Abstract

Background

Among the currently available prognostic models for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), we investigated to determine which is most adoptable for DLBCL patients treated with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) followed by upfront autologous stem cell transplantation (auto-SCT).

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated survival differences among risk groups based on the International Prognostic Index (IPI), the age-adjusted IPI (aaIPI), the revised IPI (R-IPI), and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network IPI (NCCN-IPI) at diagnosis in 63 CD20-positive DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP followed by upfront auto-SCT.

Results

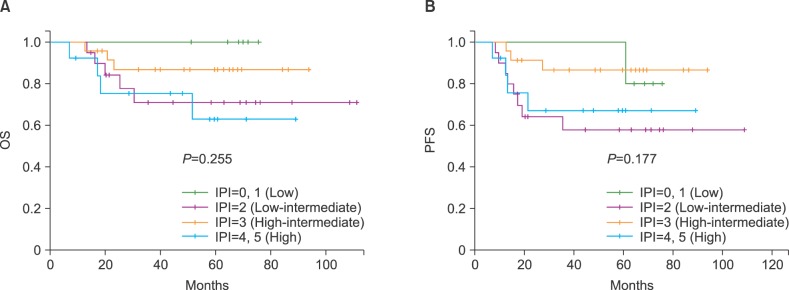

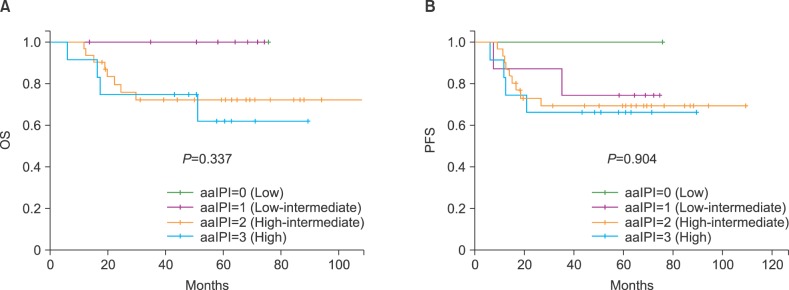

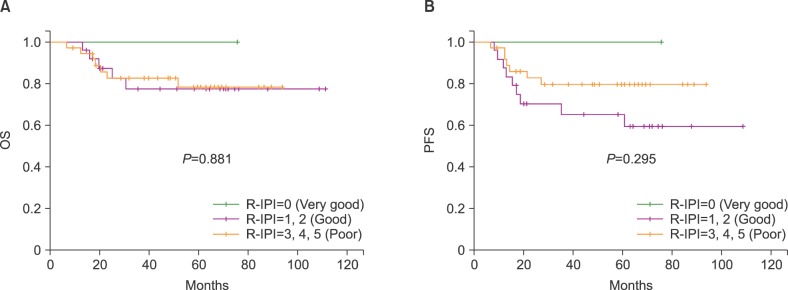

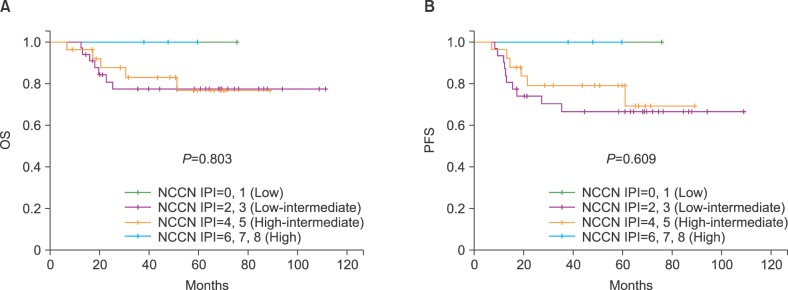

At the time of auto-SCT, 74.6% and 25.4% of patients had achieved complete remission and partial remission after R-CHOP, respectively. As a whole, the 5-year overall (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) rates were 78.8% and 74.2%, respectively. The 5-year OS and PFS rates according to the IPI, aaIPI, R-IPI, and NCCN-IPI did not significantly differ among the risk groups for each prognostic model (P-values for OS: 0.255, 0.337, 0.881, and 0.803, respectively; P-values for PFS: 0.177, 0.904, 0.295, and 0.609, respectively).

Prior to the rituximab era, the International Prognostic Index (IPI) and the age-adjusted IPI (aaIPI) were developed by the International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project to predict long-term survival for patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) [1]. Since the advent of rituximab, Sehn et al. have proposed that the revised IPI (R-IPI) is a better predictor for 4-year progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients treated with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) [2]. In addition, clinical data from the seven National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) member institutions demonstrated that the NCCN-IPI better discriminated low and high risk subgroups than the IPI for patients with DLBCL treated with rituximab-containing chemotherapy [3].

