Abstract

Background

While venous thromboembolism (VTE) is uncommon, its incidence is increasing in children. We aimed to evaluate the incidence, risk factors, treatment, and outcome of pediatric VTE cases at a single tertiary hospital in Korea.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed the records of consecutive pediatric VTE patients admitted to the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital between April 2003 and March 2016.

Results

Among 70,462 hospitalizations, 25 pediatric VTE cases were identified (3.27 cases per 10,000 admissions). Fifteen patients (60%) were male, 8 were neonates (32%), and the median age at diagnosis was 10.9 years (range, 0 days‒17 yr). Doppler ultrasonography was the most frequently used imaging modality. Thrombosis occurred in the intracerebral (20%), upper venous (64%), lower venous (12%), and combined upper and lower venous systems (4%). Twenty patients (80%) had underlying clinical conditions including venous catheterization (24%), malignancy (20%), and systemic diseases (12%). Protein C, protein S, and antithrombin deficiencies occurred in 2 of 13, 4 of 13, and 1 of 14 patients tested, respectively. Six patients were treated with heparin followed by warfarin, while 4 were treated with heparin or warfarin. Thrombectomy and inferior vena cava filter and/or thrombolysis were performed in 5 patients. Two patients died of pulmonary embolism, and 2 developed a post-thrombotic syndrome.

Go to :

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), a disease that includes both deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, is a rare condition in children. Nevertheless, its incidence has reportedly increased recently [12]. The ability to correctly detect and diagnose thrombotic events in pediatric patients has been improving as a result of continuous advances in the treatment and supportive care of critically ill children, as well as the increased knowledge and awareness of thrombotic complications and genetic risk factors for thrombosis [234].

An accurate estimate of pediatric VTE incidence is not available as only a few prospective studies have been reported [356]. These studies have estimated a yearly VTE incidence of 0.07–0.14 cases per 10,000 children, or 5.3 cases per 10,000 pediatric hospital admissions, and 24 cases per 10,000 admissions to the neonatal intensive care units [57]. In tertiary care hospitals in the United States, the reported VTE rates are higher, and a 70% increase in its incidence has been observed from 2001 to 2007, i.e., from 34 to 58 cases per 10,000 children [3].

Most children with VTE have multiple risk factors, such as venous catheters, surgery, trauma, malignancy, and chronic inflammatory conditions [458910]. Infants aged under 1 year constitute the largest proportion of pediatric VTE patients, with adolescents constituting the second largest [456].

Most reports on the incidence of VTE are primarily from Western populations; however, there are significant differences between the Asian and Western countries with respect to the genetic background and demographic features. Therefore, considering the clinical significance of pediatric VTE, a population-specific epidemiologic study is imperative in order to assess the incidence, risk factors, treatment, and outcome of VTE in Korean children. With this aim, we conducted a retrospective review of the records of all VTE pediatric patients admitted to a single tertiary hospital in Korea over a period of 13 years.

Go to :

We retrospectively analyzed consecutive patients aged 0–18 years, who were diagnosed with VTE between April 2003 and March 2016 at the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (SNUBH). Hospital admission rates were obtained from the Health Information System Department of the SNUBH. Based on the hospital electronic database, patients were classified as potential VTE cases if they were assigned the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) codes I269, I749, I676, I802, I81, or I829, or if they were prescribed anticoagulant medication. Cases with multiple admissions for VTE were counted as a single incidence.

VTE was defined as a thrombotic occlusion of any vein within the deep venous system, pulmonary vasculature, right heart, or the cerebral venous sinuses. The thrombosis location was classified as central nervous system (intracranial veins and sinuses), the upper venous system (superior vena cava, right heart, pulmonary vessels, neck, and upper limb veins), or the lower venous system (inferior vena cava and all subsequent venous branches). VTE was confirmed by various imaging techniques including a Doppler ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) scanning, and magnetic resonance image (MRI) scanning. Thrombophilia test was performed using commercially available clinical assays.

The data for patient demographics, clinical presentation, the location of thrombosis, associated risk factors, family history, laboratory evaluations, treatment, and complications of the thrombotic event such as mortality and occurrence of post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS) were obtained through a review of the electronic medical records. Based on the age at the time of thrombosis diagnosis, patients were classified as neonates (aged<1 mo), infants (aged 1–12 mo), children (aged 1–12 yr), and adolescents (12–18 yr). All data were descriptively presented and analyzed based on the above-mentioned age groups.

This study was approved by the SNUBH Institutional Review Board (IRB approval No. B-1604/343-107). Informed consent was waived by the board.

