Abstract

Background

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) is an aggressive malignancy with very poor prognosis and short survival, caused by the human T-lymphotropic virus type-1 (HTLV-1). The HTLV-1 biomarkers trans-activator x (TAX) and HTLV-1 basic leucine zipper factor (HBZ) are main oncogenes and life-threatening elements. This study aimed to assess the role of the TAX and HBZ genes and HTLV-1 proviral load (PVL) in the survival of patients with ATLL.

Methods

Forty-three HTLV-1-infected individuals, including 18 asymptomatic carriers (AC) and 25 ATLL patients (ATLL), were evaluated between 2011 and 2015. The mRNA expression of TAX and HBZ and the HTLV-1 PVL were measured by quantitative PCR.

Results

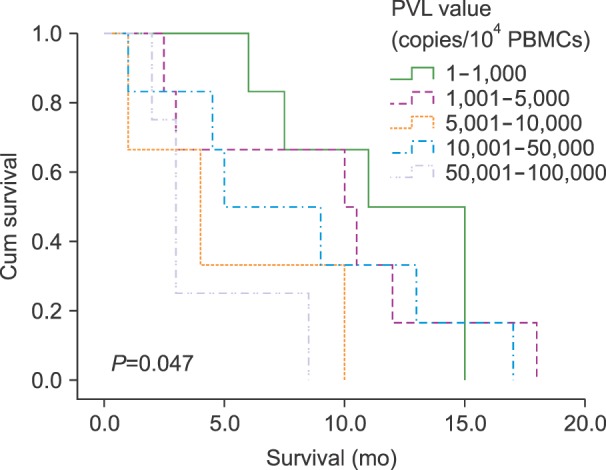

Significant differences in the mean expression levels of TAX and HBZ were observed between the two study groups (ATLL and AC, P=0.014 and P=0.000, respectively). In addition, the ATLL group showed a significantly higher PVL than AC (P=0.000). There was a significant negative relationship between PVL and survival among all study groups (P=0.047).

Conclusion

The HTLV-1 PVL and expression of TAX and HBZ were higher in the ATLL group than in the AC group. Moreover, a higher PVL was associated with shorter survival time among all ATLL subjects. Therefore, measurement of PVL, TAX, and HBZ may be beneficial for monitoring and predicting HTLV-1-infection outcomes, and PVL may be useful for prognosis assessment of ATLL patients. This research demonstrates the possible correlation between these virological markers and survival in ATLL patients.

Go to :

Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is a lentivirus that belongs to the Retroviridae family in the genus Deltaretrovirus [1]. About 20 million infected people live in Africa, the Caribbean, Asia, and Central and South America [2].

The Gag, pro, pol, and env are the main genes of HTLV-1and also contains two long terminal repeat (LTR) regions. These genes encode the viral integrase, reverse transcriptase, and regulatory proteins (e.g., TAX and superficial glycoprotein) [3]. While HTLV-1 can transform and immortalize cells in vitro, only 2–5% of infected individuals go on to develop one of the two major pathogenic conditions, which occurs after a long-term period of dormancy [4]. The two major diseases associated with HTLV-1 infection are the antagonistic CD4+CD25+ T cell malignancy called adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) and a host autoreactive inflammatory disorder called HTLV-1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) [56].

According to the Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) classification and World Health Organization (WHO), ATLL is classified into four subtypes (acute, lymphoma, chronic, and smoldering) based on the following symptoms: the persistence of flower-like cells in peripheral blood smear, elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), hypercalcemia, skin lesions, organomegaly, and lytic bone injury [78]. The most aggressive ATLL types are the acute and lymphoma types. The acute type has the highest prevalence rate (60%) and shortest survival time (4–6 mo) among all ATLL types, and it shows some of the most aggressive symptoms (e.g., hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, a high frequency of atypical lymphocytes with nuclear hypersegmentation, as well as high levels of LDH and calcium in serum). The lymphoma type has a prevalence rate of 20% and a 9–10-month survival period, which demonstrates the aggressiveness of ATLL. The chronic and smoldering types have a survival period of 2–5 years and are less frequently associated with aggressive clinical conditions [29]. The primary infection is followed by a long-term latency period (20–40 yrs). Then, leukemogenesis of infected T-cells occurs in a multistep process via genetic and epigenetic alterations [10].

