Abstract

Background

Patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) often have concurrent aplastic anemia (AA). This study aimed to determine whether eculizumab-treated patients show clinical benefit regardless of concurrent AA.

Methods

We analyzed 46 PNH patients ≥18 years of age who were diagnosed by flow cytometry and treated with eculizumab for more than 6 months in the prospective Korean PNH registry. Patients were categorized into two groups: PNH patients with concurrent AA (PNH/AA, N=27) and without AA (classic PNH, N=19). Biochemical indicators of intravascular hemolysis, hematological laboratory values, transfusion requirement, and PNH-associated complications were assessed at baseline and every 6 months after initiation of eculizumab treatment.

Results

The median patient age was 46 years and median duration of eculizumab treatment was 34 months. Treatment with eculizumab induced rapid inhibition of hemolysis. At 6-month follow-up, LDH decreased to near normal levels in all patients; this effect was maintained until the 36-month follow-up regardless of concurrent AA. Transfusion independence was achieved by 53.3% of patients within the first 6 months of treatment and by 90.9% after 36 months of treatment. The mean number of RBC units transfused was significantly reduced, from 8.5 units during the 6 months prior to initiation of eculizumab to 1.6 units in the first 6 months of treatment, for the total study population; this effect was similar in both PNH/AA and classic PNH.

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is an acquired hematopoietic stem cell disease characterized by the intravascular lysis of red blood cells (RBCs), thromboembolism (TE), and bone marrow failure [1]. Aplastic anemia (AA) is the most frequently associated bone marrow failure syndrome in PNH, and it has been reported that a history of severe AA is present in at least one-half of all newly diagnosed PNH cases [2]. Eculizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds specifically to human complement protein C5 and inhibits the formation of the terminal complement complex, has been used to prevent hemolysis associated with PNH. Long-term safety and efficacy data of eculizumab for 195 patients with PNH have been reported by Hillmen et al. [3]; however, data on Asian patients are scarce because of the recent availability of eculizumab to the region. In Korea, medical insurance reimbursement of eculizumab began in 2012 for PNH patients with complications such as TE, pulmonary hypertension, or chronic kidney disease (CKD). The Korean government reimbursement criteria of eculizumab in PNH are complex: all patients receiving eculizumab in Korea not only must have elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, but also have at least one complication before eculizumab treatment. The aim of this study was to evaluate clinical outcomes with eculizumab in Korean patients with PNH concurrent with AA (PNH/AA) and without AA (classic PNH).

Patients ≥18 years of age with PNH diagnosed by flow cytometry and treated with eculizumab for more than 6 months were analyzed in this prospective PNH registry study. Patients were categorized into two groups. Patients with concurrent AA or a history of AA were classified as PNH/AA; those without concurrent disease were categorized as classic PNH [4]. Patients with severe AA (i.e., absolute neutrophil count (ANC) <0.5×109/L, platelets <20×109/L, and bone marrow cellularity <20%) and those who had received eculizumab treatment for less than 6 months were excluded. Biochemical indicators of intravascular hemolysis and hematological laboratory values including LDH, hemoglobin, platelet, ANC, reticulocyte count, PNH clones (granulocytes and/or erythrocytes), serum creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) were assessed at the time of eculizumab initiation and at least every 6 months thereafter. Transfusion requirement, history and/or presence of clinical features including thrombosis, renal failure, pulmonary hypertension, smooth muscle spasm (defined as severe/recurrent abdominal pain requiring opioids), and symptoms (chest pain, dyspnea, abdominal pain, dysphagia, erectile dysfunction, and hemoglobinuria) were also assessed by the treating physician at baseline and every 6 months after initiation of eculizumab treatment. We collected and analyzed the data prospectively. This study was approved by the institutional review board of all participating hospitals, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

All patients were vaccinated against Neisseria meningitidis at least 2 weeks prior to starting eculizumab. Eculizumab was administered at a weekly dose of 600 mg by intravenous infusion from weeks 1 to 4, followed by infusion of 900 mg at week 5, and then 900 mg biweekly for an indefinite period.

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Differences between the two groups (classic PNH vs. PNH/AA) were compared using the Student t-test, chi-squared test, or Mann–Whitney U test. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to assess changes from baseline to specific time points for LDH, hemoglobin, and number of units of transfused packed RBCs. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

As of December 2016, a total of 46 patients were enrolled who met the inclusion criteria, of which 19 patients (41%) were categorized in the classic PNH group and 27 patients (59%) in the PNH/AA group. Among the 27 patients in the PNH/AA group, 20 had a history of AA and 7 patients had AA concurrent with PNH at the time of initiation of eculizumab. The median age of the study population was 46 years (range, 18–73 yr) at eculizumab initiation, and the median duration of eculizumab treatment was 34 months (range, 6–44 mo). Median LDH fold×upper limit of normal (ULN) was 7.3 (range, 2.4–23.7) and GPI-deficient granulocytes was 92.8% (range, 15.7–100%) at the time of eculizumab treatment.

