different daily doses of ospemifene (30 mg, 60 mg, and 90 mg) were compared with raloxifene. Only the 90-mg daily dose group showed comparable decrease in LDL. Total cholesterol was significantly lower in the raloxifene group. HDL remained unchanged in all groups, while a nonsignificant increase in triglyceride was found in the 90 mg/day group.32 A post-hoc analysis of 5 randomized, placebo-controlled trials has recently been published. A total of 2,166 postmenopausal women were included. Ospemifene administration resulted in significantly increased HDL in 3, 6, and 12 months, significantly reduced LDL at 3, 6, and 12 months, and significantly reduced total cholesterol at 6 months.34 These studies suggest that ospemifene does not have an adverse effect on lipid profiles.

Hot flashes were the most frequently reported side effects of ospemifene, with reported occurrence of 2% in the placebo group and 7.2% in the ospemifene group; however, it was not severe enough to lead to discontinuation.2125 The incidence rates of thromboembolic and hemorrhagic stroke were 0.72 and 1.45 per 1,000 women, respectively, in the ospemifene group and 1.04 and 0 per 1,000 women, respectively, in the placebo group. The incidence of deep vein thrombosis was 1.45 per 1,000 women in the ospemifene group and 1.04 per 1,000 women in the placebo group.35 Ospemifene is contraindicated in women with active arterial thromboembolic disease or a history of these conditions. If feasible, ospemifene should be discontinued for at least 4 to 6 weeks prior to surgery, and before any procedure with an increased risk of thromboembolism or during periods of prolonged immobilization.

Concomitant use of estrogens, as well as estrogen agonists/ antagonists, is prohibited. To date, in vivo experiments demonstrated that the metabolism of ospemifene was induced by rifampin and was inhibited by ketoconazole or fluconazole. Therefore, rifampin, ketoconazole and fluconazole should not be prescribed to women taking ospemifene.36 Coadministration of ospemifene with drugs that inhibit CYP450 3A4 (CYP3A4) and CYP450 2C9 (CYP2C9) may also increase the risk of adverse reactions.

Ospemifene is the first SERM approved to treat dyspareunia associated with VVA. Ospemifene has been shown to reverse the structural changes associated with VVA and relieve symptoms of dyspareunia. Ospemifene is generally safe, showing minimal impact on breast cancer or endometrial hyperplasia/carcinoma. Further studies are needed to evaluate its long-term efficacy and safety.

Notes

References

1. Calleja-Agius J, Brincat MP. Urogenital atrophy. Climacteric. 2009; 12:279–285.

2. Levine KB, Williams RE, Hartmann KE. Vulvovaginal atrophy is strongly associated with female sexual dysfunction among sexually active postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2008; 15:661–666.

3. Santoro N, Komi J. Prevalence and impact of vaginal symptoms among postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2009; 6:2133–2142.

4. Kim SH, Park ES, Kim TH. Rejuvenation using platelet-rich plasma and lipofilling for vaginal atrophy and lichen sclerosus. J Menopausal Med. 2017; 23:63–68.

5. Burich R, DeGregorio M. Current treatment options for vulvovaginal atrophy. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 6:141–151.

6. Park HM, Kang BM, Kim JG, Yoon BK, Lee BI, Cho SH, et al. The effect of black cohosh with St. John's wort (Feramin-Q(R)) on climacteric symptoms: multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 48:2403–2413.

7. Hong SN, Kim JH, Kim HY, Kim A. Effect of black cohosh on genital atrophy and its adverse effect in postmenopausal women. J Korean Soc Menopause. 2012; 18:106–112.

8. Kim M, Choi H. Changes in atrophic symptoms, the vaginal maturation index, and vaginal pH in postmenopausal women treated with vaginal estrogen tablets. J Korean Soc Menopause. 2010; 16:162–169.

9. Davies GC, Huster WJ, Lu Y, Plouffe L Jr, Lakshmanan M. Adverse events reported by postmenopausal women in controlled trials with raloxifene. Obstet Gynecol. 1999; 93:558–565.

10. Gennari L, Merlotti D, Valleggi F, Nuti R. Ospemifene use in postmenopausal women. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009; 18:839–849.

11. Qu Q, Zheng H, Dahllund J, Laine A, Cockcroft N, Peng Z, et al. Selective estrogenic effects of a novel triphenylethylene compound, FC1271a, on bone, cholesterol level, and reproductive tissues in intact and ovariectomized rats. Endocrinology. 2000; 141:809–820.

12. Goldstein SR, Bachmann GA, Koninckx PR, Lin VH, Portman DJ, Ylikorkala O. Ospemifene 12-month safety and efficacy in postmenopausal women with vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Climacteric. 2014; 17:173–182.

