Abstract

Methods

This study is a secondary analysis of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Fifty-four out of 60 patients were able to successfully complete the original study. Seven out of 54 patients were excluded because they were not overweight and obese. Thus, 47 women were included in this secondary analysis. Of these 47 women, 22 were in the fennel group and 25 were in placebo group. Body weight, body mass index (BMI) as well as fat distribution was measured at the baseline and after a three-month follow-up.

It has been shown that estrogen deficiency induced by menopause causes a number of changes in body composition, including reduced lean mass and increased body weight or abdominal fat.1 The central distribution of body fat is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease.2 Use of hormone therapy (HT) in menopausal women prevents the central distribution of body fat and loss of lean mass.34 However, postmenopausal women undergoing hormone replacement therapy (HRT) tend to abandon due to HRT-related side effects, such as breast swelling/tenderness, spotting, bloating and bleeding.5 As such, a large number of postmenopausal women have a preference for compounds with non-hormonal materials such as phytoestrogens, which offer a safer option. Fennel is regarded as phytoestrogen-a type of herb belonging to the apiaceae family which is assumed to be an ancient medicinal plant and has been used in Iranian traditional medicine for ages. It has known antioxidant, cytotoxic, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial estrogenic, hypotensive and antithrombotic features.6 One animal study on the effect of fennel on body weight, feed intake food efficiency rate and serum leptin found that it could reduce the rate of food efficiency in rats.7 One human study in South Korea demonstrated its remarkable effect in controlling appetite in overweight women.8 However, there is a paucity of studies assessing the effect of fennel on body composition among postmenopausal women. The goal of this secondary analysis is to assess the effect of fennel on body composition in post-menopausal women.

A secondary analysis was conducted on data derived from a randomized controlled trial that was intended to assess the effect of fennel on lipid profile and bone density in Iranian postmenopausal women. The ordinal protocol was approved by Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Science (No. 930804). Fifty-four out of 60 patients were able to successfully complete the original study. Seven out of 54 patients were excluded because they were not overweight and obese. Thus, 47 women were included in this secondary analysis. Of these 47 women, 22 were in the fennel group and 25 were in placebo group. Body weight, body mass index (BMI) as well as fat distribution was measured at the baseline and after a three-month follow-up.

Inclusion criteria were: healthy postmenopausal women (no vaginal bleeding for 1 year) aged above 40 years who had a normal mammogram over the last year. The exclusion criteria included using any fluoride or bisphosphonates, current (or over the past 6 months) use of estrogen or calcitonin, endometrial thickness >5 mm, regular ingestion of phytoestrogen or soy-based products, regular physical exercise and allergy to fennel.

All participants signed informed consent forms regarding the voluntary basis of their participation in the study and that they could abandon the trial at any time. To ensure allocation concealment, researchers printed random numbers on non-transparent sealed envelopes. The envelopes contained soft capsule for 30 days. All subjects were requested to take soft capsules three times a day. The soft 100-mg fennel capsules were standardized to 71 to 90 mg anethole. Placebo group received capsules with identical shape and size. Both fennel and placebo were filled with sunflower oil (mineral oil). The sequence and concealment of allocation was carried out by a research assistant, who was not directly involved in the study. The degree of compliance was evaluated in terms of the number of capsules given back by the patients at the end of trial.

Following the overnight fasting, the waist circumference of participants was measured using a soft measuring tape, which was placed directly on the narrowest point between iliac crest and lower rib margin. Also, the hip circumference was measured at the widest area over the great trochanters and the waist-hips circumference ratio was calculated. The weight and height were measured by one of the researchers. Subjects were barefooted and had light indoor clothing on during bodyweight measurements (it weighed about 100 g). The BMI was also computed by dividing weight (kg) by height (m2).

Data were checked for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality. The paired t-test was used to determine the difference before and after treatment. The student t-test (between groups), was utilized to compare the two treatment groups. Statistical tests were two-sided, and a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Covariance analysis was performed to compare the effect of intervention on post treatment scores after controlling BMI difference at the baseline. Since this was a secondary analysis, the sample size was not determined, but post-hoc calculation of statistical power was conducted by PASS/NCSS software (NCSS, Kaysville, UT, USA) to assess the power of findings.

