Abstract

Background

Although intravenous acyclovir therapy is recommended for varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection in immunocompromised children, the clinical characteristics and outcomes of VZV infection in the acyclovir era have rarely been reported.

Methods

The medical records of children diagnosed with varicella or herpes zoster virus, who had underlying hematologic malignancies, were retrospectively reviewed, and the clinical characteristics and outcomes of VZV infection were evaluated.

Results

Seventy-six episodes of VZV infection (herpes zoster in 57 and varicella in 19) were identified in 73 children. The median age of children with VZV infection was 11 years (range, 1-17), and 35 (46.1%) episodes occurred in boys. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia was the most common underlying malignancy (57.9%), and 90.8% of the episodes occurred during complete remission of the underlying malignancy. Acyclovir was administered for a median of 10 days (range, 4-97). Severe VZV infection occurred in 16 (21.1%) episodes. Although the finding was not statistically significant, a previous history of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) appeared to be associated with the development of more severe episodes of herpes zoster (P=0.075).

Conclusion

Clinical characteristics of VZV infection in immunocompromised children were not significantly different from those without it, and clinical outcomes improved after the introduction of acyclovir therapy. However, risk factors for severe VZV infection require further investigation in a larger population and a prospective setting.

Primary infection with varicella zoster virus (VZV) in children causes varicella, after which VZV maintains latency in the dorsal root ganglia [1]. The latent VZV may be reactivated and cause herpes zoster when host cellular immunity is weakened [1], and 27.9% of children diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) experience herpes zoster during their primary chemotherapy course [2]. Most immunocompetent patients spontaneously recover from varicella and herpes zoster with only symptomatic therapy and rarely experience complications [3], whereas morbidity and mortality due to varicella and herpes zoster are increased in immunocompromised patients [4567]. Before the introduction of antiviral therapy for VZV infection, 31.7% of children diagnosed with varicella during chemotherapy for acute leukemia experienced visceral dissemination of VZV, and 6.7% of these children died [4]. Without antiviral therapy, complications and deaths due to herpes zoster in children with cancers occurred in 11.9% and 3.0% of patients, respectively [5]. Although a decrease in severe infections and deaths due to VZV infection has been noted in immunocompromised children treated with antiviral therapy, reports on the clinical characteristics and outcomes of VZV infection in immunocompromised children after the introduction of antiviral therapy are rare [2].

This retrospective study was performed to investigate changes in clinical characteristics and outcomes of VZV infection in immunocompromised children receiving antiviral therapy for VZV infection.

A retrospective review was performed on the medical records of children aged 18 years or younger who were diagnosed with VZV infection (varicella and herpes zoster) between April 2009 and March 2015 at Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, Seoul, Korea. Among this group, children with underlying hematologic malignancies (acute/chronic leukemia and lymphoma) were included in the present study. Demographic characteristics including gender and age and clinical characteristics including the type and status of underlying hematologic malignancy, chemotherapy administered before the development of VZV infection, symptoms accompanying VZV infection, severe infections involving organs or multiple dermatomes, and the duration of antiviral therapy were investigated. Laboratory test results including white blood cell (WBC) count; absolute neutrophil, lymphocyte, and monocyte counts (not shown); erythrocyte sedimentation rate; and C-reactive protein level at the time of diagnosis of VZV infection were also investigated. In addition, the presence of serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM against VZV, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test results for VZV in the serum, and Tzanck test results were investigated. The enrolled children were divided into two groups based on the development of complications associated with each of the VZV infections: varicella and herpes zoster; complicated infections were defined as proven or probable organ involvement without evidence of diseases other than VZV, or cutaneous dissemination of herpes zoster. The investigated demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics were compared between the two groups for each presentation of VZV infection. The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, and the requirement for informed consent was waived (Approval No.: KC15RISI0233).