Although the exact pathogenic mechanism of ATLL is unknown, it is found that clonal expansion of infected T-cells increases the number of viral progeny, leading to plus-strand transcription of the HTLV-1 genome. In addition to the major gene described above, the genome also encodes other factors including accessory genes (open reading frames I and II), regulatory genes (tax and rex), and P12, P13, and P30, which are necessary for viral persistence and infection. These viral regulatory proteins (e.g., TAX and HBZ) are thought to initiate transformation and promote genetic instability and transactivation in this T-cell malignancy [8].

Transactivation of the viral LTR and functional cellular genes is synchronized by TAX; however, TAX does not bind to DNA, but may upregulate the expression of cell survival factors such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1), which function as anti-apoptotic elements [11]. Previous studies have suggested that TAX protein promotes downregulation of the expression of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element-binding protein (CREB) and activating transcription factor (ATF) signaling proteins, as well as DNA repair proteins (e.g., P53 and retinoblastoma [Rb]). Therefore, TAX may play a critical role in malignant T-cell proliferation [1213]. Regarding the TAX antigen structure, a strong immune response in HTLV-1-infected patients can eliminate or suppress TAX expression [14]. However, genetic alteration of HTLV-1 by methylation, deletion, or mutation in the 3' LTR region can lead to low TAX protein expression [15]. These mechanisms may allow ATLL cells to escape detection by the host immune system, enabling latent activation of the HTLV-1 genome [16]. The HBZ gene is preserved in and expressed from the antisense strand of the LTR region in HTLV-1-infected cells, and both HBZ mRNA and protein play pivotal roles in cross-reactions with intracellular proteins such as JunB, c-Jun, JunD, and CREB-2 in the development of ATLL [17]. This study aimed to demonstrate the possible correlation between virological markers (PVL and TAX and HBZ expression) and the survival time of patients with ATLL.

Go to :

A case series study was conducted on 43 HTLV-1-infected individuals in the Departments of Hematology and Oncology of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran, and in Ghaem and Imam Reza Hospitals from July 2011 to November 2015. Patients with suspected ATLL were investigated, and on the basis of symptoms and laboratory test results, 25 patients (12 males and 13 females) were diagnosed with ATLL and placed in the ATLL group. The remaining 18 patients (7 male and 11 female) were considered healthy, asymptomatic HTLV-1-infected carriers, and placed in the control group. HTLV-1 seropositive reactivity was checked for all subjects, and the presence of HTLV-1 was confirmed by conventional PCR. ATLL patients were further divided into four groups: acute, lymphoma, chronic, and smoldering, based on the criteria reported by Shimoyama [18].

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Ficoll density gradient centrifugation (Inno-train, Germany) was performed to sort cells from peripheral blood to isolate PBMCs. Total RNA was extracted from PBMCs, using Tripure isolation reagent (Roche, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Purified RNA was treated with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination. RNA integrity was confirmed by gel electrophoresis.

cDNA was synthesized using random primers and reverse transcriptase (Bioneer, South Korea) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The reaction conditions were 12 cycles of 30 seconds at 24℃, 4 minutes at 44℃, and 30 seconds at 55℃. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was included as a positive control for cDNA synthesis. The GAPDH primers were: forward, 5'-CAAGGTCATCCATGA CAACTTTG-3' and reverse, 5'-GTCCACCACCCTGTTGCT GTAG-3'.

After obtaining the desired sequences for the TAX and HBZ genes from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank, primers and probes were designed using AlleleID version 5.

