Abstract

The term collision tumor refers to the coexistence of two adjacent but histological distinct tumors with no histological admixture at the interface. Collision tumors involving ovaries are extremely rare. A collision tumor composed of a dermoid cyst and fibrothecoma is extremely rare in menopausal women. The mechanism of the development of collision tumor is uncertain. During clinical evaluation, differentiation of characters of these ovarian tumors is important to decide appropriate treatment strategies and for good prognosis. We report an unusual clinical manifestation of the torsion of a dermoid cyst and fibrothecoma in the right ovary with postmenopausal bleeding.

Dermoid cysts are the most frequently occurring tumors among ovarian germ cell tumors, accounting for more than 20% of all ovarian neoplasms.1 They present most commonly in women younger than 20 years of age, but sometimes occur in menopausal women at a rate of about 10% to 20%. Fibrothecomas are ovarian tumors of gonadal stromal origin, mesenchymal cell tumors composed of theca-like elements and fibrous tissue, and account for about 0.4% to 8% of all ovarian tumors.2 A collision tumor is defined as a tumor in which the different neoplastic components remain histologically distinct and are separated from each other by narrow stroma or their respective basal lamina. We report the case of a 77 year old woman who presented with postmenopausal bleeding (PNB) due to the torsion of a collision tumor comprising a dermoid cyst and fibrothecoma.

A 77-year-old postmenopausal woman presented with vaginal bleeding with a week-long history and a large pelvic mass associated with lower abdominal discomfort for 3 months. The patient complained of pain, but had no fever, chills and significant gastrointestinal symptoms. She had gone through menopause at the age of 52 and was not taking any hormone replacement.

She had no significant past medical history, familial history or operation history. On pelvic examination, a relatively hard, movable, non-tender mass as large as a double man's fist was palpated on the right lower abdomen. The vagina, cervix and uterus were normal. There was no guarding or rebound tenderness.

The hemogram revealed anemia with a hemoglobin level of 9.8 g/dL and a hematocrit of 29.8%. Biochemical investigations, tumor markers and hormonal values were within normal limits. The Pap test was normal although she had never gotten it done before.

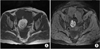

Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a 12 × 12 × 11.5 cm sized, well-marginated, bilobulated cystic mass with some solid areas in the right pelvic cavity. With enhancement setting, the mass exhibited relatively high enhancement and heterogenicity (Fig. 1). There was no other abnormal finding on images and no pelvic lymph node enlargement was observed.

Endometrial aspiration was done, confirming historically normal proliferative endometrium.

Under general anesthesia, surgical exploration was performed with a suspicion of ovarian tumor.

The uterus and left adnexa appeared normal, and a large right ovarian tumor of approximately 12 cm diameter was rotated counterclockwise with a 720 degree arc. No enlargement of lymph nodes around the mass was found. Right salpingo-oophorectomy was performed for frozen biopsy. After confirming the frozen pathologic results as fibrothecoma and benign dermoid cyst, total hysterectomy and left salpingo-oophorectomy were performed. Permanent pathological examination demonstrated a collision tumor composed of fibrothecoma and benign dermoid cyst. Macroscopically, the resected tumors in both cases showed a unilocular cystic tumor adjacent to a solid tumor. Microscopically, the cystic tumors were composed of cutaneous tissues and the solid tumors consisted of spindle cells with lipid-rich cytoplasm, arranged in interlacing bundles. The cystic tumor and the solid tumor were completely separate and no transitional features were recognized histologically (Fig. 2). The postoperative course was uneventful.

She recovered well and was discharged on postoperative day 9.

Dermoid cyst is the most frequently occurring ovarian germ cell tumor, accounting for 20% of all ovarian tumors, usually in patients of child bearing age. Unlike all other germ cell tumors, the incidence is variable from infancy to old age. It may have complications such as rupture, torsion, infection and malignant changes. Malignant changes in benign dermoid cysts have been recorded as occurring in 1.0% to 1.8% of cases, usually in patients older than 40 years of age or menopausal women.

Fibrothecomas are ovarian tumors of gonadal stromal origin, composed of theca-like elements and fibrous tissue. These tumors are usually benign and occur most frequently in menopausal women. Clinically, most patients present amenorrhea, irregular menstruation or atypical postmenopausal vaginal bleeding.

A collision tumor represents the coexistence of two adjacent but histologically different neoplasms occurring in the same organ with completely different basal layers or stroma. Collision tumors occur in various organs such as the esophagus, stomach and thyroid, but they are extremely rare in the ovaries. The most common histologic combination of collision tumors of the ovary consists of teratoma and mucinous tumors.3

During clinical evaluation, differentiation of the characters of these ovarian tumors is important for appropriate treatment strategies and prognosis. Ultrasound is the most common tool used to evaluate ovarian masses, but it is impossible to determine the exact size and direction if the mass is huge. It is also impossible to determine whether other complicated masses are present or not. Computed tomography and MRI are more useful diagnostic tools for huge ovarian masses. In this case, the mass was very large and was located just beneath the skin so the MRI was helpful.

