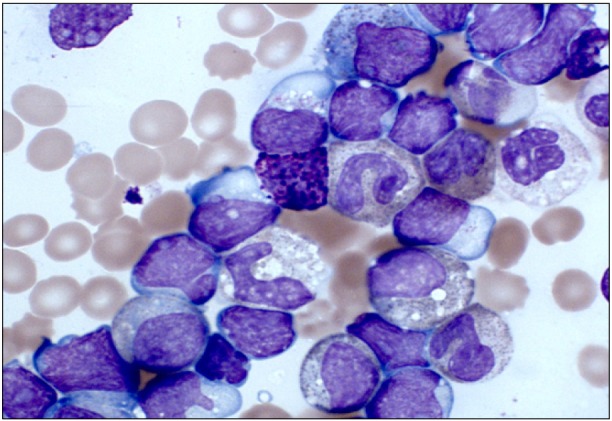

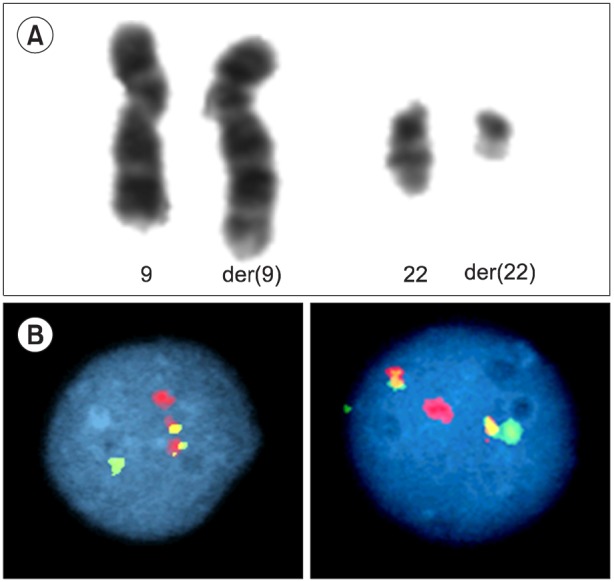

TO THE EDITOR: Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) is a rare hematological malignancy accounting for less than 3% of pediatric and adolescent leukemias, with an annual incidence of approximately 1 per million children and young people aged <20 years [1]. The natural history and biology of pediatric CML is similar to those of adult CML and follows a tri-phasic pattern. Approximately 95% of children present with chronic phase CML (CML-CP) and the remainder present in the accelerated phase CML (CML-AP) or in blast crisis (CML-BC) [2]. CML-BC is defined by >20% blasts in the marrow or the presence of extra-medullary blast proliferation [3, 4]. Blast transformation of CML is lymphoid in 30% of cases and myeloid in the remaining 70%. We report the case of a 10-year-old boy who presented with a 6-week history of weight loss and left-sided upper abdominal pain. On examination, he was found to have substantial splenomegaly extending into the right iliac fossa. His full blood count showed a hemoglobin level of 6.6 g/dL, a platelet count of 148×109/L, and a total white cell count of 575×109/L. A differential count showed the following: blasts, 30%; promyelocytes, 6%; myelocytes, 24%; metamyelocytes, 11%; neutrophils, 7%; eosinophils, 9%; basophils, 3%; monocytes, 1%; and lymphocytes, 10% (Fig. 1). Flow cytometry of the blast population showed that the blasts expressed CD19, cyCD79a, CD10, HLA-DR, CD34, and TdT surface antigens. Chromosome analysis showed a t(9;22)(q34;q11) translocation consistent with a Philadelphia chromosome (Fig. 2A). Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) showed BCR-ABL1 fusion signals in 90% of the nuclei (Fig. 2B). A minor breakpoint cluster region (210 kDa) was confirmed using RT-PCR. In the absence of a documented CML-CP, distinguishing between lymphoid blast crisis of CML and a Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL can be difficult. A diagnosis of CML in B-cell lymphoid blast crisis rather than de novo precursor B-cell ALL was made because of the concurrent presence of basophilia, a predominance of metamyelocytes and myelocytes, and the p210 BCR-ABL transcript. The patient did not have any additional chromosomal anomalies associated with advanced phase CML and was negative for IgH rearrangement on FISH analysis.

The patient achieved a complete hematological response and a minor cytogenetic response following induction therapy comprising dexamethasone, vincristine, daunorubicin, asparaginase, and imatinib. Nonetheless, he subsequently died of idiopathic pneumonitis after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation.

The progression from CML-CP to CML-BC in the pre-tyrosine kinase era is well described, but CML-BC at presentation in children is extremely rare. The case reported here adds to the literature on the simultaneous presence of features of both lymphoblastic transformation and CML at presentation in the absence of cytogenetic clonal evolution. Further research into the biology of the aggressive phase of CML is required to develop novel targets to improve outcomes.

References

1. Ries LAG, Smith MA, Gurney JG, editors. Cancer incidence and survival among children and adolescents: United States SEER Program 1975-1995. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute;1999.

2. Millot F, Traore P, Guilhot J, et al. Clinical and biological features at diagnosis in 40 children with chronic myeloid leukemia. Pediatrics. 2005; 116:140–143. PMID: 15995044.

3. Vardiman JW, Harris NL, Brunning RD. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the myeloid neoplasms. Blood. 2002; 100:2292–2302. PMID: 12239137.

4. Andolina JR, Neudorf SM, Corey SJ. How I treat childhood CML. Blood. 2012; 119:1821–1830. PMID: 22210880.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download