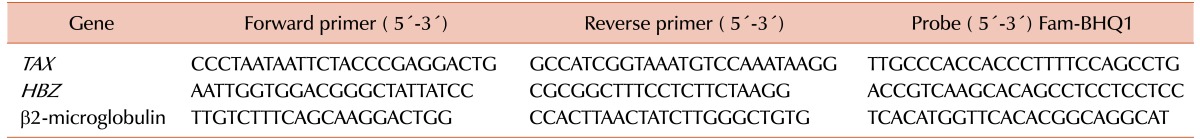

Real-time PCR (TaqMan method) was performed in a Rotor-Gene 6000 cycler (Corbett, Hilden, Germany). Duplicate samples were included in the analysis, and expression is reported relative to that of a housekeeping gene (β2-microglobulin). The primers and probes used to amplify the corresponding genes are shown in Table 1. The PCR conditions were as follows: 95℃ for 4 minutes, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 94℃ for 15 seconds, annealing at the optimum temperature 20 seconds, and extension at 72℃ for 20 seconds.

To evaluate the HTLV-1 PVL, PBMCs were isolated from ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-treated blood samples, as described above under “Isolation of PBMCs and extraction of RNA,” and DNA was extracted from the PBMCs, using a DNA extraction kit. Real-time PCR was performed using a commercial absolute quantification kit (Novin Gene, Iran) to measure the PVL of HTLV-1, using specific primers and a fluorogenic probe. HTLV-1 copy number was reported as the actual amount of cellular DNA quantified, using the albumin gene (ALB) as a reference. There are two copies of ALB in one cell. HTLV-1 and ALB concentrations were calculated from two 5-point standard curves. For normalization, the PVL was calculated as the ratio of HTLV-1 DNA copy number/one-half of the ALB copy number ×104, and is expressed as the number of HTLV-1 proviruses per 104 PBMCs.

Different therapies were administered to the study participants according to the type of disease. The most common first-line treatment for T-cell lymphoma was combination chemotherapy, such as cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP), or cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (CVAD), which was administered to most patients [1920].

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 18, and the results are reported as mean±standard deviation (SD). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was conducted to check variable for normal distribution. The Mann-Whitney U test was performed to analyze the two groups. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was used to determine the relationship between study parameters. Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to evaluate survival. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Go to :

In this study, 25 ATLL patients (13 female and 12 male) and 18 HTLV-1 carriers (11 female and 7 male) were evaluated. The mean age of the subjects in the ATLL group was 53.92±2.17 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 35.42–88.29), while the mean of the carrier group was 38.94±2.04 years (95% CI, 25.13–53.43).