PMB is vaginal bleeding that occurs at least 12 months after your periods have stopped. PMB is a common problem representing 5% of all gynecology outpatient attendances.4 The most common causes of bleeding after menopause include thinning of the reproductive tract tissues and hormone therapy.5 In some cases, bleeding can signal cancer of the uterine lining or cervical cancer. Other possible causes include fibroids, small growths in the uterus or cervix, known as polyps, and ovarian cancer, especially estrogen-secreting ovarian tumors. Although most women with PMB will not have significant pathology, the priority is to exclude malignancy.6

Torsions of ovary, tube, paratubal cysts or adnexa are not common, but they are major causes of acute abdominal pain, local infarction of abdominal organs, and sometimes gynecologic emergencies, accounting for approximately 2.7% of all gynecologic emergencies.

Torsion may occur with no specific cause, but there are risk factors like bowel movement, bladder changes, and changes in uterine size during pregnancy, intra-abdominal pressure during vomiting, coughing or abdominal trauma.7 The incidence of ovarian torsion is about 1.5 times more frequent on the right side than on the left because of the narrow space on the left side due to the sigmoid colon as well as the increased bowel movement of the terminal ileum and cecum on the right side. The most common symptom of ovarian torsion is acute lower abdominal pain. The pain is usually aggravated during elevation, exercise and coitus. It is accompanied by nausea, vomiting and anxiety due to a sensitized autonomic nervous system. The most important sign in physical examination is a palpable intrapelvic mass. If it is complicated with infarction, fever and leukocytosis may present. The period of symptoms can be variable from a few hours to a few months, but sometimes, there may be no symptoms at all. The diagnosis of ovarian torsion is nonspecific, and it is suspected on the basis of peritoneal signs, sonographic findings such as cystic, mixed pelvic mass and fluid collection in the Douglas pouch. Recent studies have reported that color Doppler flow can be used as a diagnostic tool by proofing ovarian arterial and venous flow, but partial torsion of the ovary cannot be observed by color Doppler due to the dual blood supply of the ovary.8

Menopausal women with acute abdominal pain and a palpable mass in the adnexa usually have the probability of an ovarian tumor with a chance of torsion. However, it is not easy to diagnose before surgical treatment due to nonspecific symptoms, clinical and physical findings and radiographic findings. It is difficult to differentially diagnose from other emergent conditions. The treatment of ovarian tumor in menopausal women is generally total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. With the suspicion of malignancy, an appropriate staging operation is needed. Here we present a successfully treated case of a 77 year old woman with collision tumor composed of dermoid cyst and fibrothecoma in the right ovary with a review of literature.

This study shows that the hormonal changes caused by sex cord stromal tumor can cause postmenopausal uterine bleeding and can have significant influence on collision tumors involving dermoid cysts and fibrothecoma. The torsion of this kind of unique combination of tumors has never been reported, thus this study has its remarkability.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) T1-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) image shows a multiloculated cystic mass with heterogenous low signal intensity in the right pelvic cavity. (B) T2-weighted MR image shows heterogenous high signal intensity of the mass.

Fig. 2

Microscopic features of collision tumor. (A) Microscopic features of solid component of ovarian fibrothecoma composed of fascicles of spindle cells with centrally placed nuclei and a moderate amount of pale cytoplasm without atypia or myxoid change (H & E, original magnification ×100). (B) Microscopic features of cystic component of ovarian mature cystic teratoma composed of skin adnexa and cystic cavity lined by squamous epithelium (H & E, original magnification ×100).

References

1. Pepe F, Panella M, Pepe G, et al. Dermoid cysts of the ovary. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1986; 7:186–191.

2. Costa MJ, Morris R, DeRose PB, et al. Histologic and immunohistochemical evidence for considering ovarian myxoma as a variant of the thecoma-fibroma group of ovarian stromal tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1993; 117:802–808.

3. Kim SH, Kim YJ, Park BK, et al. Collision tumors of the ovary associated with teratoma: clues to the correct preoperative diagnosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999; 23:929–933.

4. Lee SH, Kim TH, Lee HH, et al. The clinical manifestation of the gynecologic emergency in postmenopausal women. J Korean Soc Menopause. 2012; 18:119–123.

5. Choi H, Kang BM, Kim JG, et al. Endometrial safety and vaginal bleeding patterns of an oral continuous combined regimens of estradiol and drospirenone for postmenopausal women: A multicenter, double blind, randomized, placebo controlled study. J Korean Soc Menopause. 2006; 12:127–133.

6. Park J, Kim TH, Lee HH, et al. Endosalpingiosis in postmenopausal elderly women. J Menopausal Med. 2014; 20:32–34.

7. Lee CH, Raman S, Sivanesaratnam V. Torsion of ovarian tumors: a clinicopathological study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1989; 28:21–25.

8. Lee EJ, Kwon HC, Joo HJ, et al. Diagnosis of ovarian torsion with color Doppler sonography: depiction of twisted vascular pedicle. J Ultrasound Med. 1998; 17:83–89.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download