INTRODUCTION

As the standard of living has improved and fortified food ingredients are widely distributed, it is difficult to identify diseases caused by nutritional deficiencies; however, some micronutrients remain insufficient, which causes various problems [

1,

2]. Iron and vitamin D are important micronutrients for normal growth and development of infants, yet they are frequently overlooked [

2].

Full-term infants receive the necessary iron through the placenta, which are sufficient for approximately 6 months after birth [

3]. Thereafter, infants are able to absorb sufficient levels of iron on their own. Iron deficiency (ID) can lead to growth and developmental delay, cognition and memory problems, impaired immune function, frequent infections, and iron deficiency anemia (IDA). Intestinal iron absorption is controlled and dependent on the body's need for iron. Since proteins such as flavoprotein and cytochrome are involved in this process, the effects of iron deficiency are diverse [

4,

5]. Iron passes through the blood-brain barrier, enters nerve cells, and is involved in neurotransmission and myelin formation [

6].

Vitamin D is primarily involved in bone metabolism. Vitamin D deficiency (VDD) may cause rickets in childhood, which primarily occurs at 3-18 months of age [

7]. It can cause musculoskeletal disorders such as osteomalacia in adolescents and adults [

8-

10]. Vitamin D requirements are fulfilled by ingestion of food or by skin exposure to ultraviolet B light for a sufficient period of time. It is then converted to 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] in the liver and circulates in the blood. Consequently, 25(OH)D is converted to its active form, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, by 1 α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) in the kidney, and it mediates its function by binding to the vitamin D receptor (VDR) in the nucleus and cytoplasm. It was recently discovered that VDR is widely expressed in osteoblasts, lymphocytes, mononuclear cells, and most organs such as the small intestine, colon, brain, heart, skin, gonads, prostate, and breast [

11]. Thus, in addition to bone metabolism, significant roles of 25(OH)D have been revealed in a variety of non-musculoskeletal disease contexts, such as infection control, suppression of immune responses in autoimmune diseases, and cancer suppression [

12,

13].

Numerous adverse effects have been observed in infants aged ≤24 months with iron and vitamin D deficiencies. Even in asymptomatic cases, these adverse effects may be problematic because infants are rapidly growing at this age. Decreased vitamin D levels during infancy might result in type 1 diabetes mellitus [

14]. The long-term consequences of concurrent deficiencies remain unknown.

Therefore, we studied the degree of vitamin D deficiency in iron-deficient and normal infants. Additionally, we investigated the association between feeding type, iron status, and vitamin D deficiency. Lastly, we sought to identify factors that may affect vitamin D deficiency.

Go to :

MATERIALS AND METHODS

One hundred two children between the ages of 3 and 24 months participated in a survey and underwent blood tests in the CHA Bundang Medical Center (latitude, 37.4°N) from August 2010 to July 2011. The study period was set to 1 year to eliminate bias due to seasonal variation. Subjects were investigated for the type of nursing, height, and weight. Additionally, complete blood count (CBC), iron, total iron binding capacity (TIBC), ferritin, calcium (Ca), phosphate (P), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and 25-(OH)D tests were performed.

Subjects were classified into IDA, ID, and normal groups according to the degree of iron. IDA was defined as Hb ≤11 g/dL and ferritin ≤12 ng/mL. Subjects with an inaccurate ferritin result due to inflammation were checked for low mean corpuscular volume (MCV) (≤70 fL) and reduced iron binding capacity (≤15%), and were included in the IDA group. ID was defined as Hb >11 g/dL and ferritin ≤12 ng/mL [

2,

15,

16]. Ferritin levels were measured by chemiluminescence immunoassay. VDD was defined as 25(OH)D ≤20 ng/mL, vitamin D insufficiency (VDI) as 25(OH)D of 20-30 ng/mL, and normal (vitamin D sufficiency [VDS]) as 25(OH)D >30 ng/mL [

13,

17].