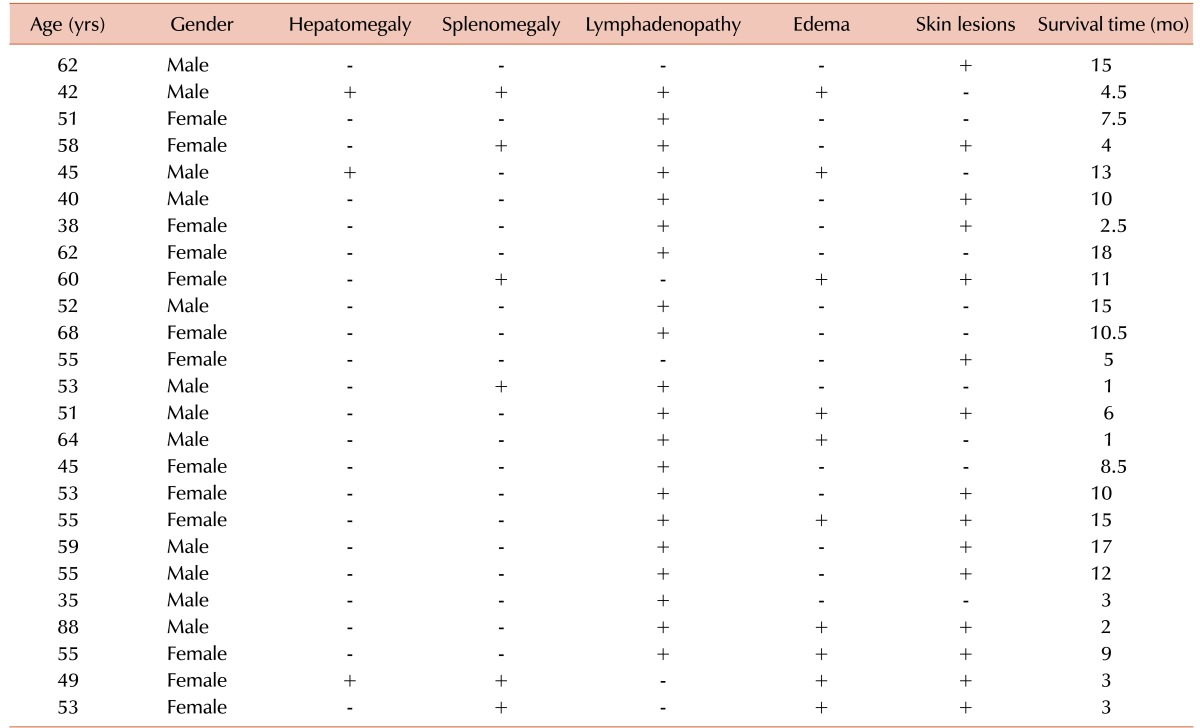

The frequencies of various clinical findings in ATLL patients were as follows: hepatomegaly (12%), splenomegaly (24%), lymphadenopathy (80%), edema (40%), and skin lesions (60%). The ATLL patients were further classified into four subtypes: acute (6), lymphoma (16), chronic (2), and smoldering (1). The mean calcium level was 10.44±0.56 mg/dL (95% CI, 7.23–16.83) in the ATLL group and 9.52±0.34 mg/dL (95% CI, 8.64–10.31) in carriers. Blood calcium levels in the acute, lymphoma, and smoldering groups were 13.13±0.98 (95% CI, 10.24–16.81), 9.14±0.31 (95% CI, 7.45–11.25), and 8.43, respectively. These data showed a significantly higher calcium blood level in patients with acute ATLL than in patients with other types of ATLL (P=0.000).

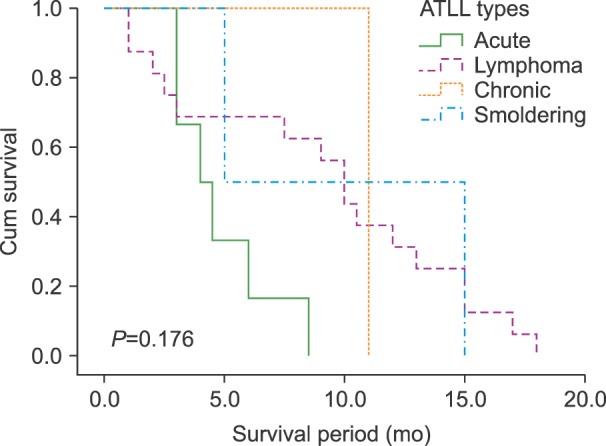

White blood cell (WBC) counts in ATLL patients and carriers were 191,340±6,789 cells/mL (95% CI, 1,200–132,000) and 4,933±392.3 cells/mL (95% CI, 4,400–5,700; P=0.015), respectively. The health of the participants in the carrier group was confirmed by a physician's examination. All the ATLL patients expired during this study, with a median survival time of 8.26±1.05 months (95% CI, 1–18 mo). The mean survival time was 4.83±0.86 months (95% CI, 3–8.5) for the acute group, 9.1±1.44 months (95% CI, 1–18) for the lymphoma group, and 10±5 months (95% CI, 5–15) for the smoldering group. The survival time of the only patient in the chronic group was 11 months. The Kaplan-Meier test results did not show a significant relationship of survival time according to ATLL type (Fig. 1). The clinical symptoms and survival times of the patients are provided in Table 2.