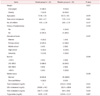

The mean age of menopausal women was 57.36 years in fennel group and 56.72 in the placebo group. The mean length of menopause was 8.61 years in the fennel group and 7.39 years in the placebo group. Women in the experimental and control groups had 4.55 and 3.86 children. Moreover, the mean BMI in the fennel and placebo groups was 29.50 ± 2.98 and 32.04 ± 4.1 respectively. The two groups were identical in variables such as age, length of menopause, history of hysterectomy; number of children, body weight, level of educational, marital status income level and lipid profile at the baseline except for BMI, as show in Table 1 and 2.

Of 60 patients, 5 in the fennel group and 1 in the placebo group abandoned the trial. The former group complained of allergic rash (n = 1), weight gain (n = 1), hypertension (n = 1) and vaginal bleeding (n = 2). One patient in the placebo group complained of stomachache. However, none of these (vaginal bleeding) was related to malignancy or endometrial proliferation. Also, 7 patients were excluded because they did not meet the obesity criteria. Comparison of fennel and placebo groups did not show any significant change in body weight, BMI, waist and hip circumferences and fat distribution, as shown in Table 2. Also, the results of paired t-test did not reveal any variation in these parameters in both groups before and after the 12-week trial. In both groups, high compliance was observed.

At the baseline, BMI was assessed either as a continuous or categorized variable. There was a significant different between the two groups in this regard, with subjects in the placebo group having more BMI. As such, we used covariance analysis, with the results indicating that if BMI difference was controlled at the baseline, the effect of intervention would not be statistically significant (P = 0.356) (data were not showed).

As far as we know, this is the first study to assess the effects of fennel on body composition in post-menopausal women with excess weight. According to the results of this study, fennel did not have any significant effect on body weight, BMI, waist and hip circumferences and waist-hip ratio (WHR) over a three-month period. All variables except for BMI were identical in both groups. However, the researcher was blind to BMI findings at the baseline. The fact that fennel did not have any positive effect on body composition rejects our hypothesis, which was based on the study of Bae et al..8 The results of two studies by Bae et al.8 showed that taking fennel as tea (containing 2 g of dried tea) or as aromatherapy (2-4 drops of fennel oil on dried cotton)9 could suppress appetite in overweight women.

This effect was attributed to the content of trans-anethole, which acted on amphetamine and helped appetite control.8 The results of this study are consistent with recent data derived from animal models according to which inhalation of essential oils has no effect on decreasing body weight in rats.7 Similarly, our findings did not show any significant increase in body weight of subjects. One possible justification for the results reported by Bae et al.8 and the present study is that fennel may suppress appetite, but it also slightly increases in body weight and fat distribution. Further studies are required to examine the effect of fennel on both appetite and body composition. Our review of literature showed the paucity of human studies about the effects of fennel on body composition. However, considering that phytoestrogenes are an active biological compound in fennel, we incorporated studies that assessed phytoestrogen effects such as flaxseed and soy on body composition.1011121314 Five out of 10 studies reviewed in the meta-analysis of Zhang et al.15 suggested that soy intake led to an increase in body weight, though this reduction was not statistically significant. In another study by Machado et al.16 75 overweight adolescents were randomly assigned to three groups of brown flaxseed (28 g/day), golden flaxseed (28 g/day), and control group. The results showed a body weight increased from 59.28 to 61.25 (P < 0.001) in the brown flaxseed group and from 63.84 to 64.88 (P = 0.010) in the golden flaxseed, though it remained unchanged in the control group.16 These findings are consisted with our study, according to which phytoestrogens may lead to a slight increase in body weight. Part of discrepancy between our findings and those reported in other studies may be due to different ingredients of pill (tablet) and teas. Another reason could be that fennel might have varying effects on menopausal compared to others age group. One limitation of this study was its failure to control lifestyle habits like physical activity and diet. However, subjects were asked not to change their usual diet and physical activity over a three-month period. Moreover, although previous study showed that fennel might suppress appetite, we only assessed the effect of fennel on body composition. Further research studies should address the change of diet pattern during the treatment. The results of a post-study power analysis indicated that the current sample size had only 22% and 15% power in identifying the difference between placebo and fennel groups in terms of body weight and fat distribution.

