Abstract

Background

Although apoptosis occurs in nucleated cells, studies show that this event also occurs in some anucleated cells such as platelets. During storage of platelets, the viability of platelets decreased, storage lesions were observed, and cells underwent apoptosis. We investigated the effects of caspase-3 inhibitor on the survival and function of platelets after different periods of storage.

Methods

Platelet concentrates were obtained from the Iranian Blood Transfusion Organization in plastic blood bags. Caspase-3 inhibitor (Z-DEVD-FMK) was added to the bags. These bags along with control bags to which no inhibitor was added were stored in a shaking incubator at 22℃ for 7 days. The effects of Z-DEVD-FMK on the functionality of platelets were analyzed by assessing their ability to bind to von Willebrand factor (vWF) and to aggregate in the presence of arachidonic acid and ristocetin. Cell survival was surveyed by MTT assay.

Results

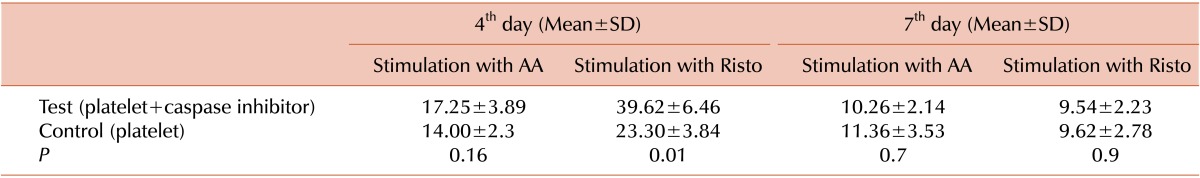

At day 4 of storage, ristocetin-induced platelet aggregation was significantly higher in the inhibitor-treated (test) than in control samples; the difference was not significant at day 7. There was no significant difference in arachidonic acid-induced platelet aggregation between test and control samples. However, at day 7 of storage, the binding of platelets to vWF was significantly higher in test than in control samples. The MTT assay revealed significantly higher viability in test than in control samples at both days of study.

Platelets are enucleated cells derived from bone marrow megakaryocytes. They play a very important role in hemostasis, blood clotting, repair and thrombosis [1, 2]. Platelet concentrates (PCs) are most frequently transfused to thrombocytopenic recipients to maintain primary hemostasis or to patients whose platelets are not fully functional, either because of a specific platelet disorder or, in some patients, after taking medication such as acetylsalicylic acid [2, 3].

During storage, the metabolic activity of platelets and residual leukocytes continues to consume nutrients and produce harmful metabolic products. Activated clotting factors, cellular debris, and proteolytic enzymes found in the suspending plasma can adversely affect platelets. These structural changes to the platelet cytoskeleton and surface membrane antigens that occur during storage also appear related to poorer in vivo post transfusion recovery and survival [4, 5]. One of the important platelet storage lesion (PSL) in PCs is apoptosis. Apoptosis is a major form of cell death, characterized by a series of apoptosis-specific morphological alterations and nucleosomal DNA fragmentation of genomic DNA [5, 6]. Recent studies toward understanding of the apoptosis machinery have revealed the essential roles of a family of cysteine aspartyl proteases named caspases. They are normally expressed as proenzymes that mature to their fully functional form through proteolytic cleavage [6, 7, 8]. Caspase-3 is a well-known representative of this subfamily. The cellular substrates of active caspase-3 range widely from nuclear proteins, such as enzymatic regulators for DNA repair, to cytoplasmic proteins, such as gelsolin, a cytoskeletal regulatory protein. Although the nucleus is an important apoptotic target, the role of the nucleus in this programmed process is unclear. Activated caspases cleave a critical set of cellular proteins selectively and in a coordinated manner leading to cell death [9].

The role of apoptosis in PSL is poorly understood [10, 11, 12, 13]. It is still a matter of conjecture that whether the enucleated platelets can undergo apoptosis, which is a genetically programmed method. However, certain experimental evidence likes the expression of phosphatidyl serine (PS) on the platelet membrane, which is typical of nucleated cells, points to the fact that apoptotic machinery might be present in the platelets. The doubt remains whether platelet retains the memory of "parental" megakaryocytes for apoptosis or whether platelet mitochondrial DNA has a major role in both the apoptotic process and the PSL [12].