The HTLV-1 PVL was investigated in all 43 study subjects (18 carriers and 25 ATLL patients). The mean HTLV-1 PVL in ATLL patients was 18,100±4,918.9 copies/104 cells (95% CI, 53–91,183), and the percentage of HTLV-1-infected PBMCs in ATLL group was 118±49% (95% CI, 0.5–911). The mean HTLV-1 PVL in the carrier group was 531.23±119.2 copies/104 (95% CI, 2–1,329) in the carrier group, which indicated that 5.3±1.1% (CI: 95% 0.02–13.1) of PBMCs were infected with HTLV-1 (P=0.000).

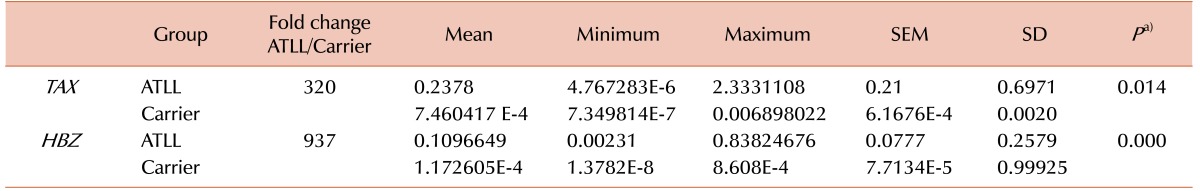

The expression of each gene was divided by the expression of the β2-microglobulin gene to normalize the gene expression values. The mean TAX gene expression level was 0.2378±0.21 (95% CI, 4.7672834E–6–2.3331108) in the ATLL group and 7.460417 E-4±6.1676E-4 (95% CI, 7.349814E–7–0.006898022) in the carrier group (P=0.014). The mean HBZ gene expression level was 0.1096649±0.0777 (95% CI, 0.00231–0.83824676) in the ATLL group and 1.17260526E-4±7.7134E-5 (95% CI, 1.3782E-8–8.608E-4) in the carrier group (P=0.000; Table 3).

A significant correlation was observed between the HTLV-1 PVL and HBZ gene expression, improving the persistence and constant presentation among ATLL patients (r=0.479, P=0.001). Furthermore, a direct positive correlation was found between HBZ gene expression and TAX gene expression (r=0.636, P=0.001), which was intensified by the TAX gene. In contrast, no positive or negative correlation was observed between TAX gene expression and HTLV-1 PVL (r=0.203, P=0.354).

Survival was investigated in all 25 ATLL patients. The variables evaluated in this analysis were age, gender, treatment (such as CHOP or CVAD), and viral gene expression (TAX and HBZ). According to our findings, no significant positive or negative relationship was observed between any of these variables and survival time by Kaplan-Meier analysis. However, the Log Rank test results showed a significant relationship between low PVL and longer survival (P=0.047; Fig. 2).

Go to :

The progression of ATLL is a polyphasic, long-term process, and the outcome of HTLV-1 infection is affected by host-virus interaction as well as cellular division and function [21]. The TAX and HBZ proteins are the two main viral components that interfere with the immune response and cause malignancy [16]. The HTLV-1 TAX and HBZ genes encode highly motivated proteins that disrupt the cell cycle by interfering with apoptosis, DNA repair mechanisms, cell signaling, and control checkpoints and activating transcription factors that regulate cell proliferation [22]. In the present study, we observed higher TAX gene expression in ATLL patients than in the healthy HTLV-1 carriers.

As previously mentioned, ATLL is a multi-step malignancy, and it seems that TAX is used by the virus to initiate disease progression. This process is followed by transactivation of infected T-cells, during which TAX expression can be downregulated by other transcription factors, such as HBZ, to evade the host immune response [5]. Despite the higher TAX gene expression in ATLL patients, there was no direct correlation between TAX gene expression and PVL, which is indicative of the initiating role of this protein.

Constant expression of the HBZ gene might play a pivotal role in the progression of ATLL through activation of anti-apoptotic elements and CREB-dependent cellular proliferation [23]. As HBZ does not contain any immunologically active sites, it can avoid cytotoxic T-cell (CTL) responses in ATLL patients. In the current study, the mean HBZ mRNA level was higher in the ATLL group, and was significantly positively correlated with PVL, which confirmed its essential function in oncogenesis.

