Abstract

Background

Efforts to overcome poor outcomes in patients with adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) have focused on combining new therapeutic agents targeting immunophenotypic markers (IPMs) with classical cytotoxic agents; therefore, it is important to evaluate the clinical significance of IPMs.

Methods

Baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes of patients with adult ALL were retrospectively analyzed. The percentage of blasts expressing IPMs at diagnosis was measured by multicolor flow cytometry analysis. Samples in which ≥20% of blasts expressed an IPM were considered positive.

Results

Among the total patient population (N=230), almost all (92%) were in first or second hematological complete remission (HCR) and 54% received allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (allo-HCT). Five-year hematologic relapse-free survival (HRFS) and overall survival (OS) rates were 36% and 39%, respectively, and 45.6% and 80.5% of patients were positive for the IPMs CD20 and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), respectively. Expression of CD20, CD13, CD34, and TdT was associated with HRFS rate, and expression of CD20 and CD13 was associated with OS rate, as was the performance of allo-HCT. In multivariate analysis, positivity for CD20 (HRFS: hazard ratio [HR], 2.21, P<0.001; OS: HR, 1.63, P=0.015) and negativity for TdT (HRFS: HR, 2.30, P=0.001) were both significantly associated with outcomes. When patients were categorized into three subgroups according to positivity for CD20 and TdT, there were significant differences in HRFS and OS among the subgroups.

In adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), although initial hematological complete remission (HCR) rates are high, many patients eventually relapse and do not respond to salvage therapy, hence prognosis is poor [1]. In contrast with pediatric ALL [2], interventions to improve the outcome of adult ALL are currently lacking, with the exception of the administration of BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) for the treatment of Philadelphia-positive (Ph-pos) ALL [345].

Many adult ALL patients are ineligible for the high-dose post-remission therapy used in pediatric cases, and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) is recommended for patients in both high and standard risk groups [6]. Although allo-HCT reduces relapse rates in adult ALL via the graft-versus-leukemia effect [789], some adult patients are ineligible for allo-HCT due to old age, comorbidity, or donor availability. Recently, a combination of targeted and conventional cytotoxic agents has been suggested as a potential method to improve outcomes for adult ALL patients, and monoclonal antibodies targeting common surface molecules of ALL blast cells, including CD19 [1011], CD20 [12], and CD22 [13], are under development or have already been used in treatment. In addition to being therapeutic targets of various monoclonal antibodies, these immunophenotypic markers (IPMs) may themselves serve as useful prognostic markers of response to treatment and outcomes [14]. Therefore, analysis of the prevalence and therapeutic clinical implications of various IPMs may provide important insights beneficial to the development of improved treatments for adult ALL.

In this study, we report the results of a retrospective analysis of the prevalence and clinical implications of various IPMs, including CD20, which has been highlighted in other recent studies. The study focused on determining whether positivity for combinations of IPMs, or for IPMs with other clinical features, is a useful prognostic indicator.

Patients aged ≥18 years diagnosed with ALL or Ph-pos biphenotypic acute leukemia (BAL) in the Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, were included in this retrospective analysis. Patients were excluded from the analysis if they had at least one of the following features: diagnosis with L3 ALL (Burkitt leukemia) or chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) with lymphoid blast crisis, no results from CD19/CD20/CD22 cell surface marker analysis, or no treatment with vincristine, prednisone, and daunorubicin plus L-asparaginase (VPDL) [15] or modified VPDL-based chemotherapy [41617].

Patients were assigned to the high clinical risk group (CRG), according to the definition of the MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993 trial [6], if they met one or more of the following criteria: 1) age ≥35 years, 2) white blood cell (WBC) count at diagnosis ≥30×106/L (for B-cell) and ≥100×106/L (for T-cell), 3) presence of t(9;22) or BCR-ABL1 transcript, and 4) presence of t(4;11) or MLL-AF4 transcript. The institutional review board of Asan Medical Center approved this study (AMC-2015-0891).

Ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA)-anticoagulated bone marrow (BM) aspirates were obtained from 230 patients at the time of diagnosis. IPM expression of an ALL marker panel (CD45, CD34, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase [TdT], CD19, CD10, CD20, cytoplasmic CD22, CD2, CD3, cytoplasmic CD3, CD5, CD7, CD13, CD33, myeloperoxidase, surface immunoglobulin M [IgM], and cytoplasmic IgM) was assessed within 24 hours of sample collection. BM aspirate (100 µL) was incubated with 8 µL of each fluorescence-conjugated monoclonal antibody for 20 minutes at room temperature. Nuclear (TdT) and cytoplasmic antigens (cytoplasmic CD22, CD3, IgM, and myeloperoxidase) were incubated with specific antibodies after a permeabilization process, using permeability reagents, and erythrocytes were lysed using lysing solution. Isotypic antibodies were used as negative controls in separate tubes. After washing with 2 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixing in 500 µL of 1% phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-paraformaldehyde, flow cytometry was performed using the FACSCanto II flow cytometry system (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and analyzed using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). Twenty thousand nucleated cells were acquired per tube, and leukemic blasts were isolated using CD45/side scatter gating. The expression level (%) of each IPM was estimated by comparison with the isotypic control, and positivity was defined as ≥20% leukemic cells staining positive for an IPM among total leukemic blasts. All antibodies were purchased from Becton Dickinson (BD Biosciences).

