Abstract

Background

Abbreviated chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy or full cycles of chemotherapy is recommended as a standard treatment for limited-stage (LS) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). After complete resection of tumors, however, Burkitt and childhood B-cell Non-Hodgkin lymphoma show favorable outcomes, even after abbreviated chemotherapy of only 2 or 3 cycles. We investigated the effectiveness of abbreviated chemotherapy in patients with LS DLBCL after complete tumor resection.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 18 patients with LS DLBCL who underwent complete tumor resection followed by either 3 or 4 cycles of chemotherapy between March 2002 and May 2010.

Results

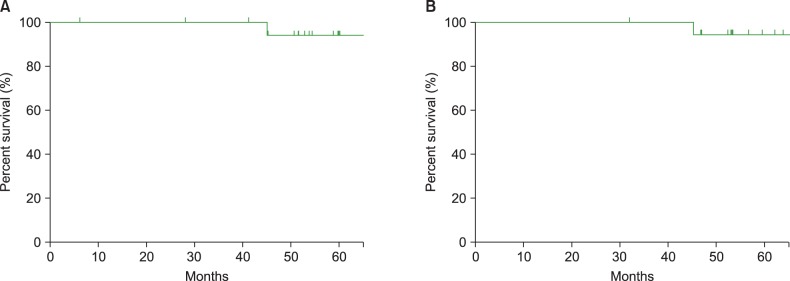

With a median follow-up period of 57.9 months (range, 31.8-130.2 months), no patients experienced disease relapse or progression; however, 1 patient experienced secondary acute myeloid leukemia during follow-up. The 5-year progression-free survival rate and overall survival rate were 93.3% and 94.1%, respectively.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common histological subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in adults [1]. Standard treatments for limited-stage (LS) DLBCL include both abbreviated systemic chemotherapy followed by involved-field radiotherapy (IFRT) and full-course chemotherapy [2].

In many cases, lesions are completely excised during the diagnostic process, especially in patients with stage I disease, as the diagnosis is best made based on histologic examination of tissues from an excisional biopsy. In addition, in the treatment of small bowel and ileocecal lymphomas with LS disease, initial surgical resection of the involved area is often performed due to the risk of obstruction or perforation of the bowel [3, 4, 5]. Although surgical resection is the most effective local therapy for the treatment of most cancers, full cycles of chemotherapy or combined treatment of chemotherapy and radiotherapy are still recommended for patients with completely resected DLBCL, similar to patients with gross tumors.

Despite being a very aggressive variant of B-cell NHL, stage I Burkitt lymphoma is treated with only 3 cycles of chemotherapy after complete surgical resection [6, 7]. In the NHL-BFM 90 study, 2 courses of chemotherapy were sufficient to treat patients with childhood B-cell neoplasms after complete resection [8].

For patients with completely resected DLBCL, the number of cycles of chemotherapy has not been questioned so far. Thus, we aimed to investigate the effectiveness of an abbreviated course of chemotherapy after complete resection in patients with LS DLBCL.

Between March 2002 and May 2010, 632 patients were diagnosed as having DLBCL in our center. Among them, 18 patients who had Ann Arbor stage I or II disease and who had initially undergone complete surgical resection of their tumors before chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy were included in this study. Diagnosis was made according to the World Health Organization criteria [9]. Patients with primary CNS lymphoma or mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, involvement of the breast or testis, positive serology for HIV, previous organ transplantation, and concomitant or previous cancers were excluded. The institutional review board of the Asan Medical Center approved this study.

A cycle of R-CHOP consisted of 375 mg/m2 rituximab, 750 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide, 50 mg/m2 doxorubicin and 1.4 mg/m2 vincristine (maximal dose of 2 mg), all on day 1. Patients also received 100 mg/day prednisolone orally on days 1.5. This cycle was repeated every 21 days. Patients diagnosed before 2003 were treated without rituximab. Primary prophylactic use of granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) was not employed. Eighteen patients with completely resected DLBCL underwent 3 or 4 cycles of R-CHOP or CHOP chemotherapy at the discretion of the attending physician as well as according to the patients' preference. No patients underwent radiotherapy.

Responses were evaluated according to the revised international workshop criteria [10]. Follow-up physical examinations, laboratory screenings, and neck, chest and abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) scans were performed every 3 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for 3 years, and annually thereafter. Since there was no evaluable lesion after surgery, patients underwent CT scans to confirm whether they had relapsed or not. If a recurrence was suspected, we conducted an additional positron emission tomography (PET) scan.

Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from diagnosis to relapse or death from any cause. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from diagnosis to death from any cause. Survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. SPSS software version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

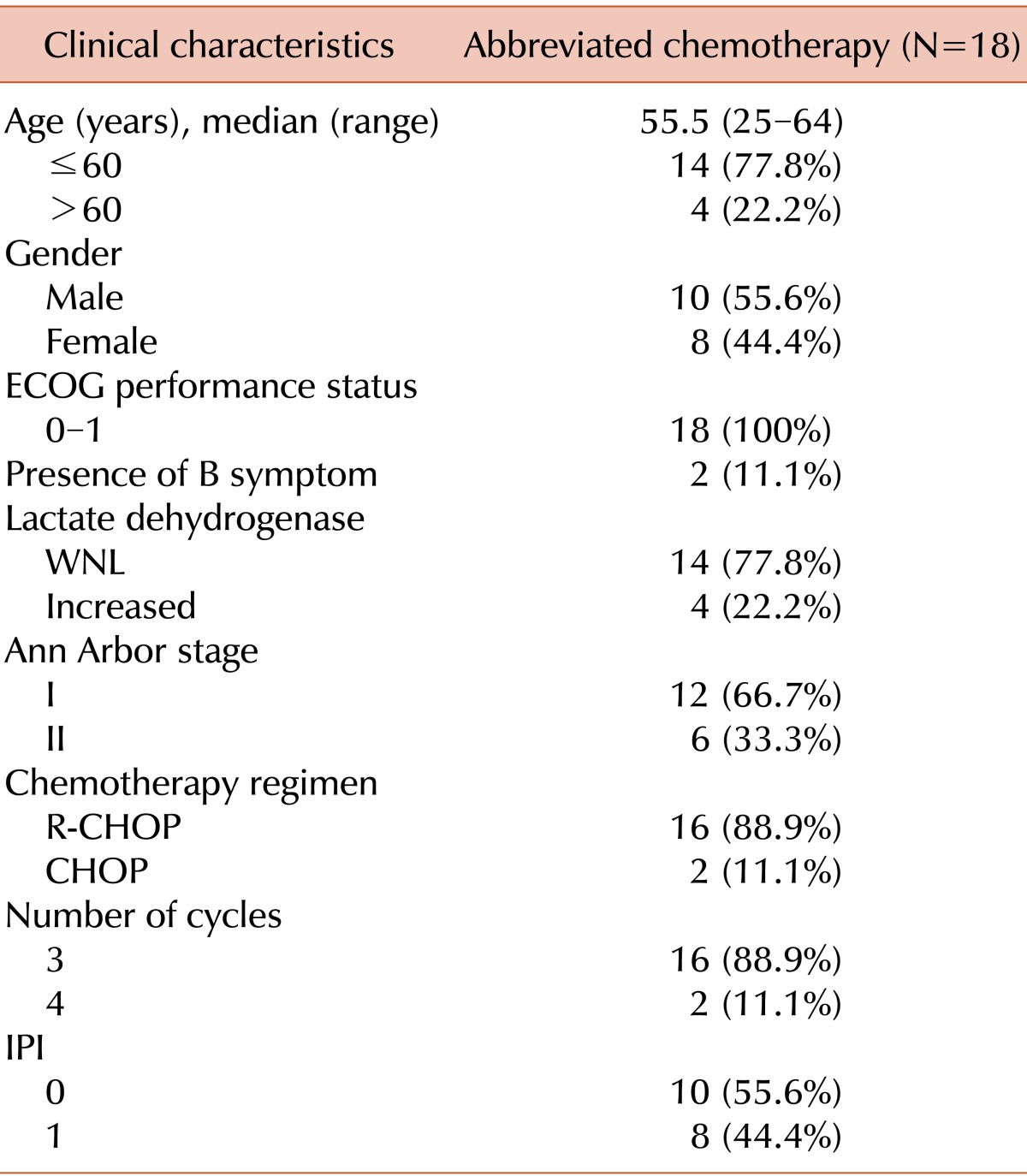

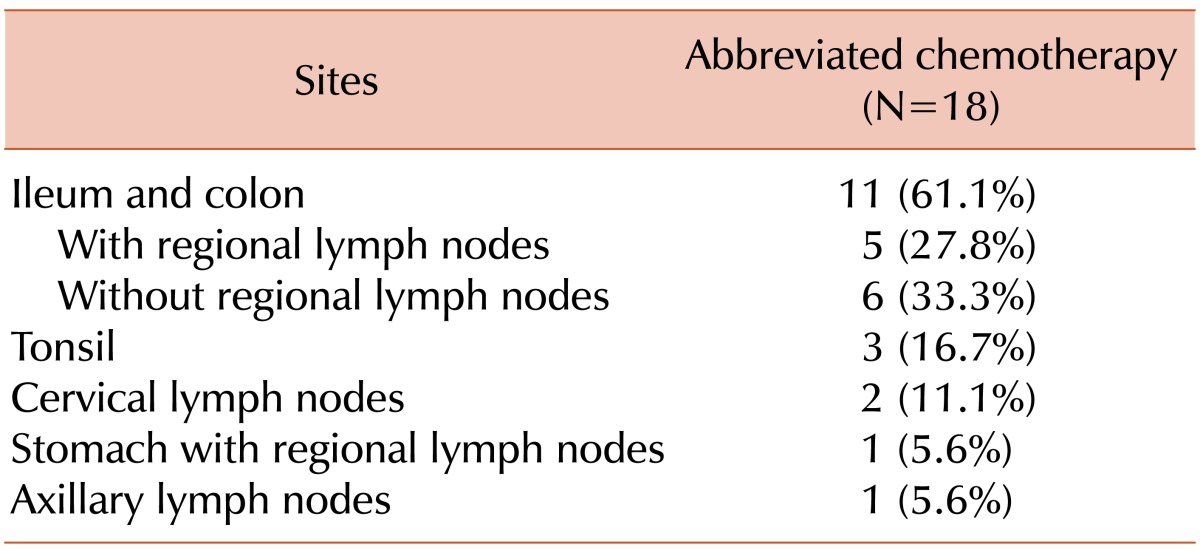

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age was 55.5 years (range, 25-64 years) at diagnosis and all patients were classified into the low-risk group according to the international prognostic index (IPI). The most commonly involved site was the ileocecum (Table 2). Out of the 18 patients, 6 (33.3%) had stage II disease. The colon or ileum was the primary disease site in 5 patients and the stomach was the primary site in the remaining patient; in this case, the patient was initially diagnosed with gastric adenocarcinoma and underwent gastrectomy. However, the diagnosis was revised to DLBCL after gastrectomy. One patient had a bulky disease in the small bowel and 2 patients had an approximately 10-cm mass at the same site. Out of 18 patients, 2 patients underwent 4 cycles of chemotherapy, and all the others had 3 cycles at the discretion of the physicians.

Three patients had tonsil lymphoma and 2 patients had lymphoma in the submandibular and cervical lymph node, respectively. The patient with lymphoma in the submandibular lymph node underwent an excisional biopsy at an outside hospital and no lesion was observed on CT or PET-CT scans after the biopsy. Another patient had a large 8-cm cervical lymphadenopathy and underwent left radical neck dissection, which was confirmed to be an R0 resection. One patient had axillary lymph node involvement and underwent axillary lymph node dissection. A 5-cm mass was found, and no residual lesion was observed in a post-operative staging workup.

The median follow-up duration was 57.9 months (range, 31.8-130.2 months). None of the patients experienced relapse or progression of lymphoma. However, 1 patient developed AML after 28 months from completion of the treatment and died of AML progression. The 5-year PFS and OS were 93.3% and 94.1%, respectively, in the cohort (Fig. 1). The median PFS and OS had not yet been reached at the time of this analysis.

