Abstract

Background

This study characterized clonal IG heavy V-D-J (IGH) gene rearrangements in South Indian patients with precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (precursor B-ALL) and identified age-related predominance in VDJ rearrangements.

Methods

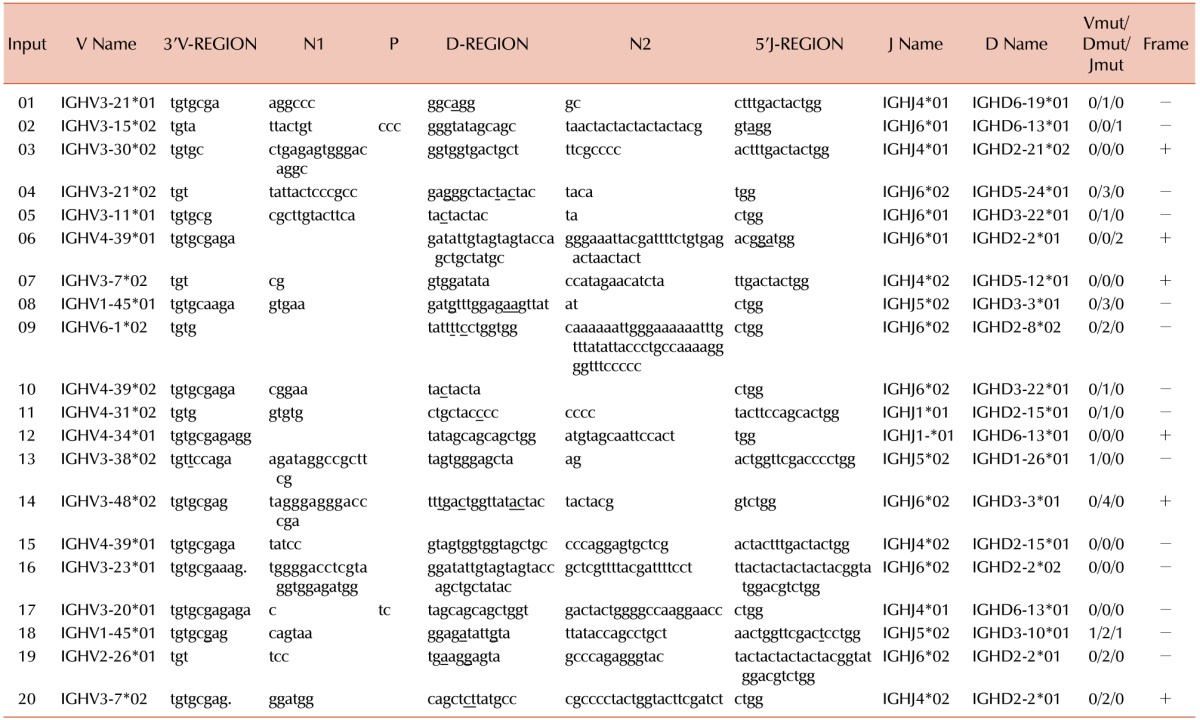

IGH rearrangements were studied in 50 precursor B-ALL cases (common ALL=37, pre-B ALL=10, pro-B ALL=3) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) heteroduplex analysis. Twenty randomly selected clonal IGH rearrangement sequences were analyzed using the IMGT/V-QUEST tool.

Results

Clonal IGH rearrangements were detected in 41 (82%) precursor B-ALL cases. Among the IGHV1-IGHV7 subgroups, IGHV3 was used in 25 (50%) cases. Among the IGHD1-IGHD7 genes, IGHD2 and IGHD3 were used in 8 (40%) and 5 (25%) clones, respectively. Among the IGHJ1-IGHJ6 genes, IGHJ6 and IGHJ4 were used in 9 (45%) and 6 (30%) clones, respectively. In 6 out of 20 (30%) IGH rearranged sequences, CDR3 was in frame whereas 14 (70%) had rearranged sequences and CDR3 was out of frame. A somatic mutation in Vmut/Dmut/Jmut was detected in 14 of 20 IGH sequences. On average, Vmut/Dmut/Jmut were detected in 0.1 nt, 1.1 nt, and 0.2 nt, respectively.