All patients received induction chemotherapy with VPDL (for Ph-negative ALL) or VPD plus BCR-ABL1 TKIs (for Ph-pos ALL). Those who were diagnosed and received induction chemotherapy after June 2005 were enrolled in the prospective study by the Adult ALL Working Party of the Korean Society of Hematology (June 2005 to May 2010) and were treated with a modified VPDL regimen, to evaluate the feasibility of daunorubicin dose escalation during induction for patients <65 years of age [16].

BCR-ABL1 TKIs were administered to patients with Ph-pos ALL from 2001, and patients enrolled in two prospective studies to evaluate the effectiveness of TKIs were included in this analysis. In the first study, conducted from 2005 until 2008, patients received imatinib (600 mg per day) plus multiagent chemotherapy [17], and in the second study (2009 until 2011), patients were treated with nilotinib (400 mg twice a day) plus multiagent chemotherapy [4]. BCR-ABL1 TKIs were changed to the second-line agent, including dasatinib, when patients experienced intolerance to or failure with the first-line agent.

After achieving HCR, patients either received a course of consolidation chemotherapy or, if it was feasible and a suitable donor was available, were considered for allo-HCT. Allo-HCT could be performed at any time after the achievement of HCR. Acceptable donors included matched siblings, fully or partially matched unrelated donors, and haploidentical familial (familial mismatched) donors. Patients undergoing allo-HCT received either myeloablative conditioning (busulfan plus cyclophosphamide or fludarabine; patients <55 years old) or reduced-intensity conditioning, consisting of a combination of busulfan, fludarabine, and antithymocyte globulin (patients ≥55 years old, or with comorbidities). Total body irradiation was not used for conditioning. Stem cells were collected either from BM or from granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-mobilized peripheral blood (PB).

Positivity for each IPM was defined as expression on ≥20% of blasts. Patients were dichotomized according to positivity for each IPM.

Characteristics of each group were summarized using descriptive statistics, and between-group differences were assessed by the t-test for normally distributed clinical characteristics, the Mann-Whitney U-test for non-normally distributed features, and Fisher's exact test for nominal variables.

Hematologic relapse (HREL) was defined as the presence of >5% lymphoblasts in the total mononuclear cells in BM aspirate, or the infiltration of lymphoblasts in extramedullary organs. Hematologic relapse-free survival (HRFS) time was measured from the date of HCR to the date of non-relapse mortality (NRM) or HREL. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the diagnosis of ALL to the date of last follow-up or death.

Differences in HCR rates between subgroups defined by positivity for IPMs were compared by logistic regression. Differences in HRFS and OS rates were compared using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test, and by Cox proportional hazards analysis. Variables with P values<0.1 in univariate analysis were included in multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis. All statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