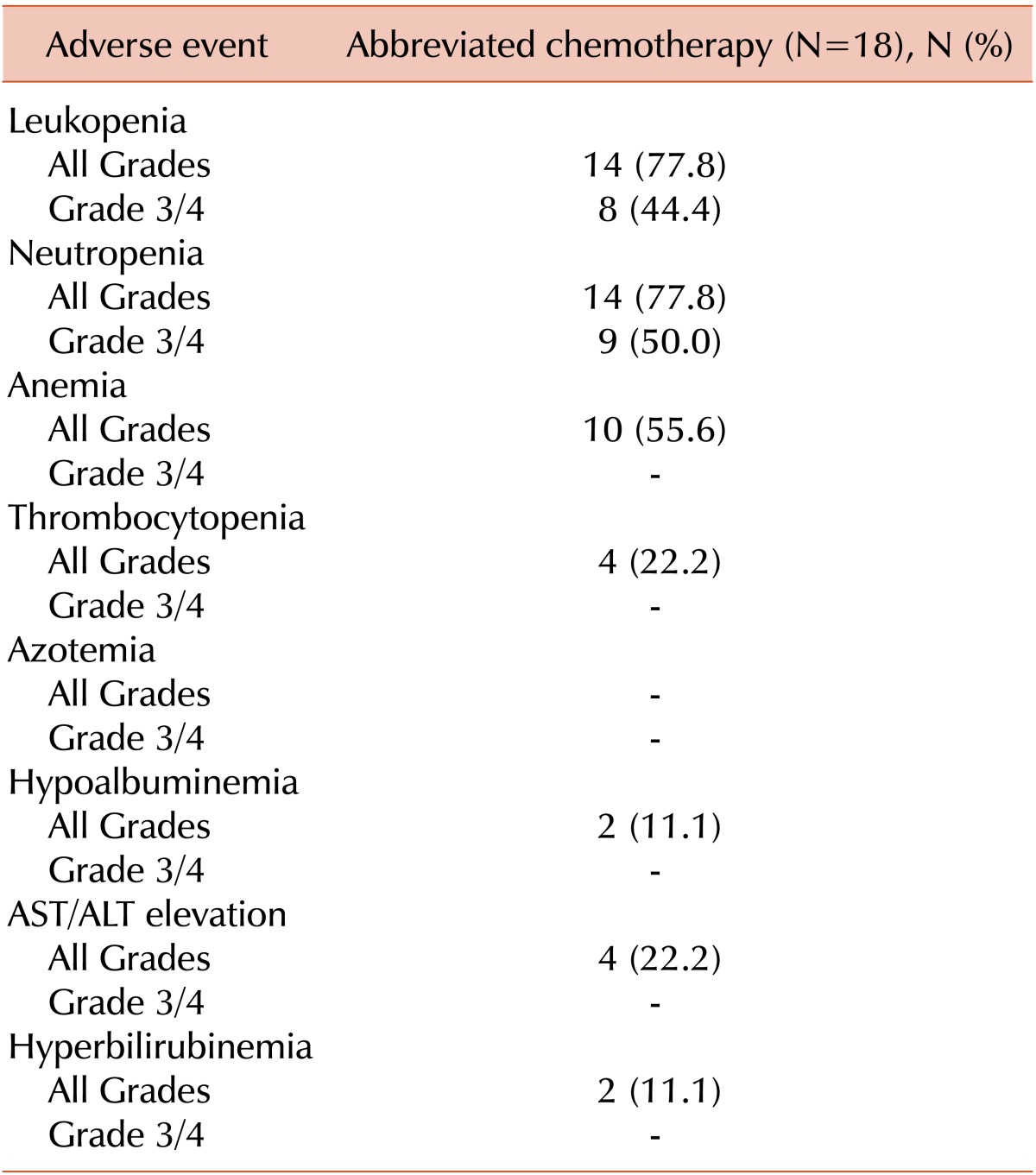

Nine patients (50.0%) suffered from grade 3 or 4 neutropenia. Of them, 1 patient experienced febrile neutropenia after the first cycle of R-CHOP. During follow-up, none of the patients experienced heart failure or grade 3/4 infections. Adverse events are summarized in Table 3.

This study sought to determine if patients without any residual tumor require the same treatment as those with gross tumors. According to the current practice guidelines, every patient with LS DLBCL should be given full cycles of chemotherapy or a few cycles of chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy, even after complete resection of their tumor.

Some aggressive lymphomas, such as Burkitt and childhood B-cell NHL, show very favorable outcomes with only 2 or 3 cycles of chemotherapy after tumor resection [6, 8]. Thus, we treated some of our patients with abbreviated cycles of chemotherapy after full discussion with the patients.

