HLH occurs as either a primary (familial) [

4] or a secondary (sporadic) disorder [

56]. Both conditions manifest pathological immune activation and may be difficult to differentiate from each other. Primary HLH is an autosomal recessive disease with an incidence of 1 per 50,000 live-born children [

5]. Younger patients often have a clear familial inheritance or genetic mutation. The median survival is <2 months if untreated. Immunological triggers such as vaccinations and viral infections may trigger bouts of disease in these patients. However, in many circumstances, no clear-cut immunological trigger is identifiable. Secondary HLH [

7] includes adults and older children who lack a family history or known genetic cause of HLH. The diagnostic criteria for HLH were mainly derived from studies in the pediatric population, but characteristics of adult HLH are now recognized [

8]. Secondary HLH often occurs as a result of pathological immune activation in response to a trigger. The frequently noted triggers include malignancy [

9] (especially hematological malignancies, including acute leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, and myelofibrosis), infections (especially viruses such as EBV and CMV), and rheumatological disorders [

2810]. Immune-activated and immune-mediated pathologies likely play a central role in the evolution of HLH. These represent acute clinical signs and symptoms of immune activation, including hepatomegaly, jaundice, adenopathy, rash, seizures, and focal neurologicneurological deficits, as well as abnormaly high serum level of cytokines such as interferon gamma (IFNγ), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-10, and macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) [

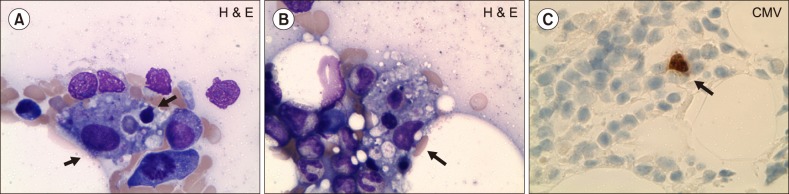

1112]. Biopsies of lymphoid tissues or histological examination of liver tissue from HLH patients reveals highly activated macrophages and lymphocytes, supporting striking activation of the immune system [

10]. Therefore, the goal of initial therapy is to suppress the hyperactive immune system for preventing immune-mediated irreversible organ damage [

13]. Induction therapy is often followed by allogeneic stem cell transplantation if a suitable donor is available. If no suitable donor is identified, patients should be followed up closely for signs of relapse. The HLH-94 protocol proposed in 1997 [

14] included an 8-week regimen of etoposide, dexamethasone, and intrathecal methotrexate. The clinical profile of our patient was complex, and HLH in an elderly patient without any preexisting factor supporting an immunocompromised state is unusual. The clinical features that raised the suspicion of HLH were fever, cytopenia, organomegaly, coagulopathy, liver function abnormalities, elevated ferritin level, and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytic in the BM. Disseminated CMV associated with HLH is uncommon in adults, and anecdotal pediatric cases were reported [

15]. Early recognition and treatment of HLH are essential, and rare pathogens such as CMV should be considered as a cause of HLH.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download