Conclusion

The IGHV3 gene was frequently used whereas lower frequencies of IGHV5 and IGHV6 and a higher frequency of IGHV4 were detected in children compared with young adults. The IGHD2 and IGHD3 genes were over-represented, and the IGHJ6 gene was predominantly used in precursor-B-ALL. However, the IGH gene rearrangements in precursor-B-ALL did not show any significant age-associated genotype pattern attributed to our population.

During early B cell differentiation, the rearrangement of immunoglobulin (IG) genes occurs by combining the germline variable (V), diversity (D), and joining (J) genes [1]. Precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (precursor B-ALL) results from a transformed hematopoietic cell with complete or partial VDJ recombination within the immunoglobulin heavy (IGH) chain gene [2].

By combinatorial diversity, each lymphocyte thereby acquires a specific V-(D)-J rearrangement that codes for the variable domain of IG chains. The IGH locus contains 27 IGHD genes, 6 IGHJ genes, and 38-46 functional IGHV genes [3]. The 3′ end of the IGHV region, both ends of the IGHD region, and the 5′ end of the IGHJ region are trimmed by an exonuclease during the rearrangement, and nucleotides are added randomly by the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) at the D-J and V-D-J junctions, forming the N-diversity regions before ligation [1]. The V-D-J junction codes for third complementarity-determining region (CDR3), which is the most diverse region of the V domain [4]. The junction includes the CDR3 with its two anchors, 104 (2nd-CYS) and 118 (J-PHE/J-TRP of the J region) [56].

In B-lineage cells, rearrangement of one D gene and one JH gene are followed by the addition of one of the numerous VH genes to the fused D-JH segments. If successful, the resulting VH-DH-JH rearrangement is transcribed into RNA that is spliced to the constant region RNA (Cµ) before translation into an Ig heavy (µ) chain in the pre-B cell. If the initial rearrangement produces a sequence that cannot be translated (nonproductive or abortive rearrangement), then rearrangement of the IGH locus proceeds on the other allele [7].

This study aimed to characterize the clonal IGH gene rearrangements and usage of the IGHV, IGHD, and IGHJ genes in south Indian patients with precursor B-ALL. We also tested whether there was any age-related predominance in VDJ rearrangements in precursor B-ALL, as was previously seen in T-cell receptor gamma (TCRG) and TCR delta (TCRD) gene rearrangements [8]. This is the first study to investigate the IGH rearranged sequences in precursor B-ALL.