Most infected T-cells are resistant to common chemotherapy combinations, and they continue to proliferate, with the exception of cells infected with the HIV retrovirus [2425]. In the present study, the mean WBC count was higher in ATLL patients than in HTLV-1 carriers, which is indicative of aggressive HTLV-1-induced leukemogenesis.

A significant positive correlation was observed between PVL and HBZ mRNA levels, which suggested that HBZ plays a more important role in ATLL cell division, viral replication, or viral assembly than TAX. According to our findings, the progression of ATLL may occur as follows: ATLL is initiated by TAX gene expression, which increases viral replication and TAX protein levels, followed by downregulation of TAX gene expression and upregulation of HBZ gene expression and HTLV-1 PVL in the final stage of ATLL.

Two major life-threatening events occur in ATLL caused by the high levels of blood calcium, which can lead to heart attacks and opportunistic infections [2627]. Hypercalcemia in acute ATLL patients might result from osteolytic bone marrow metastases through hyperactivation of osteoclastogenesis and resorption. It was previously shown that overexpression and secretion of parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) and macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha (MIP-1α) from infected T-cells leads to osteoclast development in bone marrow, resulting in the an osteolytic condition in ATLL patients with high numbers of infected lymphocytes [28].

In this study, a negative relationship was observed between the survival time of ATLL patients and HTLV-1 PVL. This result suggests the prognostic potential of PVL for monitoring ATLL patients. In addition, TAX and HBZ mRNA expression levels, in association with the HTLV-1 PVL, could be used to monitor and predict HTLV-1 infection outcomes.

Go to :

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all the individuals who took part in this study and shared their experiences for the benefit of others. We also extend our gratitude to the authors who contributed to the manuscript and the staff of the departments of Hematology and Oncology at Ghaem and Imam Reza hospitals, for their cooperation in this study.

Go to :

Notes

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Go to :

References

1. Gross C, Thoma-Kress AK. Molecular mechanisms of HTLV-1 cell-to-cell transmission. Viruses. 2016; 8:74. PMID: 27005656.

2. Gonçalves DU, Proietti FA, Ribas JG, et al. Epidemiology, treatment, and prevention of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1-associated diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010; 23:577–589. PMID: 20610824.

3. Christensen AM, Massiah MA, Turner BG, Sundquist WI, Summers MF. Three-dimensional structure of the HTLV-II matrix protein and comparative analysis of matrix proteins from the different classes of pathogenic human retroviruses. J Mol Biol. 1996; 264:1117–1131. PMID: 9000634.

4. Martin JL, Maldonado JO, Mueller JD, Zhang W, Mansky LM. Molecular studies of HTLV-1 replication: An update. Viruses. 2016; 8:pii:E31.

5. Lim AG, Maini PK. HTLV-I infection: a dynamic struggle between viral persistence and host immunity. J Theor Biol. 2014; 352:92–108. PMID: 24583256.

6. Fuzii HT, da Silva Dias GA, de Barros RJ, Falcão LF, Quaresma JA. Immunopathogenesis of HTLV-1-assoaciated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP). Life Sci. 2014; 104:9–14. PMID: 24704970.

7. Cabrera ME, Labra S, Catovsky D, et al. HTLV-I positive adult T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma (ATLL) in Chile. Leukemia. 1994; 8:1763–1767. PMID: 7934173.

8. Takatsuki K, Yamaguchi K, Kawano F, et al. Clinical aspects of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL). Princess Takamatsu Symp. 1984; 15:51–57. PMID: 6152759.

9. Wang C, Yao Z, Liao J, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic and ultrastructrual analyses of ATLL patients with cutaneous involvement. Chin Med J (Engl). 1999; 112:461–465. PMID: 11593520.

10. Tsukasaki K. Adult T cell leukemia-lymphoma (ATL). Nihon Rinsho. 2014; 72:531–537. PMID: 24724415.

11. Mori N. Cell signaling modifiers for molecular targeted therapy in ATLL. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2009; 14:1479–1489. PMID: 19273141.