VZV infection included both varicella and herpes zoster. The diagnosis of varicella and herpes zoster were performed by two independent pediatricians based on clinical manifestations. Herpes zoster was diagnosed when pruritic papulovesicular skin lesions developed with a dermatomal distribution, and varicella was diagnosed when the characteristic skin lesions were scattered and without a dermatomal distribution [8]. Cutaneous dissemination of herpes zoster was diagnosed when two or more separated dermatomes were involved. Visceral organ involvement was diagnosed based not on the histologic findings of the biopsied tissue but on the clinical and laboratory findings. Pneumonia was diagnosed in cases when abnormal breathing sounds were heard on auscultation and chest radiography revealed abnormal infiltrations in a child with respiratory symptoms. Hepatitis was diagnosed when the serum aspartate transaminase or alanine transaminase levels increased two-fold or more during VZV infection compared with the levels measured before VZV infection in a child with symptoms consistent with acute hepatitis, such as abdominal pain, hepatomegaly, nausea, vomiting, and jaundice. Cases in which other causes of hepatitis or pneumonia were ruled out via respiratory viral PCR or serologic studies were considered complicated VZV infections. Meningitis was diagnosed when a cerebrospinal fluid sample collected from a child with neurological symptoms such as headache, seizures, and paralysis showed pleocytosis (WBC count >5 cells/µL), and encephalitis was diagnosed when seizures or mental dysfunction was present in a child with meningitis. Severe infections due to VZV were associated with visceral organ involvement, cutaneous dissemination of herpes zoster, and intensive care unit (ICU) care and/or deaths.

The enrolled children were divided into two groups depending on whether complications due to VZV infection were present, and demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics were compared between the two groups. Categorical factors were compared between the two groups using the χ2 test, and continuous factors were compared using the Mann-Whitney test. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed P-value<0.05.

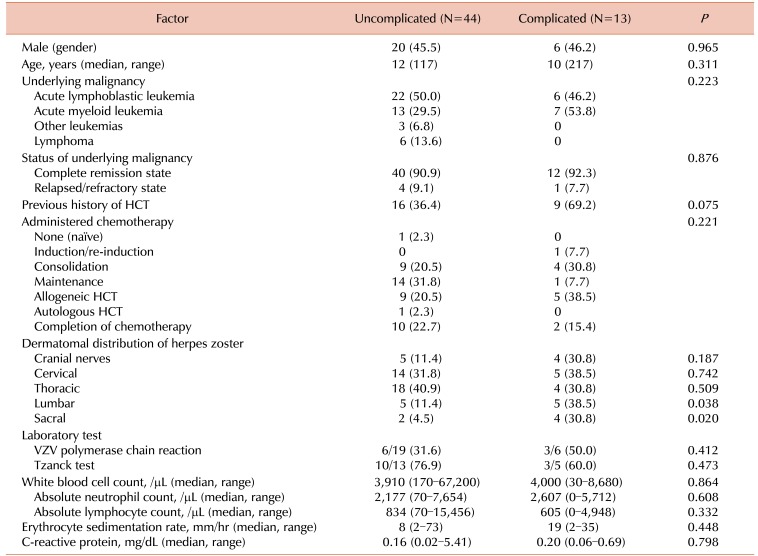

During the study period, 76 episodes of VZV infection were diagnosed in 73 children with hematologic malignancies (Table 1). There were 57 (75.0%) episodes of herpes zoster and 19 (25.0%) episodes of varicella, and 3 children experienced 2 episodes of herpes zoster. The median age of the enrolled children was 11 years (range, 1–17), and 35 (46.1%) episodes occurred in boys. The ALL was the most common underlying malignancy (44 episodes, 57.9%), and 56.8% of the children with ALL were categorized into a very high-risk group (data not shown). Sixty-nine (90.8%) episodes of VZV infection occurred during a state of complete remission of the underlying malignancy. A previous history of receiving allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) was identified in 32 (42.1%) episodes, and 1 (1.3%) child had received an autologous HCT; in particular, there were 15 (15/57, 26.3%) episodes of HCT in cases of herpes zoster and 5 (5/19, 26.3%) episodes, in cases of varicella. VZV infection occurred most frequently during maintenance chemotherapy (22 episodes, 29.0%) and after allogeneic HCT (19 episodes, 25.0%). Fifteen (19.7%) episodes occurred after completion of a course of chemotherapy. Fever was the most common symptom accompanying VZV infection (data not shown; 34 episodes, 44.7%), and gastrointestinal symptoms were the most frequent focal symptoms (9 episodes, 11.8%). Thoracic (22 episodes, 38.6%) and cervical (19 episodes, 33.3%) dermatomes were most commonly involved during the 57 episodes of herpes zoster. The presence of serum IgG and IgM against VZV was examined during 37 and 36 episodes, respectively. Tests for IgG were positive in 22 episodes (59.5%), but tests for IgM were not positive in any of the episodes. VZV PCR testing using serum samples were performed during 35 episodes, and 18 (51.4%) of the tests were positive. Tzanck tests from the skin lesions were positive in 17 (68.0%) of the 25 tested episodes.