For platelets to maintain their in vitro quality and in vivo effectiveness, they need to be stored at room temperature with gentle agitation in gas-permeable containers [14]. Nevertheless, in vitro, deleterious changes in structure and function (PSL) have restricted the platelet shelf-life to 5 days.

In this study, the caspase-3 inhibitor was employed to overcome the apoptosis effects in PCs during storage. Affecting the caspase inhibitor in the function and survival of PCs could imply a role for apoptosis in PSL.

The lyophilized caspase-3 inhibitor was dissolved in DMSO (10 mM stock), divided into small aliquots, and kept at -20℃.

Fifteen single donor PCs bags (JMS Singapore Pte Ltd. contained CPDA-1 solution) were prepared from IBTO (24 hours after PCs preparation and completion of viral safety tests). Informed consent was obtained from the blood candidates by Iranian Blood Transfusion Organization (IBTO). Platelet rich plasma (PRP) was used to prepare PCs. Each unit of PCs was divided into two bags using connecting device instrument. In one of the bags, the caspase-3 inhibitor (Z-DEVD-FMK, BioVision Research Products, USA) was introduced. For aseptic infusion of caspase 3 inhibitor into bags, one aliquot of the inhibitor was diluted in small volume of sterile saline and injected using insulin syringe under class II laminar flow (final concentration 16 µM). The concentration of 16 µM was chosen based on the preliminary studies (data not shown). Sampling of platelets (5 mL) was accomplished at the days 4 and 7 of storage.

Cell viability was analyzed using a colorimetric assay; methyl-thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) based (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Platelets were counted using an automated hematology analyzer (Sysmex K-1000, Kobe, Japan) and 300,000 cells/µL were introduced in a microplate in a final volume of 100 µL per well. 10 µL of MTT labeling reagent (0.5 mg/mL) was added to each well. The microplate was incubated for 4 h in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO2). Then 100 µL of the solubilization solution was added into each well and stand overnight in the incubator. The spectrophotometrical absorbance of the wells was measured at 570 nm. In this method, cell viability directly correlated to the amount of purple formazan crystals formed as monitored by the absorbance (optical density, OD).

Platelet aggregations were measured with Packs-4 turbidometric aggregometer (Helena Laboratories, Beaumont, TX, USA). Platelets were stimulated with arachidonic acid (Helena BioSciences Europe, UK) 0.5 mg/mL and ristocetin (Helena BioSciences Europe, UK) 1.5 mg/mL. Aggregation was monitored by measuring an increase in light transmission on the Helena-Packs-4 analyzer.

For studying the vWF binding properties of platelets, 100 µL of platelets (105 cells) was introduced to the tubes containing 2 µL of 200 µg/mL concentration of purified human vWF (Biopur, Bubendorf, Switzerland) in the presence of 50 µg of ristocetin (Helena Laboratories, Beaumont, TX, USA) as a modulator. After 45 min of incubation at room temperature, platelets were washed and incubated for 30 min with rabbit anti-human vWF (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Platelets were washed again and incubated for 30 min with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO, USA). To ensure the specificity of the results, nonspecific antibody background binding was determined with the appropriately labeled isotypic control immunoglobulin IgG. Additionally, for each tube, another control was also utilized, which contained all reactants except the specific antibody (rabbit anti-human vWF antibody). Finally, the results of the experiment were surveyed by flow cytometry technique (Partec-pasIII, Germany).

OD 570 nm values for PCs was determined during storage of PCs (N=15) by MTT assay. MTT assay revealed that the viability of platelets was significantly decreased after 4 days of storage and was further decreased after 7 days of storage in both inhibitor-treated and control samples. At day 4 of storage, results showed the binding percent of 2.44±0.61 for test (platelet+caspase inhibitor) and 1.85±0.70 for control (platelet); the difference was significant (P=0.001). At day 7 of storage, these results were 1.61±0.8 and 1.09±0.56 for the test and control, respectively; the difference was significant (P=0.05). Therefore, at the 4th and 7th day of storage, the OD was significantly higher in the test than in the control samples. So caspase-3 inhibition can positively affect on the shelf-life of platelets.