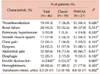

Table 1 shows the characteristics and baseline laboratory findings of each group. Median age, gender ratio, disease duration, duration of eculizumab treatment, and laboratory parameters such as LDH, hemoglobin, platelets, reticulocytes, creatinine, and PNH clone size were similar between the two groups, except for ANC count (Table 1). Baseline clinical manifestations are described in Table 2. The most common finding was hemoglobinuria (82.6%) followed by abdominal pain (69.6%), dyspnea (52.2%), renal failure (43.5%), and TE (41.3%). The mean number of RBC transfusion units was 8.5 (range, 0–37) during the 6 months prior to eculizumab treatment and there was no difference between the two groups (Table 2).

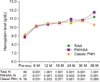

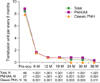

Treatment with eculizumab induced rapid inhibition of hemolysis. At 6 months post-initiation of eculizumab, LDH decreased to near normal levels in all patients, and this effect was maintained until the 36-month follow-up (Fig. 1). As inhibition of hemolysis was maintained, anemia was also improved. At 6 months after initiation of eculizumab, hemoglobin levels were significantly increased as compared with prior to the initiation of eculizumab, and the effect (hemoglobin above 10 g/dL) was sustained at 36 months. Both PNH/AA and classic PNH patients showed similar improvement of anemia (Fig. 2). Next, we analyzed transfusion requirement. The mean number of packed RBC units transfused was significantly reduced, from 8.5 units during the 6 months prior to initiation of eculizumab to 1.6 units in the first 6 months of treatment with eculizumab, for the total study population; this effect was similar in both the PNH/AA and classic PNH groups (Fig. 3). At 36-month follow-up, the mean number of transfused RBC units for the PNH/AA group was 0.3 and 0 for the classic PNH group. Overall, transfusion independence in the study population was achieved by 53.3% within the first 6 months of treatment and by 90.9% after 36 months of treatment.

As shown in Table 3, a total 19 patients had a history of TE before eculizumab treatment, and 10 of 19 (52.6%) used anticoagulation therapy (4 in the classic PNH and 6 in the PNH/AA group). During the eculizumab treatment period, 6 patients (3 in each group) were under anticoagulation therapy. Among them, 3 patients discontinued anticoagulation following the resolution of TE, and 3 patients continued to receive anticoagulation agents with resolution of TE. During the study period, only 1 patient with classic PNH who stopped anticoagulation after complete resolution of TE experienced recurrent TE at the same sites (deep vein and pulmonary artery). This patient restarted anticoagulation therapy at the 36-month follow-up.

Nine patients had baseline eGFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, of which 5 patients (56%) showed improvement of eGFR during eculizumab treatment and 4 patients had stabilized eGFR. No patients developed worsening of renal function.

Among patients with a history of pulmonary hypertension and smooth muscle spasm, none developed new or recurrent symptoms or signs during the eculizumab treatment period.

Clinical symptoms and signs were significantly improved in the overall study population. Among 32 patients who had abdominal pain, 3 patients reported abdominal pain after eculizumab treatment (2 in the classic PNH group and 1 in the PNH/AA group). Among 38 patients with hemoglobinuria and 24 with dyspnea, only 1 patient in each group reported symptoms of these conditions after eculizumab treatment. Among 6 male patients with erectile dysfunction, 1 patient with classic PNH reported the condition after eculizumab treatment. None of the patients who had previously reported chest pain or dysphagia (12 patients each) complained of such symptoms after eculizumab treatment.

To better understand the impact of reducing intravascular hemolysis, we analyzed data from the prospective Korean PNH registry. We evaluated the hemolysis, anemia parameter, transfusion requirement, PNH-related symptoms and complications for PNH patients with or without AA who received eculizumab. We hypothesized that all patients treated with eculizumab would show clinical benefits and that eculizumab treatment could thus reduce the risk of progressive complications such as TE, pulmonary hypertension, and renal failure, regardless of concurrent disorders. As found in this analysis, eculizumab treatment showed rapid and sustained reduction of hemolysis in all patients with PNH through 36 months of follow-up. Decreased hemolysis resulted in the improvement of anemia regardless of a concurrent disorder, and transfusion independence was achieved in 90.9% of patients after 36 months of treatment. Hemoglobin stabilization and reduced transfusion requirements with eculizumab have been described in several studies [5678], and we confirmed that those effects were achieved regardless of underlying AA. By reducing intravascular hemolysis, we also observed that abdominal pain, dysphagia, and erectile dysfunction were improved after eculizumab treatment.