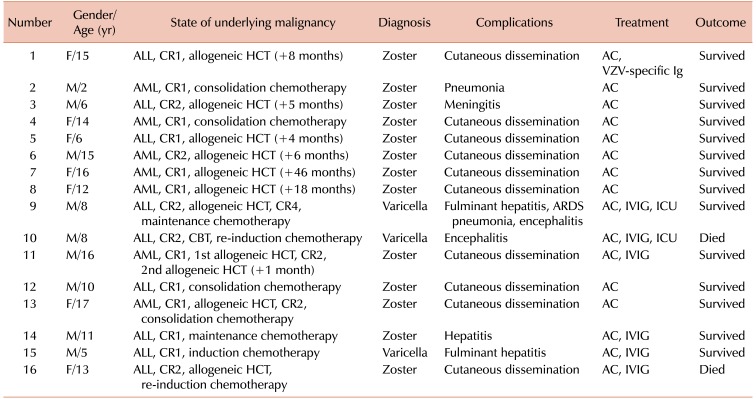

In all 76 episodes of VZV infection, the children were immediately hospitalized and received intravenous acyclovir therapy (10 mg/kg or 500 g/m2 of body surface area, 3 times daily) for a median of 9 days (range, 2–97). In 40 (52.6%) episodes, oral acyclovir therapy (20 mg/kg 4 times daily) for a median of 2 days (range, 0–9) was additionally administered following discharge from the hospital. The entire duration of acyclovir therapy was a median of 10 days (range, 4–97). One patient received acyclovir therapy for a shorter duration than recommended because of renal impairment. Complicated VZV infection occurred in 16 (21.1%) episodes, including 13 (81.2%) in herpes zoster and 3 (18.8%) in varicella (Table 2A, B). Two (2.6%) children received ICU care, 1 under mechanical ventilation and the other for encephalitis. Cutaneous dissemination occurred in 10 (76.9%) of the 13 complicated episodes of herpes zoster. Among the 10 episodes, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and VZV-specific immunoglobulin were administered for 2 (20.0%) and 1 (10.0%) episodes, respectively. One of the children with cutaneous dissemination of herpes zoster died of leukemia progression. She experienced herpes zoster after reinduction chemotherapy for relapsed ALL within 1 year after allogeneic HCT. Although she received intravenous acyclovir and IVIG therapy, her skin lesions persisted for more than 3 months, and she eventually died of leukemia progression. Another child with herpes zoster experienced hepatitis, and he recovered with acyclovir and IVIG therapy. The remaining 2 children with complicated VZV infections presenting with herpes zoster experienced meningitis and pneumonia, respectively, and both recovered with only acyclovir therapy without IVIG.

Three children experienced complicated varicella infections. One of them experienced varicella with encephalitis during reinduction chemotherapy for relapsed ALL after cord blood transplantation. Although he received acyclovir and IVIG therapy, his mental function did not recover and eventually died of bacterial sepsis in a refractory ALL state. Another child experienced varicella with fulminant hepatitis, pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and encephalitis during maintenance chemotherapy for a third remission of ALL after allogeneic HCT, and he recovered with acyclovir and IVIG therapy. The third child experienced varicella with fulminant hepatitis after induction chemotherapy for ALL, and he recovered with acyclovir and IVIG therapy.