We investigated the Pearson's correlations between the hematologic parameters (Hb, ferritin, and iron) and 25(OH)D levels. To evaluate the odds ratio between iron-deficient and vitamin D-deficient/-insufficient subjects, the IDA and ID groups as well as the VDD and VDI groups were combined into 2 separate groups for further analysis.

Using surveys, we obtained information about breastfeeding and weaning, birth-related history and family history, the mother's anemia-related history, and whether multivitamins were taken during the previous 12 months. To uncover the association between breastfeeding and iron and vitamin D deficiencies, we compared the breastfeeding proportion in each group. To test the seasonal effect on these deficiencies, subjects were divided into 2 groups, winter/spring (December to May) and summer/fall (June to November), according to the date of the test. Additionally, we compared the differences between the groups to determine the degree of VDD. Several factors (iron, breastfeeding, gender, age, and season) known to influence vitamin D levels were evaluated using multiple regression analysis.

In this study, the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; version 12.0) was used for statistical analysis. P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Go to :

RESULTS

Subject characteristics according to iron status

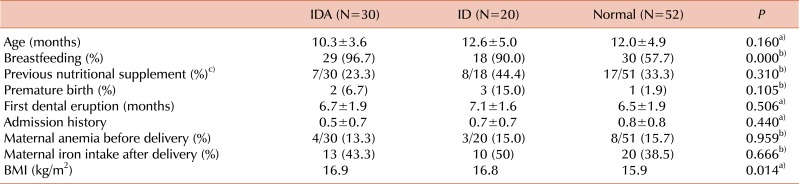

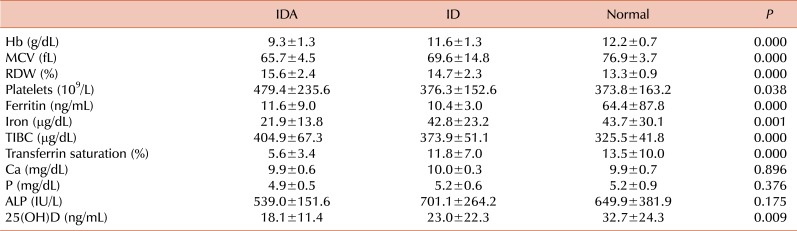

The breastfeeding ratio of the IDA and ID groups was higher than that of the normal group (

P <0.05). There were no significant differences between the 3 groups in age, multivitamin intake, preterm birth, dental eruption, admission history, history of maternal anemia, and maternal iron supplementation during breastfeeding (

Table 1). Four mothers were taking multivitamins, all of whom were in the IDA group.

Table 1

Patient characteristics according to iron status.

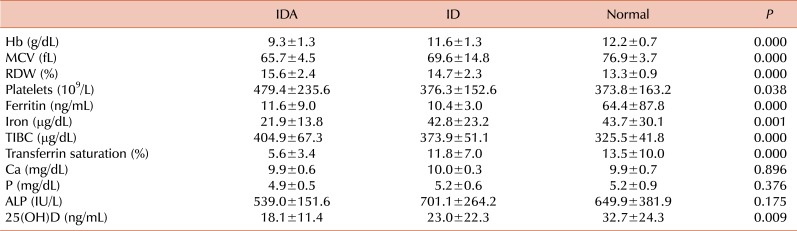

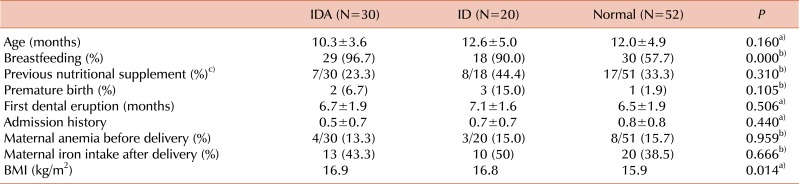

The Hb, MCV, ferritin, iron, and 25(OH)D levels of the IDA and ID groups were lower and the red cell distribution width (RDW), platelets, and TIBC were higher than those of the normal group (

P <0.05). No significant differences were observed between the iron-deficient and normal groups in Ca, P, and ALP levels (

Table 2).