12. Hatta Y, Koeffler HP. Role of tumor suppressor genes in the development of adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL). Leukemia. 2002; 16:1069–1085. PMID: 12040438.

13. Nicot C. HTLV-I Tax-mediated inactivation of cell cycle checkpoints and DNA repair pathways contribute to cellular transformation: “A Random Mutagenesis Model”. J Cancer Sci. 2015; 2.

14. Enose-Akahata Y, Abrams A, Massoud R, et al. Humoral immune response to HTLV-1 basic leucine zipper factor (HBZ) in HTLV-1-infected individuals. Retrovirology. 2013; 10:19. PMID: 23405908.

15. Magri MC, Costa EA, Caterino-de-Araujo A. LTR point mutations in the Tax-responsive elements of HTLV-1 isolates from HIV/HTLV-1-coinfected patients. Virol J. 2012; 9:184. PMID: 22947305.

16. Ishikawa C, Nakachi S, Senba M, Sugai M, Mori N. Activation of AID by human T-cell leukemia virus Tax oncoprotein and the possible role of its constitutive expression in ATL genesis. Carcinogenesis. 2011; 32:110–119. PMID: 20974684.

17. Shiohama Y, Naito T, Matsuzaki T, et al. Absolute quantification of HTLV-1 basic leucine zipper factor (HBZ) protein and its plasma antibody in HTLV-1 infected individuals with different clinical status. Retrovirology. 2016; 13:29. PMID: 27117327.

18. Shimoyama M. Diagnostic criteria and classification of clinical subtypes of adult T-cell leukaemia-lymphoma. A report from the Lymphoma Study Group (1984-87). Br J Haematol. 1991; 79:428–437. PMID: 1751370.

19. Dearden CE, Johnson R, Pettengell R, et al. Guidelines for the management of mature T-cell and NK-cell neoplasms (excluding cutaneous T-cell lymphoma). Br J Haematol. 2011; 153:451–485. PMID: 21480860.

20. Yared JA, Kimball AS. Optimizing management of patients with adult T cell leukemia-lymphoma. Cancers (Basel). 2015; 7:2318–2329. PMID: 26610571.

21. Kozako T, Arima N, Toji S, et al. Reduced frequency, diversity, and function of human T cell leukemia virus type 1-specific CD8+ T cell in adult T cell leukemia patients. J Immunol. 2006; 177:5718–5726. PMID: 17015761.

22. Clerc I, Hivin P, Rubbo PA, Lemasson I, Barbeau B, Mesnard JM. Propensity for HBZ-SP1 isoform of HTLV-I to inhibit c-Jun activity correlates with sequestration of c-Jun into nuclear bodies rather than inhibition of its DNA-binding activity. Virology. 2009; 391:195–202. PMID: 19595408.

23. Satou Y, Yasunaga J, Yoshida M, Matsuoka M. HTLV-I basic leucine zipper factor gene mRNA supports proliferation of adult T cell leukemia cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006; 103:720–725. PMID: 16407133.

24. Tamura K, Nagamine N, Araki Y, et al. Clinical analysis of 33 patients with adult T-cell leukemia (ATL)-diagnostic criteria and significance of high- and low-risk ATL. Int J Cancer. 1986; 37:335–341. PMID: 3005175.

25. Lee SY, Cheng V, Rodger D, Rao N. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of ocular syphilis: a new face in the era of HIV co-infection. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2015; 5:56. PMID: 26297110.

26. Massey AC, Weinstein DL, Petri WA, Williams ME, Hess CE. ATLL complicated by strongyloidiasis and isosporiasis: case report. Va Med Q. 1990; 117:311–316. PMID: 2375179.

27. Senba M, Kawai K. Metastatic calcification due to hypercalcemia in adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma (ATLL). Zentralbl Pathol. 1991; 137:341–345. PMID: 1768685.

28. Shu ST, Martin CK, Thudi NK, Dirksen WP, Rosol TJ. Osteolytic bone resorption in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010; 51:702–714. PMID: 20214446.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download