Abstract

Background

Advances in the understanding of Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) show various functions of infiltrating immune cells and cytokines in relation to clinical outcomes. The expression of CD163 and c-Met has been suggested to have a role in lymphoid malignancy. Thus, we evaluated the expressions of CD163, c-Met, and serum free light chain (sFLC) in relation to the clinicopathological features of patients with advanced classical HL (cHL).

Methods

We assessed the expression of CD163 and c-Met in 34 patients with cHL through immunohistochemistry on the lymph node biopsy sections and the levels of pretreatment sFLC were estimated using ELISA.

Results

High CD163 expression correlated with increased age, B symptoms, International Prognostic Score (IPS) ≥3, mixed cellularity subtype, and low response to treatment. Further, high c-Met expression correlated with increased age at diagnosis, leukocytosis, B symptoms, and lower chance to achieve complete remission. The sFLC levels correlated with increased age at diagnosis, lymphopenia, IPS ≥3, B symptoms, and lower complete remission rates.

Conclusion

In advanced cHL, increased expression of CD163 and c-Met showed a significant association with adverse prognostic parameters and poor response to treatment. Pretreatment high sFLC level also correlated with poor risk factors, suggesting its use as a candidate prognostic marker. A comprehensive approach for prognostic markers might represent a step towards developing a tailored therapeutic approach for HL.

Although the treatment for Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) can be considered a successful paradigm of modern treatment strategies, approximately 20% of patients with advanced-stage HL still die following relapse or progressive disease. A similar proportion of patients are over-treated leading to treatment-related late sequelae including solid tumors and end-organ dysfunction [1, 2].

Lymphoma-associated macrophages have been suggested to play a prognostic role in several different lympho-proliferative entities, including classical HL (cHL). Gene expression profiling data showed a correlation between up-regulation of genes related to intra-tumor macrophage infiltration and poor response to treatment, suggesting an underlying tumor-promoting role for these cells [3].

CD68, the most commonly used macrophage marker, is widely synthesized by a variety of normal and neoplastic cells, and it is therefore non-specific for the monocyte/macrophage lineage [4]. CD163 appears to be involved in anti-inflammatory functions predominantly associated with M2 macrophages, which promote tumor cell growth and metastasis, unlike M1 macrophages that kill tumor cells [5]. Unlike CD68, CD163 staining pattern is reported to show a cleaner background with less non-specific staining of Hodgkin's Reed-Sternberg (RS) cells and other inflammatory elements [6].

CD163 is a glycoprotein belonging to the scavenger receptor cysteine-rich superfamily [7]. It is controlled by various inflammatory mediators, such as interferon γ, interleukins 6, interleukin 10, and glucocorticoids [8].

The MET proto-oncogene located on the 7q31 locus encodes the receptor tyrosine kinase MET and is also known as the hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) receptor [9]. The binding of HGF to its receptor MET results in the phosphorylation of the tyrosine at the C-terminus of the receptor, leading to its activation and triggering downstream signaling [10]. This signaling pathway is involved in cellular proliferation, survival, and migration. [11] Furthermore, c-Met has been shown to have a prognostic significance in numerous malignancies including Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma [12].

The serum free light chains (sFLC) are kappa (k) and lambda (λ) light chains, which are produced by monoclonal and/or polyclonal B-cell populations [13]. The diagnostic and prognostic values of elevated sFLC levels are established in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, multiple myeloma, solitary plasmacytoma, and AL-amyloidosis [14].

sFLC abnormalities can occur in different ways: monoclonal elevated sFLC (elevated κ and/or λ with abnormal FLC ratio), polyclonal elevated sFLC (elevated κ and/or λ with normal sFLC ratio), and ratio-only sFLC abnormality (normal range κ and λ with abnormal sFLC ratio). The polyclonal increases in sFLCs are not associated with an abnormal sFLC ratio and may be indicative of renal dysfunction [15], older age [16], autoimmune disease [17], and chronic inflammation [18].

In the current study, we used immunohistological staining to assess the CD163 and c-Met expression in lymph node biopsy sections from newly diagnosed cases of advanced cHL, in addition to estimation of pretreatment sFLC levels, and determined their correlation with the clinicopathological features and the response to treatment.