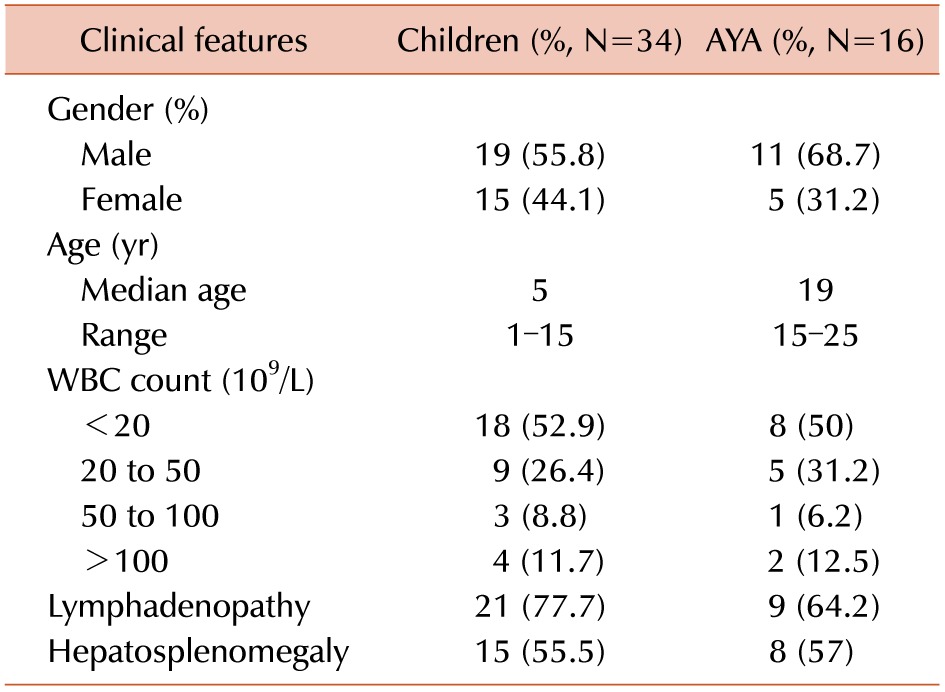

Bone marrow (BM) and peripheral blood (PB) samples were obtained from 50 precursor B-ALL (37 common ALL, 10 Pre-B ALL and 3 Pro-B ALL) patients prior to starting treatment. The patients were diagnosed with ALL based on standard FAB classification and immunophenotyping at Department of Hematology and Immunology, Cancer Institute (WIA), Chennai. Among these patients, 34 were children and 16 were adolescents and young adults (Table 1). All the pediatric and young adult patients received the MCP 841 protocol with informed consent [9].

Two milliliters of BM and 10 mL of PB were collected from the patients prior to starting the treatment. Mononuclear cells (MNCs) from BM and PB were separated by the Ficoll Hypaque (density: 1.077 g/mL, Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) density gradient method. Cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and were stored at −70℃ until use.

The frozen MNCs were thawed at room temperature, and DNA was isolated using a QIAamp kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer's instructions and the quality was checked by amplifying the ABL1 housekeeping gene.

For the identification of IGH rearrangements, PCR reactions were set up for each sample. A 50 µL PCR reaction containing 10X PCR buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 250 µM dNTPs (AB gene, Epsom, UK), 1.5 U of Hotstart Taq Polymerase (AB gene), 15 pmol each of a forward FR1VH (IGHV1/IGHV7, IGHV2, IGHV3, IGHV4, IGHV5, IGHV6) and reverse primer (IGHJ), and 200 ng of genomic DNA. PCR reactions were performed using a Geneamp 9700 thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA). The PCR conditions included preactivation of the enzyme for 10 min at 94℃ followed by 35 cycles at 92℃ for 60 sec, 60℃ for 1 min 15 sec and 72℃ for 2 min and a final extension of 10 min at 72℃. The amplified products were visualized by electrophoresing on a 3% agarose gel. The sequences of PCR primers were described previously by Szczepański et al. [10].

The clonal gene rearrangements in malignant leukemic cells were distinguished from polyclonal normal cells using heteroduplex analysis. For the analysis, 12 µL of the amplified PCR product was denatured at 94℃ for 5 min to obtain single-stranded PCR products. This was followed by cooling on ice for 60 min to induce the renaturation of the products. The samples were then loaded on a 6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel with 0.5X Tris-borate buffer and run at 45 V overnight. A clonal rearrangement was identified by the presence of a discrete band in the gel [11].

The homoduplex PCR product was excised from the gel and ethanol-precipitated as described. Three microliters of the eluted DNA was re-amplified with the same set of primers used for the PCR reaction. Two microliters of the re-amplified PCR product was sequenced in both the forward and reverse directions. For sequencing, the Big Dye Terminator Cycle sequencing Ready Reaction kit v3.0 (Applied Biosystems) was used and the reaction products were analyzed in ABI 310 Genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

The sequences obtained were analyzed using IMGT/V-QUEST from IMGT, the international ImmunoGeneTics information system (http://www.imgt.org) [6]. IMGT/V-QUEST was used to compare the sequences with its reference directory that contains the human germline IGHV, IGHD, and IGHJ genes, allowing the identification of genes involved in the V-D-J rearrangements and analysis of the somatic hypermutations. The analysis of the junctions was performed by IMGT/Junction analysis, which is integrated in IMGT/V-QUEST [12].