It was of note that the differences in viability on day 7 and on day 4 of storage were significant (P=0.019 and 0.001 for the test and control samples, respectively).

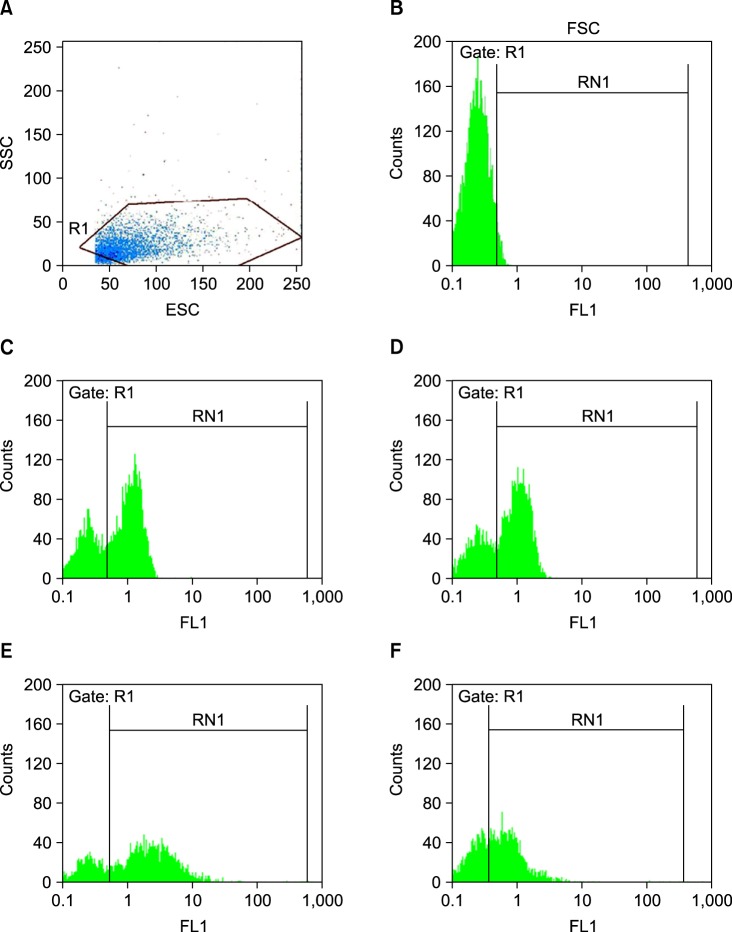

Binding of PCs (N=15) to vWF was measured by flow cytometry at days 4 and 7 of storage. At day 4 of storage, results showed the binding percent of 67.2±0.8 for test (platelet+caspase inhibitor) and 63.17±1.8 for control (platelet); the difference was not significant (P=0.08). At day 7 of storage, these results were 66±2.2 and 60.5±2.3 for the test and control, respectively; the difference was significant (P=0.01).

This study demonstrated the ability of platelets to bind to vWF in vitro. The ability of platelets in PCs to bind to vWF decreased during 7 days storage at 22℃ (Fig. 1). Besides, binding of platelets to vWF was higher in inhibitor-treated samples than in control samples during storage. However, the difference was only significant after 7 days of storage (P=0.01).

At the 4th day of storage, the ristocetin-induced platelet aggregation was significantly higher in the test (inhibitor-treated) than in the control samples, whereas the difference was not significant at the 7th day. Additionally, the arachidonic acid-induced platelet aggregation was moderately higher in the test than in the control samples at the 4th day of storage (Table 1).

Over the last decade, it has been found that the nucleus itself is not required for apoptosis, as apoptotic stimuli can induce typical apoptotic morphologic and biochemical changes in platelets [15], providing support to the concept of extranuclear apoptotic cytoplasmic machinery that does not require nuclear participation.