We previously reported that the prevalence of TE was 18% in 301 Korean patients with PNH who had not received eculizumab, and this was associated with increased risk for mortality [9]. In this study, a total of 19 patients reported a history of TE at the time of initiation of eculizumab and 6 had received concomitant anticoagulation therapy. All enrolled patients with TE had resolution of TE. However, 1 patient with classic PNH had recurrence of TE at the same sites after discontinuing anticoagulation therapy while on eculizumab. This result is similar to that of a previous study reporting that 96.4% of patients remained free of TE [3].

Renal dysfunction has been well reported in PNH [10] and several studies have consistently shown that eculizumab has a protective role in renal function [311]. In our study, we enrolled 9 patients who had baseline eGFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Among these, 5 patients (56%) showed improvement of eGFR during eculizumab treatment and 4 patients had stabilized eGFR. Because TE and renal impairment are known independent risk factors for mortality in Korean PNH patients [12], the effects of eculizumab on these risk factors is expected to improve patient survival.

Owing to the relatively recent introduction and approval of eculizumab, long-term clinical data are not yet available, and data from Asian countries are scarce [10]. The first study reporting the efficacy of eculizumab among Asian patients with PNH was the AEGIS study from Japan [8]. This trial was an open-label, non-comparative, multicenter phase II study including 27 patients. Interestingly, the authors compared the effect of eculizumab between PNH patients (N=15) and patients with PNH plus AA/myelodysplastic syndrome (N=12) and found that there was no difference between the two groups in terms of hemolysis, blood transfusion, and fatigue score [8]. Our data revealed similar findings, providing additional evidence for the role of eculizumab in PNH/AA.

In conclusion, clinical outcomes with eculizumab were significantly improved compared with the baseline in both patients with PNH/AA and those with classic PNH. This study demonstrated that eculizumab has a beneficial role in the management of patients with PNH/AA, similar to that of classic PNH, by inhibiting hemolysis and reducing transfusion requirements, thus resulting in the improvement of clinical signs and symptoms.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Reduction in hemolysis after eculizumab. Treatment with eculizumab induced rapid and consistent inhibition of hemolysis to near normal levels in all patients after 36 months of follow-up. Patients with both PNH/AA and classic PNH had significant median change of LDH level. P-values compared with baseline were assessed using Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Abbreviations: AA, aplastic anemia; ecu, eculizumab; PNH, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Fig. 2

Improvement of anemia after eculizumab. In both patients with PNH/AA and classic PNH, hemoglobin levels were significantly improved after the first 6 months of eculizumab treatment; the effect (hemoglobin above 10 g/dL) was sustained after 36 months. P-values compared with baseline were assessed by Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Abbreviations: AA, aplastic anemia; ecu, eculizumab; PNH, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

Fig. 3

Reduction of transfusion requirement after eculizumab. The mean number of packed RBC units transfused was significantly reduced from 8.5 units during the 6 months prior to initiation of eculizumab to 1.6 units in the first 6 months of treatment, for the total study population. P-values compared with baseline were assessed by Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Abbreviations: AA, aplastic anemia; ecu, eculizumab; PNH, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; RBC, red blood cells.

References

1. Hillmen P, Lewis SM, Bessler M, Luzzatto L, Dacie JV. Natural history of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N Engl J Med. 1995; 333:1253–1258.

2. Schrezenmeier H, Muus P, Socié G, et al. Baseline characteristics and disease burden in patients in the International Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria Registry. Haematologica. 2014; 99:922–929.

3. Hillmen P, Muus P, Röth A, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of sustained eculizumab treatment in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Br J Haematol. 2013; 162:62–73.

4. Parker C, Omine M, Richards S, et al. Diagnosis and management of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2005; 106:3699–3709.

5. Kelly RJ, Hill A, Arnold LM, et al. Long-term treatment with eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: sustained efficacy and improved survival. Blood. 2011; 117:6786–6792.

6. Hillmen P, Young NS, Schubert J, et al. The complement inhibitor eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:1233–1243.

7. Brodsky RA, Young NS, Antonioli E, et al. Multicenter phase 3 study of the complement inhibitor eculizumab for the treatment of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2008; 111:1840–1847.

8. Kanakura Y, Ohyashiki K, Shichishima T, et al. Safety and efficacy of the terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in Japanese patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: the AEGIS clinical trial. Int J Hematol. 2011; 93:36–46.

9. Lee JW, Jang JH, Kim JS, et al. Clinical signs and symptoms associated with increased risk for thrombosis in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria from a Korean Registry. Int J Hematol. 2013; 97:749–757.

10. Al-Ani F, Chin-Yee I, Lazo-Langner A. Eculizumab in the management of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: patient selection and special considerations. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016; 12:1161–1170.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download