INTRODUCTION

Hemoglobin D-Iran (Hb D-Iran) (

HBB: c.67G>C) is a rare Hb variant first reported in a family from central part of Iran in 1973 by Rahbar [

1]. It occurs due to a mutation in codon 22 of the β-globin gene involving a transversion of GAA to CAA leading to a substitution of glutamate by glutamine. For detection of the structural variants of Hb and estimation of Hb A2 and Hb F levels, cation exchange-high performance liquid chromatography technique (CE-HPLC) is employed most frequently [

2]. Hb D-Iran is eluted in the Hb A2 window on the β-thalassemia short program on the Biorad Variant II CE-HPLC equipment [

3]. In India, the most common structural variant that is also eluted in the Hb A2 window is Hb E [

4]. Hb E (

HBB: c.79G>A) is a common structural variant reported in eastern and northern India and occurs due to a G to A substitution in codon 26 of the β-globin chain [

5]. Although Hb D-Iran is commonly described in Iran, its prevalence in India is largely unknown. In a series of CE-HPLC records on 2,600 patients, only 1 case of Hb D-Iran (0.038%) was reported [

6], while in a second series of records on 800 patients, 3 cases of Hb D-Iran (0.375%) were reported [

4]. Additionally, Hb E has been reported in about 0.26% [

6] and 2.5% [

4] of patients undergoing CE-HPLCs in north India. Ideally for the identification of abnormal Hb, two techniques based on two different principles are required [

7].

Based on this, we aimed to study all CE-HPLC records during 2009–2013 to select variants eluting >9% in the Hb A2 window and determine the proportion of patients with Hb D-Iran. Furthermore, we compared the differences in the red cell indices and the peak characteristics between patients with Hb D-Iran and those with Hb E using CE-HPLC.

Go to :

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective study performed at Department of Hematology, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi, which caters to patients primarily from north India. Generally, we employ two techniques to detect Hb variants. All cases are initially subjected to CE-HPLC, which is performed using the variant β-thalassemia short program on the Bio-Rad Variant II, HE10 system. In cases where an abnormal Hb variant is detected on CE-HPLC, alkaline and acid electrophoresis is performed on SAS1 (Helena Biosciences, United Kingdom) to confirm the findings. Automated peripheral blood counts were available in all the cases (LH750 and DxH, Beckman Coulter Inc., Miami, FL, USA).

CE-HPLC records over a 5-yr period between January 1st, 2009 and December 31st, 2013 were retrieved. These results were screened for peaks >9% in the Hb A2 window. Cases of Hb Lepore were excluded based on peak characteristics in CE-HPLC results and alkaline electrophoretic mobility. This was done to select all cases of Hb D-Iran and Hb E as a cause of elevated Hb A2. Based on the CE-HPLC and electrophoresis findings, cases were sub-divided into those of Hb D-Iran and Hb E. A comparison of red cell indices, and A2 peak retention time and area was performed between heterozygous Hb D-Iran and heterozygous Hb E using descriptive statistics and student's t-test. P-value<0.05 was considered significant.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

CE-HPLC is the most commonly employed technique for the diagnosis of hemoglobinopathies. β-thalassemia short program is a routinely used diagnostic CE-HPLC program that splits Hb into various peaks, which elute in various windows, depending on the retention time. In addition to Hb A2, multiple Hbs, such as Hb E, Hb D-Iran, Hb Lepore, Hb G-Honolulu, Hb Osu-Christiansborg, and Hb Korle-Bu elute in the Hb A2 window [

8].

Of these variants, Hb E is prevalent in the north-eastern states [

910]. The largest series of >90,000 CE-HPLC records from West Bengal has revealed heterozygous Hb E in 2.68%, Eβ in 1.56%, and Hb E in 0.39% individuals who underwent thalassemia screening [

10]. This paper reports a higher incidence of Hb E as the patient population was from eastern India. In this series, there was no patient with Hb D-Iran as this variant is largely reported from north-western India. However, only a few cases of Hb D-Iran have been reported from India [

46]. On the contrary, Hb D-Iran has been commonly described in Iran. In an 8-year analysis in Fars province in Iran, Hb D was the most frequent Hb variant after α- and β-thalassemia. Interestingly, of the 180 carriers with Hb D-variant, Hb D-Punjab and Hb D-Iran were almost equally reported [

11]. The prevalence of Hb D-Iran in India is largely restricted to isolated case reports [

1213] or a few cases in large case series [

46]. A large series of 2,600 cases was retrieved for detection of Hb variants and hemoglobinopathies in Indian population, which showed only a single case of Hb D-Iran (0.038%) [

6]. Another study was conducted at AIIMS in 2008, where they tested 800 samples for over a period of 7 mo and found 3 cases of Hb D-Iran (0.375%) [

4]. Hb D-Iran in India has been reported from the north western region [

10].