We confront uncertainty regarding the prognostic model that can differentiate the high risk group from the low risk group for patients with DLBCL treated with R-CHOP followed by upfront autologous stem cell transplantation (auto-SCT). Previously, we showed that the 5-year OS and PFS rates did not differ between the risk groups according to the aaIPI and R-IPI [4]. In this study, we aimed to determine which among the currently available prognostic models is most adoptable for DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP followed by upfront auto-SCT.

Data were collected from the Korean Blood and Marrow Transplant Registry (KBMTR). The KBMTR is a voluntary organization comprised of 43 transplantation centers located in South Korea. The Transplant Registration Committee requires participating centers to submit detailed data from consecutive patients to the KBMTR. Informed consent is obtained on-site according to KBMTR regulations. The KBMTR database was used to identify adult patients with DLBCL who underwent upfront auto-SCT while in complete remission (CR) or partial remission (PR) after R-CHOP chemoimmunotherapy between January of 2005 and March of 2014. Additional data were obtained from each center to complete this study.

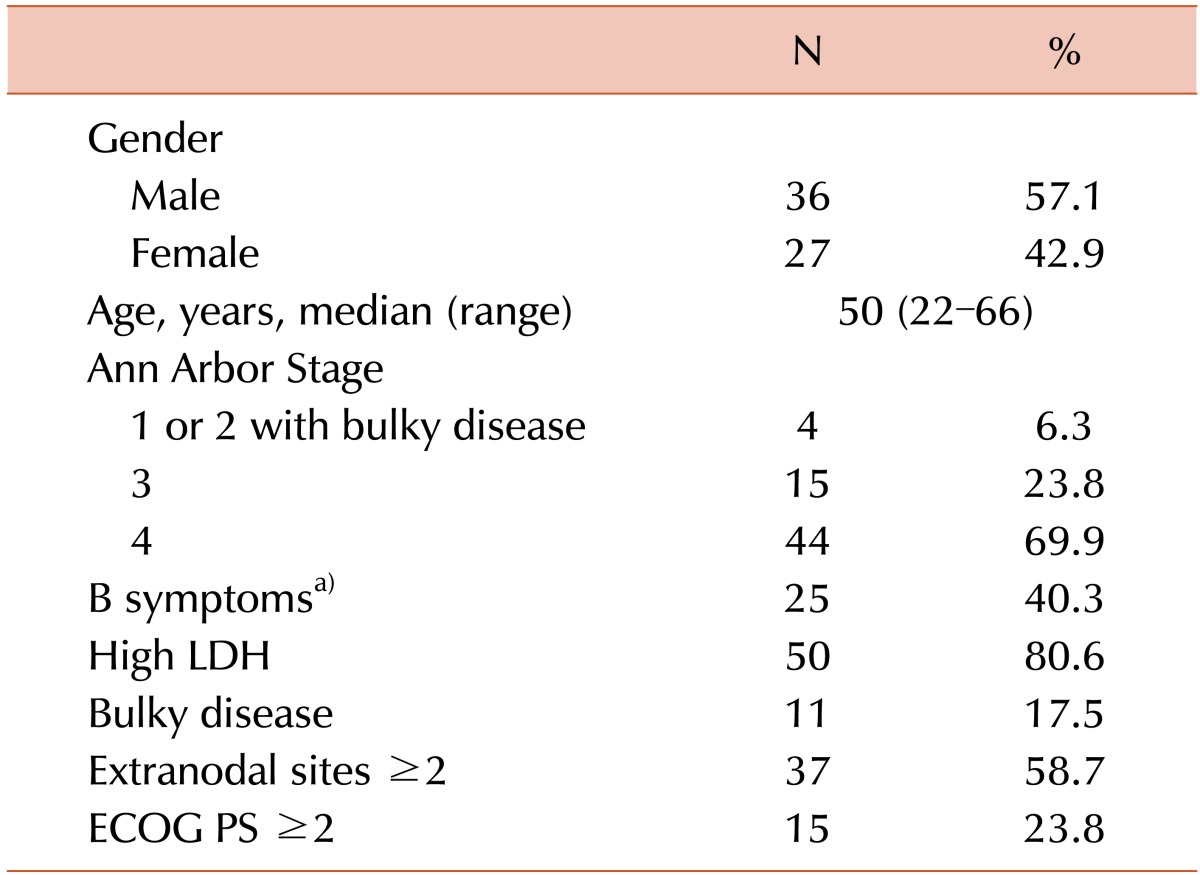

We analyzed data obtained from 63 CD20-positive DLBCL patients who underwent R-CHOP therapy followed by high-dose consolidation therapy with autologous stem cell rescue between January of 2005 and March of 2014 as reported to the KBMTR by 14 centers. Adult patients aged ≥20 years were included. In Korea, the majority of medical expenses are covered and tightly regulated by the National Health Insurance System. All types of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, including auto-SCT, are reviewed in advance by the Health Care Review and Evaluation Committee. The regulations allow auto-SCT for patients ≤65 years old when their diseases are considered high risk. Therefore, the majority of patients enrolled in this study were ≤65 years old and having Ann Arbor stage III or IV disease. Four stage I or II patients with bulky disease underwent upfront auto-SCT because their diseases were considered advanced. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Konkuk University Medical Center.