Go to :

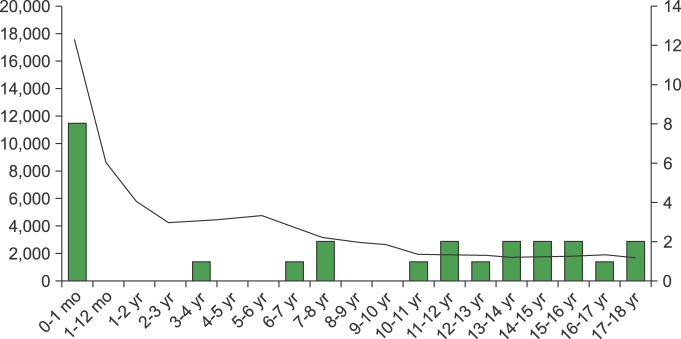

Of the 70,462 hospitalizations during the 13-year study period, we identified 220 patients as potential VTE cases. Following the criteria described in the methods section, a total of 25 patients were subsequently identified with a verified diagnosis of VTE. The total incidence of VTE was 3.27 cases per 10,000 admissions (0.0327%). The baseline and clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. Fifteen VTE patients were male (60%), and the median age at diagnosis was 10.9 years (range, 0 days–17 yr). Of the patients with VTE, 8 (32%) were neonates, 7 (28%) were children, and 10 (40%) were adolescents. Fig. 1 shows the age wise distribution of the pediatric patients with VTE and the total number of hospitalized patients stratified by age group.

Doppler ultrasonography was the most frequently used diagnostic imaging study, followed by CT, and MRI (Table 2). Pulmonary embolism was diagnosed using chest CT, ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scan, and an echocardiography. Intracranial VTE, including cerebral venous sinus thrombosis and central retinal vein thrombosis, was diagnosed using MRI with magnetic resonance venography. The locations of thrombosis were as follows: intracerebral venous systems in 5 cases (cerebral venous sinus, 4; central retinal vein throm bosis, 1), upper venous systems in 16 cases (pulmonary vessel, 5; internal jugular vein, 2; portal vein, 7; portal and renal veins, 1; superior mesenteric vein, 1), lower venous systems in 3 cases (inferior vena cava and iliac vein, 1; iliac and femoral veins, 1; femoral vein, 1), and combined upper and lower venous systems in 1 case (pulmonary vessel, inferior vena cava, and popliteal vein, 1).

Of the 25 VTE patients, 20 exhibited at least one underlying clinical condition (80%) (Table 3). Among the known risk factors for VTE, we identified the following: venous catheterization in 6 cases (umbilical venous catheter, 4; femoral catheter, 2); malignancy in 5 cases (acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with L-asparaginase, 3; brain tumor with a Hickman catheter, 1; and lymphoma with an internal jugular vein catheter, 1); systemic disease in 3 cases (nephrotic syndrome, 1; systemic lupus erythematosus, 1; and systemic infection, 1); prematurity in 1 case; a mother with gestational diabetes mellitus in 2 cases; trauma in 1 case; and venous anomalies in 2 cases.

A test for thrombophilia was performed in some patients (Table 4). Two patients exhibited an underlying protein C deficiency, 4 exhibited protein S deficiency including 1 case of transient protein S deficiency, and 1 patient exhibited an antithrombin deficiency. A lupus anticoagulant antibody test was positive in 3 of the 13 tested patients; anti-cardiolipin IgG and IgM antibodies were positive in 4 out of the 14 tested patients; while the anti-β2 glycoprotein I IgG antibody was undetectable in all 11 tested patients.

A total of 10 patients received an initial anticoagulant therapy for the acute phase of thrombosis. Six patients received unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), followed by warfarin, while 4 patients received either LMWH or warfarin. Seven patients with residual thrombus or VTE risk factors such as congenital thrombophilia, or venous anomaly received long-term treatment with warfarin (range, 2 yr–9 yr, 8 mo). In 1 patient, the warfarin treatment was discontinued after 3 months due to bleeding complications including epistaxis and menorrhagia. Four patients underwent surgical treatments including thrombectomy and IVC filter, or thrombolysis followed by anticoagulation. One patient died due to a pulmonary embolism following thrombolysis, before the anticoagulation treatment could be started. Four patients underwent a catheter removal and follow-up observations, while 3 patients were treated without an anticoagulant. Treatment was unknown for 3 patients who were transferred to other hospitals or were lost to follow-up (Table 5).