In the present work, we studied 34 newly diagnosed patients with advanced cHL (stages from IIB to IV on Ann Arbor scale), who presented to the Hematology Department, Medical Research Institute, Alexandria University and Mostafa Kamel Military Hospital, Alexandria. Patients were diagnosed according to the results of the routine morphological and immunohistochemical examination of lymph node biopsy materials. The histopathological classification was based on the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria [19].

Patients were staged according to the Ann Arbor staging system [20]. Staging evaluation for each patient involved a physical examination; CT scans of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis, bilateral bone marrow aspiration, and trephine biopsy. Laboratory evaluation included complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and liver and kidney function tests. Presence or absence of B symptoms and bulky disease were reported. The patients were scored on the basis of the International Prognostic Score (IPS), which is based on age, gender, stage, and presence of hypoalbuminemia, lymphopenia, and leukocytosis [21].

Patients were treated with 6 cycles of adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD), which was complemented by radiation therapy in patients with bulky disease or localized residual masses. Treatment response was assessed using standardized guidelines [22].

Complete remission (CR) was defined as disappearance of all clinical evidence of disease and normalization of all laboratory values and radiographic results lasting for at least 4 weeks. Partial response (PR) was defined as a reduction of 50% or more in the sum of the products of the cross-sectional diameters of all known lesions lasting for at least 4 weeks [23].

Paraffin sections of the lymph nodes were stained according to the manufacturer's instructions using monoclonal antibodies against CD163 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Kalamazoo Michigan) and c-Met (Santa Cruz biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California). Staining was performed using EconoTek HRP anti-polyvalent (DAB) kit (Scytek laboratories, Logan, Utah). The slides were counterstained with hematoxylin and covered using a coverslip. The cut-off value for CD163 was 20%, whereas that for c-Met was 30%. These cut-off points for CD163 and c-Met were adopted based on the studies by Yoon et al. [24] and Xu et al. [11], respectively.

The slides were evaluated by 2 hematologists. CD163 was assessed on the basis of a membranous staining pattern, while the c-Met immunoreactivity was assessed on the basis of both membranous and cytoplasmic staining patterns.

Frozen pretreatment serum samples with normal renal function were assayed to detect κ and λ light chains by using human immunoglobulin FLC κ and λ ELISA (Biovendor Research and diagnostic products, Candler, North Carolina, USA).

The assay separately measures κ FLCs (normal range, 0.225-3.45 mg/dL) and λ FLCs (normal range, 0.45-5.42 mg/dL). In addition, the assay provides the FLC ratio (normal range, 0.23-1.85). Elevated FLC was defined as the κ or λ concentrations above the normal range.

Data was analyzed using the SPSS software package version 20.0. Qualitative data were described using number and percentage. Comparison between different groups regarding categorical variables was tested using the chi-square test. When more than 20% of the cells had expected counts less than 5, correction for chi-square was conducted using Fisher's exact test or Monte Carlo correction. The distributions of quantitative variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and D'Agostino test; in addition, histogram and QQ plot were used for the vision test. If the data displayed normal distribution, parametric tests were applied. If the data displayed non-normal distribution, non-parametric tests were used. Quantitative data were described using mean and standard deviation for normally distributed data. Non-normal distributed data was expressed using median, minimum and maximum range, and Mann-Whitney Test (used to analyze 2 independent populations). Significance test results are quoted as two-tailed probabilities. Significance of the obtained results was judged at the 5% level.

