Abstract

Background

The eosin-5'-maleimide (EMA) binding test using flow cytometry is a common method to measure reduced mean channel fluorescence (MCF) of EMA-labeled red blood cells (RBCs) from patients with red cell membrane disorders. The basic principle of the EMA-RBC binding test involves the covalent binding of EMA to lysine-430 on the first extracellular loop of band 3 protein.

Methods

In the present study, the MCF of EMA was analyzed for samples derived from 12 healthy volunteers (controls) to determine the stability (i.e., the percentage decrease in fluorescence) of EMA over a period of 1 year.

Go to :

Eosin-5'-maleimide (EMA) is a fluorescent dye that is used to detect red cell membrane defects by flow cytometry. It is primarily utilized to diagnose hereditary spherocytosis (HS), which may be transfusion-dependent. In addition, reports have indicated the applicability of EMA to hemolytic disorders such as cryohydrocytosis (a type of hereditary stomatocytosis), Southeast Asian ovalocytosis, and congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II [1]. Studies have also illustrated the use of EMA in the differential diagnosis of HS and hereditary pyropoikilocytosis [2]. The diagnosis of patient susceptibility to hemolytic disorders depends on qualitative parameters such as clinical presentation, family history, peripheral smear profile, and red blood cell (RBC) indices [3].

The RBC membrane is a lipid bilayer consisting of specific protein components such as α and β-spectrin, ankyrin, band 3, protein 4.1, protein 4.2, and actin. These proteins maintain the structural integrity of the RBC membrane and defects in the genes encoding these proteins decrease cell membrane integrity [4]. Red cell membrane disorders are also detected using osmotic fragility (OF) tests, including the NaCl-induced OF test (which measures the resistance of red cells to lysis after spiking the cell sample in NaCl solutions with different concentrations), glycerol lysis test (GLT), acidified GLT, and pink test [5]. The principle of the EMA-RBC binding test is based on the fact that EMA binds covalently with lysine-430 on the first extracellular loop of band 3 protein [6]. Inadequate expression of band 3 protein will result in reduced binding of EMA [67].

Patients with HS show reduced mean channel fluorescence (MCF) of EMA based on flow cytometry and reduced mean cell volume (MCV). Hunt et al. [1] described the normalization of EMA-RBC fluorescence data and determined that a cut-off ratio of 0.8 can be used to differentiate normal controls from HS patients. This ratio was calculated as the test MCF normalized by the mean of 6 normal control MCFs. Relative to other tests, the EMA binding test shows the greatest specificity and sensitivity (99.1% and 92.1%, respectively) for HS detection [89].

The aim of our study was to determine the fluorescence activity of EMA dye during flow cytometry in normal individuals over a period of one year. A total of 12 healthy volunteers were studied as controls.

Go to :

In the prospective study, a total of 12 healthy, regular donors were selected and studied over a period of 12 months. Informed consent from all the volunteers and ethical approval was also obtained. Peripheral blood samples from the donors were collected in EDTA vacutainers and processed within 2 hours. None of the donors was sensitized. The EMA binding test was performed as described elsewhere [6]. A total of 7 runs were performed on a single sample. The test was performed at a frequency of once every 2 months, and all donors were assessed on the same day.

The red cell indices of the donors were obtained every time the test was performed. These parameters were determined using a Sysmex automated cell counter (Sysmex K-1100, Kobe, Japan).

In this prospective study, a FACSCalibur flow cytometer was used (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). The cytometer was calibrated using BD Calibrite Beads (Becton Dickinson) every time the flow cytometer was switched on. EMA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) dye solutions were stored in aliquots at -80℃ over a period of 12 months.

Briefly, 25 µL of working EMA dye solution was mixed with 5 µL of washed donor RBCs in a flow tube. The tube was incubated for one hour at room temperature in dark conditions. After incubation, the EMA-RBC flow tube was washed twice with 2 mL of sheath fluid (Becton Dickinson) at 3,000 rpm for 5 min. This sheath fluid mainly consisted of phosphate-buffered saline, with certain additives. The pellet was obtained after washing and was resuspended in 300 µL of sheath fluid in the flow tube; a total of 100,000 events were acquired in the FL1 channel. The MCF reading for each donor was recorded. The cytometer was kept in a temperature-controlled room and daily routine start up, calibration, and shut down protocols were performed as per the manufacturer's recommendation.

All statistical computations were implemented in SPSS software version 18.0. Paired t-tests were used to compare the MCF values between consecutive runs.