Of the 25 VTE patients, 12 exhibited a complete resolution of VTE, 7 had persistent VTE, and 2 patients died of pulmonary emboli. We did not note a recurrence of VTE in patients following a complete resolution of the thrombus. One patient with a venous anomaly discontinued the warfarin treatment when the thrombus stabilized, and subsequently experienced an aggravation of the thrombus. PTS developed in 2 of the 5 patients (20%) with a lower venous system VTE, resulting in stasis ulcer and varicose vein after 2 years and 9 years of initial VTE diagnosis, respectively.

Go to :

The incidence of VTE is significantly lower in children compared with adults, suggesting the presence of protective mechanisms [11]. In children, the coagulation system develops with age, as evidenced by significant age-related differences in the concentration of most clotting factors, a concept known as 'developmental hemostasis' [11].

In a nationwide epidemiologic study in the Korean population, the annual incidence of VTE in 2008 was reported as 13.8 cases per 100,000 individuals [12], which is significantly lower than the annual incidence noted for the Caucasian population (143 cases per 100,000 individuals) [13]. Furthermore, the incidence of VTE in Korean youth was even lower, with a reported 0.09 cases per 10,000 individuals aged 0–19 years [12].

In our study, the incidence of VTE was 3.27 cases per 10,000 pediatric patients. This rate was higher than the previously reported VTE incidence in the general Korean pediatric population but was lower than the incidence reported from Western countries, where the incidence rate ranged from 8 to 60 cases per 10,000 hospital admissions [414,15]. Furthermore, the age-stratified VTE incidence exhibited a bimodal distribution, with a peak VTE incidence in the adolescents (9.47 cases per 10,000 adolescents admitted) rather than in the neonates (4.57 cases per 10,000 neonates admitted).

In comparison with the older children, neonates are at an increased risk of bleeding and thrombotic complications owing to the altered levels of procoagulants; anticoagulants; and fibrinolytic factors, with these risk factors being especially relevant in the presence of other hemostatic challenges such as an indwelling catheter [1116]. Asphyxia, maternal diabetes, polycythemia, sepsis, poor cardiac output, and dehydration are additional VTE risk factors for the neonates [16]. Furthermore in preterm infants, the levels of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors are lower than those in the infants born at term; preterm infants also have lower levels of coagulation inhibitors, including antithrombin and protein C [17]. The preterm infants are also particularly at risk in response to the perinatal risk factors and iatrogenic events [16]. In the present study, all 8 neonates had VTE associated clinical risk factors including venous catheter (N=4), prematurity (N=1), a mother with gestational diabetes mellitus (N=2), and venous anomaly (N=1).

In the United States, approximately 25% to 50% of the adult patients with first-time VTE have an idiopathic condition with no immediately obvious risk factors [18]. Unlike adults, however, approximately 80% of the VTE episodes in children and adolescents are reportedly associated with an underlying chronic condition [1920]. Pediatric VTE is a multifactorial disease, and the clinical factors appear to have a greater influence on the risk for VTE than an inherited thrombophilia, especially in catheter-related VTE [410]. In pediatric patients, the presence of a venous catheter is the most significant risk factor for VTE, accounting for approximately 90% of all neonatal, and 60% of all childhood VTE cases [510]. This is most likely a result of an increased risk of thrombosis owing to the damaged endothelial lining and disrupted blood flow from the central venous catheters. The most common medical conditions associated with thrombosis are cancer, congenital heart disease, and prematurity. In our study population, 20 of the 25 patients (80%) had underlying clinical conditions, with venous catheterization and malignancy being the most frequent.

Although a strong association between inherited prothrombotic disorders and VTE has been shown in adults, the impact of these disorders on the development of VTE in children remains controversial [221]. In the pediatric VTE patients from Western countries, the incidence of inherited prothrombotic disorders ranges from 10% to 59% [2223]. The relationship between VTE and certain inherited defects is well understood, such as the factor V Leiden mutation, the prothrombin gene mutation, and the protein C, protein S, and antithrombin deficiencies [2223]. Certain genetic mutations, particularly the factor V Leiden and factor II G20210A, are highly prevalent in the Caucasian population but are virtually absent in the Asian population [242526].