Table 2

Comparison of hematologic and biochemical profiles according to iron status.

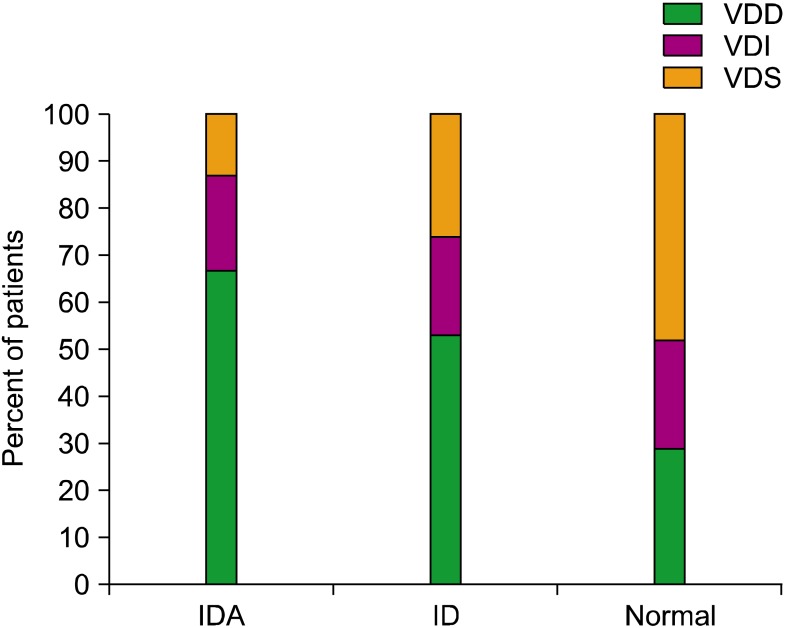

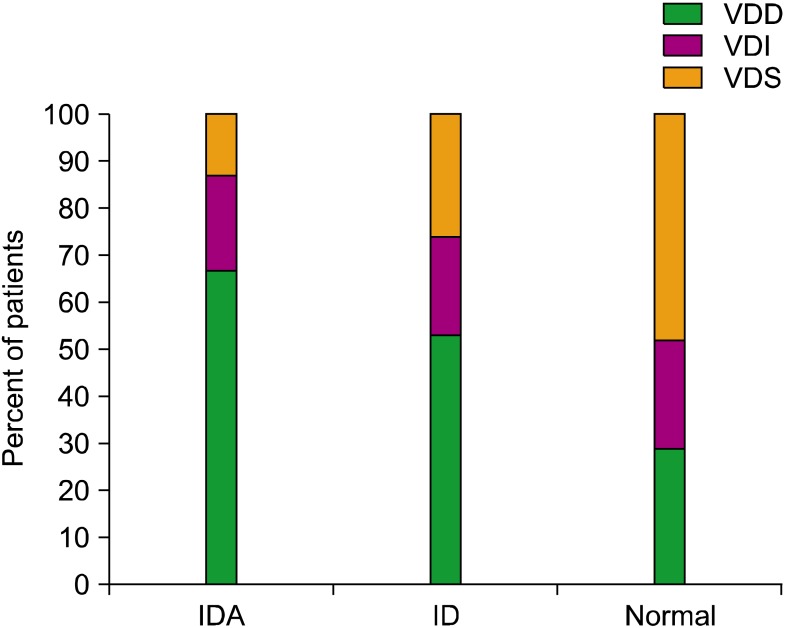

Comparison of vitamin D status according to ID status

The 25(OH)D levels were analyzed in all subjects except 1. In the IDA group (N=30), the number of subjects in the VDD and VDI groups was 20 (67%) and 6 (20%), respectively; those of the ID group (N=19) were 10 (53%) and 4 (21%), respectively. VDD was present in 15 (29%) and VDI was noted in 12 (23%) subjects in the normal group (N=52) (

Fig. 1). VDD was more prevalent in the IDA/ID group (

P =0.008). The Pearson's correlation was significant between the 25(OH)D and Hb levels (r=0.221,