In this study on >12,000 CE-HPLC records, the frequency of Hb D-Iran was 0.23%, while that of Hb E was 1.56%. The frequency of Hb D-Iran was similar to that reported by Rao et al. [

4] at 0.375%, but a higher number of records enabled us to analyze the differences between heterozygous Hb D-Iran and Hb E. This frequency is lesser than that reported from the second large series from north India [

6] probably because of the fact that we employed two techniques (CE-HPLC, and acid and alkaline electrophoresis) to analyze cases of Hb variants, while Sachdev et al. [

6] reported only the CE-HPLC data.

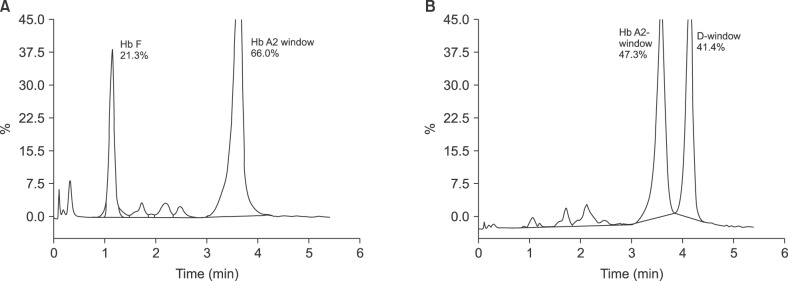

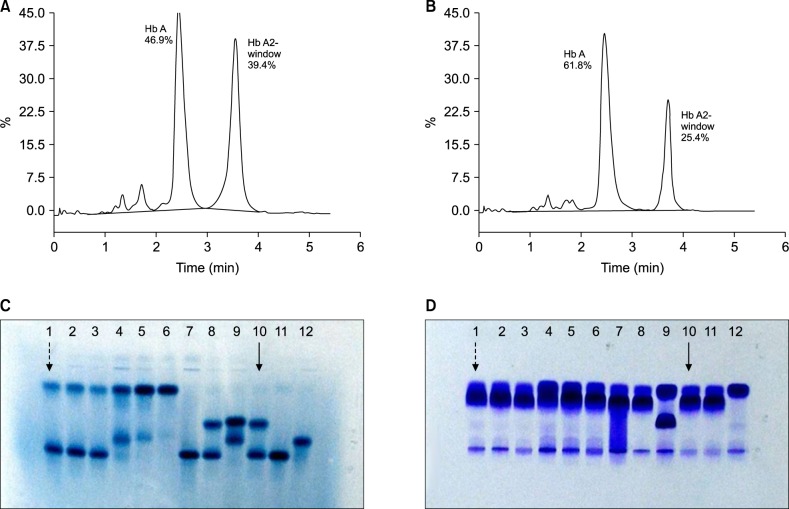

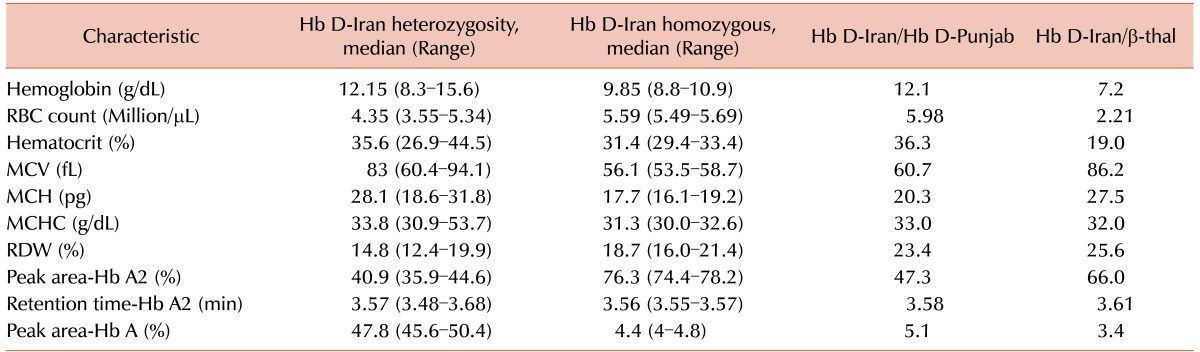

On evaluating the clinical profile of these Hb D-Iran, all cases were asymptomatic, except a case of compound heterozygous Hb D-Iran/β-thalassemia, which showed moderate anemia, fatigue, and weakness. Even though both heterozygous and homozygous Hb D-Iran cases were clinically asymptomatic, they had certain differences in the hematological profile. The patients with heterozygous Hb D-Iran had normal Hb with normocytic normochromic red cell indices, while those with homozygous Hb D-Iran had mild anemia with red cell indices similar to those in thalassemia. The findings for patients with heterozygous Hb D-Iran were similar to those of patients form Iran reported by Zakerinia et al. [

11]. The case of compound heterozygous Hb D-Iran/D-Punjab has been previously published in a case report [

14].