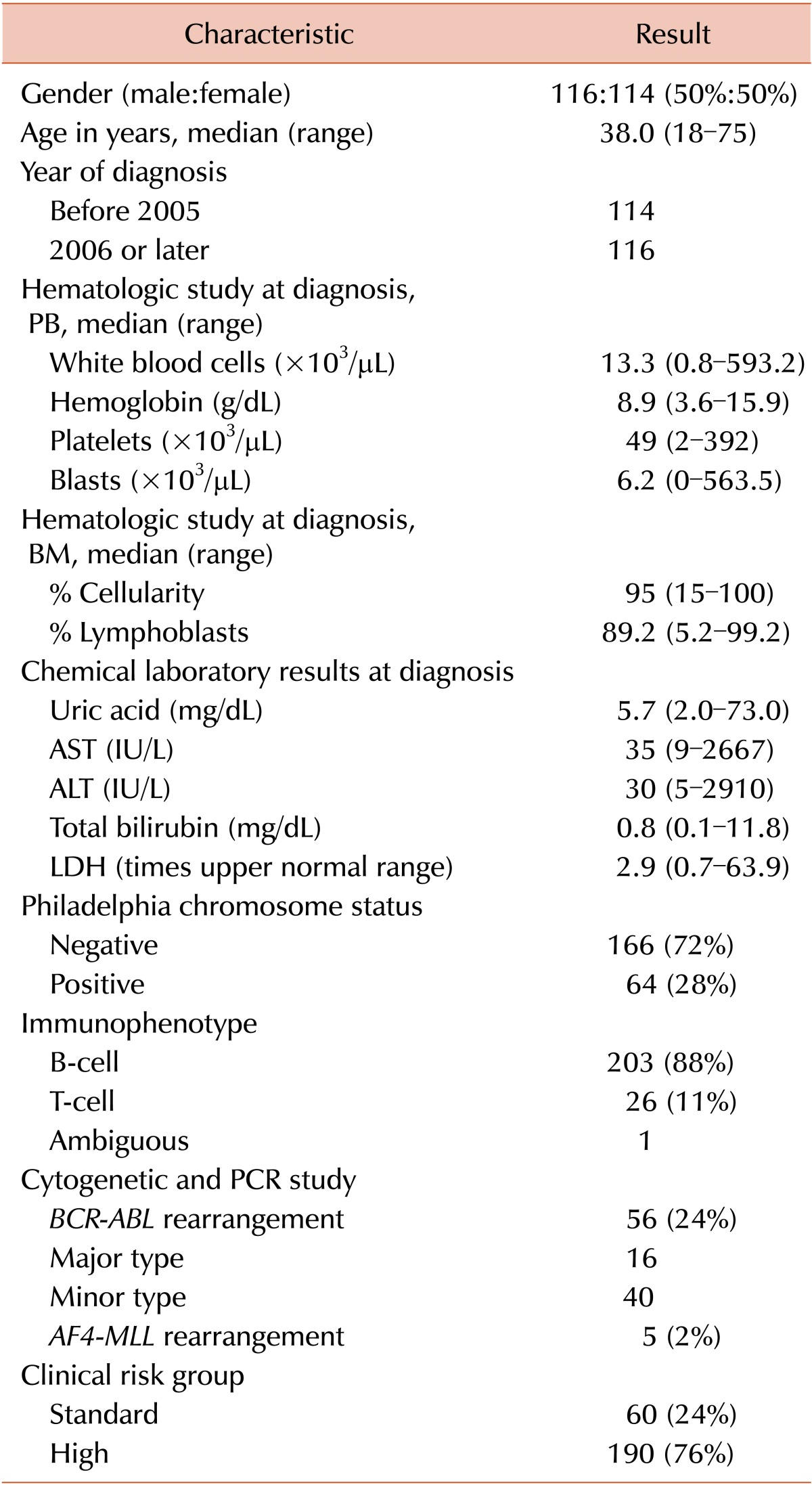

Baseline characteristics and treatment outcomes of 230 patients who were diagnosed with ALL or Ph-pos BAL from 1994 until 2011 at Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, and met the inclusion criteria are provided in Table 1. Twenty-eight percent of patients were diagnosed with Ph-pos ALL and 76% were classified into the high CRG.

All patients received VPDL- or modified VPDL-based chemotherapeutic cycles, and BCR-ABL1 TKIs were combined with cytotoxic agents for 37 (58%) of 64 patients with Ph-pos ALL. The BCR-ABL1 TKIs used were imatinib (N=23), nilotinib (N=13), and dasatinib (N=1).

The HCR rate for all patients was 92%, and the rate did not differ between patients with Ph-negative and Ph-pos ALL. A total of 124 patients (54%) underwent allo-HCT in first HCR (N=99), second HCR (N=9), and relapsed/refractory (N=16) status, respectively.

After a median of 45.4 months of follow-up of surviving patients (range, 1.4-203.0), the 2-year and 5-year HRFS rates were 48% and 36%, respectively, and the median HRFS time was 20.2 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 9.5-30.9) among patients who achieved HCR. The 2-year and 5-year OS rates of all patients included in this analysis were 57% and 39%, respectively, and the median OS time was 30.8 months (95% CI, 23.3-38.3).