Go to :

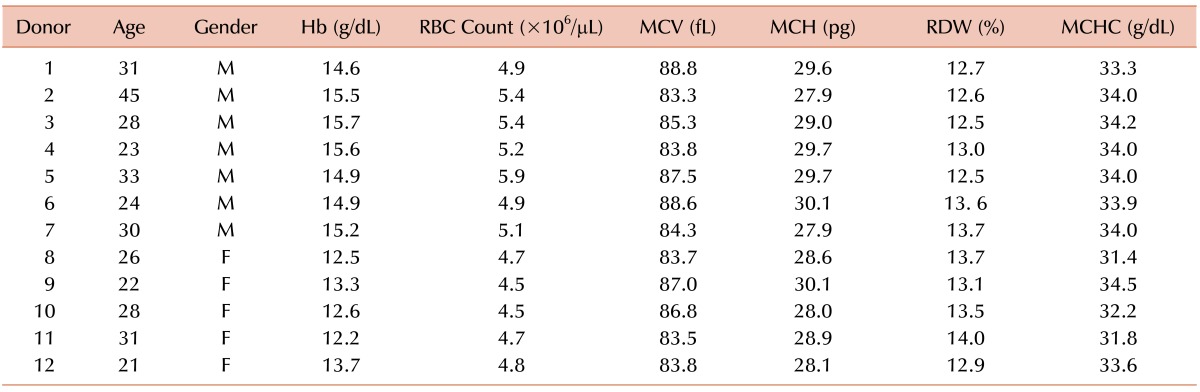

Table 1 shows all parameters for the 12 donors, such as MCV, hemoglobin, and red cell count. All parameters are presented as the means of the values obtained for all runs. The values obtained for all the donors were within normal ranges.

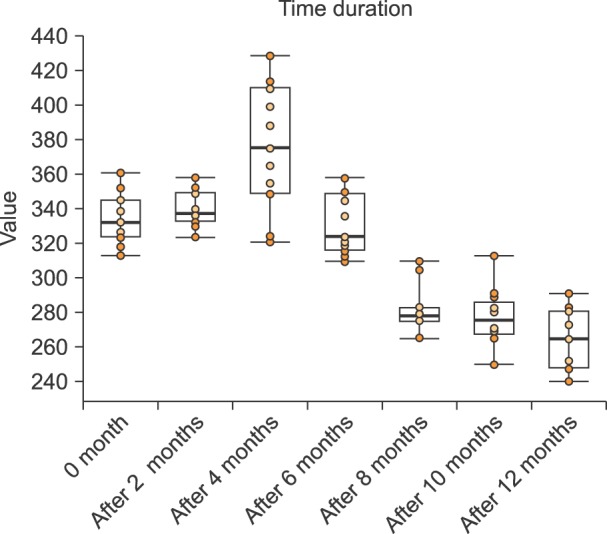

In the present study, 12 individuals were studied; 7 were males and 5 were females. Fig. 1 shows a box plot of the MCF values for the various samples over a 12-month period, assessed at 2-month intervals. As shown in Fig. 1, the mean MCF was initially 333.6, and was 339.2, 374.5, 329.3, 281.7, 277.3, and 265.2 after 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 months, respectively.

Comparisons of MCF between the initial reading and subsequent time periods were assessed by paired t-tests and the mean differences (compared to the starting value) were +5.6 (t=1.34) after 2 months, +40.9 (t=4.20) after 4 months, -4.3 (t=-0.92) after 6 months, -51.9 (t=-15.15) after 8 months, -56.3 (t=-15.30) after 10 months, and -68.4 (t=-13.40) after 12 months. Comparisons of MCF readings of sequential runs were also examined and reductions in fluorescence were calculated in terms of percentages. There was a 1% reduction in fluorescence from 0 to 2 months, and this reduction increased by 10% from 2 to 4 months and by an additional 12% from 4 to 6 months. It then decreased by 14% from 6 to 8 months, 1% from 8 to 10 months, and 4% from 10 to 12 months. The P-value was greater than 0.05 for up to 6 months, and less than 0.05 at 8 months and beyond when compared to the baseline value. These data clearly show that there was a significant decrease in MCF after 6 months; however, no significant decrease was observed up to 6 months.