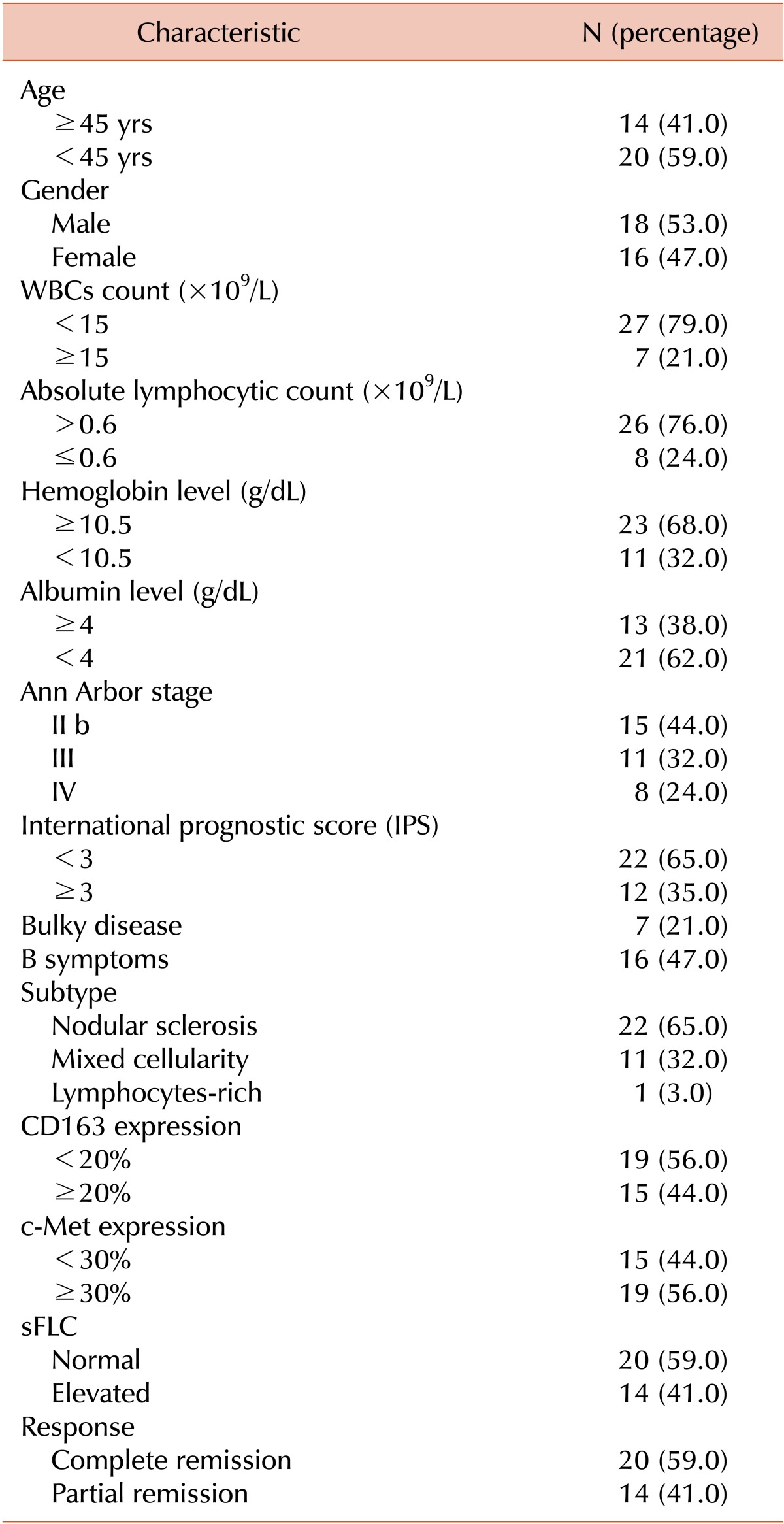

The main clinical and laboratory features of the study cohort at presentation are summarized in Table 1. The median age of the subjects was 30 years (range, 15-62 yrs). The male to female ratio was 1:1 with 18 males and 16 females. Sixteen patients (47%) exhibited B-symptoms and 7 patients (21%) presented with bulky disease. Stage II b was found in 15 (44%) out of the 34 patients, whereas 32% of patients were in stage III and 24% of patients were in stage IV. IPS was more than or equal to 3 in 12 patients (35%). The majority of the patients had histological features consistent with the nodular sclerosis subtype, approximately one-third of the patients had mixed cellularity, whereas only 1 patient had the lymphocyte-rich subtype.

The white blood cells count was ≥15×109/L in 21% of patients, and the absolute lymphocytic count was ≤0.6×109/L in 24% of patients. The hemoglobin level was less than 10.5 g/dL in 11 patients (32%) and 62% of patients had serum albumin levels less than 4 g/dL. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was higher than 40 mm/h in 60% of the patients. Marrow involvement was detected in 6 patients (18%). Following 6 cycles of ABVD therapy, 20 (59%) out of the 34 patients showed CR, whereas 14 patients (41%) showed PR (Table 1).