P =0.026) but not ferritin or iron. The odds ratio calculated to determine the risk of VDD development (VDD+VDI) in patients with iron deficiency (IDA+ID) was 4.115, with a 95% confidence interval of 1.665-10.171.

| Fig. 1The ratio of vitamin D deficiency (VDD) among the iron deficiency anemia (IDA), iron deficiency (ID), and normal groups. Patients were divided into the VDD, vitamin D insufficiency (VDI), and vitamin D sufficiency (VDS) groups according to their 25-hydroxy-vitamin D concentrations.

|

Comparison of feeding type according to ID status

Seventy-seven (75%) subjects were breastfed; of these, 29 (97%) were in the IDA group, 18 (90%) were in the ID group, and 30 (58%) were in the normal group. The association between the presence of ID and breastfeeding was statistically significant (P =0.000).

Comparison of feeding type according to vitamin D deficiency status

Forty-three (96%) subjects in the VDD group (N=45), 12 (55%) in the VDI group (N=22), and 21 (62%) in the VDS group (N=34) were breastfed. Thus, the association between the presence of VDD and breastfeeding was statistically significant (P =0.000).

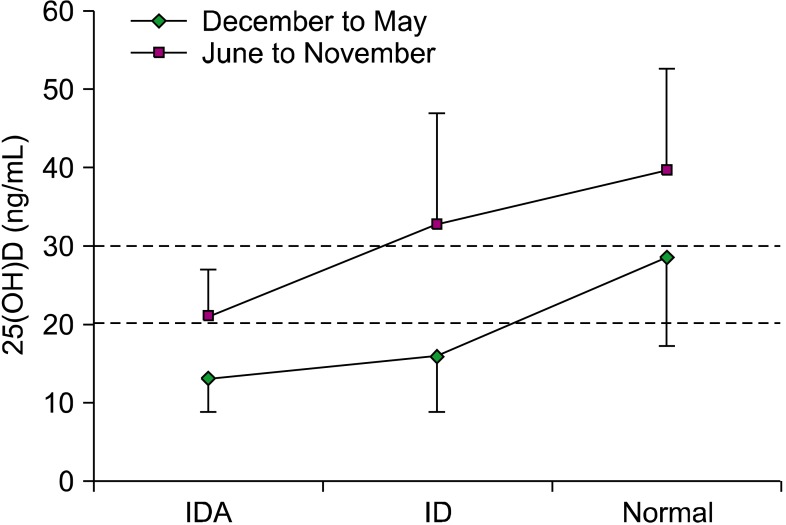

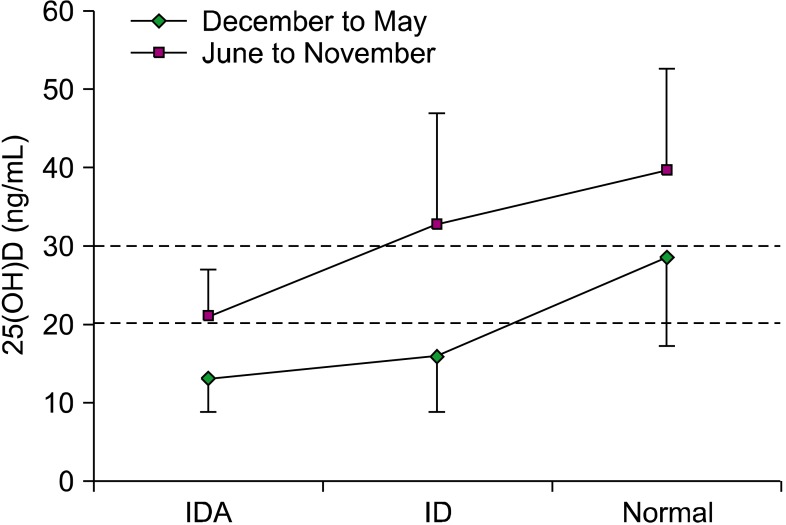

Comparison of vitamin D status according to the season

The seasons were divided into 2 groups and the 25(OH)D levels of each group were compared. The mean 25(OH)D values in the winter/spring (December to May) were lower than those in the summer/fall (June to November) in all 3 groups (2-way analysis of variance [ANOVA],