None of the patients experienced relapse or progressive disease and only 1 died of secondary AML resulting in the 5-year PFS of 93.3% and the 5-year OS of 94.1%. These outcomes are also similar to those from the prospective trials involving low-risk LS patients [11, 12]. The MabThera International Trial (MInT) included 597 young patients with stage II or bulky stage I disease [12, 13]. Patients with an age-adjusted IPI of 0 and no bulky disease treated with 6 cycles of CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab had a 3-year event-free survival (EFS) and OS of 89% and 98%, respectively and those with an IPI of 1 or a bulky mass, or both, had an EFS and OS of 76% and 91%, respectively. In the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) 0014 study, 60 patients with LS disease were treated with 4 infusions of rituximab and 3 cycles of CHOP followed by IFRT. At a median follow-up of 5.3 years, the 4-year PFS and OS were 88% and 92%, respectively [11]. In another study that analyzed the prognostic value of the original IPI in 1,063 patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era, the 3-year EFS, PFS and OS in patients with an original IPI of 0 or 1 were 81%, 87%, and 91%, respectively [14]. Our results showed similar outcomes compared with these trials including the same IPI score or stages.

There were several trials for abbreviated chemotherapy without radiotherapy in patients with LS DLBCL. In a study by Sehn et al., older patients (median age 67 years; range 31-88 years) with LS DLBCL were just treated with a total of 4 cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy if a complete metabolic response was achieved, as determined by PET analysis after 3 cycles of chemotherapy. The 2-year PFS and OS for PET-negative patients (N=49) were 93% and 97%, respectively. The GELA study for LS aggressive lymphoma in elderly patients (>60 years) compared 4 cycles of CHOP alone with 4 cycles of CHOP followed by radiotherapy [15]. In this trial, EFS and OS did not differ between the groups, and the 5-year EFS and OS of chemotherapy-alone group were 61% and 72%, respectively.

Although R-CHOP is a relatively tolerable regimen, in a phase III trial of CHOP vs. R-CHOP as treatment for DLBCL in the elderly, the median nadir of the neutrophil count after the first cycle fell to 400/mm3. In this trial, 37% of patients required treatment with G-CSF for neutropenia, and 12% of patients experienced grade 3/4 infections during treatment [16]. In the MInT trial, 37% of patients experienced grade 3/4 toxicities, including leucocytopenia (7%), even though G-CSF could be given at the treating physician's discretion for the alleviation or prophylaxis of neutropenia [12]. However, other trials that compared a brief course of R-CHOP/CHOP followed by IFRT to R-CHOP/CHOP alone showed more frequent episodes of grade 3/4 neutropenia in the prolonged chemotherapy arms [1, 2]. We infer from these results that abbreviated chemotherapy might reduce the frequency of severe toxicities.

Patients with NHL are at a higher risk for secondary malignant neoplasms (SMNs) than the general population and a combined modality of treatment was significantly associated with the risk for overall SMNs in a meta-analysis [17]. In our study, 1 patient developed AML during follow-up after treatment, even though he was given only abbreviated chemotherapy. In addition, cardiotoxicity is associated with increasing dose of doxorubicin [18, 19]. In a study of 3,941 patients treated with doxorubicin, 88 developed symptomatic heart failure during follow-up, and the incidence ranged from 0.14% in those who received <400 mg/m2, to 7% of those who received 550 mg/m2, and 18% of those beyond 700 mg/m2 [20, 21]. There is a variable sensitivity to doxorubicin among patients, with some experiencing cardiotoxicity at doses lower than 300 mg/m2 [22]. The factors that determine inter-individual variability with respect to the sensitivity to the cardiotoxic effects of anthracyclines are not well understood [23]. In the SEER study, the risk of heart failure was 47% higher among elderly patients treated with doxorubicin 6 or more times than among those not treated with chemotherapy [24]. The cumulative dose of doxorubicin would be reduced to 150-200 mg/m2 compared with 300-400 mg/m2, which might potentially reduce the risk of cardiac failure rates. In addition, abbreviated R-CHOP would be advantageous in terms of convenience as well as the cost of treatment.

This study has several limitations, stemming from its small sample size, relatively short follow-up period, and retrospective design. We are currently undertaking a prospective phase II trial to validate these data. In conclusion, the current results suggest that patients with LS DLBCL given only 3-4 cycles of chemotherapy after complete resection may have comparable efficacy outcomes to those given conventional treatment, which warrants a validation in prospective trials. These results indicate that more may not be always better.

References

1. Miller TP, Dahlberg S, Cassady JR, et al. Chemotherapy alone compared with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy for localized intermediate- and high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339:21–26. PMID: 9647875.