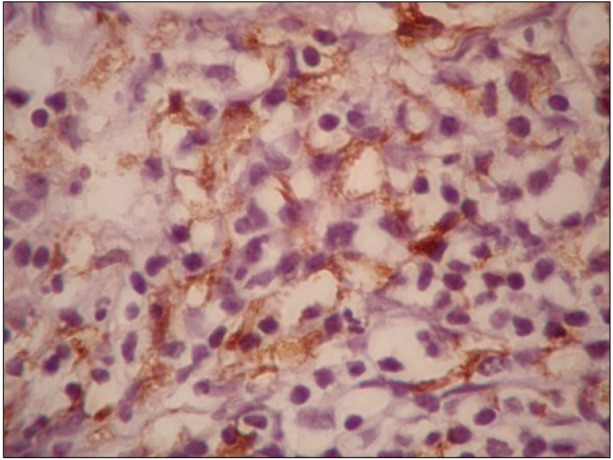

CD163 expression varied widely from 5% to 85% with a median of 15%. The expression of CD163 was categorized into 2 groups based on the 20% cut-off. Fifteen patients (44%) had CD163 expression of ≥20%. The pattern of macrophage infiltration was membranous (Fig. 1). The expression of CD163 was higher in mixed cellularity cases than in nodular sclerosis cases (P=0.006).

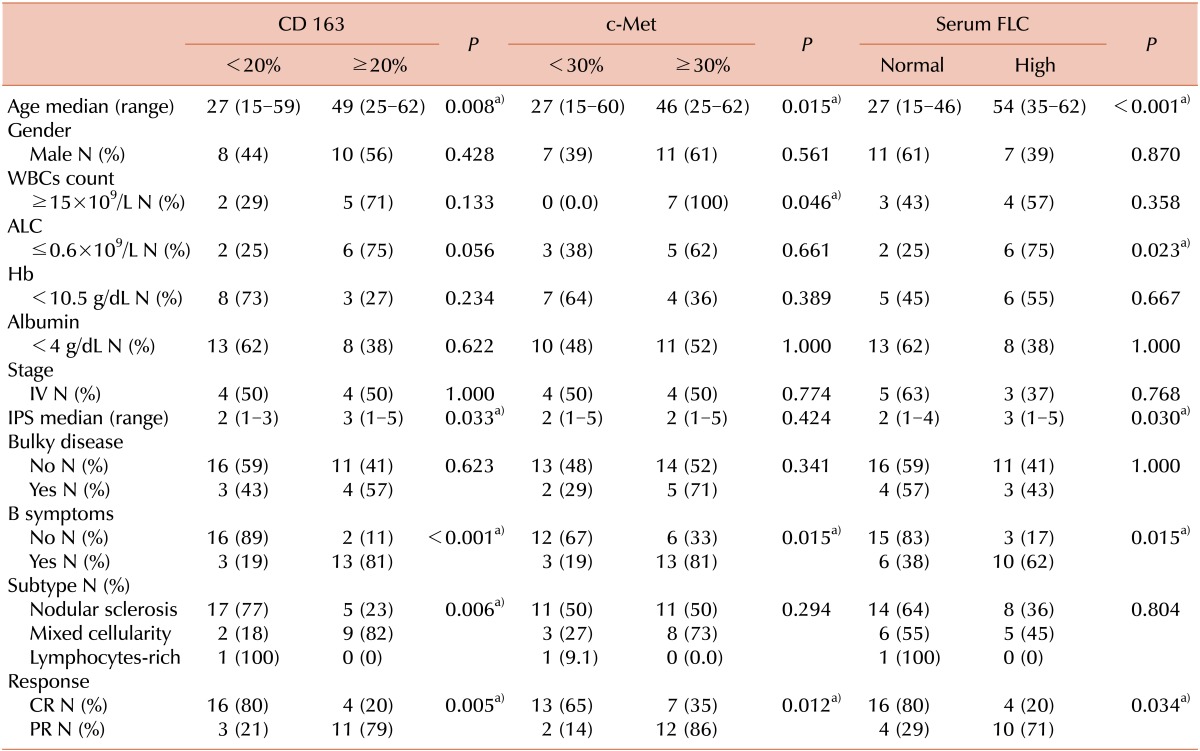

Correlations between CD163 expression and the clinicopathological features are shown in Table 2. High CD163 expression was associated with increased age (P=0.008), presence of B symptoms (P<0.001), IPS ≥3 (P=0.033), and lower CR rates (P=0.005).