The 2007 revised guidelines of the International Harmonization Project were adopted to describe the response criteria for DLBCL [5]. CR was defined as the complete disappearance of all detectable clinical evidence of disease and disease-related symptoms if these were present before therapy. PR was defined as a ≥50% decrease in the sum of the product of the diameters (SPD) of up to 6 of the largest dominant nodes or nodal masses. Stable disease (SD) was defined as a case that failed to attain the criteria needed for CR or PR but did not fulfill those for progressive disease (PD). OS was defined as the time interval from the date of diagnosis to the date of death as a result of any cause or to the last follow-up. PFS was defined as the time interval from the date of diagnosis to the date of lymphoma progression, relapse from CR, or death as a result of any cause.

The differences in the categorical variables among the study groups were analyzed with Pearson's chi-square test and Fisher's exact test. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method and the confidence intervals were calculated using the standard error. The differences in survival among the groups with respect to variables were analyzed with the log-rank test. The P-values reported were 2-sided; a P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

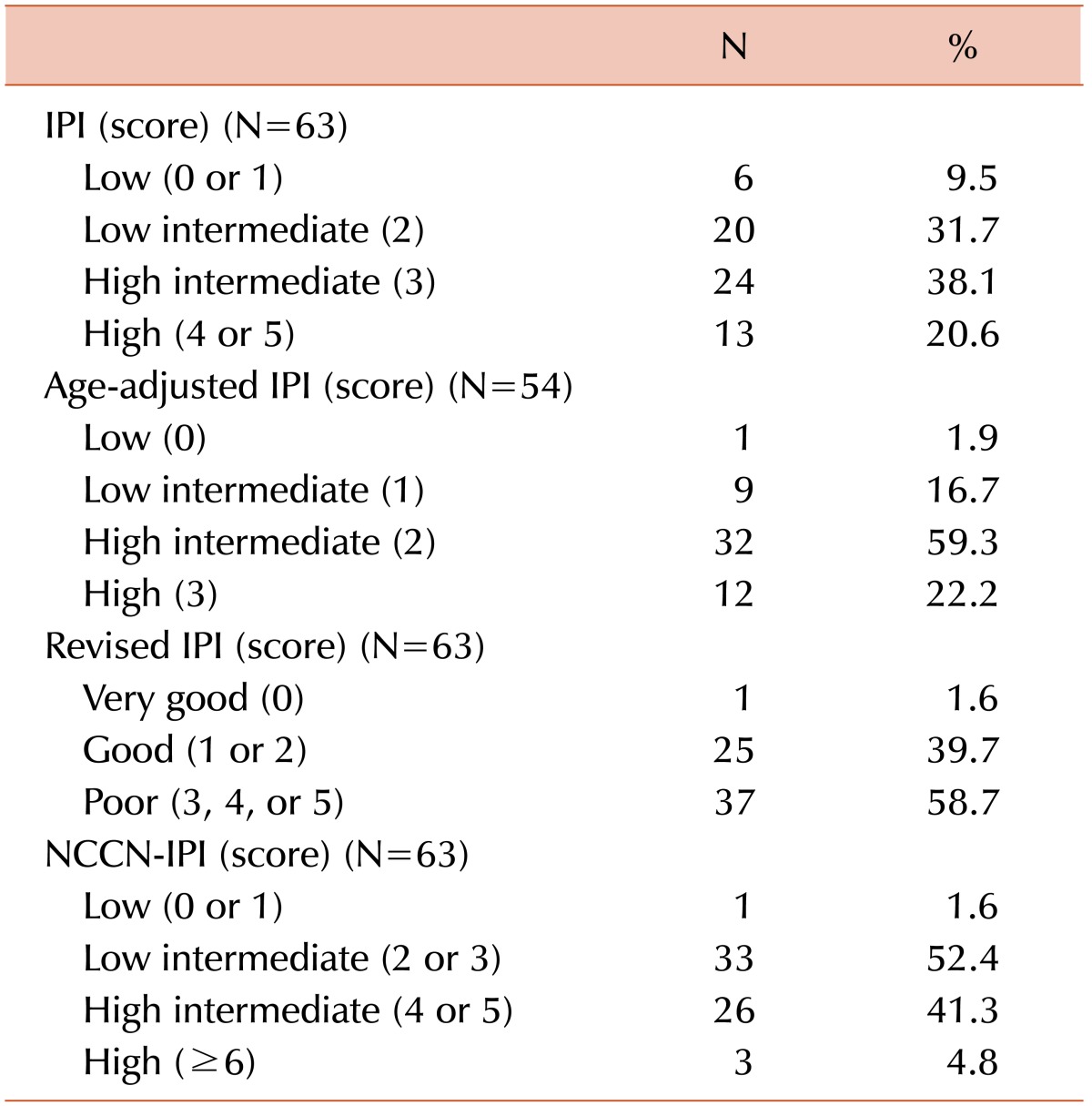

The patient and disease characteristics at the time of diagnosis are summarized in Table 1. A total of 63 patients were evaluated in the study. The patients were classified as stage I/II with bulky disease (6.3%) or stage III/IV (93.7%). Bulky disease was defined by the presence of one of the following 2 findings: (1) an abdominal node or nodal mass with a largest dimension of ≥10 cm as determined by an imaging study or (2) a mediastinal mass with a maximum width equal to or greater than one-third of the internal transverse diameter of the thorax at the T5/6 level as determined by a imaging study. At diagnosis, the IPI, R-IPI, and NCCN-IPI were available for 63 patients; however, the aaIPI was only available for 54 patients due to the age criteria. The numbers and percentages of patients classified into the risk groups of each prognostic model (IPI, aaIPI, R-IPI, and NCCN-IPI) are documented in Table 2.