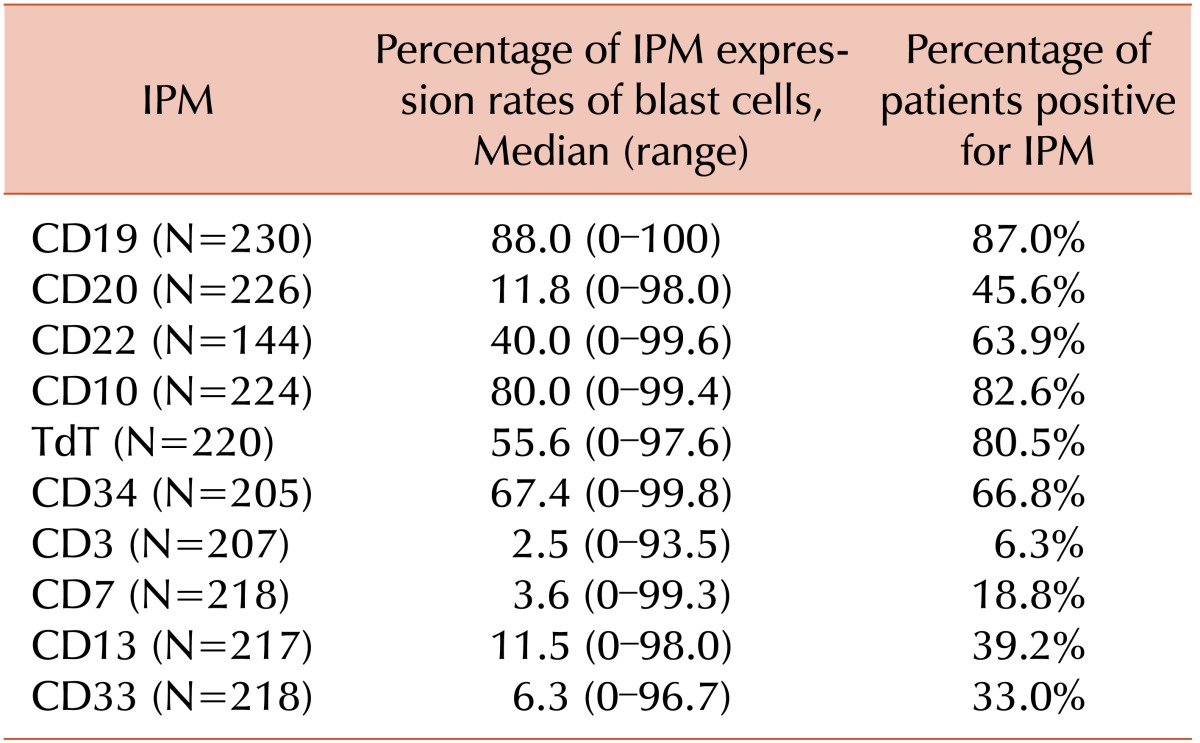

Table 2 shows the expression rates of major ALL IPMs in samples from patients included in this study. The majority of patient samples were positive for CD19 and CD22 (87.0% and 63.9%, respectively). Among 226 and 220 evaluable patients, 45.6% and 80.5% were CD20- and TdT-positive, respectively.