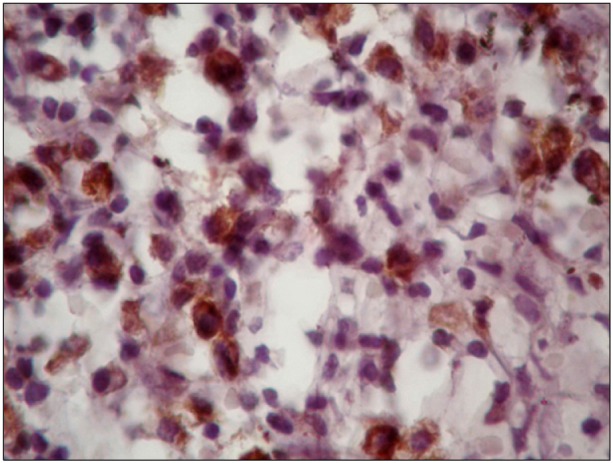

c-Met expression was 15-90% with a median of 35% (Fig. 2). c-Met was expressed in more than 30% of the tumor cells in 19 (56%) of the 34 patients. High expression of c-Met was associated with increased age (P=0.015), leukocytosis (P=0.046), presence of B symptoms (P=0.015), and lower CR rates (P=0.012), but was not associated with gender, histological subtype, or other known clinical prognostic factors such as bulky disease and IPS ≥3 (Table 2).

Median κ and λ FLC levels were 3 mg/dL (range, 1-9 mg/dL) and 2.2 mg/dL (range, 0.6-9 mg/dL), respectively. In 14 patients (41%), serum κ and/or λ FLC levels were elevated. This elevation was associated with increased age (P<0.001), lymphopenia (P=0.023), IPS ≥3 (P=0.03), presence of B-symptoms (P=0.015), and lower CR rates (P= 0.034), but not with other risk factors such as gender, leukocytosis, stage, bulky disease, subtype, and albumin levels (Table 2).

The tumor microenvironment is an important factor in the development and progression of cancer. Recent evidence suggests that the cellular composition of the tumor microenvironment can significantly modify the clinical outcome in hematologic malignancies, particularly in follicular lymphoma and cHL [25].

Tumor-associated macrophages are now accepted to play major roles inflammation and cancer through a number of functions (e.g., promotion of tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis, incessant matrix turnover, repression of adaptive immunity), which ultimately have significant impact on the disease progression [26].

In the present study, tumor-associated macrophages comprised 20% or more of the HL tissue, as per CD163 positivity, in 44% of our patients, and this was associated with older age at presentation, IPS ≥3, presence of B-symptoms, mixed cellularity subtype, and lower CR rates. On the other hand, a recent study by Azambuja et al. found no association between clinical characteristics and CD163 expression [27]. However, in concordance with our work, several published researches noted the inferior prognosis pertained with cases having increased tumor-associated macrophages.

Steidl et al. reported that the increased number of tumor-associated macrophages as per immunohistochemical positivity for CD68 was correlated with inferior outcome in cHL patients [28]. Two recent studies reported similar results. Tan et al. in a multicenter study stated that increased CD163 expression was significantly associated with increased age, mixed cellularity subtype, inferior failure-free survival, and overall survival in locally extensive and advanced-stage cHL [29]. Yoon et al. reported the association between high CD163 indices (≥20%) on one side and older age, male gender, presence of B symptoms, higher IPS (≥4), lower CR rates, and shorter duration of CR on the other side in cHL patients of any stage [24]. Kamper et al. [30] found that in cHL, a high number of intratumoral CD163+ monocytes/macrophages correlates with adverse outcome and clinical parameters reflecting underlying aggressive disease biology.

Lymphoid malignancies such as multiple myeloma and several B cell lymphomas were found to express c-Met, suggesting that c-Met is involved in the pathogenesis of these diseases [31]. We reported high c-Met expression (positivity in ≥30% of cells in HL tissue) in 56% of our patients, and the c-Met levels are associated with older age at diagnosis, leukocytosis (WBC >15×109/L), presence of B symptoms, and lower chance of CR. Teofili et al. [32] found similar association, and they hypothesized that HGF/c-Met interaction stimulates cytokine release by c-Met-positive RS cells, leading to some of the disease characteristics, namely, the B symptoms. Moreover, c-Met could also have an anti-apoptotic role due to its association with the anti-apoptotic protein BAG-1 and its functional partner Bcl-2 [33].