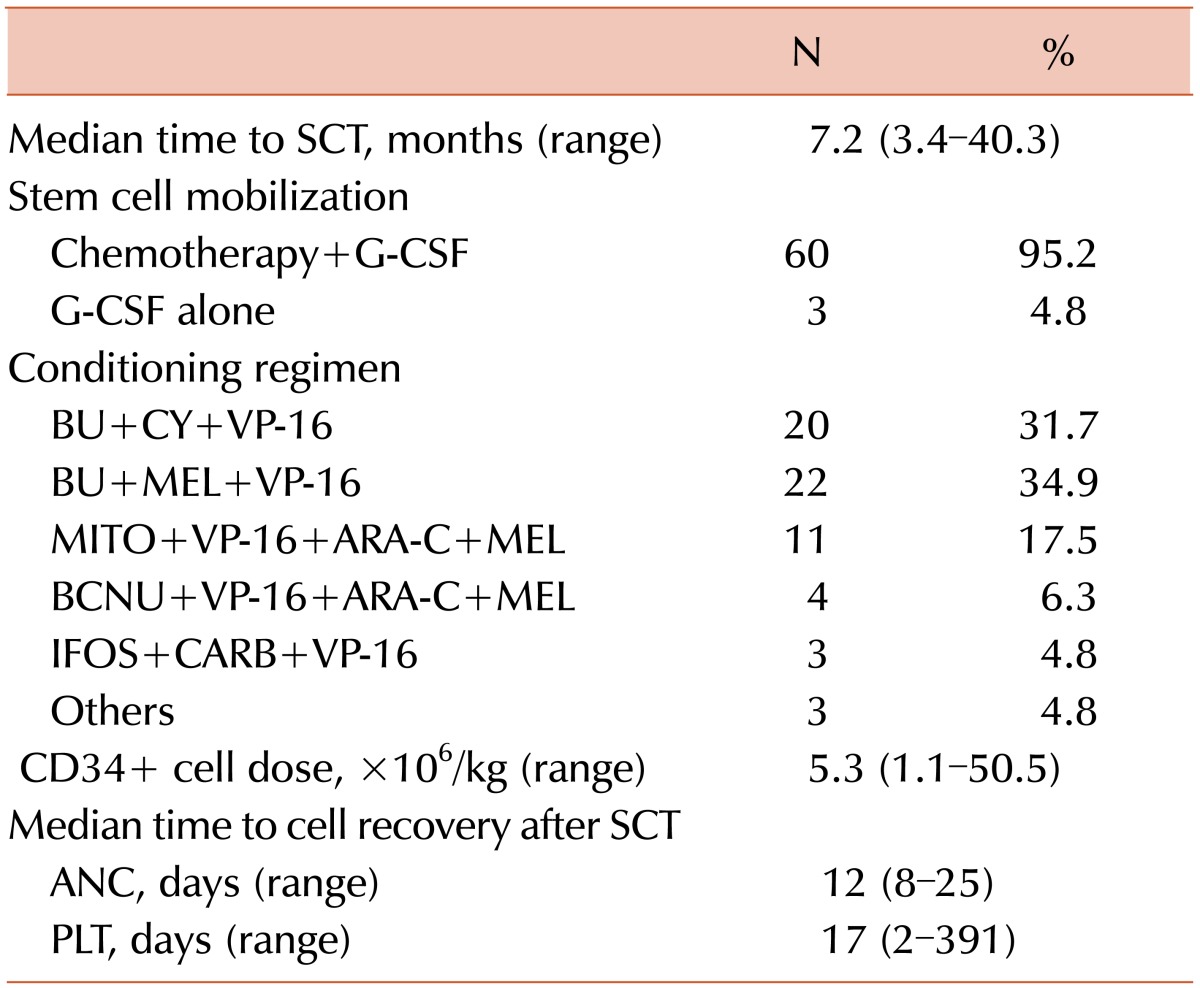

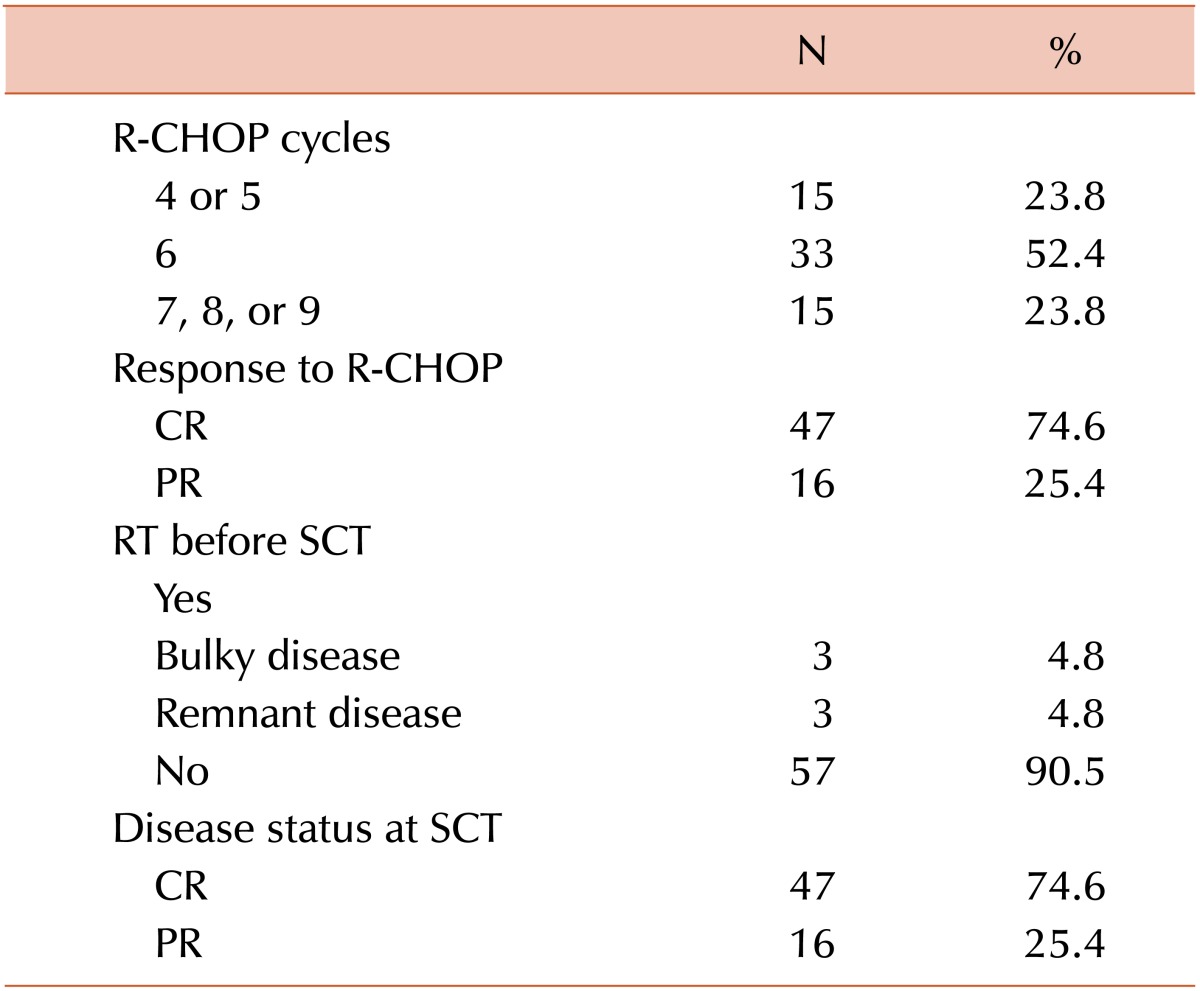

The treatments received by patients before auto-SCT and the transplantation characteristics are shown in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. The CR and PR rates following R-CHOP therapy were 74.6% and 25.4%, respectively. Six patients received involved field radiotherapy (IFRT) for bulky disease or remnant lymphoma prior to auto-SCT. One of the 6 patients receiving IFRT experienced an upgrade in response from PR to CR. However, the overall response rates were not improved at the time of auto-SCT. The median time from diagnosis to auto-SCT was 7.2 months (range, 3.4-40.3 months).