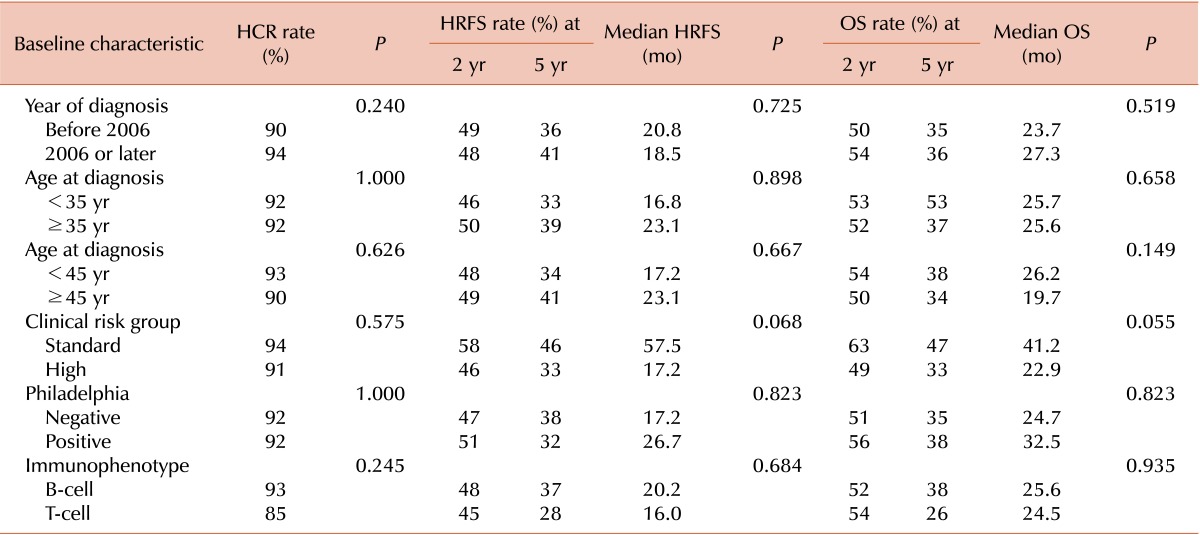

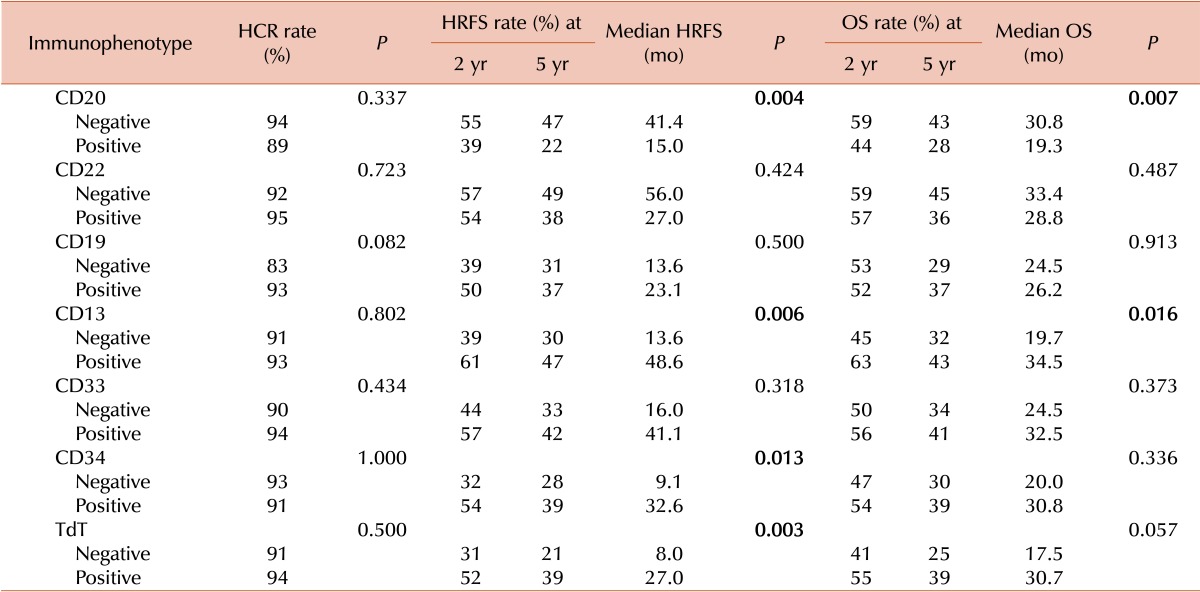

None of the established prognostic factors or IPMs were associated with the HCR rate (Tables 3, 4). In contrast, positivity for CD20, CD13, CD34, and TdT was associated with the HRFS rate, and positivity for CD20 and CD13 was strongly associated with the OS rate (Table 4). When the outcomes were analyzed among patients who achieved HCR, 5-year HRFS (40% vs. 32%, P=0.002) and OS rates (46% vs. 31%, P=0.002) were significantly higher among those who received allo-HCT than among those who did not.

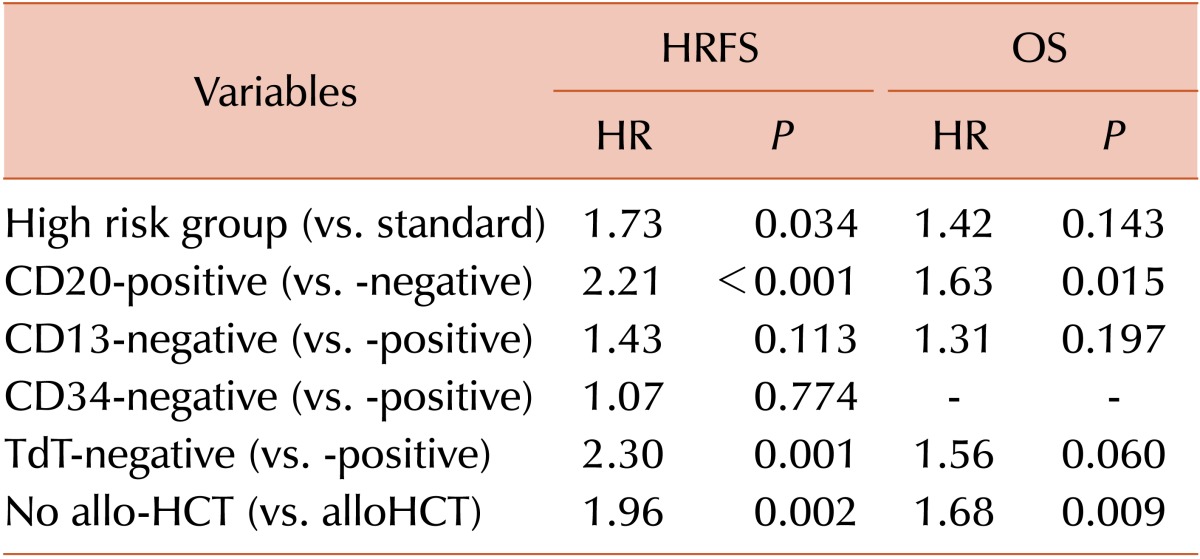

We assessed the prognostic value of IPMs by multivariate analysis including variables from the univariate analysis with P values<0.1. Positivity for CD20 and negativity for TdT were both significantly associated with HRFS and OS rates, as were CRG and performance of allo-HCT (Table 5).