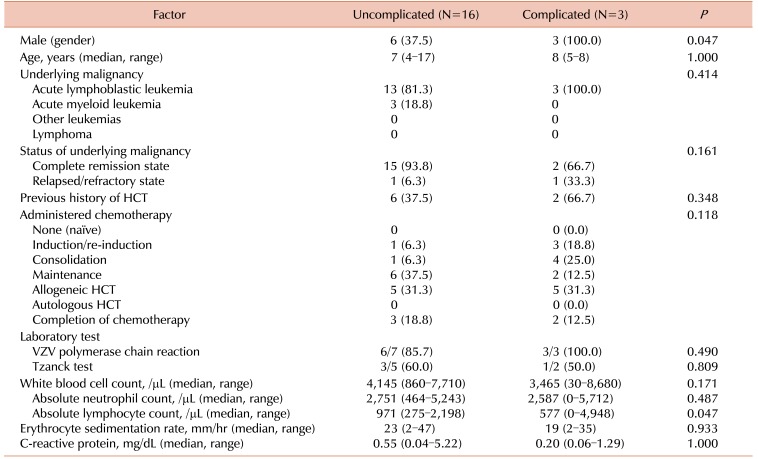

Between children with and without complicated infections due to VZV infection, there were no significant differences regarding age, type of VZV infection, type of underlying malignancy, and administered therapy before the development of VZV infection (Table 2A, B). Among children with herpes zoster, lumbar and sacral dermatomes were more frequently involved in children with complications than in those without complications (P=0.038 and P=0.020, respectively). The duration of administration of acyclovir was longer in children with complications compared to the duration in those without complications (P=0.001), and the durations were similar in each of the presenting infections, varicella and herpes zoster (P=0.002, P=0.036, respectively). IVIG was more frequently administered to children with complications than to those without complications (P<0.001). Laboratory test results did not significantly differ between the two groups. Clinical details of children with complicated VCZ infection are summarized in Table 3.

In the present study, clinical characteristics and outcomes of VZV infection in children with underlying hematologic malignancies who received acyclovir therapy were evaluated. Complications due to VZV infection occurred in 21.1% of the enrolled children, and 2 (2.6%) children died; however, there were no deaths closely associated with VZV infection.

Clinical manifestations of VZV infection in children with hematologic malignancies in the present study were similar to those reported previously. Herpes zoster occurred more frequently in children with ALL compared to those with acute myeloid leukemia or solid tumors [56], and more than half of the enrolled children in the present study had underlying ALL. In children with ALL, the rate of occurrence of herpes zoster differed according to the children's risk groups [2], and most of the children with underlying ALL in the present study were included in a very high-risk group (data not shown). This result may be attributable to differences in the intensity of administered chemotherapy according to the risk group [2]. In addition, older children were included in the higher-risk groups, and VZV infection tends to occur more frequently in older children compared with younger children. In previous studies, VZV infection was found to be more severe among HCT recipients than in other immunocompromised patients [910], but no statistically significant difference was observed. Abdominal pain preceding the development of skin lesions has been associated with an increased severity of VZV infection [711], and gastrointestinal symptoms occurred more frequently in children with complications than in those without complications in the present study, although the difference was not statistically significant. Some previous studies reported that low absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) is associated with development of visceral dissemination and increased mortality in children with cancer and varicella [46]; similarly, in the present study, a low ALC was related to the development of complicated varicella (P=0.047).

Before the introduction of acyclovir therapy for VZV infection, a 6.7% of mortality rate was reported in children with ALL with varicella, and a 3.0% mortality rate was reported in children with cancer and herpes zoster [45]. However, there were no reported deaths due to VZV infection in immunocompromised children receiving acyclovir therapy [26]. In the present study, 2 (2.6%) children died; their cause of death was not VZV infection but progression of malignancies.