The median durations of follow-up after diagnosis and auto-SCT for all enrolled patients were 57.3 months (range, 6.3-110.7 months) and 46.3 months (range, 0.4-102.1 months), respectively. The median durations of follow-up after diagnosis and auto-SCT for the surviving patients were 60.2 months (range, 8.6-110.7 months) and 53.2 months (range, 3.6-102.1 months), respectively. During the follow-up period, 16 patients eventually relapsed after auto-SCT. Four patients died of pneumonia or bacteremia, and 8 died of lymphoma relapse. The 5-year OS and PFS rates were 78.8±5.5% and 74.2±5.8%, respectively.

The 5-year OS rates of the patients in the low (N=6), low intermediate (N=20), high intermediate (N=24), and high (N=13) risk groups were 100%, 71.2±11.0%, 86.7±7.2%, and 62.9±15.4%, respectively (P=0.255; Fig. 1A). The 5-year PFS rates of the patients in the same categories were 80±17.9%, 57.9±11.5%, 86.5±7.3%, and 67.1±13.5%, respectively (P=0.177; Fig. 1B).

We reclassified the IPI risk groups into 2 groups: low and low intermediate vs. high intermediate and high. The 5-year OS rates of the patients in the low/low intermediate (N=26) and high intermediate/high (N=37) risk groups were 78.7±8.5% and 78.5±7.4%, respectively (P=0.997). The 5-year PFS rates of the patients in the same categories were 66.8±9.7% and 79.7±6.9%, respectively (P=0.186).

The 5-year OS rates of patients in the low (N=1), low intermediate (N=9), high intermediate (N=32), and high (N=12) risk groups were 100%, 100%, 72.6±8.3%, and 62.5±15.5%, respectively (P=0.337; Fig. 2A). The 5-year PFS rates of the patients in the same categories were 100%, 75.0±15.3%, 69.6±8.5%, and 66.7±1.36%, respectively (P=0.904; Fig. 2B).

We reclassified the aaIPI risk groups into 2 groups: low and low intermediate vs. high intermediate and high. The 5-year OS rates of patients in the low/low intermediate (N=10) and high intermediate/high (N=44) risk groups were 100% and 70.2±7.3%, respectively (P=0.078). The 5-year PFS rates of the patients in the same categories were 77.8±13.9% and 68.8±7.2%, respectively (P=0.582).

The 5-year OS rates of the patients in the very good (N=1), good (N=25), and poor (N=37) risk groups were 100%, 77.7%, and 78.5±7.4%, respectively (P=0.881; Fig. 3A). The 5-year PFS rates of the patients in the same categories were 100%, 65.3±10.0%, and 79.7±6.9%, respectively (P=0.295; Fig. 3B).

We reclassified the R-IPI risk groups into 2 groups: very good and good vs. poor. The 5-year OS rates of the patients with very good/good (N=26) and poor risk (N=37) were 78.7±8.5% and 78.5±7.4%, respectively (P=0.977). The 5-year PFS rates of the patients in the same categories were 66.8±10.3% and 79.7±6.9%, respectively (P=0.186).

The 5-year OS rates of the patients with low (N=1), low intermediate (N=33), high intermediate (N=26), and high risk (N=3) were 100%, 77.3±7.6%, 76.6±9.5%, and 100%, respectively (P=0.803; Fig. 4A). The 5-year PFS rates of the patients in the same categories were 100%, 66.6±8.7%, 79.3±8.3%, and 100%, respectively (P=0.609; Fig. 4B).

We reclassified the NCCN-IPI risk groups into 2 groups: low and low intermediate vs. high intermediate and high. The 5-year OS rates of the patients with low/low intermediate (N=34) and high intermediate/high risk (N=29) were 78.0±7.4% and 78.9±8.7%, respectively (P=0.742). The 5-year PFS rates of the patients in the same categories were 67.7±8.5% and 81.6±7.5%, respectively (P=0.401). The 5-year OS and PFS rates according to the IPI, aaIPI, R-IPI, and NCCN-IPI did not show statistically significant differences between the subgroups (P>0.05) when the subjects were stratified by each prognostic risk model.

High-dose chemotherapy with auto-SCT has been performed for curative purposes and is now the treatment of choice in patients with relapsed, chemotherapy-sensitive DLBCL. In addition, auto-SCT has been applied in patients with high risk aggressive NHL to improve the outcome of consolidative treatment. Recent randomized studies showed no significant survival benefit to upfront auto-SCT compared with rituximab-containing chemoimmunotherapy alone for aggressive B-cell lymphoma [678]. However, a prospective randomized trial performed by Vitolo et al. demonstrated that the 3-year PFS was significantly higher in the upfront auto-SCT group compared with the non-auto-SCT group in patients with high risk DLBCL [9]. The role of upfront auto-SCT remains to be established with long-term follow-up in patients with high risk DLBCL.