In this study, we introduced caspase-3 inhibitor in the final concentration of 16 µM into PCs and surveyed their aggregation potential, endurance, and vWF binding virtues during storage. The ristocetin-induced platelet aggregation was significantly higher in the test (inhibitor-treated) than in the control samples at the 4th day of storage. Besides, the binding of platelets to vWF was significantly higher at both days of study in the test than in the control samples; but the difference was significant at the 7th day of storage. MTT showed significantly higher survival levels in the test than in the control samples at both days of study.

There were very limited researches related to caspase inhibition in platelets. Piguet and Vesin [16] used a rabbit anti-platelet antibody in mice. They observed that it induced a profound thrombocytopenia and activation of platelet caspases. Consequently, thrombocytopenia was prevented by the injection of a caspase inhibitor ZVAD-fmk. These observations indicated the activation of caspases-regulated platelet life-span. The improving effects of caspase inhibitor for platelets life-span in that study were correlated with ours, although it was carried out in vivo.

In the experiment by Cohen et al. [17], a sample of the PRP was obtained from rat blood and incubated with the pan-caspase inhibitor; z-Val-Ala-DL-Asp-fluoromethylketone (zVAD-fmk), at a concentration of 20 µM for 45 min at room temperature. Forty-five minutes was chosen as the incubation time. They showed that caspase inhibition decreased both platelet phosphatidylserine exposure and aggregation. Their results indicated that caspases play a role in platelet activation. Unlike their results, we found an increasing level in the aggregation potential of platelets on treatment of PCs with caspase-3 inhibitor (Z-DEVD-FMK). They utilized the inhibitor into freshly prepared rat platelet samples and followed the results only after 45 minutes of treatment, whereas our experiment was accomplished in the PCs (blood bags) and after injection for 7 days. Other difference may be related to the difference between the human and rat source of the samples.

Another studied factor was vWF that was a multimeric plasma glycoprotein that supports platelet adhesion at sites of vascular injury. There were numerous studies related to the binding of platelets to vWF [18, 19, 20]. We didn't find any reports on vWF binding potential of platelets in the cases that caspase inhibitor had been used.

Surviving cells have been measured in vitro by several methods, e.g. counting cells that exclude trypan blue and colorimetric assay based on tetrazolium salt, MTT salt to estimate the surviving numbers of stored platelets. Vanhée used MTT to evaluate the immune reactivity of blood platelets [21]. Maekawa measured the survival levels using metabolic redox activity of platelets by MTT [22]. We also used MTT method to estimate the surviving numbers of stored platelets. But we didn't find any report for the usage of MTT for survival studies in the cases utilizing caspase inhibitors.

The presence of very limited numbers of white blood cells in PC did not interfere the results because of the presence of a control for every test sample (both of the test and control samples were originated from the same bag). Alternatively, the evaluation was not carried out on day 0 because the effects of active caspase-3 were not detectable at that time [23].

It seemed that usage of caspase-3 inhibitor could be effective for obtaining better results for the survival and function of PCs during storage. Further studies must be carried out to evaluate the effects of the inhibitors and their effectiveness to overcome the apoptosis during the storage of PCs.

Notes

This study was supported by a grant from Iranian Blood Transfusion Organization, Research Center.

This study was the result of a thesis financially supported by Blood Transfusion Research Center, High Institute for Research and Education in Transfusion Medicine, Iranian Blood Transfusion Organization, Tehran.

References

1. Stellos K, Kopf S, Paul A, et al. Platelets in regeneration. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2010; 36:175–184. PMID: 20414833.

2. Spiess BD. Platelet transfusions: the science behind safety, risks and appropriate applications. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2010; 24:65–83. PMID: 20402171.

3. White GC 2nd. Congenital and acquired platelet disorders: current dilemmas and treatment strategies. Semin Hematol. 2006; 43(1):Suppl 1. S37–S41. PMID: 16427384.

4. Thon JN, Schubert P, Devine DV. Platelet storage lesion: a new understanding from a proteomic perspective. Transfus Med Rev. 2008; 22:268–279. PMID: 18848154.

5. Shrivastava M. The platelet storage lesion. Transfus Apher Sci. 2009; 41:105–113. PMID: 19683964.

6. Salvesen GS, Dixit VM. Caspases: intracellular signaling by proteolysis. Cell. 1997; 91:443–446. PMID: 9390553.

7. Kothakota S, Azuma T, Reinhard C, et al. Caspase-3-generated fragment of gelsolin: effector of morphological change in apoptosis. Science. 1997; 278:294–298. PMID: 9323209.