References

1. Liu ZM, Ho SC, Chen YM, Woo J. A six-month randomized controlled trial of whole soy and isoflavones daidzein on body composition in equol-producing postmenopausal women with prehypertension. J Obes. 2013; 2013:359763.

2. Misso ML, Jang C, Adams J, Tran J, Murata Y, Bell R, et al. Differential expression of factors involved in fat metabolism with age and the menopause transition. Maturitas. 2005; 51:299–306.

3. Haarbo J, Marslew U, Gotfredsen A, Christiansen C. Post-menopausal hormone replacement therapy prevents central distribution of body fat after menopause. Metabolism. 1991; 40:1323–1326.

4. Sørensen MB, Rosenfalck AM, Højgaard L, Ottesen B. Obesity and sarcopenia after menopause are reversed by sex hormone replacement therapy. Obes Res. 2001; 9:622–626.

5. Björn I, Bäcksröm T. Drug related negative side-effects is a common reason for poor compliance in hormone replacement therapy. Maturitas. 1999; 32:77–86.

6. Rahimi R, Ardekani MR. Medicinal properties of Foeniculum vulgare Mill. In traditional Iranian medicine and modern phytotherapy. Chin J Integr Med. 2013; 19:73–79.

7. Hur MH, Kim C, Kim CH, Ahn HC, Ahn HY. The effects of inhalation of essential oils on the body weight, food efficiency rate and serum leptin of growing SD rats. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2006; 36:236–243.

8. Bae J, Kim J, Choue R, Lim H. Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) and Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) tea drinking suppresses subjective short-term appetite in overweight women. Clin Nutr Res. 2015; 4:168–174.

9. Kim SJ, Kim KS, Shin SU, Choi YM, Kang BG, Yoon YS, et al. A clinical study of decrease appetite effects by aromatherapy using foeniculum vulgare mill (fennel) to female obese patients. J Korean Orient Assoc Stud Obes. 2005; 5:9–20.

10. Puska P, Korpelainen V, Høie LH, Skovlund E, Smerud KT. Isolated soya protein with standardised levels of isoflavones, cotyledon soya fibres and soya phospholipids improves plasma lipids in hypercholesterolaemia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of a yoghurt formulation. Br J Nutr. 2004; 91:393–401.

11. Arjmandi BH, Lucas EA, Khalil DA, Devareddy L, Smith BJ, McDonald J, et al. One year soy protein supplementation has positive effects on bone formation markers but not bone density in postmenopausal women. Nutr J. 2005; 4:8.

12. Sites CK, Cooper BC, Toth MJ, Gastaldelli A, Arabshahi A, Barnes S. Effect of a daily supplement of soy protein on body composition and insulin secretion in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2007; 88:1609–1617.

13. Garrido A, De la, Hirsch S, Valladares L. Soy isoflavones affect platelet thromboxane A2 receptor density but not plasma lipids in menopausal women. Maturitas. 2006; 54:270–276.

14. Weickert MO, Reimann M, Otto B, Hall WL, Vafeiadou K, Hallund J, et al. Soy isoflavones increase preprandial peptide YY (PYY), but have no effect on ghrelin and body weight in healthy postmenopausal women. J Negat Results Biomed. 2006; 5:11.

15. Zhang YB, Chen WH, Guo JJ, Fu ZH, Yi C, Zhang M, et al. Soy isoflavone supplementation could reduce body weight and improve glucose metabolism in non-Asian postmenopausal women-a meta-analysis. Nutrition. 2013; 29:8–14.

16. Machado AM, de Paula H, Cardoso LD, Costa NM. Effects of brown and golden flaxseed on the lipid profile, glycemia, inflammatory biomarkers, blood pressure and body composition in overweight adolescents. Nutrition. 2015; 31:90–96.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download