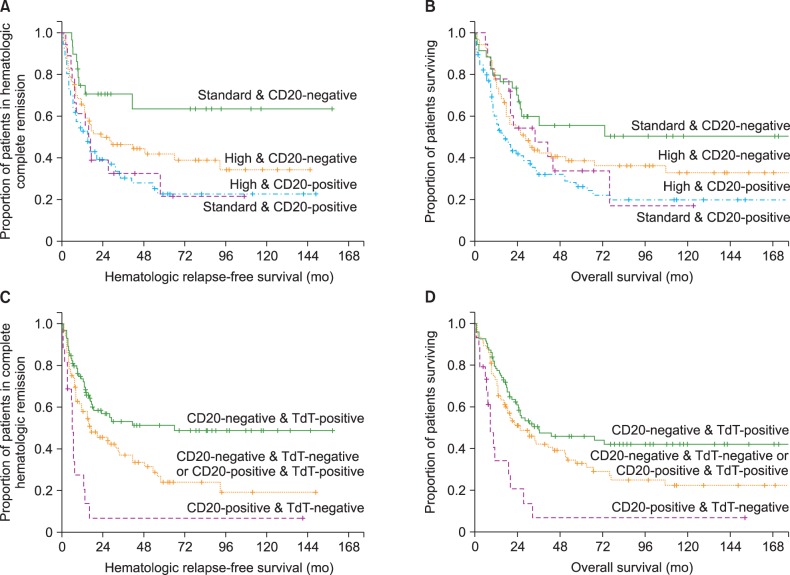

We categorized patients according to CRG status and CD20 and TdT positivity, which were all significantly associated with outcome variables on multivariate analysis. Initially, patients were categorized into four subgroups according to CRG and CD20 positivity: group 1, standard CRG and CD20-negative; group 2, high CRG and CD20-negative; group 3, standard CRG and CD20-positive; and group 4, high CRG and CD20-positive. There were significant differences between the groups in median values for HRFS, which were "not reached", 23.1 months, 15.5 months, and 14.7 months for groups 1-4, respectively (P=0.001). Median values for OS also differed significantly at "not reached", 28.4 months, 33.9 months, and 16.6 months for subgroups 1-4, respectively (P=0.001; Fig. 1A, B).

Next, patients were categorized into three subgroups according to positivity for CD20 and TdT: group 1, CD20-negative and TdT-positive; group 2, CD20-negative and TdT-negative or CD20-positive and TdT-positive; and group 3, CD20-positive and TdT-negative. There were also significant differences between these groups in median HRFS (65.8 months, 16.8 months, and 6.0 months, respectively; P<0.001) and median OS (36.1 mo, 25.4 mo, and 9.0 mo, respectively; P<0.001) (Fig. 1C, D).

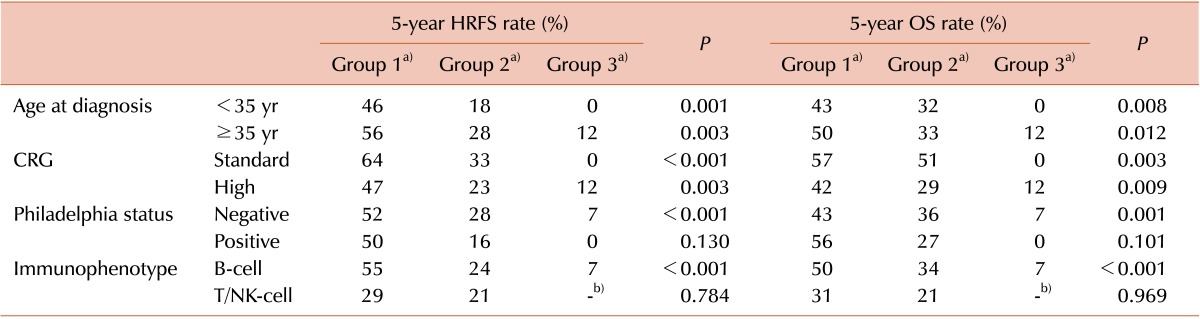

The prognostic significance of stratification by positivity for CD20 and TdT was evaluated and validated for each patient cohort (Table 6).

Stratification by positivity for CD20 and TdT demonstrated discriminative power in both groups based on age at diagnosis (<35 years and ≥35 years) and in high and standard CRG patients. Positivity for CD20 and TdT were also prognostic in Ph-negative and B-cell patient cohorts, whereas these markers were not significantly associated with prognosis in patients with Ph-pos and T-cell ALL.

The prognostic significance of IPMs has been described in a number of previous reports [1214181920212223]. The current study demonstrates that positivity for CD20, TdT, CD34, and CD13 (defined as expression on ≥20% of blasts) was associated with HRFS and OS rates in univariate analysis. In addition, in multivariate analyses, CRG status, CD20 positivity, and TdT negativity were associated with HRFS, and CRG status, CD20 positivity, and CD13 and TdT negativity were associated with OS. Finally, risk stratification by positivity for combinations of IPMs was prognostic, with stratification into three subgroups according to CD20 and TdT status demonstrating the greatest discriminatory power.