8. Weil M, Jacobson MD, Raff MC. Are caspases involved in the death of cells with a transcriptionally inactive nucleus? Sperm and chicken erythrocytes. J Cell Sci. 1998; 111:2707–2715. PMID: 9718364.

9. Li J, Xia Y, Bertino AM, Coburn JP, Kuter DJ. The mechanism of apoptosis in human platelets during storage. Transfusion. 2000; 40:1320–1329. PMID: 11099659.

10. Ohto H, Nollet KE. Overview on platelet preservation: better controls over storage lesion. Transfus Apher Sci. 2011; 44:321–325. PMID: 21507724.

11. Jackson SP, Schoenwaelder SM. Procoagulant platelets: are they necrotic? Blood. 2010; 116:2011–2018. PMID: 20538794.

12. Seghatchian J, Krailadsiri P. Platelet storage lesion and apoptosis: are they related? Transfus Apher Sci. 2001; 24:103–105. PMID: 11515605.

13. Seghatchiana J, de Sousa G. Blood cell apoptosis/necrosis: some clinical and laboratory aspects. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003; 1010:540–547. PMID: 15033787.

14. van der Meer PF, de Korte D. Platelet preservation: agitation and containers. Transfus Apher Sci. 2011; 44:297–304. PMID: 21514232.

15. Kuter DJ. Apoptosis in platelets during ex vivo storage. Vox Sang. 2002; 83(Suppl 1):311–313. PMID: 12617160.

16. Piguet PF, Vesin C. Modulation of platelet caspases and life-span by anti-platelet antibodies in mice. Eur J Haematol. 2002; 68:253–261. PMID: 12144531.

17. Cohen Z, Wilson J, Ritter L, McDonagh P. Caspase inhibition decreases both platelet phosphatidylserine exposure and aggregation: caspase inhibition of platelets. Thromb Res. 2004; 113:387–393. PMID: 15226093.

18. Doggett TA, Girdhar G, Lawshe A, et al. Selectin-like kinetics and biomechanics promote rapid platelet adhesion in flow: the GPIb(alpha)-vWF tether bond. Biophys J. 2002; 83:194–205. PMID: 12080112.

19. Kang M, Wilson L, Kermode JC. Evidence from limited proteolysis of a ristocetin-induced conformational change in human von Willebrand factor that promotes its binding to platelet glycoprotein Ib-IX-V. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2008; 40:433–443. PMID: 17977030.

20. Mody NA, King MR. Platelet adhesive dynamics. Part II: high shear-induced transient aggregation via GPIbalpha-vWF-GPIbalpha bridging. Biophys J. 2008; 95:2556–2574. PMID: 18515386.

21. Vanhee D, Joseph M, Vorng H, Tonnel AB. A colorimetric assay to evaluate the immune reactivity of blood platelets based on the reduction of a tetrazolium salt. J Immunol Methods. 1993; 159:253–259. PMID: 8445256.

22. Maekawa Y, Yagi K, Nonomura A, et al. A tetrazolium-based colorimetric assay for metabolic activity of stored blood platelets. Thromb Res. 2003; 109:307–314. PMID: 12818255.

23. Li J, Xia Y, Bertino AM, Coburn JP, Kuter DJ. The mechanism of apoptosis in human platelets during storage. Transfusion. 2000; 40:1320–1329. PMID: 11099659.

Fig. 1

Flow cytometry plot. The vWF binding capacity of platelets at the days 4 and 7 of storage. (A) The platelets were gated, (B) the binding levels in the negative control in the absence of antibodies to vWF, (C) the vWF binding levels of platelets in the presence of caspase-3 inhibitor at the day 4 of storage, (D) the vWF binding levels of platelets without caspase-3 inhibitor at the day 4 of storage, and (E) the vWF binding levels of platelets in the presence of caspase-3 inhibitor at the day 7 of storage, (F) the vWF binding levels of platelets without caspase-3 inhibitor at the day 7 of storage.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download