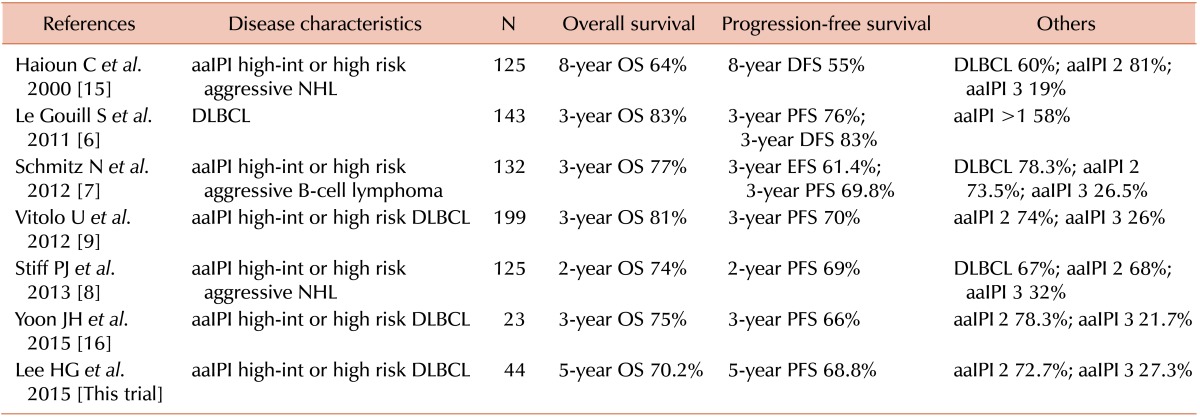

The IPI and aaIPI were developed to predict long-term survival for aggressive NHL, including DLBCL, before the introduction of rituximab to the medical field [1]. The IPI was also useful in predicting the outcome in patients with aggressive CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP [10]. The IPI or aaIPI at diagnosis was found to be of value in predicting the OS and PFS in 25 patients with DLBCL who were treated with R-CHOP followed by upfront auto-SCT [11]. The 5-year OS and PFS of the high risk group were lower than those of the high intermediate risk group (P=0.04 and P=0.092, respectively). When the aaIPI was applied to 242 patients with relapsed CD20-positive DLBCL, an aaIPI score of 2 to 3 was a significant prognostic factor predicting 4-year OS and PFS after salvage auto-SCT (P<0.001) [12]. In contrast, a French prospective multicenter trial showed that 3-year PFS did not differ between the aaIPI high intermediate and high risk groups when 155 patients with DLBCL were treated with rituximab combined with ACVBP (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, and prednisolone) and upfront auto-SCT [13]. Another retrospective study showed that the 5-year OS and PFS did not significantly differ between the high intermediate and high risk groups based on the aaIPI when 22 patients with DLBCL were treated with rituximab-containing induction chemotherapy followed by upfront auto-SCT [14]. Here we summarize the representative survival data of patients with aaIPI high intermediate or high risk aggressive NHL, including DLBCL, who were treated with upfront auto-SCT (Table 5) [7891516].

Sehn et al. reported that the R-IPI identified three distinct prognostic groups with a better predictive value of 4-year OS and PFS for patients with DLBCL treated with R-CHOP compared to the standard IPI [2]. The French trial, mentioned above, also analyzed the data regarding whether the outcomes were different when the subjects were stratified according to the R-IPI risk classification [13]. There were no differences in OS and PFS between the R-IPI good and poor risk groups.

Recently, the NCCN-IPI has been proposed as a model with better discrimination of 5-year OS and PFS for patients with DLBCL treated with rituximab-containing chemotherapy as compared to the IPI for risk stratification [3]. So far, however, it has not been proved that the NCCN-IPI is a useful prognostic model for patients with DLBCL treated with rituximab-containing chemotherapy followed by upfront auto-SCT.

Because it was difficult to find an ideal prognostic model without controversy to predict outcomes for patients with DLBCL who were treated with chemoimmunotherapy followed by upfront auto-SCT, we applied 4 prognostic models to the prediction of survival in our study: the IPI, aaIPI, R-IPI, and NCCN-IPI. Unfortunately, none of the models demonstrated a statistically significant difference for OS and PFS among the risk groups when the patients were stratified by each risk classification.

In conclusion, the OS and PFS rates according to the IPI, aaIPI, R-IPI, and NCCN-IPI did not significantly differ among the subgroups. There was no ideal prognostic model among the established ones for CD20-positive DLBCL patients who were treated with R-CHOP followed by upfront auto-SCT. A new prognostic model may be necessary to identify the patients who will gain the maximum benefit from upfront auto-SCT in the rituximab era.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The clinical data for this study were collected from the Korean Blood and Marrow Transplantation Registry (KBMTR), the Korean Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

References

1. A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma The International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. N Engl J Med. 1993; 329:987–994. PMID: 8141877.