The prognostic significance of CD20 expression has been described in several previous reports. Thomas et al. demonstrated that patients with CD20 positivity had a higher incidence of relapse and inferior long-term survival rates compared to those who were negative for this marker [14]. Another report by the same group showed that overall outcomes, including incidence of relapse and long-term survival, were improved when patients with CD20 positivity were treated with rituximab plus combination chemotherapy [12]. In addition, another prospective observational study showed that allo-HCT overcame the adverse prognostic impact of CD20 expression in ALL [18]. These results suggest that CD20 expression is prognostic for outcomes and predictive for response to treatment with rituximab and/or allo-HCT in adult patients with ALL. The results of the present study were consistent with these previous reports.

In contrast, the prognostic significance of TdT has not been fully described in previous reports. A few reports have correlated the presence during remission of TdT-positive cells in PB with relapse [24], or of TdT-positive cells in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in ALL with CSF infiltration of leukemic blasts [25]. In the current study, we demonstrate that positivity for TdT, defined as ≥20% of BM aspirate mononuclear cells staining for the marker, was correlated with good prognosis in ALL.

When patients were classified into four subgroups according to positivity for CD20 expression and CRG status, CRG status retained its prognostic value among CD20-negative patients, whereas it was not prognostically significant for the CD20-positive group. This suggests that CD20 expression can be considered a meaningful and independent prognostic factor, irrespective of CRG, and that treatment with agents targeting CD20, such as rituximab, is warranted in combination with standard cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents and may improve the outcome of CD20+ ALL.

In this study, the three-group stratification system by positivity for CD20 and TdT expression was prognostic for the whole patient group and for cohorts classified by age at diagnosis, CRG, Philadelphia status, and immunophenotype (B- vs. T-cell). Risk stratification by positivity for IPM expression is objective and highly reproducible, and could be applied in clinical trials or to suggest tailored therapy.

The limitations of the current study are its retrospective design and the fact that it was restricted to patients treated in a single center over a relatively long period of time (17 years). Also, although the inclusion criteria specified treatment with one of two homogeneous regimens (VPDL or modified VPDL), the post-remission therapies, including conditioning, stem cell source, and donor type for allo-HCT, were heterogeneous. In addition, a number of patients among those with Ph-pos ALL did not receive treatment with a BCR-ABL1 TKI, indicating that the patient population was not directly comparable to those undergoing current treatment regimens. Although the number of patients with T-cell or ambiguous lineage ALL was relatively small (N=27, 12%), they were included for the survival analysis including univariate and multivariate analysis, which requires a consideration during the interpretation of the results of the current study that CD20 is a B-lineage specific antigen, and the previous studies on CD20 were conducted only among patients with B-lineage ALL.

In conclusion, our results indicate that positivity for CD20 and TdT expression, in addition to CRG and the performance of allo-HCT, is an important prognostic indicator in adult ALL. A prospective observational study is highly warranted to confirm the prognostic significance of these IPMs, and a well-designed prospective study is planned to combine new agents targeting these IPMs with classical cytotoxic therapies and determine whether this strategy can effectively overcome the poor outcomes characteristic of adult ALL.

References

1. Gökbuget N, Stanze D, Beck J, et al. Outcome of relapsed adult lymphoblastic leukemia depends on response to salvage chemotherapy, prognostic factors, and performance of stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2012; 120:2032–2041. PMID: 22493293.

2. Hallböök H, Gustafsson G, Smedmyr B, et al. Treatment outcome in young adults and children >10 years of age with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Sweden: a comparison between a pediatric protocol and an adult protocol. Cancer. 2006; 107:1551–1561. PMID: 16955505.

3. Fielding AK, Rowe JM, Buck G, et al. UKALLXII/ECOG2993: addition of imatinib to a standard treatment regimen enhances long-term outcomes in Philadelphia positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2014; 123:843–850. PMID: 24277073.

4. Kim DY, Joo YD, Lim SN, et al. Nilotinib combined with multiagent chemotherapy for newly diagnosed Philadelphiapositive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2015; 126:746–756. PMID: 26065651.

5. Ravandi F, O'Brien S, Thomas D, et al. First report of phase 2 study of dasatinib with hyper-CVAD for the frontline treatment of patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010; 116:2070–2077. PMID: 20466853.

6. Goldstone AH, Richards SM, Lazarus HM, et al. In adults with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the greatest benefit is achieved from a matched sibling allogeneic transplantation in first complete remission, and an autologous transplantation is less effective than conventional consolidation/maintenance chemotherapy in all patients: final results of the International ALL Trial (MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993). Blood. 2008; 111:1827–1833. PMID: 18048644.

7. Cho BS, Lee S, Kim YJ, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation is a potential therapeutic approach for adults with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia in remission: results of a prospective phase 2 study. Leukemia. 2009; 23:1763–1770. PMID: 19440217.

8. Eom KS, Shin SH, Yoon JH, et al. Comparable long-term outcomes after reduced-intensity conditioning versus myeloablative conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation for adult high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia in complete remission. Am J Hematol. 2013; 88:634–641. PMID: 23620000.