Thrombophilia testing is rarely considered in the acute management of thrombotic events in pediatric patients [2]. However, the identification of inherited thrombophilia may influence the treatment duration, particularly in patients with combined defects, and may aid in optimal patient counseling for risk factors associated with a VTE-recurrence [22]. It is difficult to apply the results of coagulation studies conducted in adults to the evaluation of pediatric patients as there are significant differences in the stages of hemostatic system development, as well as in the normal ranges of relevant biochemical markers and the laboratory assays employed to assess the anticoagulant levels [11]. Therefore, it is essential to refer to the age-specific normal ranges when interpreting the results of pediatric coagulation studies. In our study, thrombophilia tests were not performed uniformly; only 13 patients were tested for protein C and protein S deficiencies, with positive results observed in 2 and 4 patients, respectively. Of these, 1 patient with protein C deficiency had a positive family history. Similarly, only 14 patients were tested for antithrombin deficiency, with a positive test result in 1 patient.

An ultrasound with a Doppler flow is the most commonly employed imaging study for the diagnosis of upper, or more frequently lower, extremity VTE [12]. Other noninvasive diagnostic imaging options including CT and MR venography are particularly helpful in evaluating proximal thrombosis [12]. For the diagnosis of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, the most sensitive imaging modality is a brain MRI with venography or a diffusion-weighted imaging [12]. In this study, Doppler ultrasonography was the most frequently used diagnostic imaging modality, followed by CT, and MRI. Pulmonary emboli were diagnosed using chest CT, V/Q scan, and echocardiography. Intracranial VTE, including cerebral venous sinus thrombosis and central retinal vein thrombosis, were diagnosed using an MRI with venography.

Treatment recommendations for pediatric VTE cases are based on the data from studies conducted in the adult population [27]. However, there is a need for separate recommendations for pediatric patients as there are age-based differences in the disease etiology and the available treatment options [28]. The patients in our study population were managed using anticoagulation and surgical treatments, and unfractionated heparin or LMWH with vitamin K antagonist were the most frequently used treatments. Thrombectomy or thrombolysis was indicated only in life- or limb-threatening cases. Catheter removal was performed in four patients without anticoagulation.

PTS, characterized by venous insufficiency, is a chronic complication of VTE; the symptoms of PTS range from mild edema to chronic pain, swelling, discoloration, and ulceration of the affected limb [29]. In children, the risk of PTS following VTE is estimated at 10%–70% [30]. The likelihood of PTS is higher in the first 2 years of VTE, and it continues to increase over time [29]. In our study, 2 out of 5 patients (20%) with persistent VTE in the form of stasis ulcer and varicose vein developed PTS after 2 and 9 years of the initial VTE diagnosis, respectively. Further, 2 patients died as a result of massive pulmonary emboli.

The present study has several limitations. First, being a retrospective study, data collection, and subsequent analyses may be incomplete. Second, this study was conducted at a single center, and therefore the true incidence of pediatric VTE may be under- or over-estimated due to a selection bias. Finally, since VTE is a rare condition, our study population was small, and therefore the frequency of congenital thrombophilic disorders could not be estimated.

In conclusion, we observed that pediatric VTE occurred at a lower frequency in the studied Korean population than has been previously reported for Western countries. However, the clinical characteristics of VTE patients including the bimodal age distribution, underlying diseases, treatment pattern, and outcomes were comparable to those reported from the Western countries. A nationwide, multicentric study will be needed to accurately estimate the true incidence and outcome of pediatric VTE in Korea.

Go to :

Notes

This study was supported by a grant from the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (SNUBH) Research Fund (Grant number: 02-2013-047).

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Go to :

References

1. Chalmers E, Ganesen V, Liesner R, et al. Guideline on the investigation, management and prevention of venous thrombosis in children. Br J Haematol. 2011; 154:196–207. PMID: 21595646.

2. Nowak-Göttl U, Janssen V, Manner D, Kenet G. Venous thromboembolism in neonates and children--update 2013. Thromb Res. 2013; 131(Suppl 1):S39–S41. PMID: 23452739.

3. Raffini L, Huang YS, Witmer C, Feudtner C. Dramatic increase in venous thromboembolism in children's hospitals in the United States from 2001 to 2007. Pediatrics. 2009; 124:1001–1008. PMID: 19736261.

4. Setty BA, O'Brien SH, Kerlin BA. Pediatric venous thromboembolism in the United States: a tertiary care complication of chronic diseases. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012; 59:258–264. PMID: 22038730.

5. Andrew M, David M, Adams M, et al. Venous thromboembolic complications (VTE) in children: first analyses of the Canadian Registry of VTE. Blood. 1994; 83:1251–1257. PMID: 8118029.

6. van Ommen CH, Heijboer H, Büller HR, Hirasing RA, Heijmans HS, Peters M. Venous thromboembolism in childhood: a prospective two-year registry in The Netherlands. J Pediatr. 2001; 139:676–681. PMID: 11713446.