The clinical features of the patients are presented in Table 1. The clinical features of the children and young adult patients were similar, and there were no significant differences between the two groups. The frequency of IGH gene rearrangements is illustrated in Fig. 1.

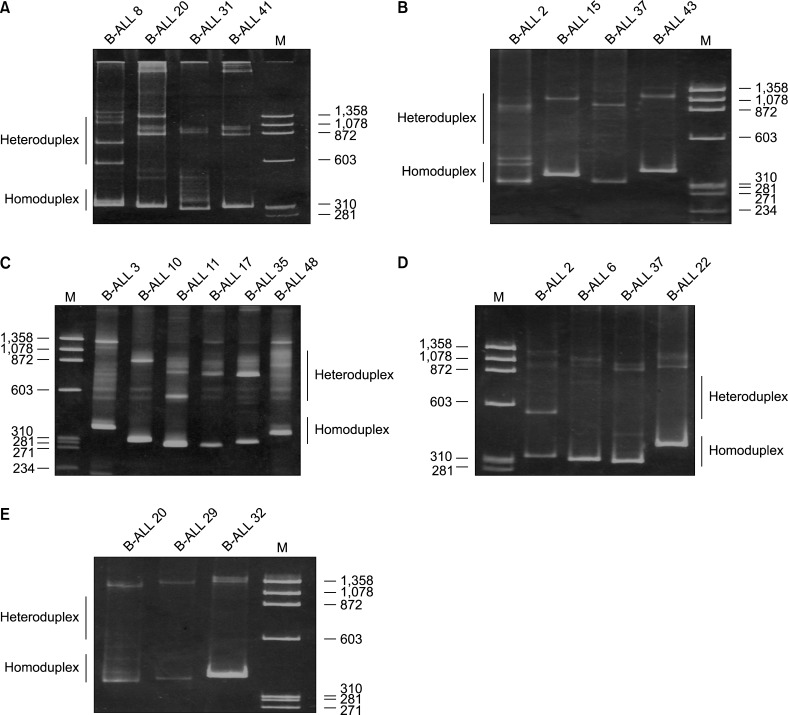

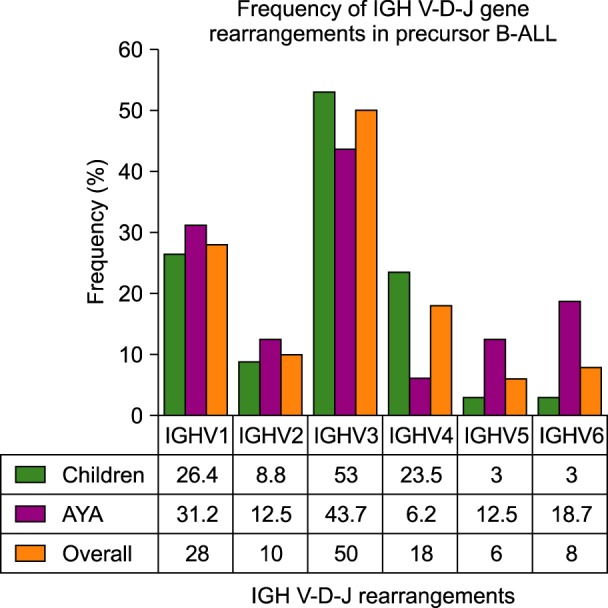

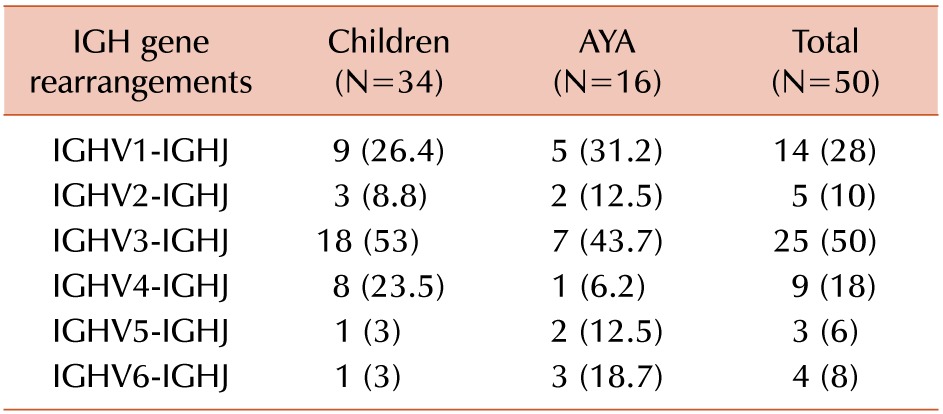

One or more clonal IGH gene rearrangement were detected in 41 of 50 (82%) cases of precursor B-ALL. An oligoclonal or a biclonal rearrangement pattern was detected in 15 (30%) of the cases. The IGHV3 subgroup was predominantly used in 25/50 (50%) cases, followed by IGHV1 (14/50, 28%), IGHV4 (9/50, 18%), IGHV2 (5/50, 10%), IGHV6 (4/50, 8%), and IGHV5 (3/50, 6%) (Table 2). Examples of homoduplex and heteroduplex bands of IGH rearrangements are illustrated in Fig. 2. The expected product size of the IGH gene rearrangements are various due to the addition or trimming of nucleotides at the V-D-J junction.

The frequencies of IGHV5 (3%) and IGHV6 (3%) gene usage were lower in children compared to those of AYA (12.5% and 18.7%, respectively). Conversely, the IGHV4 gene rearrangement was more frequent in children than AYA (23.5% vs. 6.2%, respectively). However, the differences were not statistically significant due to the low number of samples.

Owing to the limited availability of patient samples, sequencing was performed with 20 randomly selected samples for analysis of IGHD and IGHJ gene rearrangements. The V-D-J junction revealed the usage of the IGHD2 gene in 8 (40%) and the IGHD3 gene in 5 (25%) clones. The IGHD6, IGHD5, and IGHD2 gene were used in 4, 2, and 1 (20%, 10%, and 