P =0.008). The mean 25(OH)D level of the IDA and ID groups was lower than 20 ng/mL in the winter/spring (

Fig. 2).

| Fig. 2Comparison of seasonal variation of 25(OH)D levels. All groups showed lower 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels in winter/spring (P=0.008). The average 25(OH)D concentration was subnormal in winter/spring in the normal group.

|

Comparison of BMI

The mean BMI of each group was calculated according to the degree of ID. This value was 16.9 kg/m2 in the IDA group (N=22), 16.8 kg/m2 in the ID group (N=14), and 15.9 kg/m2 in the normal group (N=34), with statistically significant differences between the groups (P =0.014). The mean BMI of each group was also calculated according to the degree of VD. This value was 16.7 kg/m2 in the VDD group (N=36), 16.3 kg/m2 in the VDI group (N=18), and 15.7 kg/m2 in the VDS group (N=15). The differences between the groups were not significant (P =0.078).

Factors associated with vitamin D levels

Multiple regression analysis of the factors potentially associated with vitamin D levels was performed, including serum iron level, breastfeeding, gender, age, and season. Among these factors, iron level, age, and season were statistically significant independent predictors of 25(OH)D levels (P = 0.005, 0.000, and 0.005, respectively).

Go to :

DISCUSSION

ID is an important issue, as IDA during infancy may cause long-lasting developmental disadvantages [

18]. Recently, the incidence of VDD cases and IDA patients with concurrent VDD has increased [

19-

22]. In this study, two-thirds of the IDA infants had concurrent VDD, with an odds ratio of 4.115. The correlations between the 25(OH)D, ferritin, and iron levels were not significant. This observation might be explained by the fact that ferritin levels increase during inflammation and iron levels have diurnal variation. In humans, there is no known study regarding the long-term adverse effects of concurrent ID and VDD. Katsumata et al. [

23] reported in a rat model that ID decreased the levels of 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, insulin-like growth factor-1, and osteocalcin concentrations, which resulted in decreased bone formation and bone resorption. As the final hydroxylation of vitamin D is dependent on iron, iron-deficient rats had lower concentrations of the active form of vitamin D. Diaz-Castro et al. [

24] also reported that bone metabolism was impaired despite normal 25(OH)D levels in iron-deficient rats. The main cause of decreased bone matrix formation was shown to be related to a decreased type I collagen amount. However, it is unclear whether severe IDA in humans would lead to the same phenomenon observed in animal studies. A study of Asian infants aged ≤2 years showed a significant association between coexisting ID and VDD [

19]. Similar findings were also observed in recent Korean studies revealing that a coexisting VDD frequently accompanies ID [

20,

21]. Therefore, VDD evaluation is needed for pediatric patients with ID and vice versa.

In this study, the breastfeeding ratios according to iron status were quite high in the IDA group (97%) compared with that in the normal group (58%). Although breast milk is the best nutritional source for infants, it can be a risk factor for ID [

2]. At-risk infants require careful intervention to identify those who are iron deficient even though they may be non-anemic.

The VDD group showed the highest breastfeeding ratio (96%) according to vitamin D status. There is an increased risk of VDD and rickets if infants are exclusively breastfed without being exposed to appropriate amounts of sunlight or vitamin D supplements, because breast milk vitamin D levels are insufficient for infants [

7]. According to Taylor et al. [

25], only a few breastfed infants take supplemental vitamin D. Many parents do not follow doctors' recommendations for vitamin D supplements because they think that breast milk contains all of the essential nutrients. In this study, only 32.3% of infants were taking any type of nutritional supplement, although the vitamin D and iron concentrations remained insufficient. According to the clinical guidelines from the Endocrine Society, 2,000 IU/day of vitamin D for 6 weeks is recommended for infants with VDD [

26]. After 6 weeks, the dosage should be decreased to 600-800 IU/day. Nevertheless, additional research is needed to reach a consensus on the appropriate dose and duration.