2. Sehn LH, Berry B, Chhanabhai M, et al. The revised International Prognostic Index (R-IPI) is a better predictor of outcome than the standard IPI for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Blood. 2007; 109:1857–1861. PMID: 17105812.

3. Zhou Z, Sehn LH, Rademaker AW, et al. An enhanced International Prognostic Index (NCCN-IPI) for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated in the rituximab era. Blood. 2014; 123:837–842. PMID: 24264230.

4. Lee HG, Choi Y, Kim SY, et al. R-CHOP chemoimmunotherapy followed by autologous transplantation for the treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Res. 2014; 49:107–114. PMID: 25025012.

5. Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25:579–586. PMID: 17242396.

6. Le Gouill S, Milpied NJ, Lamy T, et al. First-line rituximab (R) high-dose therapy (R-HDT) versus R-CHOP14 for young adults with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Preliminary results of the GOELAMS 075 prospective multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29(Suppl):abst 8003.

7. Schmitz N, Nickelsen M, Ziepert M, et al. Conventional chemotherapy (CHOEP-14) with rituximab or high-dose chemotherapy (MegaCHOEP) with rituximab for young, high-risk patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma: an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial (DSHNHL 2002-1). Lancet Oncol. 2012; 13:1250–1259. PMID: 23168367.

8. Stiff PJ, Unger JM, Cook JR, et al. Autologous transplantation as consolidation for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369:1681–1690. PMID: 24171516.

9. Vitolo U, Chiappella A, Brusamolino E, et al. Rituximab dose-dense chemotherapy followed by intensified high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (HDC+ASCT) significantly reduces the risk of progression compared to standard rituximab dose-dense chemotherapy as first line treatment in young patients with high-risk (aa-IPI 2-3) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): Final results of phase III randomized trial DLCL04 of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi (FIL). Blood. 2012; 120(Suppl):abst 688.

10. Ziepert M, Hasenclever D, Kuhnt E, et al. Standard International prognostic index remains a valid predictor of outcome for patients with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28:2373–2380. PMID: 20385988.

11. Inano S, Iwasaki M, Iwamoto Y, et al. Impact of high-dose chemotherapy and autologous transplantation as first-line therapy on the survival of high-risk diffuse large B cell lymphoma patients: a single-center study in Japan. Int J Hematol. 2014; 99:162–168. PMID: 24338743.

12. Gisselbrecht C, Schmitz N, Mounier N, et al. Rituximab maintenance therapy after autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients with relapsed CD20(+) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: final analysis of the collaborative trial in relapsed aggressive lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012; 30:4462–4469. PMID: 23091101.

13. Fitoussi O, Belhadj K, Mounier N, et al. Survival impact of rituximab combined with ACVBP and upfront consolidation autotransplantation in high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma for GELA. Haematologica. 2011; 96:1136–1143. PMID: 21546499.

14. Takasaki H, Hashimoto C, Fujita A, et al. Upfront autologous stem cell transplantation for untreated high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in patients up to 60 years of age. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013; 13:404–409. PMID: 23763919.

15. Haioun C, Lepage E, Gisselbrecht C, et al. Survival benefit of high-dose therapy in poor-risk aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: final analysis of the prospective LNH87-2 protocol--a groupe dEtude des lymphomes de l'Adulte study. J Clin Oncol. 2000; 18:3025–3030. PMID: 10944137.

16. Yoon JH, Kim JW, Jeon YW, et al. Role of frontline autologous stem cell transplantation in young, high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients. Korean J Intern Med. 2015; 30:362–371. PMID: 25995667.

Fig. 1

Probability of overall survival (OS) (A) and progression-free survival (PFS) (B) after autologous stem cell transplantation according to the International Prognostic Index (IPI) score at diagnosis.

Fig. 2

Probability of overall survival (OS) (A) and progression-free survival (PFS) (B) after autologous stem cell transplantation according to the age-adjusted International Prognostic Index (aaIPI) score at diagnosis.

Fig. 3

Probability of overall survival (OS) (A) and progression-free survival (PFS) (B) after autologous stem cell transplantation according to the revised International Prognostic Index (R-IPI) score at diagnosis.

Fig. 4

Probability of overall survival (OS) (A) and progression-free survival (PFS) (B) after autologous stem cell transplantation according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network International Prognostic Index (NCCN-IPI) score at diagnosis.

Table 2

The numbers and percentages of patients classified into the risk groups of each prognostic model.

Table 4

Transplantation characteristics.

Abbreviations: SCT, stem cell transplantation; G-CSF, granulocytecolony stimulating factor; BU, busulfan; CY, cyclophosphamide; VP-16, etoposide; MEL, melphalan; MITO, mitoxantrone; ARA-C, cytosine arabinoside; BCNU, carmustine; IFOS, ifosfamide; CARB, carboplatin; CD, cluster of differentiation; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; PLT, platelet.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download