13. Koskimies P, Turunen J, Lammintausta R, Scheinin M. Single-dose and steady-state pharmacokinetics of ospemifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, in postmenopausal women. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013; 51:861–867.

14. Unkila M, Kari S, Yatkin E, Lammintausta R. Vaginal effects of ospemifene in the ovariectomized rat preclinical model of menopause. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2013; 138:107–115.

15. Kangas L, Unkila M. Tissue selectivity of ospemifene: pharmacologic profile and clinical implications. Steroids. 2013; 78:1273–1280.

16. Hellmann-Blumberg U, Taras TL, Wurz GT, DeGregorio MW. Genotoxic effects of the novel mixed antiestrogen FC-1271a in comparison to tamoxifen and toremifene. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000; 60:63–70.

17. Burich RA, Mehta NR, Wurz GT, McCall JL, Greenberg BE, Bell KE, et al. Ospemifene and 4-hydroxyospemifene effectively prevent and treat breast cancer in the MTag.Tg transgenic mouse model. Menopause. 2012; 19:96–103.

18. Taras TL, Wurz GT, DeGregorio MW. In vitro and in vivo biologic effects of Ospemifene (FC-1271a) in breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2001; 77:271–279.

19. Wurz GT, Read KC, Marchisano-Karpman C, Gregg JP, Beckett LA, Yu Q, et al. Ospemifene inhibits the growth of dimethylbenzanthracene-induced mammary tumors in Sencar mice. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005; 97:230–240.

20. Wurz GT, Hellmann-Blumberg U, DeGregorio MW. Pharmacologic effects of ospemifene in rhesus macaques: a pilot study. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008; 102:552–558.

21. Bachmann GA, Komi JO. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Menopause. 2010; 17:480–486.

22. Simon JA, Lin VH, Radovich C, Bachmann GA. One-year long-term safety extension study of ospemifene for the treatment of vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women with a uterus. Menopause. 2013; 20:418–427.

23. Simon J, Portman D, Mabey RG Jr. Long-term safety of ospemifene (52-week extension) in the treatment of vulvar and vaginal atrophy in hysterectomized postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2014; 77:274–281.

24. Portman DJ, Bachmann GA, Simon JA. Ospemifene, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator for treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2013; 20:623–630.

25. Cui Y, Zong H, Yan H, Li N, Zhang Y. The efficacy and safety of ospemifene in treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2014; 11:487–497.

26. McCall JL, DeGregorio MW. Pharmacologic evaluation of ospemifene. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2010; 6:773–779.

27. Portman D, Palacios S, Nappi RE, Mueck AO. Ospemifene, a non-oestrogen selective oestrogen receptor modulator for the treatment of vaginal dryness associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Maturitas. 2014; 78:91–98.

28. Nappi RE, Panay N, Bruyniks N, Castelo-Branco C, De Villiers TJ, Simon JA. The clinical relevance of the effect of ospemifene on symptoms of vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Climacteric. 2015; 18:233–240.

29. Qu Q, Härkönen PL, Väänänen HK. Comparative effects of estrogen and antiestrogens on differentiation of osteoblasts in mouse bone marrow culture. J Cell Biochem. 1999; 73:500–507.

30. Stuenkel CA, Davis SR, Gompel A, Lumsden MA, Murad MH, Pinkerton JV, et al. Treatment of symptoms of the menopause: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015; 100:3975–4011.

31. Rutanen EM, Heikkinen J, Halonen K, Komi J, Lammintausta R, Ylikorkala O. Effects of ospemifene, a novel SERM, on hormones, genital tract, climacteric symptoms, and quality of life in postmenopausal women: a double-blind, randomized trial. Menopause. 2003; 10:433–439.

32. Komi J, Lankinen KS, Härkönen P, DeGregorio MW, Voipio S, Kivinen S, et al. Effects of ospemifene and raloxifene on hormonal status, lipids, genital tract, and tolerability in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2005; 12:202–209.

33. Ylikorkala O, Cacciatore B, Halonen K, Lassila R, Lammintausta R, Rutanen EM, et al. Effects of ospemifene, a novel SERM, on vascular markers and function in healthy, postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2003; 10:440–447.

34. Archer DF, Altomare C, Jiang W, Cort S. Ospemifene's effects on lipids and coagulation factors: a post hoc analysis of phase 2 and 3 clinical trial data. Menopause. 2017; DOI: 10.1097/gme.0000000000000900.

35. Shionogi Inc. Osphena®: prescribing package insert. Florham Park, NJ: Shionogi Inc;2015.

36. Lehtinen T, Tolonen A, Turpeinen M, Uusitalo J, Vuorinen J, Lammintausta R, et al. Effects of cytochrome P450 inhibitors and inducers on the metabolism and pharmacokinetics of ospemifene. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2013; 34:387–395.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download