On the other hand, Xu et al. [11] reported that the expression of c-Met in tumor cells in patients with cHL strongly correlated with higher progression-free survival, whereas lack of c-Met expression was correlated with lower progression-free survival in the combined cohort. Notably, the immunohistochemical reporting of c-Met positivity was limited to RS cells in the study of Xu et al. [11], whereas in our study it refers to the HL tissue as a whole. We selected this way of evaluation, because it is impractical to limit the immunohistochemical evaluation to RS cells, which occur infrequently. Moreover, atypical forms of these malignant cells are present in certain subtypes of HL. Furthermore, in the study of Xu et al. [11], the reactive cells in HL tissue also reacted to c-Met. Finally, bidirectional cross-talk between the malignant cells and the reactive cells in the HL tissue is well known; thus, it is not justified to ignore the role of the reactive cells in the tumor behavior. Consequently, this difference in the reporting can be expected to explain the discordant results.

Nevertheless, recent studies by Scott et al. [34] and Steidl et al. [35] contradict this claim. These 2 groups recently published their work on the correlation between the gene expression profiling and prognosis in cHL. Scott et al. [34] conducted their research on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded biopsies containing HL tissue, whereas Steidl et al. [35] used microdissected Hodgkin RS cells, thereby restricting the sample to the malignant cells. The observed effect of the profiling signature retained its significance in both studies despite the difference in the studied samples.

Moreover, contradicting results about the prognostic significance of c-Met have been reported in multiple studies on different tumors. Moreover, a favorable prognostic impact of c-Met expression has been shown in the small-scale study on breast cancer of Nakopoulou et al. [36] and in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by Uddin et al. [37]. However, studies by Kawano et al. [12] and Lengyel et al. [38] showed opposite effects for both types of tumors.

Lymphoid malignancies often have a polyclonal B-cell infiltrate that can secrete immunoglobulins [39]. In the present study, 10 patients (40%) had elevated sFLC level, and the elevation was polyclonal. Elevated sFLC levels may reflect increased polyclonal B cell activity in cHL microenvironment. High sFLC levels correlated with increased age at diagnosis, lymphopenia (<0.6×109/L), unfavorable IPS (≥3), presence of B symptoms, and lower CR rates, but not with other risk factors such as sex, leukocytosis, stage, bulky disease, subtype, and serum albumin level.

In concordance with our results, Thompson et al. reported elevated sFLC in 30% of their cohort of cHL patients. sFLC elevation was significantly associated with age (>45 yrs) at diagnosis, advanced stage, presence of B symptoms, elevated erythrocytes sedimentation rate, and unfavorable IPS. There was no association of FLC elevation with lymphopenia or bulky disease [39].

On the other hand, Rosaria et al. [40] stated that high sFLC levels were correlated with lymphopenia, leukocytosis (WBC >15×109/L), elevated erythrocytes sedimentation rate (>50 mm/h), and unfavorable IPS (≥3), but not with stage, presence of B symptoms, bulky and extra nodal disease, serum LDH level, serum albumin level, and response rate.

Moreover, Rosaria et al. [41] reported that combining sFLC and Interim 2-[18F] Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography can identify poor risk HL patients, who may benefit from upfront treatment escalation or early salvage.

In agreement with our results regarding response to treatment, Ogura et al. [42] stated that CR rate after ABVD therapy was 58.2% for III or IV, but after radiation therapy, CR rate increased to 78.5%.

In summary, in advanced cHL, increased tumor-associated macrophage levels correlated with adverse prognostic parameters and poor response to treatment, reflecting underlying aggressive disease. Therefore, it might be a reliable marker to assess prognosis. While c-Met expression correlated with some bad prognostic parameters and affected the response to treatment, published reports presented contradicting results on c-Met expression. This invites researchers to conduct further work to validate the importance of c-Met expression in cHL. Pretreatment high sFLC level correlated with poor risk factors, suggesting its use as a candidate prognostic marker. A comprehensive approach to define prognostic markers reflecting diverse pathophysiologic concerns might therefore represent a step towards developing a tailored therapeutic approach best-suiting each patient's needs.

Notes

References

1. Aleman BM, van den Belt-Dusebout AW, Klokman WJ, Van't Veer MB, Bartelink H, van Leeuwen FE. Long-term cause-specific mortality of patients treated for Hodgkin's disease. J Clin Oncol. 2003; 21:3431–3439. PMID: 12885835.