Currently, intravenous acyclovir has been recommended for the treatment of VZV infection in children with underlying acute leukemia who are receiving HCT [1]; therefore, all children enrolled in the present study received intravenous acyclovir therapy and were hospitalized immediately after the clinical diagnosis of VZV infection. However, universal hospitalization for intravenous acyclovir therapy caused increase of hospital costs and complications related to injection as well as concern of the development of hospihospital-acquired infection. Considering the favorable therapeutic effect of acyclovir on VZV infection in immunocompromised children, oral acyclovir therapy could be an option in cases of uncomplicated VZV infections. Sørensen et al. [2] reported that there were no cases of visceral involvement and no deaths in children with ALL and herpes zoster receiving oral acyclovir therapy for 5 to 10 days. Because of its low bioavailability in oral acyclovir, studies have been conducted on the therapeutic effect of valacyclovir and famciclovir, which have improved oral bioavailability [1213]. The use of oral famciclovir and valacyclovir has been approved for varicella and herpes zoster in immunocompetent adults, and the therapeutic effect of these agents has been proved in immunocompromised adults with VZV infection [1213]. Although there has been no randomized controlled study that has examined the therapeutic effect of valacyclovir and famciclovir in immunocompromised children with VZV infection, a therapeutic effect of famciclovir on VZV infection in immunocompetent children has been reported [14]. In immunocompromised children, it was reported that a therapeutic blood drug level could be maintained with oral valacyclovir therapy [15]. Therefore, further studies evaluating the clinical therapeutic effect of oral famciclovir and valacyclovir in immunocompromised children with varicella and herpes zoster should be performed. Until then, oral acyclovir therapy may be applicable in immunocompromised children without risk factors for complicated VZV infection. Although our study failed to show significant association between previous history of HCT and development of complicated VZV infection, some studies reported that a previous history of HCT was related to severe VZV infections [910], and severe VZV infection increased in patients with ALL who received steroid therapy within 3 weeks [16]. Accordingly, oral acyclovir therapy can be tried in cases of immunocompromised children who have not undergone HCT and have not recently received steroid therapy.

The present study has several limitations. Because this study was conducted retrospectively and restricted to a small number of patients and the experience of a single institute, the exact incidence of VZV infection was not determined according to the type and risk group of underlying hematologic malignancies and the type of administered chemotherapy. A previous history of VZV infection and vaccination against varicella could not be determined by a review of medical records. Patient immune status against VZV could not be determined because we did not perform serological tests for VZV at the time of diagnosis of hematologic malignancy.

Seropositivity for VZV increased the occurrence rate of herpes zoster in children with ALL [29], and the occurrence rate of herpes zoster was lower in children who were vaccinated for varicella than in those who had varicella [17]. If we consider that varicella vaccination has been universally administered in Korea since 2005 as part of the National Immunization Program, future studies should be performed to evaluate the effect of previous vaccination on the incidence of VZV infection in immunocompromised children. However, some children who were seropositive for VZV at the time of diagnosis of leukemia became seronegative after chemotherapy [18], and 59.5% of the children tested for IgG against VZV in the present study were seropositive for VZV despite the development of VZV infection. Considering that the cellular immunity has an important role in controlling VZV infection [1], an estimation of cellular immune responses to VZV rather than humoral immunity may be useful for predicting the development of VZV infection and its complications. In the present study, cases of clinically diagnosed VZV infection were investigated. It is known that VZV PCR is a very sensitive tool for detecting VZV infection, VZV PCR tests with serum were performed in only 35 (46.1%) episodes of our study and the results were positive in 51.5% of tests.The VZV PCR using blood samples is helpful to verify the potential risk for viral dissemination, and VZV PCR using vesicular swabs is a more accurate tool for the diagnosis of VZV infection [19]. Therefore, in future studies, the relationship between VZV PCR in the serum and complicated VZV infection should be investigated.

In conclusion, clinical characteristics of VZV infection in immunocompromised children were not significantly changed and clinical outcomes were improved after the introduction of acyclovir therapy. However, in the future, the risk factors for complicated VZV infections should be further investigated in a larger patient population and from a prospective viewpoint. In addition, oral antiviral therapy may be attempted for immunocompromised children with no risk factors for complicated VZV infection.