7. Schmidt B, Andrew M. Neonatal thrombosis: report of a prospective Canadian and international registry. Pediatrics. 1995; 96:939–943. PMID: 7478839.

8. Athale U, Siciliano S, Thabane L, et al. Epidemiology and clinical risk factors predisposing to thromboembolism in children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008; 51:792–797. PMID: 18798556.

9. Sandoval JA, Sheehan MP, Stonerock CE, Shafique S, Rescorla FJ, Dalsing MC. Incidence, risk factors, and treatment patterns for deep venous thrombosis in hospitalized children: an increasing population at risk. J Vasc Surg. 2008; 47:837–843. PMID: 18295440.

10. Chopra V, Anand S, Hickner A, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with peripherally inserted central catheters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013; 382:311–325. PMID: 23697825.

11. Andrew M. Developmental hemostasis: relevance to thromboembolic complications in pediatric patients. Thromb Haemost. 1995; 74:415–425. PMID: 8578498.

12. Jang MJ, Bang SM, Oh D. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in Korea: from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database. J Thromb Haemost. 2011; 9:85–91. PMID: 20942850.

13. Naess IA, Christiansen SC, Romundstad P, Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal FR, Hammerstrøm J. Incidence and mortality of venous thrombosis: a population-based study. J Thromb Haemost. 2007; 5:692–699. PMID: 17367492.

14. Newall F, Wallace T, Crock C, et al. Venous thromboembolic disease: a single-centre case series study. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006; 42:803–807. PMID: 17096717.

15. Wright JM, Watts RG. Venous thromboembolism in pediatric patients: epidemiologic data from a pediatric tertiary care center in Alabama. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011; 33:261–264. PMID: 21516021.

16. Nowak-Göttl U, von Kries R, Göbel U. Neonatal symptomatic thromboembolism in Germany: two year survey. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1997; 76:F163–F167. PMID: 9175945.

17. Andrew M, Paes B, Milner R, et al. Development of the human coagulation system in the healthy premature infant. Blood. 1988; 72:1651–1657. PMID: 3179444.

18. White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003; 107(23 Suppl 1):I4–I8. PMID: 12814979.

19. van Ommen CH, Heijboer H, van den Dool EJ, Hutten BA, Peters M. Pediatric venous thromboembolic disease in one single center: congenital prothrombotic disorders and the clinical outcome. J Thromb Haemost. 2003; 1:2516–2522. PMID: 14675086.

20. Spentzouris G, Scriven RJ, Lee TK, Labropoulos N. Pediatric venous thromboembolism in relation to adults. J Vasc Surg. 2012; 55:1785–1793. PMID: 21944920.

21. Simioni P, Sanson BJ, Prandoni P, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in families with inherited thrombophilia. Thromb Haemost. 1999; 81:198–202. PMID: 10063991.

22. Young G, Albisetti M, Bonduel M, et al. Impact of inherited thrombophilia on venous thromboembolism in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Circulation. 2008; 118:1373–1382. PMID: 18779442.

23. Tuckuviene R, Christensen AL, Helgestad J, Johnsen SP, Kristensen SR. Pediatric venous and arterial noncerebral thromboembolism in Denmark: a nationwide population-based study. J Pediatr. 2011; 159:663–669. PMID: 21596390.

24. Song KS, Park YS, Kim HK, Choi JR, Park Q. Prevalence of Arg306 mutation of the factor V gene in Korean patients with thrombosis. Haemostasis. 1998; 28:276. PMID: 10420078.

25. Ro A, Hara M, Takada A. The factor V Leiden mutation and the prothrombin G20210A mutation was not found in Japanese patients with pulmonary thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 1999; 82:1769.

26. Shen MC, Lin JS, Tsay W. Factor V Arg306 --> Gly mutation is not associated with activated protein C resistance and is rare in Taiwanese Chinese. Thromb Haemost. 2001; 85:270–273. PMID: 11246546.

27. Monagle P, Chan AK, Goldenberg NA, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in neonates and children: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012; 141(2 Suppl):e737S–e801S. PMID: 22315277.

28. Goldenberg NA, Takemoto CM, Yee DL, Kittelson JM, Massicotte MP. Improving evidence on anticoagulant therapies for venous thromboembolism in children: key challenges and opportunities. Blood. 2015; 126:2541–2547. PMID: 26500341.

30. Kumar R, Rodriguez V, Matsumoto JM, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for post thrombotic syndrome after deep vein thrombosis in children: a cohort study. Thromb Res. 2015; 135:347–351. PMID: 25528070.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download