5%) clones, respectively. Usages of the IGHD4 and IGHD7 genes were not detected in these rearranged samples. Among the IGHJ gene segments, the most frequently used gene was IGHJ6, which was used in 9 (45%) clones; IGHJ4 was used in 6 (30%) clones, IGHJ5 was used in 3 (15%) clones, and IGHJ1 was used in 2 (10%) clones. The IGHJ2 and IGHJ3 genes were not used in these rearranged sequences. The results are presented in Table 3.

The “N” region sequence of IGH gene rearrangements ranged from 0 nucleotide (nt) to 54 nt, with an average of 10.5 nt. The average size of the N1 region (N nucleotides at the V-D junction) was 7.4 nt, and that of the N2 region (N nucleotides at the D-J junction) was 13.7 nt. In 6 of 20 (30%) IGH rearranged sequences, CDR3 was productive (in-frame without a stop codon), but in 14 of 20 (70%) rearrangements, CDR3 was unproductive (out of frame due to frame shifts and/or stop codons). Somatic mutations in VDJ rearranged sequences were detected at a low frequency. Among the 20 IGH rearranged sequences, at least one or more Vmut/Dmut/Jmut were detected in 14 sequences. On an average, Vmut, Dmut, and Jmut were detected in 0.1, 1.1 and 0.2 nt, respectively.

The aim of this study was to characterize the pattern of IGH gene rearrangements and identify age-associated patterns in South Indian patients with precursor B-ALL. A previous Indian study using Southern blot reported that 98.6% of precursor B-ALL patients had IGH gene rearrangements [13]. However, this study showed lower frequency (82%) of IGH gene rearrangements and the difference was attributed to partial D-J rearrangements only detected in Southern blot (using probes designed for JH genes) method [10].