References

1. Gershon AA. Varicella-zoster virus. In : Cherry DS, Harrison GJ, Kaplan SL, Steinbach WJ, Hotez PJ, editors. Fiegin and Cherry's textbook of pediatric infectious diseases. 17th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders;2014. p. 2021–2033.

2. Sørensen GV, Rosthøj S, Würtz M, Danielsen TK, Schrøder H. The epidemiology of herpes zoster in 226 children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011; 57:993–997. PMID: 21254379.

3. Bovill B, Bannister B. Review of 26 years' hospital admissions for chickenpox in North London. J Infect. 1998; 36(Suppl 1):17–23.

4. Feldman S, Hughes WT, Daniel CB. Varicella in children with cancer: Seventy-seven cases. Pediatrics. 1975; 56:388–397. PMID: 1088828.

5. Feldman S, Hughes WT, Kim HY. Herpes zoster in children with cancer. Am J Dis Child. 1973; 126:178–184. PMID: 4353308.

6. Feldman S, Lott L. Varicella in children with cancer: impact of antiviral therapy and prophylaxis. Pediatrics. 1987; 80:465–472. PMID: 2821476.

7. Morgan ER, Smalley LA. Varicella in immunocompromised children. Incidence of abdominal pain and organ involvement. Am J Dis Child. 1983; 137:883–885. PMID: 6613954.

9. Novelli VM, Brunell PA, Geiser CF, Narkewicz S, Frierson L. Herpes zoster in children with acute lymphocytic leukemia. Am J Dis Child. 1988; 142:71–72. PMID: 3277389.

10. Ljungman P, Lönnqvist B, Gahrton G, Ringdén O, Sundqvist VA, Wahren B. Clinical and subclinical reactivations of varicella-zoster virus in immunocompromised patients. J Infect Dis. 1986; 153:840–847. PMID: 3009635.

11. Rowland P, Wald ER, Mirro JR Jr, et al. Progressive varicella presenting with pain and minimal skin involvement in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1995; 13:1697–1703. PMID: 7602360.

12. Mubareka S, Leung V, Aoki FY, Vinh DC. Famciclovir: a focus on efficacy and safety. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2010; 9:643–658. PMID: 20429777.

13. Vigil KJ, Chemaly RF. Valacyclovir: approved and off-label uses for the treatment of herpes virus infections in immunocompetent and immunocompromised adults. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010; 11:1901–1913. PMID: 20536295.

14. Sáez-Llorens X, Yogev R, Arguedas A, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of famciclovir in children with herpes simplex or varicella-zoster virus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009; 53:1912–1920. PMID: 19273678.

15. Bomgaars L, Thompson P, Berg S, Serabe B, Aleksic A, Blaney S. Valacyclovir and acyclovir pharmacokinetics in immunocompromised children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008; 51:504–508. PMID: 18561175.

16. Hill G, Chauvenet AR, Lovato J, McLean TW. Recent steroid therapy increases severity of varicella infections in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatrics. 2005; 116:e525–e529. PMID: 16199681.

17. Brunell PA, Taylor-Wiedeman J, Geiser CF, Frierson L, Lydick E. Risk of herpes zoster in children with leukemia: varicella vaccine compared with history of chickenpox. Pediatrics. 1986; 77:53–56. PMID: 3455669.

18. Patel SR, Bate J, Maple PA, Brown K, Breuer J, Heath PT. Varicella zoster immune status in children treated for acute leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014; 61:2077–2079. PMID: 24789692.

19. Sauerbrei A. Diagnosis, antiviral therapy, and prophylaxis of varicella-zoster virus infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016; 35:723–734. PMID: 26873382.

Table 1

Characteristics of 76 episodes of varicella zoster virus infection in children with hematological malignancies.

Table 2A

Comparison between children with and without severe infections presenting with herpes zoster.

Table 3

Characteristics of children with varicella zoster virus infection with accompanying complications.

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CR, complete remission; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; AC, acyclovir; VZV, varicella zoster virus; Ig, immunoglobulin; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; ICU, intensive care unit; CBT, cord blood transplantation.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download