In this study, the seasonal comparison of vitamin D levels revealed that the average 25(OH)D level was lower in the winter/spring, which supported previous studies [

8,

9,

28]. This finding implies the importance of sunlight exposure and the need for increased supply of vitamin D, especially during the winter/spring seasons. Specker [

27] reported that if clothed breastfed infants are exposed to sunlight for 2 hours per week, serum 25(OH)D levels will increase by approximately 11 ng/mL. However, the precise amount of sunlight exposure needed to maintain normal levels of vitamin D is unknown. This can be explained by the fact that the amount of sunlight exposure can be affected by many factors such as clothing, race, skin color, sunscreen use, weather, latitude of residence, time of day, and air pollution. In addition, we cannot overlook the risk of developing malignant melanoma in adulthood due to childhood sunlight exposure. Thus, the American Academy of Pediatrics guideline recommends that infants aged <6 months should avoid direct exposure to sunlight [

28]. The body's need for vitamin D differs according to age, gender, pregnancy, and lactation status [

26]. Therefore, clinicians should strive to find the optimal dose and duration of vitamin D supplementation for each infant.

Generally, longer breastfeeding duration is associated with slower growth and lower BMI in the first year of life [

29]. In the present study, most of the infants in the IDA and ID groups were exclusively breastfed. When comparing the BMI of each group according to iron status, the average BMI values were significantly higher in the IDA and ID groups than that in the normal group. The comparison of the BMI of each group according to vitamin D levels showed a trend toward a higher BMI value in VDD subjects, albeit without statistical significance. Only two-thirds of the subjects were analyzed due to missing data; therefore, it might be difficult to draw a firm conclusion. The finding that the BMI of the iron-deficient infants was relatively high implies several things. A large body size does not necessarily mean that the person is not anemic; in contrast, it can be speculated that faster growth, without an appropriate iron supply, might result in anemia. Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin that also accumulates in adipose tissue [

30]. Therefore, a high BMI may indicate more adipose tissue with more vitamin D accumulation, although it is difficult to confirm this assertion based on the current study.

Known risk factors associated with VDD include gender (female), age (child or elderly), season (winter), lack of sunlight exposure, residence (high latitude), ethnicity (dark skin), clothing (clothing with low exposure), obesity, low socioeconomic status, and malnutrition [

8]. Malnutrition and protein deficiency can lead to VDD by decreasing the concentration of vitamin D-binding proteins in the blood [

8]. In this study, iron level, age, and season were the most significant factors that affected vitamin D levels. This result was also consistent with previous studies. Gender and the form of nursing did not show statistically significant associations with vitamin D levels, which can be attributed to the fact that this study is not a population-based study; hence, a larger study is needed.

There are limitations in this study, as it does not represent the general population and might be subject to selection bias. In addition, the number of subjects in the ID group was relatively small; therefore, the data are not sufficient to make an accurate comparison between the groups. Given the findings of other studies, the ID ratio is expected to increase significantly if the subjects include all infants aged <24 months. BMI data were missing from one-third of participants, which negatively affected the statistical significance. For further analysis, more accurate measurements of the anthropometric data and body fat composition might be needed. Vitamin D-related parameters such as parathyroid hormone, sunlight exposure, and dietary vitamin D assessment may add more clinical information needed to understand the consequences of VDD. Since there has been no research to date regarding concurrent ID and VDD, further studies are needed.

To provide the best nutrition for infants, breastfeeding is still recommended. There is a need to educate the public and those who are exclusively breastfeeding (even if the infant is asymptomatic) about the need for vitamin D supplements. Iron-deficient infants are more prone to VDD. The potential adverse effect of concurrent deficiencies is not yet known. Therefore, every child with IDA should also be evaluated for VDD. Lastly, educational efforts are needed to increase compliance with iron and vitamin D supplementation guidelines.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download