In this study, IGHV3 were the most frequently utilized genes in precursor B-ALL patients, followed by IGHV1, IGHV4, IGHV2, IGHV6, and IGHV5, in accordance with previous study [14]. The relative use of IGHV4 were higher in children than in young adults, and the use of the IGHV6 subgroup was detected in 8% of our precursor B-ALL cases (including one case of infant pro-B ALL) in spite of its rare usage in normal peripheral B-lymphocytes (0.8%). The IGHV6 subgroup was identified as a component of the quite restricted human fetal antibody repertoire, and increased in infant ALL [15].

The IGHD2, IGHD3, and IGHD6 genes were over-represented, and the IGHD4, IGHD7, and IGHD1 genes were under-represented in our study of precursor B-ALL cases. According to previous studies, the IGHD2 and IGHD3 genes are preferentially utilized and IGHD7 is rare (<1%) in CDR3 of normal and malignant B-cells and B-cell precursors [1617]. However, the rearrangement of the IGHD7 gene is predominant (−40%) in fetal B lineage cells [18], indicating that the IGHD7 gene is preferentially rearranged in the early stages of B-cell development.

The sequencing results demonstrate (Table 3) the predominant usage of the most downstream JH gene (IGJH6) in 45% of clonal IGH gene rearrangements, and the usage of JH genes presented the order IGHJ6>IGHJ4>IGHJ5>IGHJ1. There results corroborate those from a study that showed the predominant usage of the IGHJ6 gene in 60% of the junctions, followed by IGHJ4 and IGHJ5 [10]. However, some previous reports have identified the usage of IGHJ in the order of IGHJ4, IGHJ6, and IGHJ5 [141516]. The frequencies of the IGHJ6, IGHJ4, IGHJ5, and IGHJ2 genes in our study were comparable to those of human BM precursor B-cells reported in the literature [1718]. However, a slightly higher frequency of IGHJ1 and the complete absence of the IGHJ3 gene were observed in our study.

Oligoclonality of IGH gene rearrangements was identified in 30% of our B-ALL cases. Beishuizen et al. [19] reported multiple IGH genes in 30% to 40% of precursor B-ALL cases. Oligoclonal or multiple IGH rearrangements are caused by continuing rearrangement processes (e.g., IGH V to D-J joining) as well as secondary rearrangements (e.g., D-J replacements, IGHV replacements), which result in one or more subclones [2021].

CDR3 sequences were in-frame and hence resulted in the production of heavy chain immunoglobulin in 30% of clonally rearranged sequences in precursor B-ALL cases. However, our study results differed from previous reports, which have shown that 40% and 21% of IGH rearrangements result in productive rearrangements [1420]. However, our results correlate with a study of 108 IGH sequences from 80 children with precursor B-ALL, which revealed that 75.3% of them were unproductive [22].

Somatic mutations in the CDR3 gene were analyzed with IMGT/JunctionAnalysis, which provides the number of mutations in the 3′V-REGION (Vmut), D-REGION (Dmut), and 5′J-REGION (Jmut). Among the 20 IGH rearranged sequences studied, a somatic mutation was detected in 14 sequences. On average, Vmut was detected in 0.1 nt, Dmut was detected in 1.1 nt, and Jmut was detected in 0.2 nt. Somatic mutations are a characteristic feature of mature B cells. Somatic mutations are often detected in follicular lymphomas [23]. Nevertheless, our results are comparable with those of Kiyoi et al. [24], who reported that somatic mutations of IGHD genes (0.97%) and IGHJ genes (0.94%) were rare.

Gawad et al. [25] highlighted the clonal evolution in childhood B-ALL patients, using next-generation sequencing technology, and even identified up to 4024 “evolved” IGH clonotypes per patient. Although the techniques such as Southern blotting and heteroduplex analysis have been used as gold-standard methods for the detection of clonal gene rearrangements, recent technologies such as next-generation sequencing and analysis of next-generation sequencing data by high-throughput and deep sequencing using IMGT/HighV QUEST analysis [2627] are revolutionizing disease diagnostics for detecting the clonal repertoire of IG and T-cell receptor V-(D)-J sequences and precisely identifying the clonal evolution of the disease at the molecular level.