2. Hong J, Kim AJ, Park JS, et al. Additional rituximab-CHOP (R-CHOP) versus involved-field radiotherapy after a brief course of R-CHOP in limited, non-bulky diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a retrospective analysis. Korean J Hematol. 2010; 45:253–259. PMID: 21253427.

3. Kim SJ, Kang HJ, Kim JS, et al. Comparison of treatment strategies for patients with intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: surgical resection followed by chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone. Blood. 2011; 117:1958–1965. PMID: 21148334.

4. Koch P, del Valle F, Berdel WE, et al. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkins lymphoma: I. Anatomic and histologic distribution, clinical features, and survival data of 371 patients registered in the German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol. 2001; 19:3861–3873. PMID: 11559724.

5. Rawls RA, Vega KJ, Trotman BW. Small Bowel Lymphoma. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2003; 6:27–34. PMID: 12521569.

6. Diviné M, Casassus P, Koscielny S, et al. Burkitt lymphoma in adults: a prospective study of 72 patients treated with an adapted pediatric LMB protocol. Ann Oncol. 2005; 16:1928–1935. PMID: 16284057.

7. Mead GM, Sydes MR, Walewski J, et al. An international evaluation of CODOX-M and CODOX-M alternating with IVAC in adult Burkitt's lymphoma: results of United Kingdom Lymphoma Group LY06 study. Ann Oncol. 2002; 13:1264–1274. PMID: 12181251.

8. Reiter A, Schrappe M, Tiemann M, et al. Improved treatment results in childhood B-cell neoplasms with tailored intensification of therapy: A report of the Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster Group Trial NHL-BFM 90. Blood. 1999; 94:3294–3306. PMID: 10552938.

9. Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009; 114:937–951. PMID: 19357394.

10. Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25:579–586. PMID: 17242396.

11. Persky DO, Unger JM, Spier CM, et al. Phase II study of rituximab plus three cycles of CHOP and involved-field radiotherapy for patients with limited-stage aggressive B-cell lymphoma: Southwest Oncology Group study 0014. J Clin Oncol. 2008; 26:2258–2263. PMID: 18413640.

12. Pfreundschuh M, Trumper L, Osterborg A, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP-like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2006; 7:379–391. PMID: 16648042.

13. Pfreundschuh M, Kuhnt E, Trumper L, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without rituximab in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: 6-year results of an open-label randomised study of the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2011; 12:1013–1022. PMID: 21940214.

14. Ziepert M, Hasenclever D, Kuhnt E, et al. Standard International prognostic index remains a valid predictor of outcome for patients with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28:2373–2380. PMID: 20385988.

15. Bonnet C, Fillet G, Mounier N, et al. CHOP alone compared with CHOP plus radiotherapy for localized aggressive lymphoma in elderly patients: a study by the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25:787–792. PMID: 17228021.

16. Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:235–242. PMID: 11807147.

17. Pirani M, Marcheselli R, Marcheselli L, Bari A, Federico M, Sacchi S. Risk for second malignancies in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma survivors: a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2011; 22:1845–1858. PMID: 21310758.

18. Praga C, Beretta G, Vigo PL, et al. Adriamycin cardiotoxicity: a survey of 1273 patients. Cancer Treat Rep. 1979; 63:827–834. PMID: 455324.

19. Von Hoff DD, Layard MW, Basa P, et al. Risk factors for doxorubicin-induced congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 1979; 91:710–717. PMID: 496103.

20. Bristow MR, Mason JW, Billingham ME, Daniels JR. Dose-effect and structure-function relationships in doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J. 1981; 102:709–718. PMID: 7282516.

21. Swain SM, Whaley FS, Ewer MS. Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin: a retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer. 2003; 97:2869–2879. PMID: 12767102.

22. Shan K, Lincoff AM, Young JB. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Ann Intern Med. 1996; 125:47–58. PMID: 8644988.

23. Blanco JG, Sun CL, Landier W, et al. Anthracycline-related cardiomyopathy after childhood cancer: role of polymorphisms in carbonyl reductase genes-a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012; 30:1415–1421. PMID: 22124095.

24. Hershman DL, McBride RB, Eisenberger A, Tsai WY, Grann VR, Jacobson JS. Doxorubicin, cardiac risk factors, and cardiac toxicity in elderly patients with diffuse B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008; 26:3159–3165. PMID: 18591554.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download