2. van Leeuwen FE, Klokman WJ, Veer MB, et al. Long-term risk of second malignancy in survivors of Hodgkin's disease treated during adolescence or young adulthood. J Clin Oncol. 2000; 18:487–497. PMID: 10653864.

3. Sánchez-Aguilera A, Montalbán C, de la Cueva P, et al. Tumor microenvironment and mitotic checkpoint are key factors in the outcome of classic Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2006; 108:662–668. PMID: 16551964.

4. Lau SK, Chu PG, Weiss LM. CD163: a specific marker of macrophages in paraffin-embedded tissue samples. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004; 122:794–801. PMID: 15491976.

5. Jensen TO, Schmidt H, Møller HJ, et al. Macrophage markers in serum and tumor have prognostic impact in American Joint Committee on Cancer stage I/II melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009; 27:3330–3337. PMID: 19528371.

6. Harris JA, Jain S, Ren Q, Zarineh A, Liu C, Ibrahim S. CD163 versus CD68 in tumor associated macrophages of classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Diagn Pathol. 2012; 7:12. PMID: 22289504.

7. Schaer DJ, Boretti FS, Hongegger A, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of the mouse CD163 homologue, a highly glucocorticoid-inducible member of the scavenger receptor cysteine-rich family. Immunogenetics. 2001; 53:170–177. PMID: 11345593.

8. Schaer DJ, Boretti FS, Schoedon G, Schaffner A. Induction of the CD163-dependent haemoglobin uptake by macrophages as a novel anti-inflammatory action of glucocorticoids. Br J Haematol. 2002; 119:239–243. PMID: 12358930.

9. Galland F, Stefanova M, Lafage M, Birnbaum D. Localization of the 5' end of the MCF2 oncogene to human chromosome 15q15-q23. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1992; 60:114–116. PMID: 1611909.

10. Furge KA, Zhang YW, Vande Woude GF. Met receptor tyrosine kinase: enhanced signaling through adapter proteins. Oncogene. 2000; 19:5582–5589. PMID: 11114738.

11. Xu C, Plattel W, van den Berg A, et al. Expression of the c-Met oncogene by tumor cells predicts a favorable outcome in classical Hodgkin's lymphoma. Haematologica. 2012; 97:572–578. PMID: 22180430.

12. Kawano R, Ohshima K, Karube K, et al. Prognostic significance of hepatocyte growth factor and c-MET expression in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2004; 127:305–307. PMID: 15491290.

13. Bradwell AR, Carr-Smith HD, Mead GP, et al. Highly sensitive, automated immunoassay for immunoglobulin free light chains in serum and urine. Clin Chem. 2001; 47:673–680. PMID: 11274017.

14. Dispenzieri A, Kyle R, Merlini G, et al. International Myeloma Working Group guidelines for serum-free light chain analysis in multiple myeloma and related disorders. Leukemia. 2009; 23:215–224. PMID: 19020545.

15. Hutchison CA, Harding S, Hewins P, et al. Quantitative assessment of serum and urinary polyclonal free light chains in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008; 3:1684–1690. PMID: 18945993.

16. Katzmann JA, Clark RJ, Abraham RS, et al. Serum reference intervals and diagnostic ranges for free kappa and free lambda immunoglobulin light chains: relative sensitivity for detection of monoclonal light chains. Clin Chem. 2002; 48:1437–1444. PMID: 12194920.

17. Gottenberg JE, Aucouturier F, Goetz J, et al. Serum immunoglobulin free light chain assessment in rheumatoid arthritis and primary Sjogren's syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007; 66:23–27. PMID: 16569685.

18. van der Heijden M, Kraneveld A, Redegeld F. Free immunoglobulin light chains as target in the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006; 533:319–326. PMID: 16455071.

19. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, editors. WHO Classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC;2008.

20. Carbone PP, Kaplan HS, Musshoff K, Smithers DW, Tubiana M. Report of the committee on Hodgkin's disease staging classification. Cancer Res. 1971; 31:1860–1861. PMID: 5121694.

21. Hasenclever D, Diehl V. A prognostic score for advanced Hodgkin's disease. International Prognostic Factors Project on Advanced Hodgkin's Disease. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339:1506–1514. PMID: 9819449.

22. Boleti E, Mead GM. ABVD for Hodgkin's lymphoma: full-dose chemotherapy without dose reductions or growth factors. Ann Oncol. 2007; 18:376–380. PMID: 17071938.

23. Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25:579–586. PMID: 17242396.

24. Yoon DH, Koh YW, Kang HJ, et al. CD68 and CD163 as prognostic factors for Korean patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. Eur J Haematol. 2012; 88:292–305. PMID: 22044760.

25. Hsi ED. Biologic features of Hodgkin lymphoma and the development of biologic prognostic factors in Hodgkin lymphoma: tumor and microenvironment. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008; 49:1668–1680. PMID: 18798102.

26. Talmadge JE, Donkor M, Scholar E. Inflammatory cell infiltration of tumors: Jekyll or Hyde. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007; 26:373–400. PMID: 17717638.

27. Azambuja D, Natkunam Y, Biasoli I, et al. Lack of association of tumor-associated macrophages with clinical outcome in patients with classical Hodgkin's lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2012; 23:736–742. PMID: 21602260.

28. Steidl C, Lee T, Shah SP, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages and survival in classic Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362:875–885. PMID: 20220182.

29. Tan KL, Scott DW, Hong F, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages predict inferior outcomes in classic Hodgkin lymphoma: a correlative study from the E2496 Intergroup trial. Blood. 2012; 120:3280–3287. PMID: 22948049.

30. Kamper P, Bendix K, Hamilton-Dutoit S, Honore B, d'Amore F. Tumor-infiltrating CD163-positive macrophages, clinicopathological parameters, and prognosis in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009; 27(Suppl):abst 8528.

31. Capello D, Gaidano G, Gallicchio M, et al. The tyrosine kinase receptor met and its ligand HGF are co-expressed and functionally active in HHV-8 positive primary effusion lymphoma. Leukemia. 2000; 14:285–291. PMID: 10673746.

32. Teofili L, Di Febo AL, Pierconti F, et al. Expression of the c-met proto-oncogene and its ligand, hepatocyte growth factor, in Hodgkin disease. Blood. 2001; 97:1063–1069. PMID: 11159538.

33. Bardelli A, Longati P, Albero D, et al. HGF receptor associates with the anti-apoptotic protein BAG-1 and prevents cell death. EMBO J. 1996; 15:6205–6212. PMID: 8947043.

34. Scott DW, Chan FC, Hong F, et al. Gene expression-based model using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded biopsies predicts overall survival in advanced-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31:692–700. PMID: 23182984.

35. Steidl C, Diepstra A, Lee T, et al. Gene expression profiling of microdissected Hodgkin Reed-Sternberg cells correlates with treatment outcome in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2012; 120:3530–3540. PMID: 22955918.

36. Nakopoulou L, Gakiopoulou H, Keramopoulos A, et al. c-met tyrosine kinase receptor expression is associated with abnormal beta-catenin expression and favourable prognostic factors in invasive breast carcinoma. Histopathology. 2000; 36:313–325. PMID: 10759945.

37. Uddin S, Hussain AR, Ahmed M, et al. Inhibition of c-MET is a potential therapeutic strategy for treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Lab Invest. 2010; 90:1346–1356. PMID: 20531293.

38. Lengyel E, Prechtel D, Resau JH, et al. C-Met overexpression in node-positive breast cancer identifies patients with poor clinical outcome independent of Her2/neu. Int J Cancer. 2005; 113:678–682. PMID: 15455388.

39. Thompson CA, Maurer MJ, Cerhan JR, et al. Elevated serum free light chains are associated with inferior event free and overall survival in Hodgkin lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2011; 86:998–1000. PMID: 22006790.

40. De Filippi R, Russo F, Iaccarino G, et al. Abnormally elevated levels of serum free-immunoglobulin light chains are frequently found in classic Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) and predict outcome of patients with early stage disease. Blood. 2009; 114(ASH Annual Meeting):abst 267.

41. De Filippi R, Morabito F, Corazzelli G, et al. Use of the cumulative amount of serum-free light chains (sFLC) at diagnosis and PET2 for the early identification of high risk of treatment failure in Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL). J Clin Oncol. 2012; 30(Suppl):abst 8083.

42. Ogura M, Itoh K, Kinoshita T, et al. Phase II study of ABVd therapy for newly diagnosed clinical stage II-IV Hodgkin lymphoma: Japan Clinical Oncology Group study (JCOG 9305). Int J Hematol. 2010; 92:713–724. PMID: 21076995.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download