In conclusion, the IGHV3 gene was frequently used; lower frequencies of IGHV5 and IGHV6 and a higher frequency of IGHV4 were detected in children compared with that in AYA. The IGHD2 and IGHD3 genes were over-represented, whereas the IGHD4 and IGHD7 genes were under-represented, and the predominant usage of the IGHJ6 gene was identified in precursor B-ALL patients from South India. In contrast to the TCRG and TCRD gene rearrangements in T-ALL and precursor B-ALL [828], the IGH gene rearrangements in precursor B-ALL did not show any significant age-associated genotype pattern in our population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank the Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India, for funding the project and acknowledge the Lady Tata Memorial Trust, Mumbai, for the award of the Senior Research Scholarship to N.S.

Notes

References

2. Stankovic T, Weston V, McConville CM, et al. Clonal diversity of Ig and T-cell receptor gene rearrangements in childhood B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000; 36:213–224. PMID: 10674894.

3. Matsuda F, Ishii K, Bourvagnet P, et al. The complete nucleotide sequence of the human immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region locus. J Exp Med. 1998; 188:2151–2162. PMID: 9841928.

4. Kabat EA. Antibody complementarity and antibody structure. J Immunol. 1988; 141:S25–S36. PMID: 3049810.

5. Lefranc MP, Lefranc G. The immunoglobulin factsbook. London, UK: Academic Press;2001. p. 1–458.

6. Giudicelli V, Lefranc MP. IMGT/junctionanalysis: IMGT standardized analysis of the V-J and V-D-J junctions of the rearranged immunoglobulins (IG) and T cell receptors (TR). Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011; 2011:716–725. PMID: 21632777.

7. Alt FW, Yancopoulos GD, Blackwell TK, et al. Ordered rearrangement of immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region segments. EMBO J. 1984; 3:1209–1219. PMID: 6086308.

8. Sudhakar N, Nancy NK, Rajalekshmy KR, Ramanan G, Rajkumar T. T-cell receptor gamma and delta gene rearrangements and junctional region characteristics in south Indian patients with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2007; 82:215–221. PMID: 17133429.

9. Magrath I, Shanta V, Advani S, et al. Treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in countries with limited resources; lessons from use of a single protocol in India over a twenty year period. Eur J Cancer. 2005; 41:1570–1583. PMID: 16026693.

10. Szczepański T, Willemse MJ, van Wering ER, van Weerden JF, Kamps WA, van Dongen JJ. Precursor-B-ALL with D(H)-J(H) gene rearrangements have an immature immunogenotype with a high frequency of oligoclonality and hyperdiploidy of chromosome 14. Leukemia. 2001; 15:1415–1423. PMID: 11516102.

11. Langerak AW, Szczepański T, van der Burg M, Wolvers-Tettero IL, van Dongen JJ. Heteroduplex PCR analysis of rearranged T cell receptor genes for clonality assessment in suspect T cell proliferations. Leukemia. 1997; 11:2192–2199. PMID: 9447840.

12. Brochet X, Lefranc MP, Giudicelli V. IMGT/V-QUEST: the highly customized and integrated system for IG and TR standardized V-J and V-D-J sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008; 36:W503–W508. PMID: 18503082.

13. Sazawal S, Bhatia K, Gurbuxani S, et al. Pattern of immunoglobulin (Ig) and T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangements in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in India. Leuk Res. 2000; 24:575–582. PMID: 10867131.

14. Li A, Rue M, Zhou J, et al. Utilization of Ig heavy chain variable, diversity, and joining gene segments in children with B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia: implications for the mechanisms of VDJ recombination and for pathogenesis. Blood. 2004; 103:4602–4609. PMID: 15010366.