Go to :

The EMA binding test using flow cytometry is a rapid, sensitive, and reliable diagnostic aid [6]. Conventional diagnosis of hereditary RBC membrane disorders is labor-intensive, time-consuming, and has low sensitivity and specificity [10]. In contrast, the EMA test can be performed in less than 2 hours. Previous results have illustrated its high specificity (99.1%) and sensitivity (92.1%), indicating is it a useful diagnostic tool for red cell membrane disorders [8]. This method can be used to detect not only band 3 deficiencies, but also spectrin and protein 4.2 deficiencies [6].

Our study showed minimal changes in the MCF over a 6-month period for EMA. However, the stability of the EMA dye decreased continuously after 6 months, with a significant decrease relative to baseline levels at 8 months. Dye stability, dye concentration, incubation time, storage conditions of blood samples, and delay in flow cytometric analysis of EMA-labeled red cells each play a crucial role in the reproducibility of results. Reports on dye storage conditions have indicated that EMA dye stored at -20℃ remains stable over a period of 4 months, but storage at 4℃ for 1 week results in a rapid decrease in labeling efficiency [6]. However, in this study, the dye was stored at -80℃ over a period of 1 year. Previous studies have also illustrated that EMA binding test results are not influenced by shipping or storage for up to 6 days [8].

EMA is light-sensitive and is hydrolyzed in aqueous buffer. It is recommended that red cells are incubated in the dark for 1 hour at room temperature with intermittent mixing [3]. Although the EMA binding test provides quantitative results that aid in positive and negative discrimination of test results, EMA dye is relatively unstable as a working solution. In a study by Kedar et al., [7] the fluorescence intensity of the working solution remained stable for 4 months when stored at -80℃. However, our results indicate that it remains stable for a period of 6 months. There is a significant decrease in MCF beyond this period of time, after which the same dye should not be used.

In summary, the EMA binding test is a rapid, sensitive, specific, and reliable test for HS. However, despite the specificity of EMA for HS detection, it is important to consider a patient's clinical history, family history, etc. The results of the present study demonstrate high dye stability for up to 6 months, during which the dye can be optimally utilized. We recommend reconstitution of the dye for the test every 6 months and storage at -80℃ in dark conditions.

Go to :

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Mr. Manish Singh, Dr. Padam Singh, and Mr. Akhil Kumar Gawar for helping with the statistical analysis.

Go to :

Notes

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Go to :

References

1. Hunt L, Greenwood D, Heimpel H, Noel N, Whiteway A, King MJ. Toward the harmonization of result presentation for the eosin-5'-maleimide binding test in the diagnosis of hereditary spherocytosis. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2015; 88:50–57. PMID: 25227211.

2. King MJ, Telfer P, MacKinnon H, et al. Using the eosin-5-maleimide binding test in the differential diagnosis of hereditary spherocytosis and hereditary pyropoikilocytosis. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2008; 74:244–250. PMID: 18454487.

3. Bolton-Maggs PH, Stevens RF, Dodd NJ, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of hereditary spherocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2004; 126:455–474. PMID: 15287938.

4. An X, Mohandas N. Disorders of red cell membrane. Br J Haematol. 2008; 141:367–375. PMID: 18341630.

5. Bianchi P, Fermo E, Vercellati C, et al. Diagnostic power of laboratory tests for hereditary spherocytosis: a comparison study in 150 patients grouped according to molecular and clinical characteristics. Haematologica. 2012; 97:516–523. PMID: 22058213.

6. King MJ, Behrens J, Rogers C, Flynn C, Greenwood D, Chambers K. Rapid flow cytometric test for the diagnosis of membrane cytoskeleton-associated haemolytic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2000; 111:924–933. PMID: 11122157.

7. Kedar PS, Colah RB, Kulkarni S, Ghosh K, Mohanty D. Experience with eosin-5'-maleimide as a diagnostic tool for red cell membrane cytoskeleton disorders. Clin Lab Haematol. 2003; 25:373–376. PMID: 14641141.

8. Girodon F, Garçon L, Bergoin E, et al. Usefulness of the eosin-5'-maleimide cytometric method as a first-line screening test for the diagnosis of hereditary spherocytosis: comparison with ektacytometry and protein electrophoresis. Br J Haematol. 2008; 140:468–470. PMID: 18162119.

9. Park SH, Park CJ, Lee BR, et al. Comparison study of the eosin-5'-maleimide binding test, flow cytometric osmotic fragility test, and cryohemolysis test in the diagnosis of hereditary spherocytosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014; 142:474–484. PMID: 25239414.

10. Korones D, Pearson HA. Normal erythrocyte osmotic fragility in hereditary spherocytosis. J Pediatr. 1989; 114:264–266. PMID: 2915286.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download