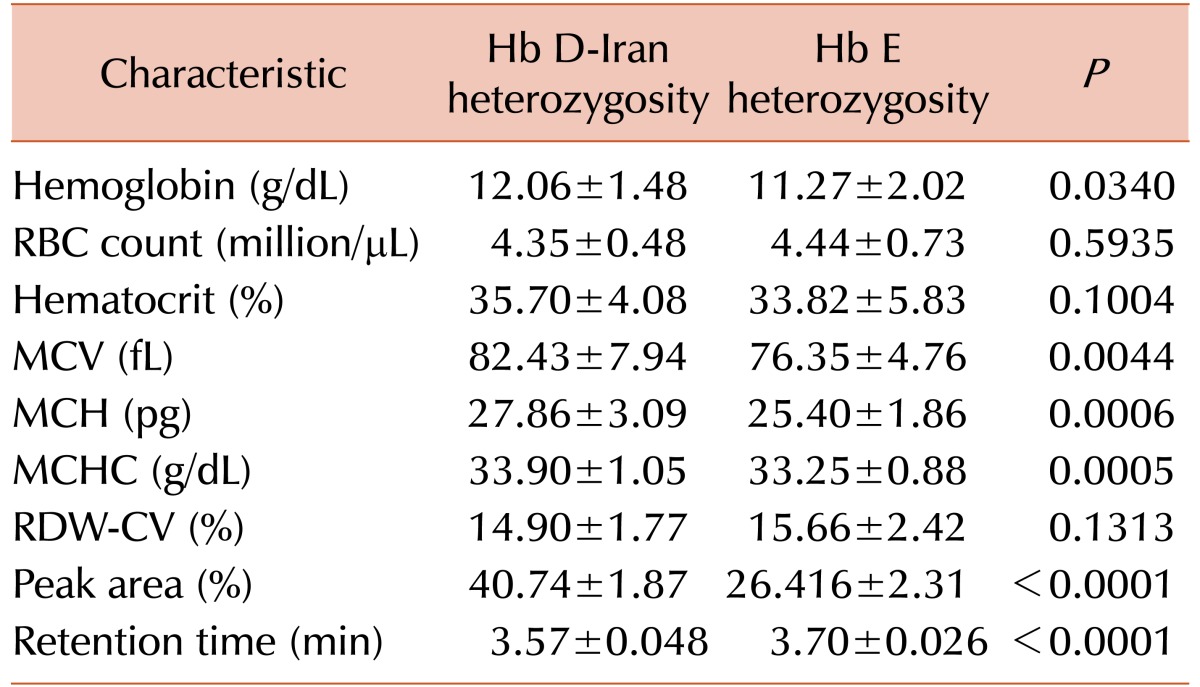

By comparing cases of heterozygous Hb D-Iran and those of Hb E, it was observed that patients with heterozygous Hb D-Iran had a significantly higher Hb, MCV, MCH, and MCHC on hemogram and the mean peak area of the Hb A2 window was 14% higher in CE-HPLC than those of heterozygous Hb E. Retention time of Hb D-Iran was significantly lower than that of Hb E. The mean peak area was 40.9%, which is similar to that reported previously from India [

4]. The retention time of Hb D-Iran in our series was 3.56 min, which was similar to 3.62 min reported by Rao et al. [

4] and 3.49 min reported by Jutovsky et al. [

8]. On the contrary, the peak area for heterozygous Hb E was 26.4% with mean retention time of 3.70 min. These findings are similar to those reported by earlier studies from India [

4]. The differences in peak characteristics and retention time should be sufficient to differentiate between Hb E and Hb D-Iran carriers and the homozygous carriers. However, in some situations where the level of Hb D-Iran may be lower, such as with a concomitant iron deficiency [

11], alkaline electrophoresis is a very informative technique. In alkaline electrophoresis, Hb E moves along with Hb A2, while Hb D-Iran moves with an electrophoretic mobility similar to that of Hb S and Hb D-Punjab [

4].

We did not find any case of compound heterozygous for Hb D-Iran/Hb S. The importance of distinguishing Hb D-Iran from Hb D-Punjab most importantly lies in the cases of compound heterozygous Hb D with Hb S. Compound heterozygous Hb D-Punjab with Hb S produces significant sickling disorder; however, Hb D-Iran with Hb S is clinically benign [

15].

We found that the two techniques—CE-HPLC and alkaline and acid electrophoresis—when used together helped to clearly differentiate between Hb D-Iran from other Hb variants, most importantly Hb D-Punjab and Hb E, in all the cases. In alkaline and acid electrophoresis, Hb D-Iran and Hb D-Punjab are observed at the same position, which can be differentiated on CE-HPLC. Likewise, Hb D-Iran and Hb E are closely eluted on CE-HPLC, which can be easily differentiated at their separate positions in alkaline electrophoresis.

In conclusion, Hb D-Iran elutes in the Hb A2 window of the β-thalassemia short program. Patients with heterozygous Hb D-Iran have no anemia with normocytic indices, unlike patients with heterozygous Hb E, who have red cell indices similar to those of thalassemia. Patients with homozygous Hb D-Iran also have red cell indices similar to those of thalassemia. To distinguish heterozygous Hb D-Iran form Hb E, careful analysis of peak area and retention time should be sufficient in most cases and may be further confirmed using alkali electrophoresis as the second technique.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download