15. Schroeder HW Jr, Wang JY. Preferential utilization of conserved immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene segments during human fetal life. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990; 87:6146–6150. PMID: 2117273.

16. Yamada M, Wasserman R, Reichard BA, Shane S, Caton AJ, Rovera G. Preferential utilization of specific immunoglobulin heavy chain diversity and joining segments in adult human peripheral blood B lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1991; 173:395–407. PMID: 1899102.

17. Wasserman R, Ito Y, Galili N, et al. The pattern of joining (JH) gene usage in the human IgH chain is established predominantly at the B precursor cell stage. J Immunol. 1992; 149:511–516. PMID: 1624797.

18. Schroeder HW Jr, Mortari F, Shiokawa S, Kirkham PM, Elgavish RA, Bertrand FE 3rd. Developmental regulation of the human antibody repertoire. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995; 764:242–260. PMID: 7486531.

19. Beishuizen A, Hahlen K, Hagemeijer A, et al. Multiple rearranged immunoglobulin genes in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia of precursor B-cell origin. Leukemia. 1991; 5:657–667. PMID: 1909409.

20. Wasserman R, Yamada M, Ito Y, et al. VH gene rearrangement events can modify the immunoglobulin heavy chain during progression of B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1992; 79:223–228. PMID: 1728310.

21. Steenbergen EJ, Verhagen OJ, van Leeuwen EF, von dem Borne AE, van der Schoot CE. Distinct ongoing Ig heavy chain rearrangement processes in childhood B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1993; 82:581–589. PMID: 8329713.

22. Katsibardi K, Braoudaki M, Papathanasiou C, Karamolegou K, Tzortzatou-Stathopoulou F. Clinical significance of productive immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangements in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011; 52:1751–1757. PMID: 21649543.

23. Levy S, Mendel E, Kon S, Avnur Z, Levy R. Mutational hot spots in Ig V region genes of human follicular lymphomas. J Exp Med. 1988; 168:475–489. PMID: 3045247.

24. Kiyoi H, Naoe T, Horibe K, Ohno R. Characterization of the immunoglobulin heavy chain complementarity determining region (CDR)-III sequences from human B cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. J Clin Invest. 1992; 89:739–746. PMID: 1541668.

25. Gawad C, Pepin F, Carlton VE, et al. Massive evolution of the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus in children with B precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2012; 120:4407–4417. PMID: 22932801.

26. Li S, Lefranc MP, Miles JJ, et al. IMGT/HighV QUEST paradigm for T cell receptor IMGT clonotype diversity and next generation repertoire immunoprofiling. Nat Commun. 2013; 4:2333. PMID: 23995877.

27. Gazzola A, Mannu C, Rossi M, et al. The evolution of clonality testing in the diagnosis and monitoring of hematological malignancies. Ther Adv Hematol. 2014; 5:35–47. PMID: 24688753.

28. Sudhakar N, Nancy NK, Rajalekshmy KR, Rajkumar T. Diversity of T-cell receptor gene rearrangements in South Indian patients with common acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Iran J Immunol. 2009; 6:141–146. PMID: 19801787.

Fig. 2

Heteroduplex analysis of IGH gene rearrangements in precursor-B-ALL. (A) Homoduplex bands (size 310 bp) and heteroduplex bands of IGHV1-IGHJ are distinguished in lanes 1 to 4. M- Molecular weight marker. (B) Homoduplex bands (size 350 bp) and a smear of heteroduplex bands of IGHV2-IGHJ. (C) Homoduplex (size 300 bp) and heteroduplex bands of IGHV3-IGHJ. (D) Homoduplex (size 304 bp) and heteroduplex bands of IGHV4-IGHJ. (E) Homoduplex bands (size 340 bp) and a smear of heteroduplex for IGHV5-IGHJ; lane 3-a homoduplex band (size 356 bp) and a smear of heteroduplex for IGHV6-IGHJ rearrangement are shown.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download