9. Mohty M, Labopin M, Volin L, et al. Reduced-intensity versus conventional myeloablative conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation for patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a retrospective study from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Blood. 2010; 116:4439–4443. PMID: 20716774.

10. Zugmaier G, Gökbuget N, Klinger M, et al. Long-term survival and T-Cell kinetics in adult patients with relapsed/refractory B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia who achieved minimal residual disease response following treatment with Anti-CD19 BiTE® antibody construct blinatumomab. Blood. 2015; [Epub ahead of print].

11. Topp MS, Gökbuget N, Stein AS, et al. Safety and activity of blinatumomab for adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015; 16:57–66. PMID: 25524800.

12. Thomas DA, O'Brien S, Faderl S. Chemoimmunotherapy with a modified hyper-CVAD and rituximab regimen improves outcome in de novo Philadelphia chromosome-negative precursor B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28:3880–3889. PMID: 20660823.

13. Jabbour E, O'Brien S, Huang X. Prognostic factors for outcome in patients with refractory and relapsed acute lymphocytic leukemia treated with inotuzumab ozogamicin, a CD22 monoclonal antibody. Am J Hematol. 2015; 90:193–196. PMID: 25407953.

14. Thomas DA, O'Brien S, Jorgensen JL, et al. Prognostic significance of CD20 expression in adults with de novo precursor B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2009; 113:6330–6337. PMID: 18703706.

15. Linker CA, Levitt LJ, O'Donnell M, Forman SJ, Ries CA. Treatment of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia with intensive cyclical chemotherapy: a follow-up report. Blood. 1991; 78:2814–2822. PMID: 1835410.

16. Lee SM, Lee WS, Shin HJ, et al. Escalated daunorubicin dosing as an induction treatment for Philadelphia-negative adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2013; 92:1101–1110. PMID: 23558905.

17. Lim SN, Joo YD, Lee KH, et al. Long-term follow-up of imatinib plus combination chemotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2015; 90:1013–1020. PMID: 26228525.

18. Bachanova V, Sandhu K, Yohe S, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation overcomes the adverse prognostic impact of CD20 expression in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2011; 117:5261–5263. PMID: 21403127.

19. Thomas DA. Rituximab as therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2010; 8:168–171. PMID: 20400931.

20. Maury S, Huguet F, Leguay T, et al. Adverse prognostic significance of CD20 expression in adults with Philadelphia chromosome-negative B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2010; 95:324–328. PMID: 19773266.

21. Seegmiller AC, Kroft SH, Karandikar NJ, McKenna RW. Characterization of immunophenotypic aberrancies in 200 cases of B acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009; 132:940–949. PMID: 19926587.

22. Jeha S, Behm F, Pei D, et al. Prognostic significance of CD20 expression in childhood B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2006; 108:3302–3304. PMID: 16896151.

23. Pituch-Noworolska A, Hajto B, Mazur B, et al. Expression of CD20 on acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells in children. Neoplasma. 2001; 48:182–187. PMID: 11583286.

24. Hetherington ML, Huntsman PR, Smith RG, Buchanan GR. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-containing peripheral blood mononuclear cells during remission of acute lymphoblastic leukemia: low sensitivity and specificity prevent accurate prediction of relapse. Leuk Res. 1987; 11:537–543. PMID: 3474480.

25. van Wering ER, Veerman AJ, van der Linden-Schrever BE. Diagnosis of meningeal involvement in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: cytomorphology and TdT. Eur J Haematol. 1988; 40:250–255. PMID: 3281860.

Fig. 1

Difference in outcomes according to clinical parameters and immunophenotype expression. (A) HRFS by CRG and CD20 positivity. (B) OS by CRG and CD20 positivity. (C) HRFS by CD20 and TdT positivity. (D) OS by CD20 and TdT positivity

Abbreviations: HRFS, hematologic relapse-free survival; CRG, clinical risk group; OS, overall survival; TdT, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase.

Table 3

Univariate analysis of the prognostic values of baseline characteristics for hematological complete remission rate and time-to-event variables.

Table 4

Univariate analysis of the prognostic values of immunophenotype for hematological complete remission rate and time-to-event variables.

Table 5

Multivariate analysis of the prognostic value of baseline characteristics, IPMs, and performance of allo-HCT for time-to-event variables.

Table 6

Differences in outcomes according to IPM subgroups among patient cohorts.

a)Group 1, CD20-negative and TdT-positive; group 2, CD20-negative and TdT-negative, or CD20-positive and TdT-positive; group 3, CD20-positive and TdT-negative. b)Indicate that no patients were included in that subgroup.

Abbreviations: IPM, immunophenotypic marker; HRFS, hematologic relapse-free survival; OS, overall survival; CRG, clinical risk group; NK-cell, natural killer cell; TdT, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download